The fleets which the Chinese king has to guard these shores are one of their greatest marvels, because without being at war with anyone, they are just to show authority and good government. There is a superintendent, who they call Aitão• 1 on the nearby island of Lantao, • 2 who does nothing more than send ships to sea from a shipyard and arsenal fitted out with everything necessary, because there is such an abundance of wood on the island and the rest of the material is brought from other areas. The main ships are as high and long and efficient as naos3 and decked out4with several gilded rooms and lounges, partly by brush on the moulded borders, and what is not gilded has a transparent varnish like a mirror, inside and outside the ship. They work with great care, especially on the flagships and ships which will be sailed by famous people, including others of less importance, and they always bring more than two hundred and fifty in the fleet under the jurisdiction of this province of Guangdong• 5 up to the vicinity of Fujian, • 6 which is another district where they have other fleets for their own defence. The chief general is called a Chumpim• 7 and it is a post holding great power and authority, even though it is beneath the Tutão. • 8 They are always accompanied by a lot of sentries and a great display of shawms, flutes and their style of kettle drums, which are dissonant for our ears.

This entire pageant of ships is armed, but on close inspection, it is no more than smoke, as one would say, for [the ships] are very fragile, with [the Chinese] simply taking care of decorations and ostentation, being in reality of little threat, because they do not dare leave the coast by more than three leagues out to sea {with their vessels}. * They do no more than cruise up and down the coast in calm weather and on hardly feeling the wind they anchor, for everything to be absolutely safe and smooth for their flat bottomed ships. The artillery they use are some esmeris9 of iron and none of them with reinforcing circular metal braces, 10 with bad gunpowder; and they are not all [operational], using them more to shoot off flairs than to fight. They also have some badly made short arcquebuses, of a lot of ammunition and little firepower, which, in my opinion, any ordinary corselet11 would resist the more so they do not know how to shoot well. The rest of the weapons are pikes made from cane and other staffs, some of iron and others with points, short heavy cutlasses, and some metal helmets.

When they encounter some pirate, they usually surround him with a hundred ships, throwing a lot of sifted lime over the enemy on the windward side to blind them, and they succeed in overpowering them in the end, as there are so many. This is one of the best combat tactics they know. The pirates are normally Japanese or even seditious Chinese. If any ships from this fleet meet up with some little peace-seeking boat, be it from there, or Japanese or Portuguese, they steal it and burn it, killing the crew and throwing them into the sea so as not to leave any signs at all. They do this even if the said boat brings documents granting privileges and safe conducts from the Tutão, 12 but without his knowledge, or that of their general, for if he were to find out what had happened, they would be severely punished.

When I arrived in China, on board a fine, well armed frigate, some of the infinite number of ships who sail up and down the coast came up to identify us. However none of them bothered us, we even anchored together in Macao, where a high captain of the Guangdongnese guard boarded with an official document which he brought stuck onto a board, like a price list at an Inn, asking for my name to advise the Chinfu,• 13 who charged for the royal rights. I gave some reais for him and his soldiers, to get off on the right foot.

It is shameful to talk about the behaviour of these Chinese soldiers. There have already been some days when [the soldiers] have fought against other Chinese who had brought provisions from overland [from Macao], destroying them with blows. They complained to the mandarin who governed Macao, who took forty soldiers and then sent them to be whipped, and I saw them coming out crying like children. They are very vile people, unruly, rogues with little spirit and one need not be afraid of thousands of them. In the end, what militia could there be on land which has troops in such a state of disrepute, being the remainder {of the population} all slaves? Not a single one for certain. Our Indians from the Philippines are more courageous.

All the cities and small towns are surrounded by temporary fortifications of stone, being equally very watchful because of thieves, not only around the walls and gates, but also in the streets which they guard themselves by closing them off at night and by keeping sentinels. All the inhabitants of the neighbourhood are forced to serve as sentinels, being severely punished if they fall asleep or do not pay attention. However the walls have no geometrical proportions, nor timber frames, nor bunkers, nor ditches, nor artillery.

The Chinese cannot have any kind of weapon in their homes, with the exception of these miserable soldiers, but there are public storehouses, and ones belonging to the king, with a great quantity of lances, swords, halberds, [and] helmets which are kept in case they are needed. There are many horses, of the small kind, but only used by poor people for riding as the mandarins are usually transported in sedan chairs on their lackey's shoulders. These sedan chairs are highly gilded and covered over because of the sun and water. They do not use reins [on the horses] but just a halter. They ride with short stirrups14 but with little elegance. After all they have no mounted cavalry, even though they say they have big horses in the Beijing· province. The [Chinese] kings used to live in Nanjing • but they moved to Beijing because they had a border there with the Tartars, with whom they had been at war. 15

They consider the behaviour of the chincheus, 16as the most warlike, and a few years ago they revolted and elected a king. 17 However the Tutão of that province distracted them with such intelligent discourse that he managed to contain the situation, and later severely punished many of them, invoking the [Imperial] orders which forbade the Chinese to leave the kingdom by land or sea. Nevertheless, [the authorities] usually ignored the Chinese from Fujian in order to keep them quiet, allowing them to sail off and trade freely, except with the Japanese, who were public enemies. Thus they went to the Philippines, Java, Siam, Patane, Cambodia, Joor18 and Sumatra and other places, laden with silks, cotton cloth, crockery and many other goods from China [in exchange for which] they brought back silver, pepper, cloves [and] brasil. 19

The women are very beautiful, white like the Spanish with black hair and are naturally very honourable. They have the added grace of having small feet. This [custom] became obligatory to such an extent that daughters of nobility have a nerve cut in the soles of their feet at birth and have their feet bound so that they would not grow. This is why they walk so little and very slowly, not being as inclined to walk like our [women]. As recounted by Father [Fr. Matteo Ricci in his letter]20 the king has thirty-six wives, and when he wants to have companionship with one of them, he orders a written document to be taken down with witnesses, noting the day, month and year, in order to guarantee the faithfulness and continuity of the royal lineage, even though all the duties around the house are carried out by eunuchs. The compensation that is given to the {king's} wives is that when the king dies, they are put up for auction, not to be slaves, but so that the buyer can marry them. They are taken veiled and covered in order that no-one knows what their body is like, or whether they are young or old. [At this auction] they make huge bids, just as much for the quality [of the women] as for the fact that some of them take along a lot of jewels and money which they have received from the king, in such a way that they are worth far more than what the new husbands pay for them.

Among the other great vices, these Chinese are marked with the heinous [vice]21 which is not punishable among them, as all these mandarins have a lot of [men] around them to serve them, which they value highly, and just as they have liaisons with women, there are also liaisons with these miserable {creatures}.

[The Chinese] are captivated by music, about which they have many books and much talent, but [at the same time] it is very distinct from ours, as is sounds dissonant to us. They have thin, smooth paper which they make from cotton. Among them the use of the typographic press is very old and perhaps Europe had taken the invention from this land. 22

There are many silver mines in the hills surrounding Macao and all those islands in Guangdong have recognised silver veins. The king does not allow their exploration so that people do not forget agriculture and trade. And in one [mine] which the Chinese began working, they erected a fence and sent a garrison there, under a very trustworthy captain, so that the silver was not extracted from it. A lot of silver comes from overseas, as the account [of Fr. Matteo Ricci] referred to, and in each city the king has a treasury, and its respective treasurer, in order to charge the kingdom's rents, which are kept for the king's own expenses.

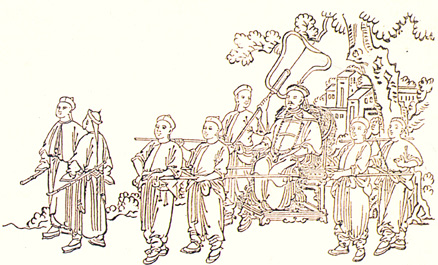

A Chinese government officer and his attendants.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da. HINO. Hiroshi, trans. [into Japanese], Tratado das Cousas da China [...]

(Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]). Tokyo, 1989, p.317.

A Chinese government officer and his attendants.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da. HINO. Hiroshi, trans. [into Japanese], Tratado das Cousas da China [...]

(Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]). Tokyo, 1989, p.317.

The king has one-hundred and fifty million in revenues and even though such marvellous things are uncountable, I would say that this could be true. Firstly, there is a lot of land, as the coast is around four-hundred leagues in length, thus being one of the sides of a square; the wall which divides China from the Tartar kingdom, which is the other [of the sides], and even longer; thus the other two sides should be as long as those, however we do not know for sure. All this land is very fertile, as mentioned, because they do not waste a single clod of earth. On the other hand, no-one can own fields or property, as everything belongs to the king, to whom they pay rents, or perhaps feudal tenure. Also there are no feudal masters. There are some churches {i. e., temples} with revenues. There are no hospitals, or monasteries, or even abbeys. 23 The king receives revenue from everything, just like a general tribute, which people pay him per head, mansion and home. He owns the warehouses and fluvial gates. He owns the salt, which he mines at his own expense, bringing in great revenue from there. In this way, he could only but be a rich person, especially for not [in his country] having plagues, famines or wars. No money leaves this land, rather it comes in. They still say that the king spends a hundred million on government and justice officials, and also on the armed forces and in the maintenance for the walls, and his household and on the border with the Tartars, and in the benefits given to the Colaus• 24 in his council, and his wives and family. All the remaining monies are kept with the other treasuries for any necessity that could arise.

One of the things which Father [Ricci] did not refer to [in his letter] was musk, which only exists in China and is exported all over the world, and in such quantities that there is no merchant who does not have six or eight quintals of it. They say it is provided by some little animals similar to ferrets which are caught in snares, clubbed to death and placed opened out in the sun; after being bled, they give the source of that perfumed balm. 25

The Portuguese living here in Macao are like vassals to the Chinese king, and as such give obedience and acknowledge Guangzhou, paying five hundred taéis in silver in tax each year, which are a bit more than that in Castillian ducados; and for the ships they load up, they pay according to the capacity and measurement of the vessel, and not for the merchandise, thus some carry six or seven thousand ducados, paying just two per cent. Almost all of them are married to Chinese women, who are not the daughters of nobles, but more like slaves or common people. [The mandarins] treat them badly, as in the audiences they negotiate on their knees, being at times forced to wait six hours in the sun without their heads covered. Civil or criminal litigation between the actual Portuguese is carried out by their Captain-Major and Teller; but those which involve Chinese are resolved by the mandarins and judges from Xiangshau26 and Guangzhou, often being handed over to the Portuguese to be whipped and publicly punished. [The mandarins] have captain António de Carvalho imprisoned at the moment, for a certain amount which are due in Macao to some Chinese merchants. And the prison is a dungeon where no sun or moon enters, full of filth and horrors, because [the Chinese] are very cruel with regard to prisons and legal punishments.

Your Majesty could pacify these kingdoms and be their lord with less than five thousand Spaniards, at least in the coastal areas, which are the most substantially populated areas in the whole world, and with half a dozen galleons, along with another half a dozen galleys {i. e., open rowing boats}, the coasts and neighbouring provinces of China could be dominated, just like all the South Seas and Archipelago, from China to the Moluccas, along the coast running by the islands.

You could take six or seven thousand soldiers out of Japan, through the Fathers of the Company [of Jesus], Christian, warlike people, more fearful of the Chinese than of death. And from the Philippines you could bring three or four thousand Indians from the 'painted' nation, which they call vizaias, 27 who are very energetic when they fight on our side, being far better soldiers than the Chinese, and they could serve as punishers. However victory does not depend on the size of the army, but on the heavens {i. e., the Grace of God}, from where our force comes. 28

Written in Macao in September, 1584.

Frontespiece.

HISTORIA / DE LAS COSAS MAS NOTABLES, / RITOS Y COSTVMBRES, / Del gran Reyno de la China, ∫abidas assi por los li- / bros de los me∫mos Chinas, como por relacion de / Religio∫tro y otras per∫ que an citado en el di-/ cho Reyno./ HECHHA Y ORDENADA POR EL MVYR. P. /mae∫tro Fr. Ioan de Mendoça de la Orden de S. Au / gu∫tin, y penitenciario Apo∫tolico a quien lla Mage∫tad Ca- / tholica embio com ∫fu real carta y otras cosas para el Rey de a- / quel Reyno el año. 1580. / Com vn Itinerario del nueuo Mundo. /

EN ANVERS, / En ca∫a de Pedro Bellero, / 1596./ Con Priuilegio.

*Translator's note: Words or expressions between curly brackets occur only in the English translation.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce

For the Portuguese translation see:

ROMÁN, Juan Bautista, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Historia do Grande Reino da China, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura":, Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.104-107 - For the Portuguese modernised translation by the author of the Spanish (Castilian) original text, with words or expressions between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese translation, see:

[ROMÁN, Juan Bautista], Relacíon de Juan Bautista Román, Archivo General de India, Sevilla (General Archives on India, Seville), Filipinas (Philippines), MS.29 - Partial translation from Spanish.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Juan Bautista Román's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, p.107.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics 《""》 - unless the spelling of the original Spanish [Span.] text is indicated.

1 "haytán"• [original Span.] or "aitão"[Port.] ("Aitão") = haidao• [Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's coastal defense forces with powers of jurisdiction upon foreigners.

2 "Lantao"[Port.] ("Lantao") = Daiyushan• [Chin.]: the island.

3 "nau[s]"• [Port.] ("nao[s]"): meaning in this context, Chinese junks - which could reach positively gigantic proportions.

4 This is conjecture.

5 "Cantão"• [Port.] ("Guangdong") = Guangdong[Chin.].

6 "Chincheu"• [Port.] ("Fujian") = Fujian [Chin.]: most probably meaning in this context, the Chinese province of that name.

7 "chumpim"[Port.] ("Chumpim") = zongbing• [Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's armed forces.

8 "tutão"[Port.] ("Tutão") =dutang• [Chin.]: the Viceroy or governor general of a Chinese province.

9 "esmeris" [singular: 'esmeril'] ("esmeris"): ancient artillery weapon similar to a musket.

10 "brocal"("[...] circular metal brace, [...]"): possibly a reinforcing ring sometimes placed at the mouth of heavy artillery cannons.

11 "corselete" [Port.] ("corselet"): a modified corset of leather or steel, worn to protect the chest.

12 "tutão"[Port.] ("Tutão"): (See: Note 8)

13 "chinfu"[Port.] ("Chinfu") = zhifu• [Chin.]: the Mayor of a town.

14 "[...] à gineta [...]"("[...] with short stirrups [...]"): lit: the same way as ginetes (small Spanish horses) are ridden, but in this context, short stirupped saddles.

15 The Ming's• capital, in actual fact, was relocated from Nanjing to Beijing around 1420, as a response to the growing threat of the Tartars who, in those days frequently made predatory incursions across the northern borders of the Middle Kingdom.

16 "chincheu[s]"[Port.] ("chincheu[s]"): most probably meaning in this context, the inhabitants of "Chincheo" [Port.: "Chincheu"], or Fujian• province.

17 This account has no factual basis. It could be referring to a confusing reference to an uprising in the Chinese garrison which happened in 1564 and ended up being quelled by the mandarins [Chinese government officials] from Guangdong, with the help of the Portuguese form Macao.

18 Patane and Joor were sultanships in the southernmost part of the Malay peninsula.

19 In fact the merchants from Fujian province maintained a dense trade network over all China's South Sea.

20 The author is referring to a letter by Fr. Matteo Ricci(°1552-+1610) which he translated at the beginning of his Relación [...] (Report [...]).

21The author refers here to sodomy, which was severely punished in the Iberian kingdoms.

22 This hypothesis is rather curious, because historians still discuss whether the Chinese press was the origin of the 'invention' of the same form in Europe today.

23 The author looked for analogies with European reality; but not all his observations were correct.

24 "colau[s]"[Port.] ("Colau[s]") = gelao• [Chin.]: the 'First Secretary of State'. There were six gelao each being a president of one of the liubu• (Six Tribunals), the supreme legislative entities of the Empire which acted under direct orders from the Sovereign.

25 The musk-deer (Moschus moschiferus), a common ruminant native of the Tibetan plains, produces musk in his preputial follicles.

26 "Anção"[Port.] ("Anção") = Xiangshan• [Chin.].

27 "visaia[s]"[Port.] ("visaia[s]"): the natives of one of the main 'tribal nations' in the Philippines.

28 Around this time the Spanish were funding large scale projects to conquer lands in the Far East, both spiritually and physically. In fact king Felipe II of Spain [Filipe I of Portugal] (°1527-r.1556[S]/ r.1580[P]-+1598) regularly received reports presenting plans to conquer several regions in Asia, from Cambodia to Japan, passing through China. These imperial dreams, motivated by the fame of riches which could be found there, were based on an obvious lack of knowledge regarding the terrain.

start p. 133

end p.