§1. THE GIGANTIC LUOZHOU

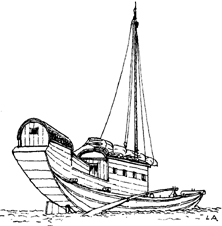

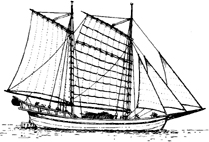

Portrait of a Trading Ship.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

ALEXANDER, William-MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [33]

Portrait of a Trading Ship.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

ALEXANDER, William-MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [33]

In May 1827, Captain Frederick William Beechey, commander of the frigate Blossom, ran aground on Luozhou Island, then a Chinese possession located south of Japan.1 It was forbidden to moor in the bay but Beechey managed to disembark his sick and remain in the area for about twelve days. During the stay an artist, William Frith, drew a Chinese junk which at the time was on route to the mainland carrying the annual taxes on board. 2

In a way the enormous junk seen by the men on the Blossom in 1827 marked the end of a cycle begun centuries earlier with Marco Polo. The sighting of such a huge vessel was living proof of the existence of unique vessels which were the antithesis of western nautical traditions. In the years following the Blossom's time in the Far East, the Chinese Junk, an unknown and unappreciated giant until then, came gradually out of obscurity.

§2. A BRIEF LOOK AT THE JUNKS' HISTORY

2.1. MARCO POLO

Marco Polo, the late thirteenth century Venetian explorer, was called a liar when, following a year's absence, he told his contemporaries of his extraordinary adventure in the Chinese court, in an unknown corner of the world. The ships he described were superior to anything a worldly European of the time could imagine: they had a big strong rudder, several masts, cabins for a number of passengers and even watertight compartments in the hull which prevented sinking in the event of hitting a reef.

At that time in Europe the central rudder, which Marco Polo had already seen in China, was only a recent addition after thousands of years of using a lateral rudder at the stern of the ship.3 Half a century after Marco Polo, the Muslim explorer Ibn Battuta came across thirteen Chinese junks built in the cities of Zaytun and Sin-Kalan in the port of Calcutta, India. He described their staysails and even briefly how they had been constructed. The junks "[…] are equipped with oars which are as big as the masts."4

2.2. THE EXCELLENCE OF ZHENG HEI VESSELS

If people at the time accused Marco Polo of lying, today historians, archaeologists and metric experts still speculate on whether the Chinese ships which reached the Indian Ocean more than a century after his departure, had in fact the dimensions which reports gave them. Given the documentary evidence, even the most pessimistic admit that Admiral Zheng He, a eunuch and favourite of the Imperial Court, travelled to India with junks of up to seventy metres long on several occasions at the beginning of the fourteenth century. The fleet was on a grand scale just like the ships. Some junks, accounts say, had up to nine masts and cabins for dozens of passengers. If we were to interpret the dimensions given in these accounts literally, the vessels would exceed one-hundred metres in length. If this were correct, Zheng He's junks would have been the biggest wooden ships in history.

When the Portuguese reached the Indian Ocean, there was still talk of these unusual ships which formed part of the huge, peaceful fleet which had sailed the coasts of India and Southern Arabia decades earlier. In the course of Portuguese interaction, evidence arose of the presence of sailors from the vast Chinese continent. In April of 1504, on the Island of Socotoka, entrance to the Red Sea, the crew of the nau Setubal heard talk of "[…] junks, white men like us".5

In Coulao at the end of the same year, the Portuguese managed to see four or five chins (Chinese) "[…] who were white like the Germans or Dutch."6

Another world opened for the first Portuguese sailors when they finally reached the coasts of China at the beginning of the sixteenth century. The chins's vessels were different in many ways: their sails, the shape of their hulls and the way they handled. Some had verandas on the stern. The oars were movable and could be hoisted up in the event of running aground or in very shallow waters. A handful of Portuguese had already seen these strange vessels in the waters of Malacca but direct contact with Chinese nautical ways was brought about this time with definitive interaction. For Quirino da Fonseca, a naval archaeologist, some influences were immediate: in the second decade of the sixteenth century he saw the several layers of wood on the outer lining of junks near Guangzhou, a technique which the Portuguese naval engineer, Fernando Peres de Andrade, had 'brought' from the Portuguese shipyards specifically to protect the ship's hull from sea worm attacks7 The veranda on the rear poop deck had the same origin according to Fonseca.

Apart from the enormous differences, Chinese vessels also shocked Westerners by the sheer number of sightings recorded. The British historian, Charles Ralph Boxer, cites the eye witness account of Christovão Vieira of the moment when just the Chinese province of Fujian had junks "[…] by the million."8

In spite of the different forms of resistance shown by Chinese society to contact with sailors, merchants or European diplomats, missionaries would soon have the chance to get to know Chinese ships at close hand.

2.3. MISSIONARIES' ACCOUNTS

Some will appreciate this: in 1549, St. Francis Xavier complained of a Buddhist altar which he found on the junk he was travelling on as a passenger. However this religious man was left with a favourable impression of the oriental ship. Later in the seventeenth century other accounts will vary between favourable and negative comments. 9

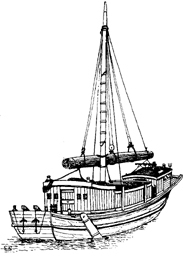

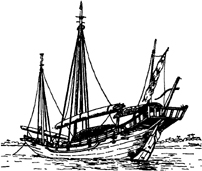

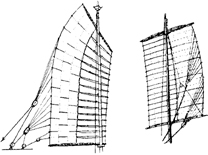

A Sea Vessel Under Sail.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

In: ALEXANDER, William - MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [81].

A Sea Vessel Under Sail.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

In: ALEXANDER, William - MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [81].

Ports like Macao or Manila in the Philippines were to play a vital role throughout the centuries in maintaining contact between the two cultural worlds. In the seventeenth century, around thirty junks docked every year on average in Manila Port, a city where at the beginning of the century around thirty thousand Chinese lived. 10 At the end of the seventeenth century the French missionary, Le Comte, wrote of his surprising admiration for some of the junk's characteristics: "Their boats are made of good, light wood which make them worthy of all the praise anyone has for them. They divide the vessel into five or six compartments whereby if they hit a reef which causes a gash or rupture to their hull, only a part of the boat fills with water and the others remain dry, staying like this until they can repair the hole in the other compartment."11

2.4. SAILORS' CONTEMPT

The development of international trade in the Renaissance also brought about a rapid development in marine boat building in Europe. In the eighteenth century vessels involved in ocean-going trade already had little in common with the small ships used for the Discovery voyages of the fifteenth century. During the French Campaign in India, in the second half of the eighteenth century, large commercial vessels were no more than a 'civil' version, with crew and light artillery, compared to war ships with sixty-four modern canons. In comparison, the Chinese junk seems not to have evolved and had by then lost its obvious technical supremacy of two centuries earlier when the first Europeans had arrived.12 But the number of junks at sea in China continued to surprise observers. In 1832 Charles Gutstlaff, a Dutch missionary, watched the flow of traffic for several days as junks entered Shanghai port and recorded a half day when four hundred went by. Gutztlaff added it all up and calculated that one hundred and forty six thousand of these vessels docked per year. 13

2.5. PÂRIS'S ADMIRATION

A Western point of view of how these exotic vessels are going to gradually evolve in the nineteenth century, the period when nautical archaeology came into existence.

One of the pioneers of the new science was a young marine official from the French Army, Pâris, who throughout a trip from the years 1830-1832 in the frigate La Favorite, collected drawings of various exotic vessel designs in the Eastern Seas. A new wave of interest grew out of this. Pâris, with the help of different collaborators who designed ships in other parts of the world, soon became interested in the overall number of ships sighted worldwide. Paris, then, 'captaine de vaisseau' (ship's captain) published the first description of junks in 1841. Observing war junks, Pâris spoke of the "[…] anomalies of Chinese construction […]",14 admiring the positioning of the widest part to the extreme rear, and of their keel in the shape of 'a duck' inspired by observing nature. 15

Presented with the novel solutions developed by Chinese boat builders, Pâris said, "[…] these bizarre people seem to have chosen the opposite to everything done on the other side of the world."16

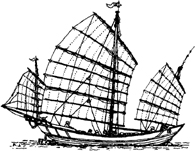

Three Vessels Lying at Anchor.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

In: ALEXANDER, William - MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [49].

Three Vessels Lying at Anchor.

1797. WILLIAM ALEXANDER.

In: ALEXANDER, William - MASON, George Henry, Views of 18th Century China: Costumes, History, Customs, London, Studio, 1988, p. [49].

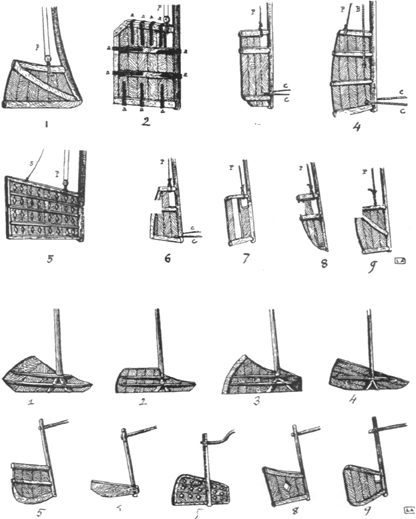

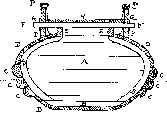

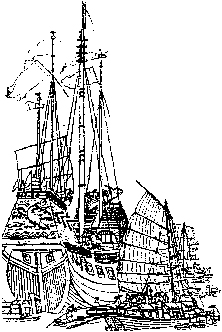

TOP: Rudders of oceanic junks.

BOTTOM: Rudders of river junks.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part 2, estampas [ills.] 36-37, pp.92-93.

TOP: Rudders of oceanic junks.

BOTTOM: Rudders of river junks.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part 2, estampas [ills.] 36-37, pp.92-93.

While Pâris and his collaborators were sailing and making drawings, another pioneer, Auguste Jal, the founder of nautical archaeology in Paris, was breaking ground in the field of a subject still in its infancy. Inheriting the humanist tradition of the Renaissance, the young archaeologist concentrated most of his energy on the reconstruction of ships from classical antiquity in Europe. The sources used for these reconstructions were pictures and ancient texts, or rather fragments in the majority of cases.

By proposing a wider vision of nautical ethnography and in observing contemporary vessels in all their variations, Paris had paved the way. From this time on detailed questions are broached like the introduction of axis rudders in marine construction and the use of the compass in navigation. In this new approach to ships, the Chinese junk stands out and takes its place quite apart within the history of technological developments.

2.6. THE JUNK AS A NAVAL LABORATORY

Suddenly Western observers realised that far from being rustic and backward, Chinese naval technology had been a model of pioneering design throughout history and continued to be so in the nineteenth century. The axial rudder, a version evolved from lateral rudders already evident in reliefs from Ancient Egypt, had been known in China long before being put to use in European ships.

The watertight compartments in the hull described in Marco Polo's accounts, and in others later, were in fact an essential step in marine safety. According to Worcester, an historian on junks, the first Western ship to apply this technique was Nemesis, a steam-ship built in 1840. 17

The junks' actual sails, analysed in more detail, revealed their great effectiveness due to the sails' semi-rigid structure.

In 1847, during the time that China was facing defeat by the Western Nations during the Opium Wars (1839-1842) and their huge ocean going junks were suffering the consequences of western involvement in maritime trade in the Far East, a Chinese junk called the Keying left Quiying and broke the cultural isolation adhered to up until then.

Purchased in China by a small group of enthusiasts, among them Captain Kellett, who commanded the large junk, the Keying left Guangzhou on the 19th of October 1846 but with some difficulty: according to the British ship owners. It had been necessary to 'buy' the authorisation to take this traditional vessel for local trade outside Chinese waters.

Built of teak, the Keying was, according to some crew, around a hundred years old when it began this new voyage, the longest in its life. It left Hong Kong on the 6th of December 1846, en route to England. The junk was going to be used as the venue for a floating exhibition of Chinese art. 18

The Keying.

This junk with a capacity of around eigth hundred tons, was forty eigth meters long and ten meters wide.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 3, estampa [ill.] 77-bottom, p. 147.

The Keying.

This junk with a capacity of around eigth hundred tons, was forty eigth meters long and ten meters wide.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 3, estampa [ill.] 77-bottom, p. 147.

With a capacity of around eight hundred tons, nearly forty eight metres long, ten metres wide and drawing 4.8 metres, the Keying caused public amazement. During its stopover on the Island of Santa Helena, in the South Pacific, the ship's log recorded for Monday nineteenth of April, 1847, the continual presence of visitors totalling three thousand on board that day. 19 The same thing happened in New York where the enormous junk arrived on the 9th of July in the same year. 20

With a prow height of nine metres above sea level and stern height of 13.5 metres, the Keying demonstrated the difference in a Chinese solution for sea worthiness. With a circumference of three metres and approximately twenty-nine metres in height, the main mast took a sail which weighed nine tons all set up. It took forty men to handle this with the help of a winch.

The Keying arrived in England at the beginning of 1848. The junk had been converted into a floating gallery and the decks were arrayed with a variety of furniture. Even a brochure had been printed by the organisers which served as a catalogue. The British public could also see the junk's big movable rudder which could be dropped up to a depth of more than seven metres, around 3.6 metres lower than the keel's depth. The wooden anchors made of teak were ten metres wide and were another astonishing aspect of the junk for the European public who visited the Keying. " There was nothing quite like it in Western waters.

During the North Atlantic crossing, before reaching England, the Keying had met the worst storm of the entire trip since leaving China. The way the ship handled in the storm was praised by the Europeans on board. The ship's log for the 25th of February 1840, just after the storm's worst moment read: "Vessel behaving beautifully well."

The Keying was no more than an exotic diversion for high society. But for experts on the subject, the books written by the Frenchman Pâris, published from that period, constituted a lasting historical account of the different nautical technologies in a period which marked a turning point, with the motorisation of vessels having already brought about fundamental and diverse modifications. 21 Changes were even faster in China's case due to the opening of contact with Western commerce and the ensuing decline of sea transport, which had mainly included large junks up until then. 22

As a foreign naval officer just travelling through these countries, Pâris only had brief opportunities at his disposal to complete his studies and complained of the little time allowed to examine vessels which did not enable him to observe the types of keels below the water line. 23 In Macau, Pâris was finally able to examine the junks as he wished by taking advantage of a low tide, when several Chinese boats ran aground in the mud, their bellies up just like ducks.

The changes which were soon approaching greatly affected the wartime junk in particular. According to Worcester, their disappearance was due to the Chinese purchasing gunboats from 1880 onwards. "As a result of this, the picturesque Chinese war junks disappeared forever, […]" concluded the British historian. 24

Landscape with Junks, Macau.

GEORGE CHINNERY.

Ca 1835-1840. Ink and sepia wash on paper. 28.0 cm x 20.0 cm.

Leal Senado / Luís de Camões Museum, Macao.

In: George Chinnery: Macau, [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado -Museu Luís de Camões, 1985, ill.37 (Collection Toyo Bunko - Tokyo).

2.7. AUDEMARD, THE FRENCHMAN

Landscape with Junks, Macau.

GEORGE CHINNERY.

Ca 1835-1840. Ink and sepia wash on paper. 28.0 cm x 20.0 cm.

Leal Senado / Luís de Camões Museum, Macao.

In: George Chinnery: Macau, [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado -Museu Luís de Camões, 1985, ill.37 (Collection Toyo Bunko - Tokyo).

2.7. AUDEMARD, THE FRENCHMAN

The wave of interest Pâris created continued discretely and unrecognised for a long time in the hands of a merchant marine officer, Louis Audemard. His career in the Far East spanned the years 1885 to 1910 during which period this French official was able to observe and study vessels from the countries where he was stationed 'de visu'. Born in 1865 in the south of France, Louis Audemard was a later source. Beginning from 1885, his observations in the Far East coincided with the time of publication in France of the monumental work by Pâris, now Vice Admiral, Souvenirs de Marine.25

On his return to France from the Far East, Louis Audemard conceived his book and moving to Brittany, the retired officer began writing his work devoted entirely to the Chinese junk.

The Second World War interrupted him and the work's publication ended up being finished only in the form of a series of articles for Rotterdamm's Maritime Museum in 1950, thanks to the interest shown in the subject of traditional vessels in the Far East by the museum's director, C. Noteboom, a Dutch anthropologist. The publication of Audemard's work in Portuguese by the Maritime Museum in Macau in 1994, opened the way for readers of this essential book to the study of large Chinese vessels from the past.

2.8. DONNELLY, THE ARTIST

Apart from Audemard's work, the first half of the twentieth century saw the beginning of different enterprises with Chinese junks as their theme which stand out.

The huge international exhibitions organised firstly in Saint Louis, USA, in 1904 then in Liege, Belgium in 1905, would take some European functionaries over to China to collect and send models of junks from various Chinese provinces. 26 Some Westerners holding posts in China were to make their own personal collections of junk models which are outstanding examples among the information available on these boats today. 27 Some even began making a business out of junk models in the 1920's. Among them appears the name of Ivon Donnelly, artist, enthusiast and scholar.

Min Jiang (Upper Yangzi River) - Kua Zi type passengers' junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part.5, estampa [ill.] 38, p.275.

Min Jiang (Upper Yangzi River) - Kua Zi type passengers' junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part.5, estampa [ill.] 38, p.275.

Jiujiang (Lower Yangzi River) - Passengers and commerce junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 6, estampa [ill.] 5, p.297.

Jiujiang (Lower Yangzi River) - Passengers and commerce junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 6, estampa [ill.] 5, p.297.

SHUI BAO JIA CHUAN 水保甲船 River Police Boats called "Fast Crabs" were recognizable by white & blue sails. It is recorded that 161 police boats were operation on the Yangtze river.

In: SOKOLOFF. Valentin A., Navios Da China/Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, 111.39.

SHUI BAO JIA CHUAN 水保甲船 River Police Boats called "Fast Crabs" were recognizable by white & blue sails. It is recorded that 161 police boats were operation on the Yangtze river.

In: SOKOLOFF. Valentin A., Navios Da China/Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, 111.39.

ZHIFU CHUAN 芝罘船 Chefoo Fishers operate in cold climates where they are subject to icing. Up to 1923 they were numerous in the Vladivostok area where I [The Author] sailed them sometimes.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, III. 13.

ZHIFU CHUAN 芝罘船 Chefoo Fishers operate in cold climates where they are subject to icing. Up to 1923 they were numerous in the Vladivostok area where I [The Author] sailed them sometimes.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, III. 13.

SHAOXING CHUAN 紹興船 SHAOHING-CH' UAN or HANGCHOW BAY TRADER, despite its fanciful decoration, is a very seaworthy & practical craft made to ride in the wake of "The Third Wonder of China" --The Hangchow Bore, which may go up to 30 feet high.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China. Macau. Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, 111.19.

SHAOXING CHUAN 紹興船 SHAOHING-CH' UAN or HANGCHOW BAY TRADER, despite its fanciful decoration, is a very seaworthy & practical craft made to ride in the wake of "The Third Wonder of China" --The Hangchow Bore, which may go up to 30 feet high.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China. Macau. Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, 111.19.

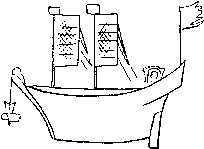

TUOCHUAN 拖船 This Houseboat drawing was copied from [a] Chinese 12-th century picture. [...] This boat most likely operated near Kaifeng. It was tracked up-stream by 5 or 6 men & travelled about 30 miles a day.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, I11.51.

TUOCHUAN 拖船 This Houseboat drawing was copied from [a] Chinese 12-th century picture. [...] This boat most likely operated near Kaifeng. It was tracked up-stream by 5 or 6 men & travelled about 30 miles a day.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China /Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, I11.51.

Donnelly's name is better known among junk lovers through a small book published in Shanghai in 1920 and later re-edited28 with what the author had originally illustrated in black and white drawings changed to colour. Donnelly is also the author of a small catalogue published in Shanghai around 1923 from which the general public was able to buy various, rather crude models of junks, proof that in this way a trend was forming among the public which was to grow bigger in time.

Donnelly also wrote specialised articles in which he examined in depth different aspects of the junk's history. 29 A little later D. W. Waters, another European of British descent, went back to investigate the subject of Chinese junks to which he dedicated several articles between 1938 and 1955. However the major British contribution on the subject of junks at this level was Worcester, a Shanghai clerk who was intimately familiar with vessels on the Yangzi river.

2.9. WORCESTER, A CUSTOMS OFFICER

Worcester's work, based on observing boats over several decades, had large Chinese river boats as its principle starting point then expanded to seafaring junks, thereby creating the basis for scientific research on junks. Worcester had the advantage of being assigned by his superiors to investigate the subject of traditional Chinese vessels. 31 Vessels from the Far East continued to fascinate both the erudite and aesthetic European observer. In 1945 a book entitled Jonques et Sampans (Junks and Sampans) was published in Paris. The book was illustrated entirely with original watercolours of Cochinchina and China in the 1920's. 32 Traditional marine construction in the Far East was in a process of complete transformation by then. 33 French colonial presence in Cochinchina took nautical ethnologists like Pierre Pâris to comprehensively study marine construction in Southeast Asia, including junks, noting their changes from place to place. One of the examples was double-masted vessels on the Red River that Pierre Paris saw disappear between the years 1924 and 1942 "[...] probably as a consequence of the spread of wire stays."34

Jean Poujade, another nautical ethnographer, became interested in traditional vessels from the Far East in even more detail, including Chinese junks. Poujade makes the connection between boats from the past and present. While writing on Chinese junks from Siam, the ethnographer noted a similarity in a bas relief from the twelfth century in Angkor, Cambodia, which showed a vessel very similar to contemporary junks in the region. 35

Furthermore Poujade gave some hints on disentangling the labyrinth of influences inflicted over the centuries in Southeast Asia. In an account full of ideas, he suggests, for example, that the modifications in the vessels' sails could have reflected a more or less 'peaceful' colonisation. 36

Analysing such conclusions today reflect the strong influence of theories in force since then. Half a century ago it was fashionable to try to establish connections and relationships between distant parts of the world. The most recent scientific developments in the human sciences have come to disfavour this view of 'dissemination', leaving room for the possibility of independent inventions. 37

Distanced for the most part from outside influences, the junk seems then and even today to appear like a floating laboratory in which Chinese boat builders explored various possibilities. 38

Design of a junk.

Twelfth century. Transfer from a low relief from the temple of Bayon. in Angkor.

The texture of the hemp sails is visible, as is the axial rudder at the prow.

In: POUJADE, Jean. La Route des Indes et ses Navires, Paris, 1946. I11. p.257.

Design of a junk.

Twelfth century. Transfer from a low relief from the temple of Bayon. in Angkor.

The texture of the hemp sails is visible, as is the axial rudder at the prow.

In: POUJADE, Jean. La Route des Indes et ses Navires, Paris, 1946. I11. p.257.

§3. THE LABYRINTH

3.1. BEAUTY AND CONFUSION IN THE WESTERN VISION OF THE CHINESE JUNK

"Apart from ocean going junks as a separate class, junks differ from each other depending on their mode of construction and design, [...]" observed Worcester. "Individual types of junk are remarkably similar." The British expert later adds: "With the exception of the area of Hong Kong, where probably due to foreign contact and influences, there are no two junks alike."39 Poujade states that: "[...] and the hundreds that could have been classified as different types (of Chinese junks) and their variations; could perhaps reach the thousands. Each province and river sector, each port, has not only its own type.".40

3.2. POINTS IN COMMON

Confronted with such a diversity of designs, Poujade distinguished an underlying thread in all Chinese marine construction:

1. "The maximum width of the keel is found behind the middle of the boat's hull, [and]

2. the sails are semi-rigid and have "the most efficient performance in the world."

For the layman, the first characteristic could appear as a very technical detail but for the The distinguishing traits of the Chinese junk may be found in a geographical area which extends to part of Southeast Asia. The Singapore Straits marked the limit of the influence of typical junk sails. The international port of Malacca, situated in the vicinity of the straits, played a key role in marking the gateway to the seas of the Far East for navigators in the Indian Ocean. This role of exclusive 'gateway' for merchants, was equally one for sailors and vessels.

Shandong Chuan -- Plan.

Comercial junk from Fujian to Shandong.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 22, p.462.

Shandong Chuan -- Plan.

Comercial junk from Fujian to Shandong.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 22, p.462.

Fishing junk of the Sanmen Bay -- Plan.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 82, p.507.

Fishing junk of the Sanmen Bay -- Plan.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 82, p.507.

Sampan for passengers.

Sampan of the Fuzhou type, with sails and oars.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 58, p.487.

Sampan for passengers.

Sampan of the Fuzhou type, with sails and oars.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 58, p.487.

3.5. ORIGINS: THE ASIAN CRADLE

Because of its size, China has a very extensive coast dotted with nearby Islands. Other Islands, far more out to sea in the north and south, indicate China's sea limits, extending in the southeast almost without interrupted until Australia and the Pacific ports.

Recent studies by ancient historians have shown that this world of Islands in the Far East at the gateway of China's sea borders was the nucleus, cradle and laboratory of the first stages of navigational history. In the middle of China's Neolithic Period, men left the continent in order to reach these Islands to the south-east. Later, around 1600BC, during the time of the Bronze Age in the West, descendants of pioneers who had settled on them, set out in the direction of the South Pacific.

It is not known what vessels were used for these ocean crossings, although it has been considered that they were canoes which somehow predated the Polynesians' ocean-going canoes that appeared later.

Yet in even earlier prehistory, five thousand years ago, other men from the south of the great Asian archipelago reached the Australian continent crossing dozens of kilometres of ocean. With what vessels? Among the possible answers, the Chinese nautical world presents a very ancient technical solution which traces itself back to the roots of nautical technology in China and which curiously also has to do directly with the history of junks: rafts.

3.6. RAFTS VERSUS CANOES AND DUGOUT CANOES WITH FLOATS

Experts concluded decisively: while the monoxlye canoe, dug out of a single log, formed the basis of the most commonly used boats in the Pacific and in various places in the Indian Ocean, having gradually evolved until becoming the hull of wooden ships, with an independent keel and broadside, this very canoe was considered for a long time as foreign to Chinese nautical technology which had recognised the raft in its place. G. R. G. Worcester quoted a declaration attributed to the Emperor Huangdi (around 2697BC) according to which "[...] boats were built by digging out tree trunks [but confirmed on the other hand that] canoes dug out of tree trunks are not found in the Chinese continent today."42

Chinese junk from Singapore.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 8, estampa [ill.] 31, p.429.

Chinese junk from Singapore.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 8, estampa [ill.] 31, p.429.

Saigon sea junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 10, estampa [ill.] 27, p.546.

Saigon sea junk.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 10, estampa [ill.] 27, p.546.

Chinese merchant junk from the Malacca Strait.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 8, estampa [ill.] 44-right, p.433.

Chinese merchant junk from the Malacca Strait.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 8, estampa [ill.] 44-right, p.433.

In the light of different archaeological discoveries, this view is contested today by modern Chinese, Japanese and Korean research. 43

In denying the existence of the monoxyle (dug out) canoe in the ancient world of Chinese nautical history, Worcester proposed that the raft was the key to the uniqueness of the Chinese navy. Throughout the centuries the raft, forerunner of all vessels, was man's technical solution for circumnavigating the vast expanse of China's internal waters, lakes and rivers.

It was in the tenth century, thanks to regional and commercial autonomy, that around fifty thousand kilometres of a huge network of inland waterways began being intensely exploited. 44

Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, huge cargo rafts circumnavigated these inland waters in China to transport people and merchandise. Poujade reproduced a drawing of one of them on the Ya river, a tributary of the Yangzi (see the illustrations) side by side with a drawing of a junk from the Yangzi. The smooth lines of the bottom of many junks caused the amazement of a number western observers. The comparison between the dimensions of the hull on junks and the very raft used in China's internal waterways is a subject repeatedly taken up among those studying junks. A study of the ancient monoxlye canoes found in Chinese waters prompted an entire reanalysis of this question.

Judging the attributes of an ancestral raft, Worcester summed up the stages in the construction of a Chinese boat in the following way: "The methods used in the construction of junks vary according to the place, size and type of junk, but essentially the initial stage consisted in fitting the straight planks for the bottom either side of the floor, above a central keel (when one is put in) and joining them together, that is to say that these planks are fixed together by means of iron nails beaten into a shape with tips at both ends [...]."45

Techniques of this type come from the very distant past in which the marine boat builder, before the use of iron nails, fitted round or flat dowels which, running through the thickness of each plank allowed, thanks to a rather complex system of coupling together, a homogeneous combination in the absence of interior compartments, which consisted of the classical transversal structure of western boats. 46 Such techniques were used by marine boat builders since the Bronze Age in the West and are, as a result, the last evolution of a process which began with the monoxyle canoe enlarged little by little in size and length, as long as the initial size of the trunk never reached the capacity of the finished vessel. In any case we are further on than rafts.

3.7. RIVER AND SEA JUNKS

The expanse of China's waterways warranted the use of the enormous fleet described on several occasions by European observers travelling in the area. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries these European travellers could watch the thousands of 'Imperial junks' sailing along the canals and rivers bringing the taxes from various provinces to the court in Beijing.

In such circumstances, the relative importance of river junks in the reports confined to Chinese junks 'tout court' demanded a more cautious appraisal on the part of researchers.

TOP: Raft in the Ya River, a tributary of the Lower Yangzi River.

BOTTOM: Junk in the Yangzi River.

It is noticeable the presence of raft forms in the architecture of junks.

In: POUJADE, Jean, La Route des Indes et ses Navires, Paris, 1946, ills. 46-47.

TOP: Raft in the Ya River, a tributary of the Lower Yangzi River.

BOTTOM: Junk in the Yangzi River.

It is noticeable the presence of raft forms in the architecture of junks.

In: POUJADE, Jean, La Route des Indes et ses Navires, Paris, 1946, ills. 46-47.

The distinction between river and sea junks is even more difficult. So much so that, in certain cases, a tradition of nautical construction adapted to a river environment was also used in vessels for maritime trade routes. Audemard often touched on the subject of the 'Sha Chuan', the large sea junks used to carry merchandise. "They have a smooth bottom because their stopovers, dotting the coast north of Jiangsu, were comprised of various sand banks from where the name 'sand boats' originated."47

The nautical ethnographer, Jean Poujade, noted in describing a similar situation from the middle of the twentieth century:"[...] the majority of sea junks are flat bottomed [...]."48

A short time earlier a British writer summed up in these words:

"Chinese junks are flat bottomed vessels and the majority reach around one thousand tons [...]."49

The first archaeological discoveries carried out in the second half of the twentieth century revealed another aspect of seafaring junks where the shape of the bottom, far from being flat, was in quite a distinct "V" shape. This discovery revealed the regional differences in Chinese junk construction.

3.8. GEOGRAPHICAL COMPARISON: JUNKS FROM THE NORTH AND SOUTH

The junks' diverse shapes follow a nautical criteria by varying from region to region. Two areas on the Chinese coast can be delineated: the northern coast, traditionally the more isolated where there are mostly shallow waters, and the southern coast where deep waters abound and where contact with the outside world had always been more frequent.

These two opposing regions are distinct and are reflected in the shape of the hulls, the flat bottoms and even prows characterising northern coastal junks where as tapered prows are sea guaged, a more important characteristic of southern junks.

3.9. FOREIGN INFLUENCES: THE ARABS'ROLE

Junks in the south became a more complicated story because of frequent contact with foreigners. For this reason the respective influences between the Muslim ships coming from the Indian Ocean for more than one thousand years and South Chinese coastal vessels have been often discussed. The 'eye detail' at the prow of Chinese vessels was, for Louis Audemard, the result of an Arab influence with its roots in Ancient Egypt. Ivon Donnelly had already noted that the only junk from the Golf of Bei Zhili, on the Chinese coast, to have an eye painted on its hull was the junk which did the trade route between the ports of Jiaozhou and Tai Pouto. 50

Jiazhou had actually been an important Arab trading post in the first century. 51

Within this context, the question of influences affecting boat construction was even more complicated with the fact that they varied according to each particular part of the ship. According to Poujade, by exporting technology in Siam, Chinese sailors easily adopted local designs for the hull but not for the sails, which preserved its original characteristics. There was nothing better than sails to distinguish an Arab vessel from a junk.

3.9. SAILS

When Ibn Battuta observed a group of Chinese junks which had sunk in Calcutta, India, between 1341 and 1342, the Muslim explorer noted that the sail "[...] is of bamboo, stitched like a mat."52 He kept longing to see the sails up as these vessels were submerged.

Upper Yangzi River junk under construction.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 32, p.84.

Upper Yangzi River junk under construction.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 32, p.84.

Bei Zhili junk -- transversal section.

Sha Chuan section of the hull's watertight compartements.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 33, fig. I, p.86.

Bei Zhili junk -- transversal section.

Sha Chuan section of the hull's watertight compartements.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 33, fig. I, p.86.

Bei Zhili junk -- different types of carcass joinery.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 33, figs. 2-6, p.86.

Bei Zhili junk -- different types of carcass joinery.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 33, figs. 2-6, p.86.

Part of a central piece from a vessel dating from the second half of the eleventh century found in Korea (Wando Island).

In: ZAE-GEUN, Kim, The Wreck Excavated for the Wando Island, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, Shanghai, 4-8 Dec. 1991 -- [Proceedings of...], Shanghai, Society of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, 1991, pp.56-58.

Part of a central piece from a vessel dating from the second half of the eleventh century found in Korea (Wando Island).

In: ZAE-GEUN, Kim, The Wreck Excavated for the Wando Island, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, Shanghai, 4-8 Dec. 1991 -- [Proceedings of...], Shanghai, Society of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, 1991, pp.56-58.

Later, the rigging on junks would cause still greater admiration when European sailors had the opportunity to watch the ease with which a Chinese sailing vessel could change tack "[...] almost without many hands on deck [...]."

But because of its weight, which included the 'fabric', (stitched later) and the booms of wood or bamboo, the junks' sails required a great effort from the crew when hoisting them up. On the other hand, this very weight make the manoeuvre of dropping the sails quick and easy, a capacity which on more than one occasion left European sailors in awe. Their traditional square sails, developed and improved on since Antiquity, needed complicated manoeuvres when being brought in.

The even distribution of pressure along the mast on a junk allowed the mast to not need the support of 'back stays' but of a kind of immense, smooth, exposed pillar from where the sail unfolded. Modern aerodynamic studies allow one to appreciate how a junk's sails, semi-rigid due to the horizontal net of straight poles which supported and veered the sails (hemp or fabric) like a 'wing' which could be controlled from the side.

The variety of shapes seen for junk's hull also holds true for the structure of sails.

On seeing a junk's rigging in the first half of the twentieth century, Worcester reported a progression from south to north: the transversal beams began to appear on the coast of Annam and Tonkim. In Guandong where they are fewer in number, they had four to six poles per sail. On the Yangzi estuary, the number reached twenty six, however certain sails from the Yangzi have up to forty. But in the north junks have sails with twenty to thirty but, warns Worcester, it would be "[...] dangerous to be dogmatic on this point."54

3.10. RUDDERS

The axial rudder such as we know on boats today already existed in China more than half a century before it appeared in Europe at the end of the twelfth century. Apart from its ancient origin, what makes the Chinese junk's rudder of special interest is how adaptable and diverse it is. The first attribute is its mobility: as opposed to the fixed axial rudder around a rotational axis parallel to the stern poop of the vessel, the Chinese rudder can in many cases be brought up to sail in very shallow waters.

The same rudder can also be placed in a low position, forming an overhang underneath the hull. Once again, the work of modern hydrodynamics shows how such a position, which places the rudder blade further away from interferences caused by the water flow in the back part of the hull, increases the efficiency of the rudder's blade, principally for the speed of the bowline where the surface area contributes to diminishing lateral roll. Maximum efficiency of a rudder is demonstrated by the Fujian junk where the rudder's blade reaches proportions in length and breadth which equal the highest proportions seen in modern competition yachts -- long main keel and narrow rudders. 55

Another shape of 'modern' rudder is the 'composite' rudder common in river junks, in which the rudder's blade is divided into two parts on each side of a central tiller. Used in North American vessels in the last century, this design alleviates the effort a helmsman has to exert to control the vessel's course.

3.11. WATERTIGHT COMPARTMENTS

According to the British sinologue, Joseph Needham, the Chinese junk seemed like a long, open piece of bamboo. 56 In this way the bulkheads or cross divisions of wood which separate the hold of the vessel into watertight compartments showed a logic inherent in the very shape of bamboo, unsinkable thanks to its several self-contained sections. 57 Many Westerner observers, beginning with Marco Polo, became interested in this characteristic of Chinese hulls.

At the end of the eighteenth century the North American, Benjamin Franklin, reported on the virtues of the Chinese example in having watertight compartments in the hull as of eventual use in the west. Zheng He

Sails of Guangdong River junks.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part.2, estampa [ill.] 45, p. 106.

Sails of Guangdong sea junks.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 44, p.105.

Sails of Fujian sea junks.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau. 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 46, p.107.

3.12. CAULKING

Worcester described a Chinese marine carpenter's work as skilled but without attention to detail. 58 A whitewash called 'chunam' made of chalk and wood oils remedied any eventual defects in the finishing stage of caulking. An abundance of marine shellfish on the southern coast of China led boat builders to using a chalk made from these very shells, the larger ones making a purer chalk. 59 The use of oil based and chalk based pastes was a characteristic of all Asian ocean going vessels. Once again this practice was praised by European sailors who saw in some cases that the coat of paint obtained in this fashion was hardened to the point of becoming the exterior coat of the hull's compartments, thereby protecting the interior woodwork. The detailed examination of the remains of a junk from the Song period found at the port of Hou-Zhu, in the bay of Quanzhou, in the Fujian province in 1974, allowed the verification of the way boat builders in ancient times even used such a paint 'chunam' to protect iron nails from corrosion. 60

3.13. GIANT JUNKS

Chinese boat building had other characteristics which set it apart from the western world. The large stem oar of the Chinese was frequently remarked on and this "sculling oar" according to an account by Ibn Battuta observing Chinese junks at Calcutta's port, India in 1341 to 1342, called for another sort of comment. "[...] the oars [writes the Muslim traveller] are as large as masts and [...] are manoeuvered by ten to fifteen men per oar. The rowers stand to operate the oars [...]." 61

Perhaps the most controversial trait and even more mysterious today in the history of Chinese junks is said to be regarding the vessels built at the beginning of the fifteenth century for the journey of the eunuch Admiral Zheng He to the Indian Ocean. The discussion revolves around the measurements used in descriptions where there appears the dimension of four hundred and forty four chi. The size of a chi varies between twenty-five to thirty-five centimetres (Ming gong bu chi) and thirty-three to eighty-five centimetres (Huai chi) in the building of large junks from the province of Jiangsu. A recent study carried out by contemporary Chinese researchers who are interested in the actual construction of Zheng He's fleet, indicate the measurement as having the value of 26.74, to 28.03 centimetres around the Fujian province and that would make the ships a length of around one hundred and thirty metres. 62

Chinese junk.

Displayed on a Catalan portulan (1375), adjacent to the southern coast of Asia.

In: PÂRIS, H.-L., De la Préhistoire à la Fin du Moyen-Age, in "Histoire Universelle des Explorations", Paris, 1957.

Given the larger chi value, 63 it would make Zheng He's junks the biggest wooden ships in mankind's history but many western historians have opted for much lower dimensions, allowing a length of approximately seventy metres, yet others spoke of three hundred feet (ninety metres). The voyage of the Keying from 1846-1848 and the accounts from the Chinese crew give us some points for comparison. This is still open to debate.

According to Chinese technical experts from the middle of the nineteenth century in the Guangdong region, the junk Keying, with around eight hundred tons of displacement, was a second category ship by Chinese standards. The largest junks in that case from this region would have had around one thousand tones of displacement. 64

Once again the technical and cultural barrier which separates the eastern and western worlds limits the debate here: according to the techniques of boat building in use in the west since classical Antiquity, wooden seafaring ships with a length of over one hundred metres would reach or surpass the limits considered possible by nautical engineering. We know that prestigious vessels with a length of around one hundred metres were built in ancient times on the Mediterranean. A ship like this with a length of one hundred metres and a width of twenty metres was found in this century underneath the floodgate of an ancient lighthouse at the port of Ostia, near Rome. 65

Other vessels of the same category existed in Antiquity but their lives were always short lived, limited mainly to just ceremonial demonstrations.

For a long, efficient voyage on the high seas, the limit allowed was around seventy-five metres in length for boats made only of wood, as in the case of some of the most recent big sailing ships in the West. 66

These considerations of nautical engineering, which cannot be disputed, are based however on concepts of boat building which have little in common with the building processes actually used by the boat builders of Zheng He's fleet. Western vessels made of wood, small or large, always use a transversal structure erected over the keel, without partitions like the Chinese bulkheads.

The resulting rigidity, in one case or other, could be varied in a considerable way making it possible in one instance and impractical in another.

Be that as it may, the gigantic junks of Zheng He, six centuries after having left the waters of the Yangzi estuary, do not stop sailing in the imagination of those who have somehow heard of their existence.

§4. THE JUNK TODAY

4.1. CHINA IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Various phenomena of the nineteenth century intrinsically altered the Chinese junk's history: the throng of Europeans arriving with all the implications equally at a political, military and commercial level, the introduction of motor power, the end of war junks at the end of that century.

A big junk in Guangzhou.

Drawing. Late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

In: LAING. Alexander, The American Heritage History of Seafaring America, New York, American Heritage Company, 1974. p.92.

Even so in the first half of the twentieth century, some large five masted junks survived but Japanese military and economic occupation soon saw their disappearance. Yet the impact of motorisation was not the same in every region.

4.2. INDUSTRIALISATION AND GEOGRAPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

For the North American military observers after the war, the presence of Chinese traditional junks in the fishing industry in Communist China was one of the yardsticks for evaluating the country's economic growth. Around 1960, the People's Republic of China counted approximately three hundred and sixty thousand junks with a cargo capacity totalling around three thousand tons. This enormous fleet still represented between sixty to seventy per cent of the total of China's internal trade using waterways. 67

According to one source in 1949, at the beginning of the Communists coming to power, China had a total of sixty motorised fishing junks. In 1960, fishing communities had approximately two hundred thousand fishing junks, sailing ones mostly whose fishing limit was to about twenty miles from the coast. 68

The junk was still a topic for debate among North American military analysts when in the 1960's a project often mentioned was the landing of forces from the People's Republic of China on the Island of Taiwan, transported by a huge fleet of junks gathered together for the manoeuvre. In 1967, the logistical difficulties of such a project made foreign experts give little credit to the subject. 69

Such debates are nothing new in Chinese nautical history. The British oriental expert Charles Ralph Boxer quotes the account of a seventeenth century Jesuit, Martino Martini and according to him the inhabitants of Fujian Province, at some stage, intended facilitating an invasion of Japan with the help of a bridge built of ships. 70 In the sixteenth century the missionary Gaspar da Cruz recorded: "To show the grandeur of their kingdom, the Chinese have a popular saying according to which the King of China could make a bridge of boats from China to Malacca, a distance of almost five hundred leagues, which in spite of not seeming possible, still however metaphorically indicated the Chinese concept of grandeur, and the huge number of vessels which the country could amass."71

As far as archaeology goes, the development of underwater investigation in the second half on the twentieth century and the simultaneous development of marine technology, brought about the discovery and study of several junks' hulls in the last two decades.

4.3. UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY

The extent of bibliography available at the moment, commented on at the beginning of this article, lead archaeologists to give particular emphasis to some subjects like the flat bottom and the lack of keel in junks or the watertight compartments in the hull. However the sea had kept some surprises.

One of them was the continual presence of a main keel and sections of the hull in "V" shape, the case in all archaeological sites seen at that time. 72

This type of evidence seems to contradict the facts from written accounts. A more detailed discussion shows that in reality archaeological sites correspond mainly to junks from the southern coast of China where the tradition is far from that of flat-bottomed junks and where the presence of a keel and of lower sections is known. One example was a junk excavated in Shinan, Korea. The archaeologist, Zu Guen Kim, interpreted the "V" shaped bottom and the keel of the vessel as being the remains of a traditional southern Chinese boat which was very different to the boat building traditions of Korea where flat-bottomed hulls were prevalent. 73

Another question raised by underwater excavations was the exact function of the 'watertight' bulkheads.

Holes for the circulation of water in the lower part of the bulkheads were found in in a vessel from Quanzhou, and in other archaeological remains investigated in Thailand as in Sumatra. 74

Some sources prior to this, among them Worcester, made reference to the deliberate flooding of watertight compartments in the junks' hold to balance their movement in the water.

These and other questions will be examined in their turn in the discussion on future excavations and after a more in depth confrontation between written accounts and archaeological evidence.

4.4. THE LA DAME OF CANTON

In the meantime, the tradition is disappearing so quickly that when, at the beginning of the 1980's, a French association backed by the French Oil Company Elf-Aquitaine wanted to commission the building of a traditional junk in Guangzhou christened La Dame of Canton, it was designed and measured by Chinese naval engineers from a large Guangdongnese naval shipyard. Lacking French representatives for the project they found local experts in traditional construction.

Whatever is the real value of the La Dame de Canton experience, it already remains clear that the end of the twentieth century constitutes the final stage for the history of traditional junks and the collection of first hand accounts from the participators, sailors and boat builders.

Of the gigantic junk of wood and bamboo that the British from the frigate Blossom saw and drew in Luozhou in 1827, all that remains for us now is a piece of paper, an image, and a dream. This is the first step.

The second step could be to one day have a three dimensional reproduction of the giant junk, an archaeological model, an attempt from our times of producing a model of a Chinese sailing vessel from their times, a virtual junk.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce

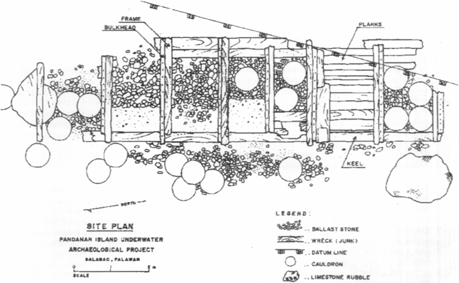

Plan of the remains of a junk excavated south of Palawan Island.

Excavations by Ecofarm (Manila), Gilbert Fournier, excavation director.

NOTES

1 Luozhou became a Japanese possession from 1895, renamed Okinawa.

2 Les tours du monde des explorateurs: Les grandes voyages maritimes, 1764-1843, Paris, Jacques Brosse, 1983, p. 167 -- Engraving by E. F. Finden according to a drawing by William Smyth: "A huge junk left the port surrounded by a great number of boats. It was decorated with flags a all types and every size [...]. It was the junk which annually transported Luozhou's taxes to Fujian.'").

3 VILLAIN-GANDOSSI, Charles, Le navire médiéval á travers les Miniatures, Paris, CNRD, 1985, pp.38-40. Charles Villain-Gandossi, an expert in mediaeval naval iconography, placed the use of the axial rudder to the middle of the thirteenth century, which gradually disappeared in the iconography which followed. This author speaks, however, of a slow abandoning of the technique from before side rudders. In one case, an drawing from the fifteenth century showed a double configuration on the same boat: axial rudder and side rudders.

4 BATTUTA, Ibn, Voyages et périples, in P. CHARLES-DOMINIQUE, P. ed., "Voyageurs arabes", Paris, Bibliothéque de la Pléiade, 1995, p.914

Louis Audemard said before that the city of "Zeitoum" corresponded to Fuzhou· according to some and Xiaman· according to others. Sîn-Kalân ("Syn-Cafan" for Audemard) is Guangzhou.

See: AUDEMARD Louis, Juncos chineses, Macau, 1994, Museu Marítimo, chapter "Marinha Chinesa antigajuncos de comércio" [2nd edition - Portuguese edition].

5 MOTA, A. Teixeira da - FARIA, F. Leite de, Novidades náuticas e ultramarinas numa informaçao dada em Veneza em 1517, Offprint of the Centro de Estudos de Historia e Cartografia Antiga da Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar, (99) 1977, p.56

6 Idem.

7 FONSECA, Quirino da, A Caravela Portuguesa, Lisboa, [p. n. n.], [n. d.], part 2, p.30

8 BOXER, Charles Ralph, ed., South China in the sixteenth century being the narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O. P., Fr. Martin de Rada, O. E. S. A. (1550-1575), London, Hakluyt Society, 1953 p.112, note 3--"[...] to the number of millions."

9 Ibidem., pp.63-64 -- The author give us some examples of different accounts from missionaries about voyages on board junks.

10 T'IEN Ju Kang, Apogeu e declínio de junco chinês: mercadores, empresários e cules: 1600-1850, in SEMINÁRIO CIÊNCIA NÁUTICA E TÉCNICAS DE NAVEGAÇÃO NOS SÉCULOS XV E XVI (SEMINARY ON NAUTICAL SCIENCE AND NAVIGATION TECHNIQUES DURING THE FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURIES) - [Actas do...],

Instituto Cultural de Macau - Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1988, p.32

11 DONELLY, Ivon A., Chinese Junks and Other Native Crafts, Singapore, 1988, p.4.

12 PRICHETT, R. T., Pen and Pencil Sketches of Shipping and Craft all Round the World, London, 1899, p. 162 -- At the end of the nineteenth century, the author travelled in the Far East where he saw the development of different types of Chinese junks. He refered condescendingly to the voyage of the junk Keying to England, which took place from 1846 to 1848, with the following words: "The marvel was that she ever got here."

13 AUDEMARD, Louis, op. cit., p. 183. T'IEN Ju Kang, op. cit., p.36 -- The author says that in 1849 China "[...] possessed two hundred and ninety five junks with a tonnage which rounded up to eighty six thousand two hundred [...]."

14 POUJADE, Jean, La route des Indes et ses Navires, Paris, Payot, 1946, p.243 -- "L'examen détaillé d'une jonque de guerre donnera l'idée des anomalies des constructions chinoises [...]. " ("the close scrutinty of a war junk will throw some light on the anomalies of Chinese engineering [...]."

15 Ibidem., 1946, p.245; apud PÂRIS, L.-H., De la Préhistoire à la Fin du Moyen-Age, in "Histoire Universelle des Explorations", Paris, 1957. DARS, Jacques, La marine chinoise du Xe siècle au XVIe siècle, Paris, 1992, p. 113 -- The author recalls an original Chinese source, the Guangdong xinyu, · speaking specifically of boats in the shape of ducks ("canes") in the Guangdong province.

16 Idem.

17 WORCESTER, G. R. G., Sail and Sweep in China, London, 1966, p.8, note.

18 Perhaps it was the Keying to which Pritchett referred to in a passage from his book edited in 1899. PRITCHETT, R. T., op. cit., p. 162 -- "One of these huge Tien-Sien monsters came over to this country for the Great Exhibition of 1851, and lay in the West India Docks [in London]."

19 A Description of the Chinese Junk 'Keying': Printed for the Author, and Sold on Board the Junk, London, 1848, p.15

20 AUDEMARD, Jean, op. cit. -- After two hundred and twelve days at sea and a stopover on St. Helena Island on the 17th of April of the same year.

21 The role H.-L. Pâris played was such that even today, modern works use him to illustrate or reconstruct boats which have disappeared. SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios da China / Ships of China, Museu Marítimo de Macau - Fundação Oriente, 1990 -- This contemporary author, artist and observer, who lived in the Far East in the first part of the twentieth century, resorted to a picture of a junk published by Pâris a century earlier to present a colour version of the same boat in a work published in 1982 and reedited, this time in English and in Portuguese in Macao in 1990.

22 T'IEN Ju Kang, op. cit., p.37

23 POUJADE, Jean, op. cit., p.244 -- "[...] il est bien rare qu'un voyageur trouve un navire dans des conditions qui lui permettent d'en mesurer les parties immergées [...]." ("[...] for a traveller, it is extremely rare to find a boat in circumstances that enable the measurement of the [usually] submerged sections [...]."; apud PÂRIS, L.-H., op. cit.

24 WORCESTER, G. R. G., op. cit., p. 11, note.

25 PÂRIS. L-H., Souvenirs de Marine, Paris, 1889, partie [section] IV, planches [plates] 181-240 -- In this section of the book the author reproduced in great detail the design of a Chinese junk seen in 1885 on the Island of Hainan by "Monsieur Henrique" captain of the frigate.

26 JOHNSON, W., ed., Shaky ships. The formal richness of Chinese shipbuilding, Antwerp, Nationaal Scheepvaartmuseum, 1993 [Exhibition Catalogue]-- An exposition devoted to models of Chinese junks curated by the Belgium E. D. Johnson, shown in the National Maritime Museum of Antwerp with collections sent from China at the beginning of the twentieth century.

27 Collection of models of Chinese junks gathered by Frederick Maze, offered by him to the Science Museum of London, studied and published later by G. R. G. Worcester. Another collection on the same subject was gathered by the north American geographer, Spencer, and offered to the University of Texas and published by the author in that university in 1976.

28 DONELLY, Ivon Arthur, Chinese Junks and Other Native Crafts, Shanghai, 1924 [re-edited: Singapore, Graham Brash, 1988].

29 DONELLY, Ivon Arthur, Foochow Pole Junks, in "Mariner's Mirror", 9 (8) 1923, pp.226-231; DONELLY, Ivon Arthur, River Craft of the Yangzekiang, in "Mariner's Mirror", 10 (1) 1924, pp.4-16; DONELLY, Ivon Arthur, The 'Oculus' in Chinese Craft, in "Mariner's Mirror", 12 (30) 1926, p.339.

30 WATERS, D. W., The Chinese Yuloh, in "Mariner's Mirror", 32 (3) 1946, p.189; WATERS, D. W., The Straight and Other Chinese Yulohs, in "Mariner's Mirror", 41 (1) 1955, pp.60-61.

31 The initiative of this detachment was seen by Frederick Maze, the Chinese Marine Customs director. A great enthusiast of junks, Maze was far from being the only European in the East to succumb to the seduction of the local vessels.

32 FARRÈRE, Claude (text) - FOUQUERAY, Charles (drawings), Jonques et Sampans, Paris, 1945.

33 WORCESTER, G. R. G. Worcester, A Classification of the Principle Chinese Sea-going Junks (South of the Yangzi), Shanghai, Shanghai Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs, 1948. p. XIII -- According to the author the motorisation of Chinese junks took place from 1940 to break the Japanese line of defence.

34 PÂRIS, Pierre, Esquisse d'une ethnographie navale des peuples annamites, in "Bulletin des Amis du Vieux Hué", (14) Oct.-Dec. 1942 [2nd edition: Rotterdam, 1955 -- 84 pages 226 photographs].

35 POUJADE, Jean, Les Jonques des Chinois du Siam. in "Documents d'Ethnographie Navale", Paris, fascicle 1, 1946, p.16.

36 POUJADE, Jean, La route des Indes et ses navires, Paris, 1946, p.243, note 2 -- English translation: "We have to take into account, when we see a foreign sailing vessel little defined within an ethnic group, of a possible partial colonisation. Foreign sails, on the contrary are deeply rooted and overthrew ancient sails, therefore we are confronted with total ancient domination: and a generality."

37 MACKENZIE, D. A., China and Japan, London, Reed, 1995 -- The author, who was closely interested in the subject of the origins of Chinese culture, asked in a characteristic way: "Could it be that we can accept the following theory that in isolated parts of the globe communities were evolving by natural laws towards development adapted to their environment and that once achieved separate communities sprung up (some out of others) developing along similar lines?"

The date of the original edition, not cited here, appears to be at the end of the nineteenth century.

38 See: Note 26.

39 WORCESTER, G. R. G., 1966, op. cit., p.16

40 POUJADE, Jean, 1946, op. tit., p.242

41 GUTELLE, Pierre, Architecture du voilier, 2 vols., Paris, 1979, vol.1 "Théorie", p.116-117

42 WORCESTER, G. R, G., Four Small Crafts of T'ai-Wan, in "Mariner's Mirror", 4 (42) 1956, p.310. WORCESTER, G. R. G., Sail and Sweep in China". London, 1966, p. 1 -- The author brings up the same conclusion in referring to the role of the monoxyle canoe (dugout) in countries like Burma, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, concluding the following: "[...] there are no dugouts to be seen in China."

43 DEGUCHI, Akiko, Dugouts of Japan: Hull Structure, Construction and Propulsion, in: INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, Shanghai, 4-8 Dec. 1991- [Proceedings of...], Shanghai, Shanghai Society of Naval Architecture & Marine Engineering, 1991. Thanks to John Moffett from the Needham Research Centre, Cambridge, U. K., which made this document available.

Also see: DAI Kaiyuan, Notes on the Origination of Ancient Chinese Junks Based Upon Study of Unearthed Dugout Canoes, in "Marine Research", Shanghai, (1) 1985, pp.4-17 -- An important work on the monoxylous canoes of China.

44 DARS, Jacques, op. cit., p. 135

45 WORCESTER, G. R. G., 1966, op. cit., p.8

46 Here we will not go into these questions in detail as they go beyond the bounds of this article. However, we can point out that the question is more complex in traditional wooden construction in the Far East than in China, Korea and Japan, who used wooden cross beams in their traditional boats which joined with the sidebeams, in the absence of bulkheads like the Chinese.

See: ZAE-Geun kim, The Wreck Excavated for the Wando Island, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, Shanghai, 4-8 Dec. 1991-[Proceedings of...], Shanghai, Shanghai Society of Naval Architecture & Marine Engineering, 1991, pp.56-58; GREEN, Jeremy, The Shinan Excavation, Korea: An Interim Report on Hull Structure, in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 12 (4) 1983, pp.296-301 --For a more detailed view see the accounts of Zae-Geun Kim.

47 AUDEMARD, Louis, op. cit., p. 184

48 POUJADE, Jean, 1946, op. cit., p.249

49 MACKENZIE, Donald A., op. cit., p.25.

50 DONELLY, Ivon Arthur, op. cit., p.4; apud AUDEMARD, Louis, op. cit., p. 132.

51 In the thirteenth century the previous tendency was reversed and Chinese vessels dominated trade in the Indian Ocean.

See: LEVATHES, Louise, Les navigateurs de l'Empire Céleste, Paris, 1995, p.53.

52 POUJADE, Jean, 1946, op. cit., p.243 -- "[...] notre théorie; les Chinois allant s'établir á l'étranger adoptent les coques locales mais les gréent de la voile nationale; cet exemple de la jonque des Chinois du Siam est le corollaire de la lorcha portugaise: les constructeurs étrangers ont apporté la coque en Chine, les Chinois ont remplacé la voilure occidentale par la leur."

53 BATTUTA, Ibn. Battuta, op. cit., p.914.

54 WORCESTER, G. R. G., 1966, op. cit., 1966, pp.18-19.

55 See attached drawings. Designs of a Fujian junk's rudder system by Audemard, and shapes of keels experimented in the Davidson Laboratory by P. de Saix and the comparable efficiency in a yacht's centreboard speed.

56 Apud DARS, Jacques, op. cit., p.113

57 LEVATHES, Louise, op. cit., p. 102 -- The author brings up the idea of Needham's according to whom the watertight divisions in the hold of a junk were inspired by the structure of bamboo.

Zheng He

58 WORCESTER, G. R. G., 1966, op. cit., p.8 -- "[...] of the crudest."

59 LI Guo-Qing, Archaeological evidence for the use of 'chu-nam' on the 13th century Quanzhou ship, Fujian province, China, in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 18 (4) 1989, pp. 281-282

60 Ibidem., p.282

61 BATTUTA, Ibn, op. cit., p.914

62 LEVATHES, Louise Levathes, op. cit., p.100. The author, who directly contacted Chinese investigators who had studied the subject, quotes the following sources on this: CHEN Yenhang et al: Zheng He bao chuan fuyuan yanjiu" (Study about the Reconstruction of the Ships of Zheng He's Armada), in "Chuan shi yanjiu" ("Studies on the History of Naval Construction"), (2) 1986 --Concerning the value of 'chi' in the Province of Fujian; CHEN Yenhang, Zheng he bao chuan wei fuchuan xin kao (A New Study on the Ships of Zheng He's Armada), in "Zheng He yu Fujian", (92).

63 The Institute of the History of Natural Sciences, compiled by, Ancient China's Technology and Science, Beijing, Chinese Academy of Sciences - Foreign Language Press, 1986, p.480 -- The number put forward by investigators in the Chinese Academy of Sciences is ever greater: "[...] one hundred and fifty metres [...]."

64 MA Huan, MILLS, J. V. G., trans. and comm., Ying yai sheng lan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press - Hakluyt Society, 1970-- A work begun in 1416 and completed in 1435; A Description of the Chinese Junk 'Keying'[...], op. cit., p.31.

65 Excavations by the archaeologist, Otello Testaguzza.

66 SLEESWYK, André Wegener - MEIJER, Fik, Launching Philopator's 'Forty ', in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 23 (2) 1994, p. 115

67 MULLER JR., David G., China as a Maritime Power, Boulder, Westview Press, 1983, p.59

68 Ibidem., p.67

69 Ibidem., p. 109

70 BOXER, Charles Ralph, op. cit., p.112; apud THEVENOT, Relation de divers voyages curieux, vol.3, p.151.

71 BOXER, Charles Ralph, op. cit., p. 112; translation apud CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tractado em que se cõtam por est-eso as cousas da China cõ suas particulari. / dades, e assi do reyno dormuz cõposto por el R. padre frey Gaspar da Cruz da ord-e de sam Domingos. Dirigo ao muito poderoso Rey dom. Sebastiam noßßo sseñor., Evora, Impresso com licença, 1569..

72 GREEN, Jeremy - INTAKOSAI, V., The Pattaya Wreck Site Excavation, Thailand. An Interim Report, in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 12 (1) 1983, p.12.

73 GREEN, Jeremy, The Shinan Excavation, Korea: An Interim Report on the Hull Structure, in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 12 (4) 1983, pp.296-301.

74 GREEN, Jeremy, The Pattaya Wreck Site Excavation, Thailand. [...], 1983, op. cit., p.12.

* BA in History by the École d' Hautes Études, Sorbonne University, Paris. MA in Sociology by the Univerity of Tours, Tours, France. Bursar of the Cultural Institute of Macau.

start p. 201

end p.