Up until the late XIXth century, Macau was clearly divided into two fairly distinct quarters: the Christian quarter and the Chinese quarter.

The Christian quarter, with its Portuguese style houses and mansions, its gardens and Western fruit trees, spread through the centre and southwestern part of the peninsula. These houses tended to cluster round the old churches and convents in the quarter, which had been the old walled burgh. The constant clanging of bells, signalling the Ave Marias at dawn, to compline at nine in the evening, the rolling of the drumbeat and the soaring bugle calls from the garrison barracks endowed Macau with a character quite different from the other cities in the region "where the practical spirit of the British took precendence and where business absorbed any other facet of living". (1)

Dotted around outside of this area were the residences and stately homes of foreigners and rich Macanese, stretching in the south from Barra to Nilau (Penha) and in the north around Flora, Cacilhas, Solidão and D. Maria II. There were also beach houses at Areia Preta, where land had already been reclaimed from the sea. The few residences on Lappa had been abandoned in around 1764. (2)

The more important mansions on the peninsula were S. José (Manochai) Santa Sancha, Maria Filipa, Leitão (opposite the Parsee Cemetery) and the one belonging to the Canossan nuns (in Areia Preta). There were also the orchards of Mitra, Patane, Volong (until 1894), the Companhia, Bom Jesus, Mouros and Espírito Santo.

The Chinese quarter stretched round the Inner Harbour from the temple at Barra to the one at Lin-Fong. It edged it way into the Bazaar and the Rua da Alfândega, the S. Lázaro Market and out to Mong Ha Hill, taking in the three villages and the farming and fishing community on the northern outskirts.

Let us take a walk through the Chinese section of Macau, as it was one hundred years ago, led by four contemporary guides, Manuel de Castro Sampaio, the Brazilian Henrique C. R. Lisboa, the Count of Arnoso and Bento da França. We shall examine its inhabitants, their clothing, homes, food, habits and customs. (3) From the path we follow, we shall be able to see that in certain quarters such as Manduco, the lowland at the foot of Si-Shen (Persimmon) Hill, Travessa dos Diabinhos (now dos Anjos) and particularly in S. Lázaro and Sto. António, the Portuguese and Chinese communities lived together in harmony.

In order of decreasing size and importance, the ethnic groups which settled in Canton Province were as follows: the Han, the Lai (from Hainan Island), the O, the Mui or Meao (the biggest ethnic group in the north of Laos), the Yueh, the Wui, the Chong and a few Keng.

Members of all these groups can be found in Macau but the dominant group is the Han. These are the most representative of the Chinese who came down from the North and married with the Yueh (196 B. C.) and the Malayans on the coast during the later Han Dynasty (25-220 A. D.). They speak Cantonese, a language which is only oral. Before, the purest forms were spoken in the cities and towns in Canton and Sui-Hing but now that education has become available to all, pronunciation has been normalised in all the major cities, namely Canton, Fatshan, Macau and Hong Kong. (4)

To the foreigner, one of the most distinctive features of Macau was the manner in which the Chinese wore their hair. The Manchus demanded that the Chinese shaved their heads bare, leaving nothing but a line of hair from the crown of the head to the nape of their neck where they let the hair grow into a tail which was tied at the end with a piece of black silk to make it seem even longer. While they were working, labourers, servants and ferrywomen rolled their queue round their head, the ferrywomen covering it with a cloth.

Upper-class ladies pulled their hair back and then teased it up until it could sit like two handles over their ears. Then they pinned it with a silver or gold comb into what was called the "butterfly" style. Single women bound their hair into a plait which fell down their back unless they threw it over their right shoulder and buttoned it into their tunic.

Many of the rich Chinese in Macau were honorary mandarins who had taken refuge here after civil wars or had retired here. The same was the case in Kowloon, where public officials and officers from the Chinese army had gone after 1911. They wore long silk tunics with leggings of the same material, fine cotton socks and black silk shoes with a thick paper sole pointed at the toes. In winter they would pull a heavy padded cotton coat over their tunic to keep warm. Usually they were carried in sedan chairs when they went out. The sedans were sometimes quite luxurious, carried by means of two quince wood poles resting on the shoulders of either two or four coolies.

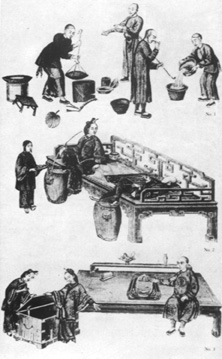

Chinese customs at Chinese New Year ("Illustrated London News", 14th April, 1860, published in

Hong Kong Illustrated Views and News 1840 1890).

Chinese customs at Chinese New Year ("Illustrated London News", 14th April, 1860, published in

Hong Kong Illustrated Views and News 1840 1890).

Distinguished ladies showed off their standing with "lost sleeve" tunics. They were easily recognisable by their superior quality of clothing, their use of cosmetics, jewellery - particularly jade.

Workers and shop owners wore nothing more than wide black cotton trousers, going unshod and bare-chested. Coolies used broad-rimmed straw hats and wore straw sandals with no socks.

Lower class women dressed in a short tunic blouse of black or blue cotton, with baggy trousers of the same cloth. Almost all of them went barefoot, but this custom is no longer to be found.

Parasols and umbrellas were made of oiled paper stretched over a bamboo frame and painted in bright colours such as can be seen in classical Japanese watercolours, but even by then, European style parasols were being introduced. (5)

The houses in the Chinese quarter were one or two stories high and lacking in light and ventilation. Wealthier homes all looked more or less alike with a high stone or brick wall surrounding them and three consecutive arches at the entrance made of carved stone or wood. Inside was a kind of lobby with another three arches at the far end opening into a patio where the reception rooms were to be found. The family rooms were located in various buildings, separated by square courtyards with miniature trees and a centrally located water tank. These were connected by corridors with moon gates. The living quarters for women were always located in the furthest corner.

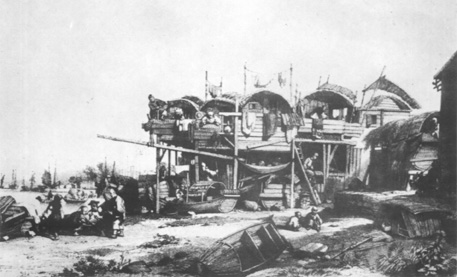

Poor people lived on the outskirts of the city in huts fashioned out of mud with straw roofs. In the marshes at Sankiu and Sa-kong, hovels rose out of the ground supported on stilts. Ferrywomen and their families from Fuchow were in the lowest stratum of society. They lived confined within boats anchored in the Inner Harbour or at Praia Grande in the company of their children, husbands (who could work in the city), dogs, hens and pigs.

The Bazaar was a maze of tortuous, narrow streets, many of which remain to this day. Here the houses were low and jammed together in a haphazard arrangement with a clutter of sticks, boards, clothes hanging out to dry, ropes and all kinds of tools arrayed in the doorways or stretched out over the street.

Fishermen's dwellings in Macau's Inner Harbour - Auguste Borget (1809-77) in La Chine et les Chinois, lithograph by Eugène Cicéri, Paris, ed. Goupil et Vibert).

Fishermen's dwellings in Macau's Inner Harbour - Auguste Borget (1809-77) in La Chine et les Chinois, lithograph by Eugène Cicéri, Paris, ed. Goupil et Vibert).

The extreme overcrowding in such a density of houses with windows facing only to the front, the narrow streets and chaotic cohabitation of men and animals, the combination of work and home which led to almost every ground floor being used for business, meant that the smells of musk, opium, varnish, oil and most of all, fish and dung, were overpowering in this area. (6).

"The furniture in the homes of the Chinese was quite different from what was used in XIXth century houses in Europe. Some of it was quite splendid, fashioned from magnificant woods, beautiful marbles with exquisite relief, carving and gilding, for the Chinese are experts in their workmanship." (7)

The butchers displayed huge chunks of meat and plucked fowl hanging from hooks. Tea was prepared under awnings out on the street, while food was cooked on stoves as is done in Portugal at the country fairs. Street vendors called out their wares of fruit and vegetables as crowds of Chinese thronged the streets.

Playing "Fan-tan" in a gambling den in Macau ("The Graphic, 17th May, 1873).

Playing "Fan-tan" in a gambling den in Macau ("The Graphic, 17th May, 1873).

Here and there, pawnbrokers establishments rose above the general outline of the houses. The famous Chung Volong pawnbrokers had no less than six floors. On the ground floor the employees received the goods. The five floors above were reached by means of a narrow staircase. They were not divided into rooms, but simply lined from ceiling to floor and wall to wall with parallel rows of magnificent wooden cupboards where the pawned goods were kept. Between the rows there was just enough room to allow access to the cupboards. These brokers were so well organized, that even people who did not need money stored the clothes they did not require each season there so as to keep them in good condition.

The colaus, or opium dens, had luxurious wide stairs with gilded mirrors above the steps. Some of them also served as guest houses and these establishments were particularly noted for the elegant parties thrown by the Chinese. A typical scene was one of the waiters shouting the names of the delicacies ordered down the stairs to the kitchens. One of these clubs was described in detail by the Count de Arnoso. (8).

Another feature of the Chinese quarter was the fan-tan houses. These gambling dens, decorated with lanterns were open all day until midnight. To avoid mixing with the commoners, the rich Chinese and Europeans went to an upper floor where they could gamble, seated around a balustrade opening onto the floor below. The bets were placed in baskets which were lowered and raised with a string. The fan-tan agent paid large sums of money in taxes to the government.

The Vae-Seng lottery was another vice in which the Chinese liked to indulge. Whenever there were government examinations in Peking and provincial examinations in Canton, each lottery ticket contained the surnames of twenty candidates. Each group of one thousand tickets made up a series and each series constituted a lottery with three numbers. The winner was the holder of the ticket with the highest number of surnames of successful candidates. Tickets cost half, one, two, three, five and ten patacas. Authorization to sell the tickets was given by the Chinese government and the Macau agent then paid a tax to the Portuguese government in Macau.

Moving from pleasure to industry, there was a variety of activity in the territory. There were several tea blenders who did excellent trade, one tobacco factory, one opium refiner, a cement factory in Ilha Verde and three silk spinners. Of the latter, the largest was Hao-Keng-Lun, which employed over four hundred women, providing them with an alternative to the miseries of prostitution.

Ma-Kok Temple, c.1863 - Edward Hildebrandt (pub. by Von Decker, coloured lithograph, 24.7 x 14.9 cm).

Fishing and salting, on the other hand, occupied at least ten thousand people towards the end of the last century in Macau. It was an increasingly profitable source of income.

One very interesting marginal trade that went on in those days was the export of "plaits cut from the corpses of the Chinese". These were exported to Europe where they were used in wig-making.

The daily eating routine of the Chinese in Macau one hundred years ago started off in the morning with dim-sum or yam-cha in the tea salons which still exist on the Rua Nova de El-Rei (now called Cinco de Outubro). Later on there were two full meals, one at around mid-day and the other at sixish. After the games of mah-jong, supper was served before retiring to bed.

The morning tea, which now includes coffee due to European influence, was a time for friends, relatives and business partners to come together in the noisy rooms crowded with customers. Employees would push round trollies carrying glutinous stuffed rice, prawn balls, meat balls and other delicacies served four in each little bamboo basket. This is one custom which has been preserved even to this day.

Above: Rua da Felicidade (or "Happiness Street", named after the density of "flower" houses located on this typical Chinese street).

Above: Macau residence by George Chinnery (sketch, 1827, 19.5 X 26 cm).

Similarly, the two main meals were composed of steamed rice with no salt, a main dish of meat or fish and vegetables, then fruit and soup at the end of the meal. The Chinese never drank cold water, nor did they eat the meat of farm animals such as cows, horses and buffalo. A special delicacy at these meals was, and still is thousand year eggs preserved in mud.

On holidays, there were dozens of different dishes, all of them generously sprinkled with rice wine. Particularly highly rated was sea cucumber, shark's fin, bird's nest and roast duck. The Chinese were also happy to taste certain Macanese dishes, especially the sweets such as "baji" (sweet Indianstyle rice), "ondi-ondi" (cakes stuffed with dark sugar), "camalenga" (grated pumpkin and candied sugar), and so on. (9).

The New Year celebrations, lasting for two weeks, the Ching Ming festival, the Dragon Boat Races, the porcelain cocks placed on the rooftops to ward off termites, the beggars, the visits to temples, the cricket fights, cockfights and many many other things have changed little since those days.

While people no longer wear queues nor walk barefoot, the elegant, long tunic which a Shanghai dressmaker brought up to date for women to wear has also disappeared, along with silken shoes and other Chinese fashions.

It was the Chinese quarter which was responsible for giving the distinctive colour and liveliness to the old city. Once the decline in the coolie trade began to have a noticeable effect on the prosperity of the city, the days when ladies such as the Baroness of Cercal could change their gowns three times in a single night became increasingly few and far between. The XIXth century was indeed a special time for Macau, caught between the fluctuating fortunes of, on the one hand, the massive Chinese empire and on the other, the rapidly developing colony of Hong Kong. The legacy which remains from those days can still be seen in corners of modern Macau, the Chinese quarter having laid aside its geographical limits to share now the whole of the city alongside the many other populations living and working here.

Sequence of drawings demonstrating the downward spiral caused by opium addiction: preparation of the drug for sale to owners of opium dens, Chinese smoking with his wife, selling personal possessions to support the habit and, finally, ruin ("Illustrated London News" 18th December, 1858, published in Hong Kong Illustrated).

NOTES

(1) Henrique C. R. Lisboa: A China e os Chins, Montevideo, 1888 (taken from Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, vol. IX, N° 3 & 4,1975, pp. 165-181).

(2) Benjamim Videira Pires in Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, vol. I, N° 4 & 5, 1967, pp. 331-2; Father Manuel Teixeira: Taipa e Coloane, DSEC, Macau, 1981, pp. 19-22. We know of at least ten Portuguese residences on Lappa which, along with the battery and shipyards on Wanchai and the two little islands opposite Barra, Bugio Grande and Pequeno, make fourteen properties; Also Austin Coates: A Macao Narrative, Heinemann, 1987, pp. 32-33; On small farms and orchards, see António Júlio Emerenciano Estácio: Dinámica das Zonas Verdes na Cidade de Macau, 1982, pp. 10-16; There is still a lot to be written on the exchange of flowers, plants and commodities between Europe and the Orient but for an introduction, see J. M. Braga: Hong Kong and Macau, a Record of Good Fellowship, Hong Kong, 1960. pp. 66-67.

(3) Manuel de Castro Sampaio: Os Chins de Macau, Hong Kong, 1867; Henrique C. R. Lisboa: ob. cit.; Conde de Arnoso: Jornadas pelo Mundo, 1896; Bento da França: Macau e os Seus Habitantes, Lisbon, 1897.

(4) Louis Aubazac: Dictionnaire Cantonais-Français, Hong Kong, 1912, p. IV.

(5) Bento da França: ob. cit., p.125.

(6)Idem., ob. cit., pp. 128-130; Henrique C. R. Lisboa: ob. cit., pp. 120-121.

(7) Bento da França: ob. cit., p. 130.

(8) Conde de Arnoso: ob. cit., pp. 130, 140, 142-3.

(9) Another interesting facet of this is the combination of Oriental and Portuguese sweets in Macau's cooking. Celestina de Melo and António Vicente Lopes have each left us one book and there are still Macanese ladies who could hopefully provide more information on the subject prior to 1999.

start p. 53

end p.