In this pluralist Spring, we are running the risk of reaching a common agreement and that, crowned with roses, we parade through the doorway which no longer offers more hopes of dispute, censorship and discontentment. Heraclitus said that one day everything would be nothing but fire; he did not prophecise that everything would be meat paste and apple tarts. How would perform a world incapacitated of frights and prophecies, thus becoming an asylum of vaporous souls and a planet of robots.

Artists who were an eventual vivacity in the sclerotic veins of civilization equally vanished in a sea of olive oil. People no longer pay them attention unless to palpitate invitations and pecuniary awards, to impart a lustre to the dead, or to smile at a photograph.

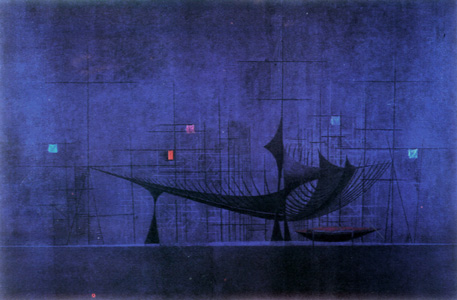

Amongst them there was one who escaped from the domesticated human swarm: it was the Eduardo Luiz whose paintings are presently exhibited in Gulbenkian and who, in life, was a loose cobble in the paved street. Of a bickering and clumsy mood, sufficiently lacking in diplomacy to seem inoffensive, Eduardo Luiz was a corsair anchored in French soil, without a treasure map, and with memories of wounds and battles. Agressive with everyone, shook the critics by the collar, and distributed unhappiness as if handing out alms. And, with a monastic devotion, he painted paintings that would be later be called mannerism for bankers. They are not. They are as perfectionist as mathematical operations and are much indebted to an ethic structured in an universal norm. He grabbed nature in a uniequivocal way, as an immutable datum. A nature of which men extract contentment with the suffering of its laws. What was refuted to him was based in the thesis by Aristoteles: the fact of mankind, as such, being devoid of human nature.

But what seems to me undebatable is that Eduardo Luiz painted admirably well, although without transcendence, being himself in what he painted. His bitterness and his coleric outbursts had an effect beyond the ideals of love and respect which prevail in normative relationships. A devastating effect which repeatedly threw out of balance the social cohesion of the group. This unclenched a somehow fanatical process in relation to him, and consequentely, in relation to his paintings. But, incompatibility with others was integral to his tactical beliefs. To him, people were unjust, ignorant and stupid. Towards both his antagonists and partners in dialogue, he was cruel and sarcastic.

The ultimate goal purports of all exerted pressure over the real phenomenon which is mankind in itself.

All convulsions and hurried adjustments which we are nowadays facing European society, most probably will proclaim a novel standard. But it is not a question of facing dangers but to find solutions to problems. The adventure of antagonism, the facile pressupositions of 'good' and 'bad', start looking old-fashioned.

A new generation is about to be confronted, not with emotional situations, but with the human reality that, in fact, has never before been tested unless sheltered by a conscious belief. A conscious belief which emerging from a normalized experimentation is no longer sufficient to reveal the reality of mankind. To believe, is a strategy aiming at good common sense. That is not enough. To believe must be a constant objection addressed to the conclusive authority.

I think that the formula applied to Eduardo Luiz was defective and incomplete. He was requested to abide to the Thomist clause that is basically to do well, be docile and reasonable. Instead, he belonged to an essential inclination of his nature which was painting, his reasoning being an integral element of this nature. His sensibility manifested itself facing the objects from which he expected the clash. He did not expect the same thing from people, or maybe he expected nothing else from people except a suspended sentence. For Eduardo Luiz to paint was not the performance of a virtuoso. Painting had a moral value. He was requested virtues with human motivations, slaying the human of his choice, the work of art in itself. Wrath broke loose. It could not be any other way.

Untitled.

1959. Oil on canvas. 89.0 cm x 130.0 cm.

Private Collection

* In: Cartas de Campo Alegre - XXV, Lisboa, "Diário de Notícias", 22 July [July] 1990.

start p. 143

end p.