The King of Malaca, having arrived at the kingdom of Pão, 1 and seeing that there was no remedy for his misfortunes, determined to dispatch an Ambassador to the King of China, 2 begging for succour, that he might be enabled to recover the city which he had lost, reminding him, with the object of obtaining a favourable reply to his request, of the ancient friendship which the Kings of Malaca had always kept up with those of China, and of the obedience which they had shown them as their vassals; and in order to give a greater appearance of authenticity to this embassy, he desired that it should be accompanied by one of his uncles, whose name was Tuão{1} Nacem Mudaliar, in whom he reposed the highest confidence; and he, after receiving his order to depart, went and proceeded to embark at the river Muar, {2} whence he set sail in a junk with his wife, accompanied with certain Moors in his retinue; 3 and when he reached the city of Cantão, ·{3} which is the port of China whither all those who sail to those parts are accostumed to make land, the Governors of that city — in accordance with the ancient custom which they keep up — immediately sent of a messanger to the King, who was in the interior a distance of a hundred and eighty leagues, giving him notice of the arrival of the Ambassador of the King of Malaca, and asking that word of the King's pleasure as to what should be done might be sent, for the custom of China is that not a single stranger can pass beyond that port nor go to the King without his permission.

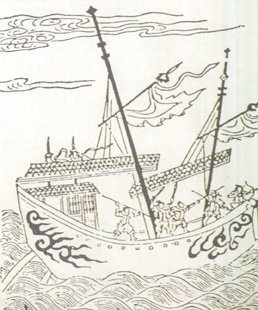

Chinese junk.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau - Instituto de Promoção do Comércio e do Investimento, 1966. p.75.

Chinese junk.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau - Instituto de Promoção do Comércio e do Investimento, 1966. p.75.

The messenger whom the Governor dispatched reached the city of Pequim, ·{4} where the King was, and delayed on the journey two months, and then returned with the reply to the Governors, to the effect that they were to permit the Ambassador, with the retinue in his company, to pass through the kingdom, and to give them everything that they required for the journey. When the Ambassador received this reply, he lost no time in making his preparations, and set out with his wife on the road to the Royal Court, and kept continuously traversing along the bank of a river{5} where there were very noble cities and very sumptuous edifices, of which I do not treat because it has nothing to do with this history. 4 On the arrival of the Ambassador to the Court, he was very well received by all the Lords and Governors of the land; and after some days elapsed the King desired to receive him in person, although this was not his usual custom, for no one sees him, and business is transacted by the men who govern the land. And after the Ambassador had performed his courtesy to the King after the manner and custom of the Chinese, he threw himself at the King's feet, and with many tears begged him that he would be pleased to assist the King his lord in his present trouble, for him he placed all his confidence.

Frontespiece.

In: Commentarios de / Afon∫o Dalboquerque cpitão geral & gouer- / nador da India. collegidos por ∫eu filho Afon∫o / Dalboquerque das proprias cartas que elle e∫cre / uia ao muyto podero∫o Rey dõ Manuel o pri- / meyro de∫te nome, em cujo tempo gouernou a India. Vam repartidos em quatro partes ∫eg´u- / do os tempos de ∫eus trabalhos. / COM PRIVILEGIO REAL.

[Lisboa, 1557].

Frontespiece.

In: Commentarios de / Afon∫o Dalboquerque cpitão geral & gouer- / nador da India. collegidos por ∫eu filho Afon∫o / Dalboquerque das proprias cartas que elle e∫cre / uia ao muyto podero∫o Rey dõ Manuel o pri- / meyro de∫te nome, em cujo tempo gouernou a India. Vam repartidos em quatro partes ∫eg´u- / do os tempos de ∫eus trabalhos. / COM PRIVILEGIO REAL.

[Lisboa, 1557].

The King ordered him to rise, and told him to relate all the history of the affair in order. He related it to him, for he had been an eyewitness of it all, and told him that the King his lord, after he had been overcome, had retired to the kingdom of Pão, and there he remained waiting, in hopes that he (the King of China) would turn a favourable ear to him, and assist him, with men and a fleet, to recover possession of the kingdom, to be revenged for the affronts which the Captain of the King of Portugal had given him; and although the King of China had already been informed, by the Chinese who had come from Malaca, of all that had taken place, 5he was glad to hear the Ambassador, and he enquired very particularly of him concerning the person and authority of the great Afonso Dalboquerque and of the Portuguese, what sort of men they were, and what was their manner of fighting.

The Ambassador, as he was a discreet man, gave him a very good account of everything, whereat he was very satisfied. And when these conversations were over, the King told him to go and enjoy himself, for he would dispatch him and do everything that he wished, but really he was unwilling to give his word that he would help the King of Malaca, for his intentions and desires were to keep on friendly terms with the King of Portugal and with his Captain Afonso Dalboquerque, and to send some persons to visit him, as well because of the great news which he had of his person, as also because of the good treatment that he had shewn to the Chinese whom he had found in the port of Malaca, and his desire to open the commerce in his land. And one thing which greatly helped this policy of the King of China was the complaints which the Chinese merchants made of the tyrannies of the King of Malaca had practised upon them in the matter of their merchandise, in the time when they were in his territory. 6

The Ambassador spent a long time at the Court without being able to get dispatch of his business, and during this time his wife died; and after some days had elapsed the King replied him, through the officials, excusing himself from granting succour which was asked from him, and giving his reasons why he could not do it, and the chief reason was the war that was on hand against the Tartars. With this reply the Ambassador set out without loss of time, and when he arrived at the city of Janquileu, and bethought himself of the unfortunate result of his mission and of his departed wife, he died of sheer grief, having given orders to build a chapel for his interment in the outskirts of the city, and therein he lies buried in a sepulchre surrounded by steps of lateen, on which he ordered an inscription to be placed, which reads: "Here lies Tuão Nacem, Ambassador and Uncle of the great King of Malaca, whom the eath carried off before he could be avenged upon the Captain Afonso Dalboquerque, lion of the sea robbers."

Revised reprint of:

[ALBUQUERQUE, Afonso Brás de,] The commentaries of the Great A. DALBOQUERQUE, Second Viceroy of India/ Translated from the Portuguese edition of 1774, /with Notes and Introduction, by Walter de Gray Birch, F. R. S. L., senior assistant to the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum; Honorary Librarian of the Royal Society of Literature; Honorary Secretary of the British Archeological Association, etc., 4 vols., London, Printed for the Haluyt Society, 1880, vol. III, pp. 131-134 [No. LXII] — vol. I, London, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, M. DCCC. LXXV., No. LIII; vol. III, London, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, M. DCCC. LXXVII., No. LV; vol. III, London, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, M. DCCC. LXXX., No. LXII; vol. IV, London, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, M. DCCC. LXXXIV., No. LXIX.

For the Portuguese text, see:

ALBUQUERQUE, Afonso Brás de, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Comentários do grande Afonso de Albuquerque, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.89-92 — For the Portuguese modernised translation by the author of the original text. with words or expressions in between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese text, see:

ALBUQUERQUE, Afonso Brás de, SERRÃO, Joaquim Veríssimo, ed., Comentários do grande Afonso de Albuquerque, 2 vols., Lisbooa, Imprensa Nacional- Casa de Moeda, 1973, vol.2, part.3, pp.148-152 — Partial transcription.

NOTES

The numeration of these notes specifically refer to the section of Afonso Dalbuquerque's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.85-86.

The prevailing numeration of these notes is indicated between curly brackets 《{ }》 and is cross-referenced to Walter de Gray Birch's English translation [WGB] of Afonso Dalbuquerque's original text, indicated immediately after, in between flat brackets 《[ ]》.

The contents of these notes have been transferred in their entirety exactly as they appear in Walter de Gray Birch's English translation [WGB] of Afonso Dalbuquerque's text, and do not follow the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

Whenever followed by a superciliary asterix 《 * 》, these notes' bibliographic references are alphabetically repertoried according to their author's name in this issue's SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY following the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

{1}[WGB, p.131, n.1] This the common Malay word for Lord or Master.

{2}[WGB, p.131, n.2] The river in Malaca, on which the city of Pahang or Pão is built.

{3}[WGB, p.132, n. l] Canton, · or Quangtung, · 23 deg. 12 min. N., 113 deg. 17 min. E.

{4}[WGB, p.132, n.2] Pekin, ·or Shun-tien, · China,39 deg. 53 min. N., 116 deg. 29 min. E.

{5}[WGB, p.132, n.3] This probably refers to the Yang-tze-kiang ·which is connected by the Yun-ho, Sha-ho, · or Grand Canal, with the Yun-ho, ·or Eu-ho· River, on a branch of which the city of Pekin is built.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Afonso Dalbuquerque's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.85-87.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics 《" "》 — unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated —followed by the spelling of Walter de Gray Birch's English translation [WGB], indicated immediately after, between quotation marks within parentheses 《(" ")》.

1 After the conquest of "Malaca"("Malaca or 'Malacca'), in 1511, the sultan who ruled the city took refuge in the kingdom of "Pão" ("Pan"), east of the Malay peninsula.

2 In those times Malacca was a vassal state of China, regularly sending tributary embassies to the Imperial Court of Beijing. According to the first edition of the Comentários [...] (The Commentaries [...]), after sultan Mahmud loss his town to the Portuguese troops, he retired extremely "anojado" ("disgusted") and disgruntled to the kingdom of Pan, where he stayed until the end of his life.

3 In a letter dated 1534 Cristóvão Vieira reports (See: Text 4 — Cristóvão Vieira) some notices on this Malay embassador and his visit to China.

4 The author repeatedly refuses to supply descriptive informations of the regions where the incidents which he narrates occur, alledging that more capable chroniclers had already done it. By this he is most probably making reference to Tomé Pires and Duarte Barbosa. (See: Text 1 — Tomé Pires + Text 2 — Duarte Barbosa)

5 The crews of the Chinese junks which berthed in Malacca's harbour where treated with consideration by "Afonso de Albuquerque" ("A. Dalbuquerque") during the conquest of the city.

6 The fictional prose of this passage is obvious, the apologetic intentions of the author being equally evident. The author uses the great majesty of the Chinese Emperor to emphasise the importance of Afonso de Albuquerque's being admired by the sovereign. In effect it is extremely unlikely that the Emperor Zhendge ·(r. 1 506-+1521) was ever concerned about the feats of the Portuguese Governor [Afonso de Albuquerque] or with the increment of trade between Portuguese and Chinese.

start p. 115

end p.