Father Adriano de las Cortes was born in Tauste, province of Zaragoza, Spain, in 1578. He first set foot in the Philippines aged twenty seven, there to become Superior of the Tinagón mission by 1613, barely thirty five years old. In 1625 his superiors instructed him he had been chosen to be in charge of negotiating an important matter with the Macao authorities.

This decision was not exceptional. Since 1557 Macao had been an important city for Europeans in general and the Portuguese and Spanish with interests in the Far East in particular. The colony had become not only the doorway to China but also the crossroads of many cultures and modus vivendi. In 1578 the Society of Jesus established its own permanent Macao residence in the " casa de San Martín" ("St. Martin's House") and in 1582 the Jesuit Matteo Ricci arrived in the colony with the firm intention to evangelise the entire Empire of China. In fact, the Portuguese emporium stood not only as a maritime commercial fulcrum of worldwide importance but the colony also flourished as the base from which new doctrines, unforeseen ideas, customs and habits were to penetrate into China. No wonder that during the early seventeenth century Macao was considered to be an increasing source of potential danger to the government of the Middle Kingdom. It is not surprising that Fr. Adriano mentions a number of problems in his narrative related to the Portuguese trading establishment.

Obeying orders received on the 25th of January 1625 the Jesuit embarked from Manila to Macao in the galliot Nuestra Señora de Guía (Port.: Nossa Senhora da Guia, meaning Our Lady of Guia). The vessel was large enough, with sixteen to twenty oars and two masts, to carry ninety seven people of different nationalities, predominantly Portuguese, Spanish, Hindus and Japanese but also a few "moro" (lit.: "Moors"). Four missionaries also travelled on board, two belonging to the Society of Jesus. The hold was loaded with assorted goods and approximately one hundred thousand Pesos of silver ingots, property of some wealthy merchants from Manila and Macao.

In normal conditions the crossing should not have taken longer than eight days but from the moment of its departure they faced adverse weather conditions. Making slow progress and sometimes even sailing in the wrong direction the vessel finally reached Llocos province. The intention was then to bypass the westernmost tip of Luzon island and veer directly towards the continent, but due to the inclemency of the weather they had no alternative but to continue north towards the Babuyan and the Batan islands in the hope to approach the southernmost tip of Formosa (Taiwan), from whence cutting straight across towards the China coast and down along it, back towards Macao.

On the 16th of February, after twenty two days at sea hindered by strong winds, high waves and bad light making it impossible for the pilot to steer effectively through relentless thunderstorms, the galliot foundered on the shoals off the China coast two hours before dawn.

According to the manuscript of Fr. Adriano1 the shipwreck happened in the Kwantung [Guangdong] province, near Ch'ao-chou-fu ("Chauchiufu" according to the Jesuit), although he simply states that the galliot crashed ashore sixty leagues from Macao, on a beach one and a half miles from "Panchiuso".2

It is in this fortuitous manner that Fr. Adriano fell into the hands of the Chinese who were to keep him prisoner until Macao managed to release him almost sixteen months after the shipwreck. He was to die in Manila three years later, on the 6th of May 1629, by which time he had entirely narrated his "viaje de la China" ("travels in China") there, hiring a draughtsman to render illustrations to accompany his text. The result was three hundred and forty eight manuscript folios divided into two sections entitled Primera parte de la relación que escribe el P. Adriano de las Cortes de la Campañía de Jesús del viaje, naufragio e captiverio, que con otras personas padeció en Chauceo, Reino de la Gran China, con lo demás que vio en lo que della anduvo (First Part of the Narrative Written by Fr. Adriano de las Cortes of the Society of Jesus, concerning the Voyage, Shipwreck and Captivity which he Endured with More People in Chaucheo, in the Great Kingdom of China, and all that he Saw from the Places Where he Stayed) and "Segunda parte de la relación, en la cual se ponen en pinturas y en plantas las cosas más notables que se han dicho en la primera parte, citándose a los capítulos della y añadiendo algunos nuevos puntos y declaraciones sobre cada una de las pinturas (Second Part of the Narrative, which Renders in Paintings and Diagrams the Most Remarkable Things Described in the First Part, cross-referenced with Its Chapters Enlarged with Novel Matters and Descriptions Pertaining to each Painting").

The First Part [...] contains two hundred and seventy eight folios (until the verso of folio one hundred and thirty nine). The Second Part [...] starts in the recto of folio one hundred and forty two and ends in a rather abrupt way in folio one hundred and seventy four. Folios one hundred and forty and one hundred and forty one are entirely devoted to the Index of the First Part [...]. The manuscript closes with a number of folios where he writes "De la luz del Sto. Evangelic y Cristianidade que hay en la Gran China" ("About the Light of the Holy Evangelist and Christianity in Mighty China"). These lines seem to be a later addition, possibly suggested by his superiors.

It can be said that Fr. Adriano's story is mostly told in the First Part [...] which narrates the author's sea voyage and its most important accidents as well as the events which he witnessed or heard in China and that he reported as being his "vision" of that country. The whole two Parts are divided into thirty two chapters where reminiscences of personal experiences mix with vivid commentaries on Chinese culture, the latter's prosaic stature dramatically dwarfing the former.

The first chapters deal with the shipwreck and the ensuing capture of its survivors by the Chinese. These folios which contain the author's first impressions of China overtly express his negative feelings towards the Chinese. Such an attitude is understandable bearing in mind that, besides Fr. Adriano's deep emotion at the death of fifteen of his fellow passengers at sea, aggravated by the almost total loss of the survivors' belongings (including clothing), the group was attacked shortly thereafter by three hundred Chinese armed with spears, swords and arrows, brandishing harquebuses and throwing stones - "[...] without us having provoked them in the slightest.", says the priest. The situation of the survivors became increasingly bleak, the Chinese severing the heads of five members of the group. Miguel Matzuda (the Japanese Jesuit travelling companion of Fr. Adriano) was fiercely wounded by a harquebus and Benito [Bento?] Barbosa had one of his ears partially cut off. Such were the beatings and aggravations that Fr. Adriano emphatically wrote: "[He was] badly hit on his neck and [they showed strong] intentions of having the [head] of Salvador Carvallo [Carvalho?] chopped off, and beat the faces of other honourable Portuguese causing many a most deplorable maltreatment." (fol. 7 vo).

The thousand Chinese who gradually gathered on the beach took no pity on the dismal state of the survivors, in fact to the contrary, they took full advantage of their miserable condition, wrung ropes around their necks and dragged them along like collared cattle continually torturing them with beating and lacerations. The road lead to "Chingaiso, [...] a pleasant walled [...]" village where many people gathered to see the captives. After more beating and shoving Fr. Adriano was finally sheltered in a house and given clothes and food by his appointed caretaker. It is during these moments, while still in shock of horrific experiences and unprecedented cultural strangeness, that the Jesuit was introduced to novel customs and products (such as tea) which he would repeatedly untiringly observe with endless fascination during his period of captivity. He wrote: "Afterwards, I was given me some food, without even been asked if I wanted either bread or water. Also, a small bowl of badly cooked rice, meat and a chunk of pickled parsnip. Making some sign language I asked for water [...] it took a long while before I was given some, piping hot- as they drink it. I was dying of thirst. Realising that I was not drinking it [the liquid] they thought I had not requested water but something else [...]. [...] Once again I requested some cold water [...]; [...] and this time I was given it hot with a herb cooked in it[...]"(fol. 10 ro).

The initial circumstances at Chingaiso were traumatic. The Father feared for his life and those of his companions whom the Chinese continuously tormented: "[...] one of the Portuguese of our group asked me where they were taking him and their [the Chinese] answer was two blows to his cheeks in such a manner that blood spat from his mouth." (fol. 11 vo). But if Fr. Adriano narrates such excesses he also describes how certain Chinese have a more considerate behaviour with the prisoners. "[...] a good Chinese [...]" - as the author calls him - gave him a pair of espadrilles, a parasol and a petticoat for him to wear. The caretaker of Fr. Matzuda allowed them to meet and the two Jesuits made the most of these moments confessing themselves and praying together. Fr. Adriano admits how these reunions brought him much consolation.

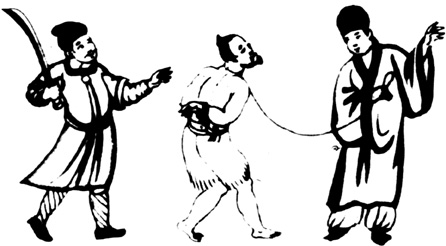

Prisoners.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p. 114.

Prisoners.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p. 114.

Soon after, the prisoners were interrogated in Chingaiso and had to face the bureaucracy of Chinese legal proceedings. They were questioned on their provenance, "[...] about moneys, jewellery and other merchandises carried [...]" (fol. 14 ro) on board and the type of ammunitions which equipped the galliot. The author found it strange not to meet a single Chinese who had ever been in Manila and comments that, after all, this place is not the "kingdom of Chincheo [... but a...] land inhabited by [...] quite fierce Chinese [...]." Fr. Adriano would later avow he had been mistaken at this time, and that in Chingaiso there were Chinese who had really been in Manila and Macao but apparently said nothing out of fear of displeasing the local mandarin.

During their stay in the village the Chinese were extremely curious about the captives and repeatedly visited the houses where they lodged, even trying to touch the prisoners' hair, hands and feet. The Jesuit described with a certain irony how the black [slaves] caused the greatest astonishment amongst the Chinese who "[...] are forever perplexed how they remain black even after having a wash [...]." (fol. 15 ro). Village men, women and children, mandarins and dignitaries, were all impressed by the strong constitution and manners of the prisoners, the way they ate with their fingers, their preference for cold water and their frequent gargling.

The Jesuit's first descriptions of Chinese culture deal with what impressed him the most. He remarked on the great number of government dignitaries going about accompanied by parasol bearers and how the parasols were specified to each dignitary's rank with particular attributes. He went on to describe women's garments and that men's clothing was not worth describing because it was similar to that of the Chinese living in Manila.

After a last interrogation by the local mandarin, on the 21st of February the prisoners left Chingaiso divided in small groups under armed escort, the soldiers carrying "small banners" with writings categorising them as [foreign] "pirates and thieves" who had attacked the Chinese natives. The convoy trailed along the streets of Chingaiso carrying on high the shipwrecks' survivors chopped off heads - nine of them by then. The last in the procession was a mastiff which had travelled in the galliot. Its trailing presence was the pretext for the author to explain that the Chinese not only eat dogs but are in the habit of clubbing them to death to make their meat "[...] more juicy, tender and 'abundant'."

Here follows a particularly elaborate section of the text. With inexorable realism Fr. Adriano repeatedly blended his report on the prisoners' progressive fate with hindsights on the culture of China - factually comparing its differences to practises more familiar to him.

The procession marched through a number of villages. At its third stop they met two important mandarins and the Father says that one of them is "[...] fourth in rank in the audience chamber of the kingdom of Chauchiufu, which in 'our' Castillian language is called Chauceo [... the other...] being the second most important of the kingdom, the Commander or General of the armies [...]" (fol. 22 ro). The narrative seems to imply that these two top dignitaries took an interest in the prisoners, for the first time caring to address them with the assistance of an interpreter - a Captain of their armed forces who had previously worked as a shoe mender in Manila.

The following day, after yet another interrogation, the captives reach a walled town called "Toyo". Fr. Adriano described it being surrounded by a moat where numerous vessels and bamboo rafts sailed. It is precisely at this point that the text relents from subjecting facts to preconceived notions and starts becoming more objective. In effect, the author remarked on the overwhelming impression that Toyo made on him: "It contained within its walls such a tall and extremely graceful tower that comparing it to any of the churches in Manila is practically impossible [...]." (fol. 23 vo). This phrase attests that the Jesuit had gradually started to ascribe merit to Chinese matters, valuing them relatively to experiences and images from 'his' previous cultural world.

The urbanity of Toyo becomes a pretext for him to comment on the high population density of China, something which had always greatly astonished him. Fr. Adriano succinctly explained that the reason for such high a birth-rate "[...] derives from the fact that men are allowed to have as many wives and concubines as they see fit to maintain or desire [... and that...] regardless their first [wife] giving them children or not, they never repudiate them but keep them and provide for them, taking a second one to discard if she does not procreate, then taking a third or a fourth until fathering successors." Nevertheless, he remarks that a polygamous lifestyle is not in everyone's reach "[...] it is said that [... some poor wretches...] being burdened by much poverty and many children, in order to avoid sustaining yet another newborn, shamelessly and without the slightest apprehension, publicly throw them into the rivers, regardless of their being unblemished and in good health, particularly if the infant is a female [... and that...] some honourable people and even some quite wealthy ones openly declare that, because they fear having problems with a too numerous progeny to provide for, they would rather sell a few offspring to strangers as slaves." Faithfully leaving a testimony of his experiences in this matter, he concludes: "Proof of this is the frequent sight of dead babies floating on the rivers, undoubtedly the consequence of what has been said." (fol. 24).

In Toyo the captives were again questioned. He remarks on the pomp and circumstance prescribed by the ranking system of the mandarinate; in fact he was so struck by the cohort of attendants preceding each mandarin, the courtesies, banners, music and colourful parasols that he illustrated the second part of this chapter with four plates.

Offenders wearing the cangue.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.180.

Offenders wearing the cangue.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.180.

The city of Toyo unequivocally marks a turning point in the Chinese experience of Fr. Adriano. His description of the sumptuousness of the city is made in a literary style of over-abundant comparisons. The fact that the mandarins sent him and his companions an "offer" of delicacies moved him to write: "[...] today, at the audience, thanks to the humanitarian feelings of the mandarins we started loosing our fears of approaching death and cherishing hopes of life. We also start being much more at ease in the Chinese cities." (fol. 27 vo) - thus succinctly revealing how much one's 'sense of reality' is derived not only from concepts but also from direct experience.

If what he initially saw and experienced in Chauchiufu had tremendous impact on his traditional values, his stay in Toyo marked an important reorientation of his views on China and things Chinese. Whereas at the beginning he correlated images and experiences from Toyo with those from the Philippines, he soon felt confident to extrapolate comparisons directly with Spain. He wrote:"[...] near it stood extremely beautiful towers built of stone and tiles, in architecture and gracefulness of no less standing than the Torre Nueva (New Tower) of Zaragoza in Spain, and the Micalet of Valencia." (fol. 28 vo). It is curious to note that these towers Fr. Adriano mentions were merely mandarins' tombs. Later on, and once again using a comparative methodology, he enthused about the bridges crossing the river Han Jiang: "We were greatly impressed by the extraordinary size of their [bridges] stones and even more by their [stones] solidity and fine texture, which surpass all those I had ever seen from Barcelona to Seville and from Mexico to the Philippines, both in buildings and in quarries." (fol. 28 vo).

As the narrative unfolds it is noticeable how Fr. Adriano's initial conjectures gradually become tamer and progressively transformed to another reality, later projecting an image of China quite different from that conveyed initially. Rivers, bridges, streets, buildings, shops, lakes, urban centres, suburbia, and especially cake shops, drinking places, fruits, meats and the hundreds of displayed goods hold him in a fantastic spell. Overwhelmed by such exquisite and wonderful variety of images, his description of the main street is a perplexed vision: "[...] what makes it most magnificent and more splendid than all the lanes in India and Spain are its twenty six arches [...] all with large and imposing stonework and strangely carved columns with marvellous architecture and tracery. To summarise, it was a complex assembly of features of unparalleled beauty which I had never seen before, non existent in Europe and each one enough to bring honour to any city in Spain [...]" (fol. 29).

By the end of February 1635 the interrogations at Chauchiufu proceeded with five mandarins in attendance who also called for a hearing before a mandarin of lower rank at Chingaiso. His accusations were horrible. He called the captives "pirates" and "thieves" who had ganged up together "to rob and pillage", and that once having set foot in China killed natives and concealed a treasure of silver which they were carrying. A curious fact is noted by Fr. Adriano that "[...] two or three of us, because of fair complexions and auburn hair, were taken for Dutch, who were their enemies." (fol. 31). This is a reminder that Fr. Adriano and his companions could not escape from being considered within a framework well beyond their own selves and actions.

The Chingaiso mandarin's lies were not discredited because of the difficulty of idiom, a serious problem the prisoners were not yet able to surpass. Fr. Adriano mentioned this handicap repeatedly in his narrative. As well as the difference in languages there was the succession of interpreters to prevent straightforward communication and any resolution of the conflict. Conscious of this problem, the mandarins of Chauchiufu not only repeatedly cross-questioned the captives but also changed interpreters until finding a Chinese who had lived in Macao and could speak some Portuguese.

This interpreter was to be of immense assistance to the prisoners. The Portuguese Antonio Viegas [António Viegas], Manuel Pérez4 [Manuel Peres] and Francisco de Castel Branco [Francisco Castelo Branco] resident in the same neighbourhood of Macao would speak on behalf of the whole group. The mandarins warned that reports about them would be requested [from Macao] and that all the other members of the group would be dependent on their integrity and trustworthiness. Confident of their credibility the Portuguese behaved with great audacity during the audiences: asking to speak, Juan Rodriguez (João Rodrigues) swore on his own life that he had given nine rings valued at three hundred Pesos to the Chingaiso mandarin. The "Viceroy" believed Rodrigues and severely reprimanded the mandarin and from then on the prisoners were given credit, the guard over them relaxed and clothes and food were offered them.

This series of hearings in Chauchiufu promised a potentially viable solution. The "Viceroy" declared that he would consult his homologue in Guangzhou in order to resolve their destiny. Meanwhile the prisoners were to be allocated to several villages. Consent was given for them to write to Guangzhou and Macao and once again luck was on their side. The Portuguese Francisco Castelo Branco wrote a letter to Macao and secretly entrusted it to a reliable Chinese. Fr. Adriano's narrative says that because all the other letters given to the mandarins were never delivered, Francisco Castelo Branco's missive "[...] was the instrument which would save our lives."

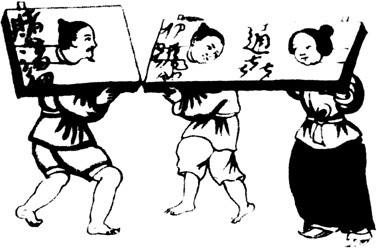

People's transport.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.174.

People's transport.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.174.

Fr. Adriano used his time in Chauchiufu to make acquaintance of the Buddhist bonzes and to join them at meals. Considering the preparatory information compiled on Chinese rites and customs by Ricci and his companions before setting foot in the Middle Kingdom it is quite probable that Fr. Adriano was equally knowledgeable of basic Buddhist practises. Aside from his deepest religious beliefs his narrative now develops with great ease into commentaries on a multitude of novel everyday objects. He related the general aspect of the bonzes, the colours of their robes, their socks and shoes, their parasols, 'rosaries' and cult utensils, their charities and penances. He also described temples and pagodas with great interest.

His fascination is noticeable in the text. The elaboration of the narrative expresses an emphasis on synchretic interpretation which attempts to "translate" some facets of this other faith. For example, he described a pagoda, noting its similarities to "[...] a St. Michael of ours [... and another...] not unlike a portrait [sic] of Our Lady holding the Child Jesus [...]." (fol. 42 vo). Despite his enthusiastic description of Buddhist practises, his own religious beliefs do not falter and he clearly states "[...] that our Christianity is much different [...]." going on that if some Buddhist rites are admittedly curious and others are simply ridiculous (such as their manner of collecting charity), the fundamental truth is that their practises are downright wrong.

On the 3rd of March, Fr. Adriano and thirteen other captives left for Panchiuso. The Jesuit described the enormous expanse of fields of wheat and barley, and the rice paddy fields bordering the road. He was also very surprised by the lack of horsepower in agriculture. Arriving in Panchiuso "[...] a village of about eight to ten thousand people [...]" they were taken to the mandarin and witnessed an event which greatly disturbed him. A Chinese having accidentally damaged a door the mandarin commanded he should be punished immediately with the batonade. This type of justice, presented here for the first time and qualified as "[...] refrainer of wishes and settler of complaints [...]" was extremely common in China, and this penalty affected the Jesuit so much that he became rigid with tension.

Cane beatings.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p. 176.

Cane beatings.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p. 176.

He described in great detail the manner of the culprit, the costume and the attitude of the executioner, the consistency of the cane, the manner of brandishing the lashes, the various types of strokes inflicted according to the whims of the executioner, the exact places where they hit the body and the cuts and bleeding they caused; all of which is made visually explicit in the accompanying drawings. There follows a description of the different current types of torture, punishments and other types of penalty inflicted in Chinese prisons.

In Panchiuso, six of the prisoners were lodged in a pagoda, allowing the Jesuit to observe the "superstitions" of the Chinese. If his previous commentaries on the bonzes showed a certain scepticism, he made the most of this particular instance to indoctrinate Christian believers in the righteousness of persevering in their own true faith. He gives himself as example and goes on to admit how, having overcome much hardship, he refused all food and wine given to him by the congregation of the pagoda as his Christian beliefs dictated and further attempted to explain to the bonzes the falsity of their devotion: "They invited me several times to share eggs with them and to taste wine, but I refused and told them that I could take no food from them, nor join them in their rituals, nor accept what I was offered, because that was forbidden to me. And pointing them the sky I told them that only the Almighty God who is in Heaven should be worshipped, and then I pointed to their pagodas and told them that those [divinities] were abominable to me." (fol. 50).

Panchiuso was certainly not a good place for the Jesuit. The hardships multiplied: much cold and little food, people falling ill and eventually dying. With so much to undermine the captives' morale, it is not surprising that he was also moved to comment on the "miseries" of the Chinese. The narrative unfolds in personal style counterpointing bad points (the misery and penury of their diet and clothing) with good points, going on to praise highly the excellent dishes he was invited to eat by an "important Chinese" which were so deplorably numerous, and the flavour of others offered by the director of a college. He juxtaposed events which happened during his captivity with others that took place after his release; particularly a banquet offered in "[...] Sciauquin [... to...] twelve fidalgos of Macao."

It is interesting to note while on this subject not only how Fr. Adriano presented information to the reader about the dietetic variety and richness of the native preparation and seasoning of the different dishes but also how he contextualised them within the different social strata.

Another subject which excited his curiosity was the abundance of tigers in the region and the imminent dangers they presented. His lines on this subject are most extraordinary. He claimed that tigers bit the heads off their victims to suck their blood. The whole of chapter thirteen, enlivened by illustration, attests to the great awe of the captives for these ferocious felines. He also reported that the beasts caught and slaughtered nine Chinese during the prisoners' stay at Panchiuso.

Fr. Adriano's imprisonment probably constrained him to dedicate a number of folios to describing the Chinese military, and the sensitivity of the subject possibly conditioned the tone of his remarks. It is curious that he described the soldiers in a manner more appropriate to a military report and unlike his usual lively style. It is also noticeable that some of these opinions are inconsistent with existing reports from other better informed sources or, at least, sources more experienced in contemporary Chinese military matters. In fact his presentation derived from a lack of "military" knowledge in the contemporary Chinese context. He wrote: "[...] their [the soldiers] skirmishes and drills seem more laughable than warlike [...] they perform a thousand contortions with their bodies [...] they are not very dextrous [...] and regardless how much they practise they do not behave like soldiers, exhibiting a total lack of military lustre. [...] Commit one thousand atrocities, run from right to left and from left to right, sit on the floor and suddenly spring up to their feet again [...]." And if this was not enough he ends up saying: "We used to go out just to observe them and have a good laugh. I say no more on this subject because I could only make ridiculous remarks about it." (fol. 65). This seems a peculiar attitude coming from the Jesuit, in strong contrast to the dedication to minutiae expressed in the accompanying drawings depicting soldiers with different headgear, attractive uniforms, shields, swords, cutlasses, spears, harquebuss and bows and arrows. To these are added a variety of flags, banners, an impressive number of percussion and metal instruments, flamboyant maces, javelins and packsaddles.

Fr. Adriano explained that he had little consideration for the Chinese militia. He considered that lesser ranks being punished by caning was sufficient to discredit the whole imperial army system. He emphatically stated: "Merely brandishing by a cane the [Chinese] king rules with great ease upon his subjects and in so doing he controls his domains."

Mandarin and his train.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.145.

The captives benefited from relaxed surveillance in Panchiuso and were able to go about with increasing freedom. Making the most of this advantage the Jesuit managed to follow the teaching method in Chinese schools'. He remarked admiringly on the great number of schools per capita and says: "[...] there is no small village of twenty to forty houses without a school or a community or even a [main] street without several schools." He promptly deduced that this overwhelming number of schools was due to the "[...] great number of children and also because each school is the sole domain of a teacher who never has more than twelve to fifteen children in his class. Each teacher entirely and exclusively shares his days with his students." (fol. 68). He also commented that meals were usually shared jointly by the teacher and his pupils.

Next he mentioned the Chinese government examination system, explaining it to be the basis of the hierarchy of mandarin's rank. He went on to discriminate between the types of knowledge of different Chinese social classes. Then he specifically elaborated on a crucial point which - according to him -is fundamental to the structural distinction between Chinese and Spanish education methods: "[...] regardless of being destitute, a simpleton or a brute it is quite rare for a child not to learn the rudiments of reading and writing, as it is equally rare among the most powerful in whatever capacity not to be able to read or write."(fol. 67).

It is interesting to note that Fr. Adriano's curiosity for unusual matters is reciprocated by the Chinese. His inquisitiveness is counteracted by that of the locals who "[...] were always anxious to see us scribbling and coveted even the smallest bits of handwritten paper with our writing which they showed to the people of other villages who had not been in contact with us." (fol. 67).

The major factor in this amiable relationship between the captive and the Chinese was probably their reciprocal interest in novelty. In order to present his reader with as complete as possible a panorama of China and things Chinese, as promised in the title of his work, Fr. Adriano examined different facets of the country's lifestyle in succession. Endeavouring to accomplish what he had set out to from the beginning he proceeded to dedicate six chapters to what might be generically called the "economic culture" of China.

The scope of this topic is quite vast. He started by dedicating three chapters to cattle raising, fishing and agriculture, followed by another three on mining and siderurgy. These he accorded to stand comprehensively for the contemporary economic system of China. The first of these chapters focused on animal foods and is a repertory of their abundant variety. Pigs, roosters, chickens, ducks, all sorts of anatidae, geese, pigeons and partridges are mentioned, as well as other edible wild animals such as rats and snakes. He warned that despite this enormous variety the Chinese were frugal at table, "[...] were they to imitate the Europeans in their voracity for meat instead of eating with parsimony; the extreme fertility of their [Chinese] lands would not suffice to feed the entire populace of the empire." (fol. 75). He closed this topic stating that the Chinese ate considerably more fish than meat with great detail of their methods of breeding fish and their good upkeep of fishpond farms. In the following two chapters he spoke of fruits, vegetables and cereals planted and cultivated in China.

The sequential 'set' of chapters opens with chapter nineteen and deals with "local produce" and metallurgic production. The first topic was familiar to both Fr. Adriano and the Portuguese from Macao. He described how native merchandises were mainly exported via two different routes from China to Japan and India; the first implemented by the Portuguese in Guangzhou and the second by the Chinese from Fukien [Fujian] in Amoy [Xiamen]. He claimed that the "kingdom of Chincheo" belonged to the maritime province of "Oquiem" [Fujian], being the nearest province to the Philippines and that because all the Chinese overseas merchants traded from Chincheo, they were known as "chinos chincheos " in Macao and the Philippines ("Chinese from Chincheo"). He distorted and abbreviated these denominations going on to say that "[...] the Europeans call them Chinese and their land China." (fol. 80).

These "Chinese from Chincheo" owned gold, pearls, rubies and stocked quantities of musk. They traded large amounts of silk and all sorts of textiles, fine sugar, fruit preserves and medicaments, specialising in "la purga de China" ("the China purge") and "palo de China" ("China stick") - which the Father tried - and rhubarb. He particularly remarked on their wide range of inks and stated that "[...] they have the best and most delicate in the whole world."

He also expressed surprise and commented on their good metal and wood craftsmanship, telling a surprising story on this matter. Once "[...] a well respected person [...]" who lived in Manila was afflicted by a strange disease that provoked the loss of his nose. Being disfigured, he had a Chinese craftsman "[...] make him a lively pair of red artificial nostrils which fitted the cane of his nose well. They were attached to a pair of glasses which were kept in place by side stems firmly held behind the ears. And so he resolved his ugly look successfully." (fol. 84) The craftsman eventually returned to China but later in life was back in Manila with hundreds of fake noses "[...] as if expecting that once having replaced a nose successfully he was going to find a thousand people also in need of prosthetic noses." The story is so fantastic that the Fr. Adriano finds it necessary to confirm that "[...] this is a true story."

Next he commented on a topic which nagged him greatly: the Chinese code of practice in which greediness "[...] as a matter of principle, never allows for leniency [...]." He could well have used himself as a living example of this exploitation but cleverly chose to address it at a commercial level, telling how this practise was blatant among the Chinese who traded in Manila and how pitifully it was inflicted on the Portuguese merchants in Guangzhou who had to endure "[...] a thousand vexations and humiliations during the [annual trade] fair [...]" (fol. 84 vo). He went on to describe in great detail how Portuguese merchants were frequently detained during this event, being released and allowed to return to Macao only upon payment of a hefty sum. And that [the Chinese] not satisfied which such impudence, arrested any Portuguese they met in their land immediately, under pretext of being a thief, an abductor of minors or perpetrating "[...] whatever might be forbidden in China [...]" who is not released from confinement without paying a considerable amount of money. Such facts were a pretext for Fr. Adriano to list and discourse upon the many expediencies the Chinese resorted to in order to accumulate wealth.

The narrative proceeds with the author noting the great care they took to recycle products from used goods. For example the loose bristles of a hair brush and the hairs of their pigs went to manufacture paint brushes; their animal manure went to fertilise the fields; their old clothes were shredded to weave blankets and people competed for the job of sweeping shop floors in expectation of gathering specks of silver dust which might have fallen and got trapped in the cracks between the paving.

Soldiers and weapons.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza Editorial, 1991, p.210.

Fr. Adriano was also conscious of the importance of the country's social hierarchy. The next chapter is partially dedicated to this class "network". He pointed to the distinctions between merchants and mandarins and makes reference to the "king [emperor] of China", stating that he is immensely rich despite his enormous expenditure on family, concubines and eunuchs - a noticeably uncomfortable subject for the author.

After briefly mentioning the government of China, he dedicated some folios to what he called the "[...] nature, attitudes and propensities of the Chinese [...]." He described the Chinese people as well built and tall, of white complexion, amiable character and healthy looking; saying their eyes were black, almond shaped and small; their noses short and flat. He mentioned jokingly that when they wanted to describe an ugly person they said he had "[...] a nose like 'ours' [Westerners]." He also mentioned that Chinese men in general had little body hair and depilated themselves "to exhaustion", going on to compare that "[...] their [beard] is never as dense as 'our' [...] among them being much praiseworthy to have a fair amount of facial hair [...] such characteristic [...] helping them to reach the status of mandarin." (fol. 96 vo).

After describing their physical traits Fr. Adriano examined their moral conduct. Possibly due to the bad experiences suffered during his captivity his words are more heated than usual:

"[...] they are heartless souls [...] without the slightest shame, much given to the pleasures of the flesh and other practises which greatly contradict the laws of nature [...] and great thieves. Most cunning, perfidious, liars, lacking friendship, sincerity or compassion with foreigners [...], extremely ambitious [...]." Being aware of the possible ambiguities and misinterpretations of the word "ambitious", he relented his 'negative' line of thought and explained that much of the great genius of the Chinese was derived from their positive drive which made them "[...] excel in the ability and ingeniousness to master all sorts of crafts, considering all equally meritorious and none less honourable than the other." (fol. 98).

Fr. Adriano interrupted this theme to make reference once again to his personal experiences, acknowledging that during the previous few months he had had the opportunity to observe the extraordinary talents of the Chinese in the arts and crafts. He concluded these later considerations on the Chinese by reformulating his former incisive remarks, adding a note to explain that the reason why this subject had been so extensively dwelt on was the necessary need "[...] to unravel what the Chinese so cautiously try to conceal about their civilisation."

Meanwhile, the mandarins had said nothing to the prisoners about their future. From April to June the mandarins from Chauchiufu travel several times to Guangzhou to deal with matters relating to them. Twelve of the prisoners were taken to "Quimir", a town a day away from Chauchiufu, to render further statements to the mandarin in charge of the soldiers who arrested them in Chingaiso. Despite all the secrecy shrouding the affair, some letters arrived from Guangzhou together with items of clothing and thirty four Pesos forwarded as pecuniary assistance by some Portuguese who had recently been in the city. The latest news was alarming. Macao had been virtually isolated from the mainland and war with China was imminent. The adverse effect of all this was immediately felt by the captives: security precautions were tightened and they were closely guarded by soldiers.

Between July and August Fr. Adriano received nine letters from Guangzhou and Macao. This correspondence assured him that both Portuguese and Spaniards were trying their utmost to secure the prisoners' freedom. The greatest impediment to progress in the release conversations was the refusal of the mandarins to give restitution of the galliot's silver cargo. Despite all, about twelve captives from Quimir were freed to return to Macao.

A further letter from Fr. Simón Acuña, written in Guangzhou on the 30th of October reported that the Jesuits were also negotiating for the release of the captives. It tells that after renting a boat for three hundred Pesos and paying two hundred more for the return trip, the whole rescuing operation had fallen short with the arrest of the Chinese in charge, by order of the mandarins.

Fr. Adriano and his companions seemed to be up against a number of aggravating circumstances and by then were so deprived they had to resort to begging from door to door. The author accounted how as time passed even the soldiers responsible for guarding them seemed oblivious of their existence; not only neglecting to provide them with the means for survival but also being careless of their whereabouts. Taking advantage of this he explored the region surrounding Panchiuso, visiting "Amptao", a town which he liked a lot for its thriving movement of boats and people. He succinctly describes this metropolis as "[...] the provider of goods and the heart of the kingdom of Chauchiufu [...]." He also visited "Saiting" which he considered less interesting. It is on the way to this town that he came across "musk" hunters and observed the tribulations of one of them. He found this hunt so fascinating that he not only related it in great detail but also illustrated the text with two accompanying plates of hunting scenes.

A boat arrived at Christmas to take the captives to Guangzhou. The sudden deaths of the "Viceroy" and the "third" mandarin of Chauchiufu seem to have been to their advantage. On the 15th of January 1626 a group of sixty soldiers accompanied them on the first leg of their return trip. The journey from Chauchiufu to Guangzhou took twenty three long days due to obligatory stops in many important towns and because- according to Fr. Adriano - sections of the road were mountain passes which meandered endlessly north and south.

Prisoners.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz,

intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid Editorial, Allianza, 1991, p.114.

He also described in detail the different types of embarkation of the "maritime culture" of China. He is quite observant of the range of riverside lifestyles and their distinct practises, and remarked on the "[...] fishing with maritime crows [...]" - which were in fact cormorants.

His account of the journey is extremely colourful, rendering people, bridges and villages pleasantly. He also described a number of towns but categorically stated: "[...] I felt that none of them, not even Fuchiu, were as imposing and as beautiful at the city of Chauchiufu [...]." (fol. 126).

Only his description of Guangzhou seems to throw the previous cities into the shade. He reached it on the 26th of February and was immediately impressed by the extent of its urban sprawl. In order to describe the conurbation more adequately, he divided it into "[...] four great cities [...]." The first, the 'floating' Guangzhou, embraced all those who lived on boats or whose life sustenance derived from river activities. The second covered the outskirts of the urban centre comprising the dwellings of the most humble and poor. The third was the zone "[...] within the first wall [... a vast neighbourhood called...] the new city [...]. The fourth was [...] the old city [...]" surrounded by the second wall and the residential area of the most important people and the mandarins. He said that- according to what he had been told- Guangzhou had more than five hundred thousand inhabitants and added: "[...] I do not know how many they really are, but I have never seen so many and, if not elsewhere in China, I don't think I will ever see so many people again."(fol. 127 vo).

He went on to analyse the different typologies of buildings in China, to which he devoted a whole chapter. He divided them into a number of categories: houses of mandarins and wealthy citizens, pagodas, residences of 'middle class' people, and "poor people's" lodgings. He writing is extremely detailed and accompanied by a number of illustrations with plans of the buildings described. This chapter also mentions, if only summarily, a number of factors common to all great Chinese conglomerations: their multitude of thoroughfares, their stone archways (features which he had enjoyed so much in Chauchiufu and Toyo), their embracing fortifications with tall crenellated ramparts and, most of all, their outskirts bursting with shops and stalls, noise and colour.

In Guangzhou he was summoned several times to the presence of the "Anchau" ("[...] this is how he [the magistrate] is called by the Portuguese, and he deals with all the criminals in the province [...].") who invariably asked him the same questions as all the previous mandarins. Finally, the "Anchau" being convinced beyond doubt that the silver had been embezzled by some high Chinese dignitary, he issued an order for the arrest of the mandarin of Chingaiso.

This major problem being satisfactorily resolved, the survivors sailed down river to Macao where they arrived on the 21st of February 1626. They were welcomed with great joy and slowly recovered during the following weeks from their privations.

On the 30th of April three galliots left for Luzon escorted by a number of smaller boats. But before they reached their destiny a tremendous thunderstorm sank the admiral's vessel drowning many "[...] merchants and important people [...]" and sinking goods worth around five hundred thousand Pesos.

On the 20th of May, Fr. Adriano de las Cortes set foot once again in the Philippines, leaving behind a difficult time of much uncertainty and hardship, but carrying with him the memories of an unforgettable experience which he was to leave shortly for posterity as a unique document on Chinese culture.

Translated from the Spanish by: Carlos Figueiredo

NOTES

1 CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., MONCÓ REBOLLO, Beatriz, intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Allianza, 1991.

2 Adriano de las Cortes translates the Chinese names to Spanish, giving to many the ending 'so' (i. e., "Panchiuso", "Chingaiso"), possibly his alternative for the character 'hsien' which usually stands for 'district'.

It is also possible that the places he mentions incorporated military garrisons at the time which contemporaneously were also given the syllable 'so' at the end, similar to the appellations of their commanders.

Translator's note: Chinese names are written as they appear in the original manuscript only when they first occur, between quotation marks [" "], otherwise they are written as transliterated by the author. Whenever possible, pinyin romanisations are given to the author's transliterations, between flat brackets [ ].

3 I am indebted to Prof. Lisón Tolosana for the copy of Adriano de las Torres' original manuscript in the Collection of Manuscripts in the Spanish Language, in the British Library, London.

In this text, words between quotation marks [" "] are translations/adaptations of the original Spanish citations. The folios indicated between parenthesis [( )] refer to the location of the citations in the manuscript mentioned therewith.

4 Adriano de las Cortes also renders the Portuguese names into Spanish, substituting the native final 's' by a 'z'.

5 I am specifically referring to the travel report manuscript of captain Miguel de Loarca, which I am presently transcribing. The same opinion is expressed in the writings of Fr. Rada and Fr. Mendoza, who are equally dissonant from those expressed by Fr. Adriano.

*Lecturer at the Complutense University, Madrid.

start p. 31

end p.