§ 1. WORSHIP OF SEA GODS AND GODDESSES IN MACAO

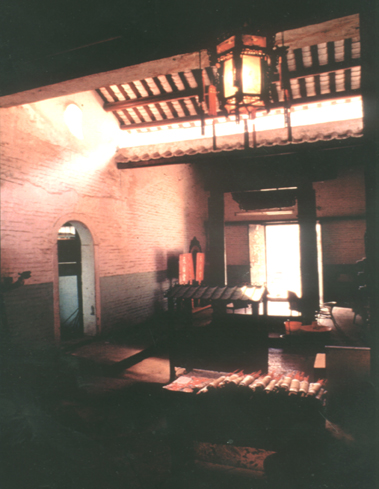

Chinese street temple, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

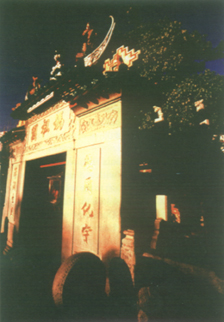

Chinese street temple, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

Two thirds of the earth's surface is covered by seas and oceans which humanity has been intensely related to since the beginning of time. For peoples, both Occidental and Oriental, who are closely related to the sea in their productive activities and daily life, worship of their protective sea gods and goddesses is an important part of their religious rituals. This kind of worship has continued into the present day, taking on new ideas and implications with social advances.

Situated on the southern tip of China overlooking the Nanhai· (South China Sea), Macao was an excellent seaport for East-West trade in the days of sailing-ships. So here, both Chinese and European seafarers have worshiped their respective maritime gods, goddesses and saints.

A self-contained system of worshipping seafarers' goddesses has developed from the traditional Chinese culture. Goddess Ama, having originated in Meizhou Bandao· (Meizhou Archipelago), Putian, · Fujian, · during the Song· dynasty, was already the Chief Goddess protecting maritime navigation in the early Ming· dynasty, thanks to dissemination by Fujian seamen and the repeated commendations of imperial rulers. Indeed, Goddess Ama (Mazu)· was devoutly worshipped by all seafarers and residents living along the Chinese coast. Macao is in Lingnan, · one of the regions where Goddess Ama is worshipped most fervently.

In 1401 (Yongle· reign, year 7) of the late Ming dynasty, when the great navigator, Zheng He, · returned triumphantly from his first voyage to the Xiyang· (Far Sea), recommendations were made to award Goddess Ama the title of Huguo Bimin Miaoling Zhaoying· (Heavenly Goddess Who Guards the Country and Protects the People with Miraculous Relief and Benevolence) and a shrine named Hongren Puji Tianfei Zhi Gong· (Heavenly Goddess Giving Relief and Spreading Benevolence) was erected in Nanjing. · A few years later a Fujian or Guangdong· merchant who was living in Haojing'ao· (Macao), one of the trading ports on the Guangdong coast, built Hongren Ge· (Pavillion of Benevolence), the first of ancestral Mazu Temple in Macao, at the southern point of the peninsula, near the entrance to the Inner Harbour. When the Portuguese occupied Macao during 1553-1557 (Jiajing· reign, years 32-36) this Mazu Temple had long been the signpost for Macao.

Following the general development of the territory there were more and more devotees of Goddess Ama. During Wanli's· reign a stone temple named Diyi Shenshan· (The First Holy Hill) was added to Niangma Jiao· (Goddess Ama's Quarters) which houses Hongren Ge. The reigning years of Kangxi· emperor of the Qing· dynasty witnessed the construction of the principal temple Zhengjiao Chanlin· (Forest of the Zen's Just Rectitude), Guanyin Ting· (Goddess of Mercy Kiosk) (Guangdongnese: Kun Iam) and Guanyin Ge· (Goddess of Mercy Pavilion) thus establishing the scope of the ancestral Mazu Temple as we know it today. Moreover, as Ama Miao· (i. e., Mazu Temple) has traditionally been administered by Buddhist monks and it has accumulated an enormous collection of couplets, tablets and scrolls over the centuries, it has become a prestigious, well-ordered ancestral Ama shrine and a famous historic site with a strong Chinese cultural background.

Also during Wanli's reign Chinese residents built Niangma Xin Miao· (New Temple of the Lotus) (Guandongnese: Lin Fung Miu), at the foot of Lianfeng Shan· (Lianfeng Mountain), which is a vital interlink of transport by land and by sea between Macao and Qingshan and the mainland. Since the Qing dynasty other ancestral pavillions and temples have been built on the Macao peninsular and the two outlying islands, Dangzi· (Taipa) and Luhuan· (Coloane), thus bringing the number of Goddess Ama's dwellings to a total of ten. Being the indisputable symbol of Macao, Ama miao (Guangdongnese: Ama Miu) is not only the ancestral temple of all these Ama shrines in Macao, but also one of the most renowned ancestral Ama Miao in China.

In addition to Goddess Ama, Chinese residents in Macao also worship Guandi· (Almighty God, God of Riches, Learning & War) (Guangdongnese: Kwan Tai), who together with Goddess Ama is considered the pillar of Chinese folk religious belief. Guanyin· (Goddess of Mercy) is the most influential of the Buddhist gods; and Lüzu· and Beidi· are the most prominent Daoist gods. To varying degrees, they worship all of them as gods and goddesses protecting them on their voyages. In the same way, Chinese residents are devoted to Sanpo· a derivative of Ama, Hongshengwang· (God of the South Seas) rich with characteristics of Lingnan popular religion; Yuecheng Longmu· (Dragon Mother), Tan Gong· (a Daoist god of seafarers) (Guandongnese: Tam Kung) and Zhu Daxian· (a sea god unique to Macao seafarers) (Guangdongnese: Tchü Tai Sin).

According to the religious concept of Chinese folk legends all prestigious gods are quanzhi quanneng· (Almighty) gods that 'know all and are capable of all' and those gods specializing in certain functions and being worshipped in various localities are 'gods of these places capable of performing these functions there'. Historically Macao Chinese residents had the same religious concepts. For example, Goddess Ama, while playing her major role as seafarers' protector, also blessed the people on land and brought happiness and prosperity to this region. On the other hand, Guandi the acclaimed and Guanyin, also take on the role of protecting seafarers and are worshipped along the coast. However, following economic development, improvement of transport and social progress, their role as seafarers' protector has gradually declined, while their other roles have become increasingly important.

In the West there were already a number of seafarers' gods and goddesses in ancient Greece and Rome. Greek and Roman mythologies were graced by the presence of scores of goddesses, all of whom protected seafarers. This tradition of worshipping first sea-goddesses and afterwards maritime saints in the West continued into the era of the Discoveries.

The Portuguese, being an outstanding seafaring nation, played an important part in these major geographical discoveries. In 1498 (Hongzhi· reign, year 11), Vasco da Gama's fleet sailed round the Cape of Good Hope reached the Malabar Coast of India, and discovered the new direct sea route from Western Europe to the East, thus pioneering direct contact between the two great civilizations of the world.

In the classic epic Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) by the eminent Portuguese poet Luís Vaz de Camões, the Goddess that gave blessing to Vasco da Gama's successful passage across the Indian Ocean is Venus, one of the goddesses in Roman mythologies. Venus was originally the Goddess of Orchards, but later worship expanded to include the Goddess Aphrodite. A combination of the two goddesses became the Goddess of Love, Beauty and Safeguarding Seafarers. Under Camões' pen, Venus to Vasco da Gama is like Ama to Zheng He. However in Catholic Portugal, the Venus of the Roman mythologies is regarded as a heathen. Indeed, had it not been for the tradition in Portugal and various Western countries of worshipping seafarers' gods and goddesses, this great epic with an inclination towards 'alien paganism' would never have been published amidst the strict censorship of the medieval Catholic Church: nor would it have drawn such warm and lasting responses from the whole Portuguese nation and peoples of Western countries.

Evidence for this tradition is also found in a Portuguese voyage in 1502 (Hongzhi reign, year 15). In that year the Portuguese arrived at an island in the South Atlantic Ocean, parallel to the western coast of Africa. They named this island Santa Helena (Saint Helena), which originated from Helen, a goddess in Greek mythology. Helen, daughter of Zeus and Leda, and her half-brothers the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux) were worshipped together as seafarers' goddess and gods [ sic ]. Though the island was subsequently occupied by the Portuguese, by the Dutch from 1513, and then after 1659 by the British, its name Saint Helena has continued to be used till today.

After settling in Macao from 1553 to 1557. the Portuguese continued to worship their western deities as devoutly as the Chinese residents worshipped theirs. In addition to Jesus Christ who was generally revered in all the churches of Macao as well as having the power to guard seafarers, chapels and cathedrals built on tops and slopes of hills seemed to have been specially dedicated to the Holy Mother, the Saint of Seafarers.

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

The Church of São Paulo (St. Paul's) was built in 1572 (Longqing· reign, year 6) and rebuilt during 1602-1640 (Wanli reign, year 30 to Chongzhen· reign, year 12). Its foundation stone was inscribed in Latin: Virgini Magnœ Matri, Civitas Macaensis Lubens, Posuit An. 1662 [ sic ]. Today this foundation stone still remains, embeded in the wall west of St. Paul's facade, which is covered with carvings and statues. On the facade, to the right of the statues of the Virgin and saints, are patterns of stone carvings with the Virgin Mary standing on the top right-hand corner and a Portuguese ship sailing below. The religious implication here is interpreted as 'Our Holy Mother the Ocean Saint leads the giant ship Representing the Church through the abyss of sins and evils' or 'Under Our Holy Mother's guidance a ship is crossing over the Ocean of Sins'.1 The latter interpretation is closer and more relevant to earthly life than the former. According to orthodox Catholic concepts the world is full of sins and the 'Ocean of Sins' is but nom de guerre for 'Ocean' tout court. St. Paul's, which used to overlook the sea, has on its facade the carved patterns of the Christian Holy Mother, the Ocean Saint, which could be understood as the signpost of the Holy Mother giving blessings to Western seafarers on their voyages in the East. Indeed, the success or failure of their seafaring would bear vitally on the survival and development of the Portugese residents of Macao at that time, success also ensuring that sufficient funds would be raised for the construction of churches and the maintenance of priests and missionaries.

Colina da Guia (Guia Hill) commands a panoramic view of Macao with the maritime area of Shizimen· (lit.: Cross Door) to the south. On its summit is the most ancient church in Macao, Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Guia (Our Lady of Guia), which houses the shrine of Our Lady of Guia. Built before 1622 (Tianqi· reign, year 2) the chapel offered a shrine for the Portuguese residents in Macao to worship their sea goddess, equivalent to Goddess Ama worshipped by Chinese fishermen from Fujian and Guangdong. 2

As to the origin of this chapel, myth has it that from 1573 to 1620 (during Wanli's reigning years) one day a Portuguese ship was sailing towards Macao. Somehow she lost her way in Jijing waters beyond the Outer Harbour of Macao but suddenly a flash of light appeared from the top of Guia Hill, lighting the way for the ship: it was the Goddess making her presence. So when the Portuguese set foot on Guia Hill, they erected this chapel to commemorate her appearance. As the date of her appearance was 5th August [of the Gregorian calendar] every year on this day the chapel is open to the public, and this practice has been going on till today. 3

The highest peak of the Macao peninsula is the Colina da Penha (Penha Hill), also with the Shizimen to its south, serving as an entrance to the Inner Harbour of Macao. On Penha Hill stands the Ermida de Nossa Senhora da Penha de França (Hermitage of Our Lady of Penha of França), probably so named because the goddess being worshipped came from the Portuguese Penha de França (lit.: Outcrop of France). The chapel was founded by the Augustins in 1622 and was renovated by their followers in 1624 (Tianqi reign, year 4). Anders Ljungstedt, a Swedish scholar, says in his introduction to this chapel: "Portuguese ships going into the harbour are accustumed to salute the hermitage with a few guns. Its revenue depends upon the liberality of individuals, and on promises seafaring people occasionally make in an hour of distress, to acknowledge by gratuities the favor, which they think the Virgin Mary bestowed upon them, in preserving their lives and prtoperty."4 Later, the Portuguese historian, Montalto de Jesus, gives a more detailed description:

"Where now stands the picturesque fort of Guia, stood the hermitage of Nossa Senhora da Guia; and on a flanking sylvan height the Augustine monks had their hermitage, dedicated to Nossa Senhora da Penha de França 1. Notre Dame de France the protectress of navigators, in whose honour Portuguese ships fired a salute when approaching Macao, while in response the hermitage bell rang a merry welcome; and to the chapel of Penha the crew, on landing, went with their families barefooted for a thanksgiving, dropping there pecuniary offerings which sometimes took the shape of liberal endowments promised in the hour of grat peril and distress on the high seas - an usage which found a parallel in that of Chinese sailors, who, when passing by the Ma-Ko Pagoda [Ama Miao], offered sacrifices to the goddess Tien How [Tianhou] to propitiate voyage."5

The Church of São Lourenço (St. Lawrence), situated in the southwest part of Macao peninsula, is one of the three oldest existing churches in Macao. It used to stand on the coast of Praia Grande, facing the Shizimen. Founded in 1659 (Longqing reign, year 3), the first renovations took place in 1618 (Wanli reign, year 46). The chapel had a post for hoisting typhoon signals in its early days. On the altar stands the handsome figure of the patron saint depicted as a young man in magnificent vestments; one hand holding a book and the other a holy musical instrument, with a full solemn face, bright eyes looking into the distance [...]. This is the young St. Lawrence, a Catholic maritime saint, who, "[...] in the hearts of seafaring Portuguese, gives you peace and ensures safe and plain sailing."6 [...]

§2. CHINESE SEAFARERS' DEITIES IN THE EYES OF WESTERNERS

The Chinese residents of Macao had created Hongren Ge of the ancestral Ama Ge and had bred for many generations in this Chinese territory, by the time the Portuguese maritime navigators and the Jesuits arrived to see it. This was the first time that westerners began to notice seafarers' deities worshipped by the Chinese people.

Having long been the signpost of Macao, Portuguese seafarers and the Jesuits accepted it as a symbol of Macao. The very name of Macao originating from Ama Ge (Ama Pavilion) provides strong evidence for this.

Fernão Mendes Pinto, a Portuguese navigator active in East India in mid sixteenth century, wrote a letter from Macao dated the 20th November 1555 (Jiajing reign, year 34) to the Superior of the Society of Jesus in Goa, spelling the name of Macao "Ama cuas". Three days later, Jesuit Belchior Barreto writing to his colleagues in India, began: "Dated 23 November, 1555, posted from Machoan Port, China".7 These are accepted as the earliest records concerning the name of Macao.

According to the Portuguese scholar José Maria Braga, during this period 'Macao' was also spelt in Portuguese "Amaqua", "Amachao", "Amacao", "Amaquao", "Amaquam" and "Maquao".8After the seventeenth Century, there were a variety of Portuguese transliterations, like "Amaugau", "Machuon", "Machuan", "Amakau", "Amakao", "Amangao" and "Amacon". The Portuguese "Porto de Amacao" became the "Port of A-ma", or "Harbour of A-ma" in English. 9

These transliterations show the origin of the Portuguese name of Macao. Since the beginning of the century, both Eastern and Western scholars have done a lot of useful research in this particular area. There has been a general consensus that "Machoan", "Macahuon" and "Machuan" originated from 'Mazu'. And most scholars will agree that "Amaquam, "Amacon, "Porto de Amacao" and "Port of A-ma" can be traced to (Ama Gang). However, "Amaqua", "Amachao", "Amacao", "Amacuao", "Amaquao", "Amaugau", "Amakau", "Amakao" and "Amangao" are variously retranslated into 'Ama Ao',· 'Ama Jiao',· 'Ama Ge',· 'Ama Gang',· etc. 10 But the author would argue that they should be put back to 'Ama Gang' or 'Yama Gang'.

To begin with, 'Ama Gang' or 'Yama Gang' is semantically and lexically identical to Mazu Gang, only with a slight difference in the wording of salutations. The salutation of Ama Gang is closer to that of Chaozhou dialect of Minnan· (southern Fujian), and here we find clear evidence in the poems of Wu Qibao, · of Xiangshan, · during Jiaqing's· reign of the Qing dynasty. One of his poems is entitled You Ama Ge Guanyin Ting· (Travel in Ama Pavilion and the Goddess of Mercy Kiosk). 11 Meanwhile, the salutation of Yama Gang is more similar to that of Guandongnese dialect. In the Guangdong yanhai tu· (Atlas of Guangdong), by Guo Fei· during Wanli's reign of the Ming dynasty during Wanli's reign, there is a map of 'Haojing Ao'· on which we find the three characters Yama Gang· near the berth of Portuguese ships in the Inner Harbour. 12 Yama Gang is a variant of 'Yama Gang'. Therefore, we can see that 'Ama Gang', Yama Gang and Haojing Ao were the early names that the Chinese gave to Macao or the port of Macao, and the many variants found in Portuguese documents were transliterated from Ama Gang of Chaozhou dialect or Yama Gang of Guangdong dialect. Indeed, 'Amaquao' and 'Amaquam' are both transliterations of 'Ama Gang' or of 'Yama Gang'. Only later, they lost their nasals through use.

By analogy, 'Macau' in modern Portuguese and the English 'Macao', as well as 'Maquao', must have evolved from 'Amakau', 'Amacao' and 'Amaquao' respectively, all leaving out the salutatory "A", i. e., the Chinese 'A' 阿 or 'Ya' 亜. Thus 'Macau' and 'Macao' should be retranslated into ' Ma Gang' or Ma Gang, and not 'Ma Ge' or 'Ma Jiao'.

Furthermore, some Portuguese compound words or combinations of words also originated with this Mazu Miao (Ama Miao). In 1583 (Wanli reign, year 11), the Portuguese also called Macao 'Porto de nome de Deus' ('Port of the Name of God'), in addition to 'Porto de Amacao'. Later, they also called Macao 'Cidade do Nome de Deus na China' ('City of the Name of God in China'), in 1654 (Shunzhi· reign, year 11), king Dom João IV of Portugal, gave order to the then governor of Macao to have the words "Cidade do Nome de Deus, Não Há Outra Mais Leal" ("City of the Name of God, None more Loyal") inscribed in Leal Senado's (Municipal Council) building to commend the Portuguese community in Macao for their loyalty to their fatherland during the Spanish annexation (1580-1640) of Portugal. Here we witness the subtle change in the Portuguese name of Macao: from 'Ama' ('Mazu') to 'Deus' ('God').

To some extent this subtle change reflected the change of attitude within the Portuguese community towards Ama Miao as the symbol of Macao: accepting with reservation then finally ignoring it altogether. There were both religious and political reasons underlying this change of attitude.

Religiously, the Portuguese have always been devout Catholics. In the concepts of medieval Catholic orthodoxies, Ama is an alien deity worshipped by heathens and should have been rejected. Miraculously however, Ama held certain appeal for these early Portuguese arrivals, who joined Chinese seafarers in their worship of Goddess Ama. Fr. Benjamin Videira Pires, contemporary historian of Macao Catholicism, claims: "It is not accidental that the Portuguese and the Chinese peoples met on. this peninsula of Ama Miao, living together [...]. While the Ama Festival is being celebrated in the Ama Miao in early May (of the the Gregorian calendar), the Portuguese people are celebrating their Virgem Maria (Virgin Mary) and Nossa Senhora de Fátima (Our Lady of Fatima) festivals. [...] Is this a coincidence? [...](The Fujianese) brought spiritual notions imbued with passions for their old homeland and embellished with local colours to Macao. And so did the first batches of Portuguese people who settled here. Inadvertently they brought to Macao their custom of visiting seaside hills to worship their Virgin Mary. This custom stemmed from a life of seafaring, especially a spiritual, pastoral life."14 It was this primary religious notion held by early Portuguese seafarers that transferred their worship of Virgin Mary to the worship of Goddess Ama, resulting in an identity that made it possible for them to accept Ama miao as the symbol of the territory of Macao.

Nevertheless, this identity could not change the orthodox Catholic concept that Ama was an alien idol worshipped by heathens. The change of meaning into the Portuguese 'Deus' brought about the transformation of the Chinese 'Ama' into 'Heaven' or 'God' inherent in the western mind. And the switch from 'Cidade do nome de Deus na China' to 'Cidade do nome de Deus' ('City of the Name of God'), reveals that in the mind of the imperial court of Lisbon, Macao no longer belonged to China but was a Portuguese territory; the Portuguese subjects were "ever so loyal" not to the Emperor of Imperial China, but to the King of Portugal.

The Jesuits who accompanied the Portuguese seafarers to Macao also noticed the Ama miao of Hongren Ge. Matteo Ricci also visited Hongren Ge during his stay in Macao, from the 7th of August 1582 (Wanli reign, year 10) to 10th September 1583 (Wanli reign, year 11). He still had fresh and vivid memories of this Ama miao in 1609 (Wanli reign, year 37), when he wrote:

占城十日遏交欄,

十二帆飛著溜還。

握粟定留三佛國,

采香長傍九洲山。

("On this little peninsula there were statues built for Goddess Ama. They can still be found. This place is called Macao. Instead of 'peninsula', I would call it a giant protruding rock."). 15

In the same year, when discussing the problem of the Portuguese settling in Macao, he wrote again:

自占城靈山起程,

顺風十晝夜可至。

("There they worship a goddess called Ama. That is how the port got its name. In Italian, it means 'the port of Ama'."). 16

Indeed, Matteo Ricci's knowledge of the religious culture of China began with "[...] this goddess called Ama." And because of his deep understanding of Chinese religious culture, he adopted a tolerant attitude towards the Chinese rites of paying respects to Heaven, to Confucius and to Ancestors, thus reducing the resistance from the Chinese traditional culture to the spreading of Catholicism and enabling the missionaries to carry on their work successfully. Later the Roman Curia rejected Matteo Ricci's conciliatory approach to missionary work and forbade Chinese Catholics to observe their Chinese rituals, which prompted the Kangxi emperor to order a ban on Catholicism. This was a serious blow to missionary work in China.

This situation continued for almost a century, during which the Catholic Church in Macao kept on interfering with Macao Chinese residents celebrating the birth of Ama.

Now I would like to discuss the historical context the chapter under the heading Objections to Chinese Recreations at Macao [A section within Part IV - Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China ] from the book An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China; and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China & Description of the City of Canton by the Swedish author Andrew Ljungstedt.

As mentioned above, the Roman Curia rejected Matteo Ricci's approach to missionary work that allowed the Chinese to observe their own rituals. They dismissed these practices as superstition and idol-worshipping. Under this influence, the Catholic Church authorities in Macao felt disgust at the sight of parades and rejoicing among the Chinese residents during the Ama festival and adopted a hostile attitude towards them. In 1735 (Yongzheng reign, year 13), Francisco da Rosa, the acting Bishop of the Catholic Church in Macao, went so far as to give orders to demolish the stage on which some Chinese residents were performing. As the worship of Ama was a long established component of Court rituals, with enthusiastic official and popular participation, this blatant interference led to the unavoidable deterioration of relations with the Qing dynasty Government and the Chinese residents in Macao. In turn this was bound to put the Portuguese and the Church's interests in Macao in jeopardy. Most probably, this is why the Governor of the Portuguese State of India wrote in 1736 (Qianlong reign, year 1) to the Municipal Council of Macao, ordering the Senate of the Macao Bishophry to denounce the acting Bishop and warn him not to interfere with these and similar activities again.

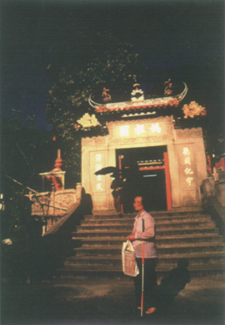

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

Unfortunately this sensible advice and warning was ignored. Instead, the Disciplinary Board of Roman Curia wrote in 1758 (Qianlong reign, year 23) to the Bishophry of Macao and the Portuguese authorities, ordering them not to tolerate any performances or parades put on by heathens. Fortunately some major officials of the Portuguese administration of Macao, believing that the Portuguese had no right to exercise jurisdiction over the Chinese community, reacted cautiously and tacitly allowed the Chinese residents a brief period of entertainments and recreations. But in 1780 (Qianlong reign, year 45), at the instigation of a representative from the Disciplinary Board of the Curia, who was in Macao at that time, the Senate gave orders to the Church minister to have the stage burned down. However, he failed in this attempt because the local representative of the Chinese Government had already endorsed the plan to elevate the temporary stage. The Chinese advised the Portuguese not to arouse public indignation by repeatedly committing extreme acts.

In 1816 (Jiaqing reign, year 21), Fr. Dom Francisco de Nossa Senhora da Luz Chacim the Vicar-general of the Bishosphry of Macao, seeing that it was impossible to stop the festive activities already arranged by non-Christians, decided to resort to exerting spiritual influence on Catholics belonging to his subsidiary centres in Macao. So on the 15th of April 1816 (18th of the 3rd Moon of the lunar calendar) i. e., five days before the holy birthday celebrations, 17 Fr. Chacim issued a warning announced by his assistants at their respective centres. In a fatherly, persuasive tone, the statement warned that, in order to save their souls, no Christians should be in the streets or peep through the shutters at the Chinese paraders when the procession passed by. Those who violated this rule would be expelled from the Church. However, it was almost impossible to implement this punitive measure. Of all the Christians in Macao, no more than fifty were adults, who could resist the temptations. The others found it a great pleasure to watch the rejoicings. The Chinese rituals were really something and the celebrations lasted three whole days. Evenings found the marketplace lit up with bright lights, with all sorts of interesting Chinese performances going on. 18

This is a description of what Andrew Ljungstedt, Consul and taipan of the Swedish East India Company witnessed a rousing scene of the Chinese residents celebrating the holy birth of Goddess Ama. Not only did it intoxicate this European Protestant, but also many a European Catholic, who could not even "[...] save his own soul [...]."

In early Qing dynasty, the Portuguese authorities in Macao were already aware that they had no right to interfere with life and customs within the Chinese communities. Later, they continued to adopte a non-interference attitude to Chinese rites and rituals. In the early years of the Nationalist Republic, Wang Zhaoyong· wrote: "The Chinese mostly [...] stick to their old customs, and the Portuguese officials do not forbid them."19 In 1927 (Republic, year 16), when the Ama Miao (Guangdongnese: Tianhou Miao)· in Coloane was under repair, the then Governor of Macao, Rodrigo José Rodrigues donated three yuan. 20 Indeed, this sensible 'non-interference' policy to and compliance with Chinese rituals was an important condition for the survival and growth of the seafarers' patron gods and goddesses in the Chinese traditional culture of the recent past.

In recent years, as belief in the patron sea goddess has become more influential internationally, the Roman Catholic Church has adopted a more relaxed and receptive attitude towards the religious belief in Mazu. In 1954, when representatives of Catholics from all parts of the world met in the Philippines, the Pope nominated Mazu one of the seven Catholic saints and solemnly crowned her, culminating in the appearance of Goddess Ama in Western vestments. 21Goddess Ama, to some extent, represents traditional Chinese culture. The transformation of Ama from a heathen goddess to one of the Catholic Saints was the result of long standing East-West cultural exchanges and the globalization of worship of Mazu, with cultural implications distinct from the assimilation of Mazu into Buddhism and Daoism. This distinction will bear importantly on the study of Mazu by contemporary Western scholars, including Portuguese researchers in Macao. It can be expected that Westerners' understanding of Mazu will continue to deepen as East-West cultural exchanges expand.

Treading on the heels of Portuguese navigators and Catholic missionaries were European artists of the nineteenth century, who eyed the Ama miao from an artistic rather than a religious perspective.

George Chinnery, the renowned British painter, arrived in Macao from India in 1825 (Daoguang· reign, year 5). He took up residence in Rua de Inácio Baptista (Inácio Baptista Street), close to the Church of St. Lawrence. He lived in Macao until his death in 1852 (Xianfeng· reign, year 2), leaving us a great number of paintings of the sights of Macao. He seemed to have a special liking for Chinese views and scenes, from Chinese sailing boats, tanca boat dwellers, and tanca women to hawkers, craftsmen and other people of the lower strata. He was fascinated by the Ama miao.

I had the good fortune of seeing six of Chinnery's paintings of Ama Ge, which were included in a collection published by Leal Senado in 1985, two of them being close views on land. One is a pencil drawing of 1833 (Daoguang reign, year 13) depicting the foreground of the principal palace of Ama Ge, with glazed tiles shining in the air and the moon-gates revealing the most enchanting spectacles -- in short, a masterpiece expressive of the vigour and splendour of the religious architecture of China. The other, created in 1834 (Daoguang reign, year 14) shows Ama Ge from various angles: the palace gate guarded by stone lions and stone drums planted on both sides, flights of stone steps, lanterns hanging on the doors, all typical of Chinese temples.

Chinnery must have most enjoyed delineating Ama Ge in different perspectives from a boat along the North Bay, extending his views to include a variety of figures from tanca fishing boats to fisherfolk. All the other four pictures show this and are pen drawings: there is the front view, the east view and the other two west views of the temple. In these drawings we see little sampans appoaching the shore, boatmen taking a break, ripples spreading with the sea breeze, the holy banners fluttering, passengers getting on and off the ferry and fishing junks netting a haul of fish, all happening around the temple as if to convey the theme of the perfect relationship of interdependence and harmonious coexistence between man and god.

William Prinsep, a student of Chinnery's, depicted Ama Ge in the same vein. A coloured lithograph of fine brushwork created by him in about 1838 (Daoguang reign, year 18) shows that he faithfully followed Chinnery's example in plot and theme. 22

Another Western painter who had a special liking for the views and sights of Macao was a young French painter by the name of Auguste Borget, who stayed in Macao and Guangzhou from August 1838 to June 1839. His most celebrated published work Sketches of China and the Chinese comprises a selection of paintings and letters from this stay in China.

Borget was extremely fond of the scenes and views of Ama Ge, perhaps even more so than Chinnery. This European Christian artist, took to this Mazu Temple as soon as he stepped onto the shore of Macao. He wrote from Macao:

"Macau, 2nd of May, 1839

My dear friend, it is so difficult to explain things Chinese in a European language that I have still not dared to speak about the Great Temple of Macau, the most exquisite marvel I have seen in this land. [...] I come here almost every day. The Chinese name is Neang-Ma-Ko which means 'Old Temple of the Lady'. It is crowded from dawn till dusk when the trees, stones and rooftops glitter under the sun's rays. It is even busy in the middle of the day when I am obliged to take refuge under a shade to protect my work. [...] I have never gone there without discovering some interesting scene, some exciting new detail which had escaped my view on a previous visit. On every visit I feel the joy of the explorer. Whatever place I have chosen, I always have a new drawing, a picturesque scene. In fact it would be possible to make a fascinating album just recording the temple and its grounds. From the point of view of Chinese art, everything concerning the layout of this building is admirable: the harmony of its structure, its location in the midst of ancient rocks and trees and the multitude of ornaments with which it is covered. This is really the most interesting subject a European could choose. I have been assured that in none of the great cities of China is there a more outstanding temple, and I can believe it, so much better it is than those I have seen elsewhere."23

Obviously, this European with his unique intellectual insight, appreciated the whole of Ama Ge as a perfect artistic creation, thus uttering exclamations of unreserved admiration. I have seen four of Borget's works themed on Ama Ge, all being colour litho brushworks. Two of them are pictures of Hongren Ge. One shows an old lady praying in front of the temple, two men burning incense beside the temple, and a man of high position, surrounded by his servants, looking at some distant views beyond the Inner Harbour. The other shows a woman with bound feet walking towards the altar to pray, being followed by a tanca woman with a little child on her back also intending to pray, a man and a youngster burning incense, and a tanca workman with a bamboo hat on his head taking a rest while smoking from a pipe. All these would be everyday routines at Hongren Ge. As the two pictures are almost identical in the layout of the temple and their description of natural views, they must have been the products of repeated sketching of the same locality.

The other two pictures similarly describe the front of the principal palace, the gate of the temple, as well as crowds of people hustling about in the foreground. In front of the temple, there are foodstalls and stalls for fortune-telling and gambling. The people portrayed include blacksmiths, carpenters and beggars. On the yellow banner hoisted on two masts over the temple are written four Chinese characters: "Huguo Bimin"· ("Safeguard the Country and Protect the People"), which are still visible, though obscurely. 24

Edward Hildebrandt, also a European painter, came to Macao in 1838, the same year as Borget. He drew a magnificent scene In fine brushwork and elegant strokes of the exciting activities and performances held by Chinese residents at Ama Ge during the holy birthday celebrations. This painting, created sometime in the 1860's (Xianfeng reign, year 10 to Tongzhi reign, year 9) belongs to the Hong Kong Museum of Art collection of paintings by nineteenth century Western artists on the themes of Hong Kong, Macao, Guangzhou and Guangdong. In the picture we see a huge bamboo canopy temporarily built up in the foreground of Ama Ge, with many low booths, probably used as temporary vending-stalls, stretching from the Moongate of the principal temple all the way to the seashore, with a row of tiny tanca huts behind the canopy, probably serving as temporary toilets. The show has already started; the huge canopy is full of people with more late-comers streaming into it. A few fans who have failed to find seats had gone so far as to climb onto the roofs of the little huts and are watching the show from there. Scores of tanca boats and fishing junks are moored along the shore, showing that these boat dwellers, who brave the sea all the year round, could also enjoy a few days of leisure, visiting Ama for her blessings and some fun. Beyond two big ships are berthed indicating that the merchants and crew are also immersed in the festive celebrations ashore. In the lefthand corner of the painting are written the words: "Macao Sing Song".25 What a spectacular Macanese singsong!

Hildebrandt did a watercolour depicting the everyday activities at Ama Ge, viewed at a distance from a boat berthed at the mouth of the North Bay, and positioning the principal temple of Ama Ge in the middle, between the blue sky and the sea. 26

With the development of the camera from the west began to focus their lenses on Ama Ge. In 1844 (Daoguang reign, year 24), that is seventeen years after world's the first photograph appeared in France in 1827, the French Théodore de Lagrene Mission, which was to negotiate and sign an unequal treaty with China, arrived in Macao. Among the French delegates was Jules Itier, representative of the Finance & Trade Ministry of France: he had in his luggage a wooden chest filled with heavy cameras and other devices for photography. 27

After the signing of the Sino-French Huangpu Treaty on the 24th of October 1844, Jules Itier could find time to photograph the most famous views of Macao, including the South Bay (Baía da Praia Grande), the North Bay (Porto Interior), the Shizimen (Cross Gate) and Ama Ge (Ama Pavilion). There are two photographs of Ama Ge, one of the facade of the principal temple, and the other of the gate with a horizontal scroll hanging between two lanterns, on which we can detect and discern the four big Chinese characters "Tian Shang Sheng Mu" ("Holy Mother of Heaven"). Owing to the crude film exposure of that time, except for the buildings in the middle, the whole background of the picture is a mass of darkness, which may have set one wondering is this palace of 'Holy Mother of Heaven' situated in Heaven or on Earth? This is the "[...] very first photograph taken in China."28

§3. WESTERN SEAFARERS' DEITIES IN THE EYES OF THE CHINESE

The Chinese people's awareness of Portuguese seafarers' patron deities began with the great Ming dynasty dramatist and poet, Tang Xianzu. · Originally libu· (Minister of Rituals and Education) in Nanjing, Tang Xianzu was demoted to a petty official in Xuwen County, Guangdong, because he had been critical of the Imperial Court. On his way to Xuwen Tang Xianzu passed by Xiangshan Ao· (i. e., Macao). In four of his poems he described the sights and views of Macao tinged with an exotic foreign flavour. In his Ting Xiangshan Yizhe· (Listening to the Interpreter in Macao), he wrote:

"In ten days I reached Jiaolan· from Zhancheng,

Aboard a big ship with twelve sails flying.

Millet in hand, they settled in San Buddha Land,

While burning sweet incense by the Jiuzhou Shan."·

Jiaolan is a place very familiar to ancient Chinese seafarers active in the South China Sea. Fei Xin, who went on voyages to the South Seas with Zheng He, also wrote in Jiaolanshan· (The Jiaolan Mountain) of his collection entitled Xing Cha Sheng Lan· (Cruising Under the Stars):

"[...]

Setting out from Lingshan, Zhancheng,

We can reach Jiaolanshan in ten days,

If all is plain sailing with the wind.

[...]."

However, in Tang Xianzu's poem the "big ship" that followed Zheng He's sea-route was not a Chinese ship, but a Portuguese one; for a Chinese ship's mast only supports one sail while a Portuguese ship's masts supports several sails. The "twelve sails" in the poem made clear that it was a Portuguese ship with several masts and many more sails.

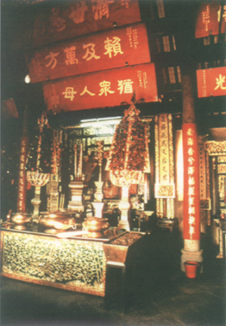

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

Portuguese ships navigated the seas and oceans with the help of "[...] three compasses on board each ship: one placed in a 'shrine', one in the stern, and the third amidst the masts, all matching with one another for safe sailing."30

The 'shrine' on board the Portuguese ship was there for the worship of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and other patron male and female saints protecting maritime navigators. And like the altar aboard Chinese ships for the worship of Goddess Ama, the shrine was the spriritual pillar and support for all officers and crew on board.

So just as Professor Zhu Jieqin,· expert in the history of marine transportations, says, "Go back a hundred years, not only Chinese seafarers were superstitious, but also Western navigators."31

The ritual of 'millet in hand', a reference from Shijing -- Xiaoya -- Xiaowan· (The Book of Poetry),"Wo Su Chu Pu"· meaning 'giving a handful of millet to the servant to pay for fortunetelling'. We could surmise before setting sail that this Portuguese ship may have resorted to praying or fortune-telling to decide on the voyage and the route of navigation. Accordingly she dropped anchor in the port of "Sanfoqi"· (lit.: San Buddha Land), and then sailed to "Jiuzhou Shan" ("Jiuzhou Mountain") of the Malay peninsula to purchase ambergris and other perfumes. 32 All this demonstrates that the Portuguese seafarers, like their Chinese counterparts, depended on their patron gods and goddesses for guidance and blessing in the infinite unpredictable world of navigation.

During the Ming dynasty, Portuguese ships cruising Chinese waters usually had Chinese interpreters serving as intermediaries or go-betweens. Macao being a prosperous East-West trading port also engaged Chinese interpreters. It was from them (i. e., Xiangshan Yizhe· (The Macao Interpreter)) that Tang Xianzu learned that Portuguese ships also depended on fortune-telling for decisions concerning their sea voyages.

In reference to Portuguese ships cruising and trading between Macao and the West coast of India, Yin Guangren· and Zhang Rulin, · of early Qing dynasty said: "These Portuguese ships must rely on compasses for direction. [...] Every ship has on board three compasses, one in the shrine, one in the stern and the third amidst the masts. All three compasses must match accurately against one another to make sure that the sailing will be safe and successful. The haiguan jiandu· (Customs Supervisor) issued twenty-five licenses to Portuguese ships, with the initial Chinese character xiang· preceding each serial number'.33 This quota had been set by Kong Yuxun,· liangguang zongdu· (Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi), · and these twenty-five Portuguese ships all had shrines on board.

As described in Chapter One, the Portuguese settlers had chapels and churches built on hilltops and high mountain slopes of Macao to worship their patron saints. On the top of Penha Hill stands the Hermitage of Our Lady of Penha de França which was rebuilt in 1935. On its roof stands the white marble statue of Our Lady wearing a Crown and holding in her arms the Holy Baby Jesus facing towards the Shizimen. It was Our Lady that had given protection to the Portuguese ships cruising the seas. Admiring this statue of Our Lady of Penha de França, we immediately think of Goddess Ama, the Holy Mother in Heaven and of the Chinese Guanyin-in-White.

In front of the chapel, on the platform, stands another statue: the Virgin Mary of Misericordia crossing her fingers while looking out over the Oriental seas. Since the early Christianity European artists have tended to place great emphasis on the Virgin Mary's maternal instinct and love in their statues of her. This statue of Our Lady gives the sensation of a passionate mother standing on top of a high mountain, fixing her earnest gaze into the distance over the sea and praying for the safe return of her seagoing son. As the statue faces the sea in the past it was called 'Guanyin looking out to the sea'34 by the Chinese residents of Macao, who took it for granted that the white marble figure overlooking the sea was their own Guanyin-in-White.

Author's note: Today's Semarang, Sumatra, Indonesia

The practice of comparing the Virgin Mary to Guanyin became popular in the late Qing dynasty. In 1900 (Guangxu reign, year 26) Liang Qichao· wrote two poems in praise of the Portuguese taking in procession the picture of the Virgin Mary:

1.

一年兩度出觀音,

大廟迎來旅若林。

扈從十分虔謹事,

沿途經咒誦沉吟。孏

("Twice a year Guanyin is out going her rounds.

The Big Temple is filled with pilgrms,

Faithful and meticulous with the rituals,

Chanting and praying to Buddha all the way.").

2.

風信名垂廟祀華,

年年禮拜動淸笳。

洋人數典難忘祖,

姓字猶談嗎唎呀。

("All is ready for the celebrations

That are held every year to worship Her.

The Portuguese are faithful to their ancestor,

Chanting the name of Mary or Maria."). 35

In a paper entitled Qingdai Aomen shi zhong guanyu tianzhujiao de miaoshu· (The Influence of Catholicism in the Poetry of Macao during the Qing dynasty), I wrote: "The Chinese people's understanding of Catholicism in the Qing dynasty was inseparable with the traditional Chinese culture that underlies it. In other words, the Chinese viewed Catholicism representing the occidental culture from the perspective of their own traditional Chinese culture."36

This was how the Qing dynasty Chinese perceived Western seafarers' patron deities. So when the Chinese scholar Liang Qichao· witnessed the scene of the Portuguese faithfully worshipping their Virgin Mary, he immediately associated it with that of the Chinese worshipping their Buddha and their ancestors.

The Church of St. Lawrence situated in the southwest part of the peninsula, has always been called Fengshun Miao, Fengshun Tang or Fengxin Miao (Temple of Plain Sailing) by the Chinese. Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin wrote in the early years of Qianlong's reign:

西南則有風信廟,

蕃舶顯出。

室人曰跂其歸,

祈風信于此。

("There's the Temple of Plain Sailing in the southwest.

Portuguese ships are out on a voyage, while families and friends are waiting

And praying for their safe return.

So here, in this chapel, they pray for good wind, fine weather and plain sailing."). 37

Probably the Chinese at that time presumed that this chapel was for the worship of the God of Weather, to give protection to Portuguese seafarers by blessing them with good wind and fine weather, so they called the chapel Fengxin Miao or Fengshun Tang.

The Portuguese did use to come to this chapel to pray for plain sailing. The Chinese compared it to the Chinese religious custom of seafarers and their families worshipping their patron deities like Goddess Ama and qifeng, · i. e., praying for good wind before they set sail. In 1691 (Kangxi reign, year30), Gong Xianglin, · Guangdong (Customs Superintendent) said in his Zhujiang fengshi ji· (Zhujiang Memoirs):

蕃舶之出于冬月,

冬月多北風,

其來以四五月,

多南風。

既出則澳中黑白蕃一空,

計期當返,

則婦孺繞屋號呼,

以祈南風,

亦輒有驗者。

("Portuguese ships usually set sail in winter, when the north wind blows, and they come back in April or May, when the south wind blows. When the ships are out on voyages Macao is empty, without foreigners black or white. And when it is about time for them to return, wives and children start chanting around the house, praying for the south wind. And so comes the south wind." ).

Pan Youdu· in a poem included in his Xiyang Zayong· (The Potpourri on the Portuguese) wrote in the same vein in 1813 (Jiaqing reign, year 18):

祈風日日鐘聲急,

千里梯航瞬息回。

("Praying for good wind, the bell's ringing louder.

All at once, sailing ships return, from afar.").

The poet had a note to this poem: "The Portuguese have the custom to daily ring the [church] bells and to pray for good wind and plain sailing."38

Close by, east of St. Lawrence's is the Sé (Cathedral) housing the shrine of the Virgin Mary. One of the earliest churches in Macao, it is known to the Chinese as Da Miao· (Big Temple), Wangren Miao· or Wangren Si· (Temple of Hope -- Waiting hopefully for their men to return with ships of wealth). It acquired this name, according to Li Pengzhu· because "[...] as the cathedral was erected on top of the hill, and there were no tall structures or skyscrapers around or in the way, you could have a full view of the harbour from the peak, watching the ships sailing or berthing. So, many Portuguese women used to walk up here, waiting for their men to return [...]. 39

During 1796-1820 (Jiaqing's reign), a Shunde· poet, Liao Chilin, · in his Aomen Zhuzhi Ci· (Macao Bamboo Poems), described Portuguese wives praying for good wind at this cathedral:

朗趁哥斯萬里間,

計程應近此时還。

望人廟外占風信,

腸斷遙天一發山。

("Her man's been sailing thousands of miles away from the coast

Counting days and nights, she knows it's time he's returning.

Distressed, she prays for good wind outside Wangren miao,

Heart-broken, she looks to Heaven to bless her man plain sailing."). 40

Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin, in their discussions about the interrelationship between Portuguese wives 'praying for good wind' and their livelihood, said: "[..] customarily, their husbands were maritime merchants. [...] A ship was worth a fortune. Wealthy families bought their own ships. [...] Those less well off became helpers or joined hands and became partners. A ship might be owned by dozens of partners. The ship set sail once a year, and once she was on a voyage, scores of families and their lives and fortunes were involved. [...] So when the ships were coming home, their wives and children started chanting and praying for good wind around their house. Women and children, often numbering a thousand, went on chanting and begging for south wind in the street until the ships came home."41 The Portuguese wife in Liao Chilin's poem came to Wangren miao in early summer when ships were returning from the west coast of India and the southwest wind prevails and saw the wind was not favourable for sailing. In sorrow, she fixed her gaze to the horizon, worried about her husband's life and the misfortune of her whole family.

In the early years of the Min'guo· (Nationalist Republic), Wang Zhaoyong, also wrote a poem on Portuguese wives praying for good wind and plain sailing:

蕃婦祈風信,

亦如祠浮屠。

鯨鐘響鞺鞳,

流聲播海隅。

神道以設教,

華舞甯或殊?

("Portuguese wives worship the God of Weather and Wind,

Just as the Chinese worship Buddha and Guanyin.

The ringing of the bell resounds here and there,

Sending ripples and echoes all over seas and oceans.

Both are religious rituals with powers divine.

East or West, can anyone see any difference?"). 42

He too was making these observations on the Portuguese custom of worshipping their sea deities from the perspective of the traditional Chinese culture.

§4. CONCLUSION

As the important link of Sino-European cultural exchanges during the Ming and Qing dynasties, Macao is the meeting point for the worshipping of Oriental and Occidental seafarers' deities and saints. The Chinese and European maritime navigators, while worshipping their respective patron deities in the context of their respective cultural traditions and religious conventions, examine each other's patron gods, goddesses and saints from the perspective of their own cultural traditions, thus giving rise to some very interesting cultural phenomena in those days.

Portuguese seafarers living in Macao drew an analogy between Goddess Ama, worshipped by their Chinese counterparts, and their ardently worshipped Virgin Mary. The Chinese residents of Macao, on the other hand, compared the Virgin Mary, worshipped by their Portuguese counterparts, to Guanyin and Goddess Ama. Here in Macao, 'Virgin Mary Gazing at the Sea', 'Guanyin Looking at the Sea' and 'Holy Mother of Heaven' seemed to have become synonymous. From this perspective that we may get a better view of Macao's role and status in the history of Sino-Eu-ropean cultural interflow.

Translated from the Chinese by: Ieong Sao Leng, Sylvia 楊秀玲 Yang Xiuling

Ama Miao 阿媽廟 Ama Miu, Macao.

Photograph taken in 1990 by Amilcar Carvalho.

NOTES

1 VALENTE, M. R., Igrejas de Macao: Churches of Macao, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1993, p.66; "St. Paul's", 1993, (colour photographs), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, [n. n.].

2 LI Pengzhu, 《澳門古今》 (Macao: Past and Present), Hong Kong - Macau, Hong Kong San Lian 三聯書店 - Macao Star-Light Publishing 星光書店, 1986, pp.23-124; VALENTE, M. R., op. cit., p.92.

3 BU Yi, 布衣《澳門掌故》, Hong Kong, Wide-Angle Publishing House 香港廣角出版社, 1979, p.32.

4 LJUNGSTEDT, Anders, An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China; and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China, By Sir Andrew Ljungstedt, Knight of the Swedish Royal Order of Waza. A supplementary chapter, Description of the City of Canton, republished from the Chinese Repository, with the editor's permission, Boston, Jamers Monroe & Co., 1836 (2nd edition: Hong Kong, Viking Hong Kong Publications, 1992).

5 JESUS, Carlos Augusto Montalto de, Historic Macau: International Traits in China: Old and New, Macao, Salesian Printing Press - Tipografia Mercantil, 1926 [reprint: Hong Kong - New York - Melbourne, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press 1984], pp.68-69.

6 LEE, P. C., op. cit., p.153.

7 BATALHA, Graciete Nogueira, «澳門地名考»(Place Names of Macao), in ("Review of Culture", Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, (1) April-May-June 1987, pp.7-14, pp. 11-12 [Chinese edition]; BRAGA, José Maria, The Western Pioneers and their Discovery of Macau, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1949, p. 102;

8 Ibidem., p. 102.

9 WILLIAMS, S. Wells, The Middle Kingdom, 2 vols., New York, 1907, vol.2, p.428; BOXER, Charles Ralph, Seventeeth Century Macao in Contemporary Drawings and Illustrations, Hong Kong, Heineman Ediucational Books, 1987, p.14; BOXER, Charles Ralph, 1963, The Great Ship from Amacon, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos, 1963, pp. 87, 88, 90, 95, 100, 309.

10 BRAGA, José Maria, op. cit., p.102.

11 HUANG Shaochang 黃紹昌 - LIU Xiaofen 劉熽芬, «香山詩略» (Macao Poetry), Macau, (8) 1937, p.230.

12 GUO Fei 郭棐, (Emperor Wanli's years) «粵大記» (Guangdong Chronicles); «廣東沿海圖 » (Atlas of Guangdong Coast), p.36.

LJUNGSTEDT, Anders, op. cit., pp.11, 15, 21; BRAGA, José Maria, op. cit., p. 104.

14 PIRES, Benjamin Videira, SU Qin 蘇勤, trans. «蘇勤» (Converging of Ways: Cultural Intermingling), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1992, pp.74-75.

15 LIU Z. Y. 劉俊余 - Wang Y. C. 王玉川, trans., 1986, (Matteo Ricci: The History of a Missionary in China), Taipei Kwang Chi - Fu Ren University, vol.1, p. lll.

16 BATALHA, Graciete Nogueira, op. cit., p. 10.

17 ZHENG He-sheng 鄭鶴聲, «近世中西史日對照表»(Dates in Sino-Portuguese History), Zhonghua Shuju, 1981, p.601.

18 LJUNGSTEDT, Anders, op. cit., pp.156-158.

19 WANG Y. S. 汪慵叟, «澳門雜诗» (Macao Miscellaneous Poems), Macau, 1918, p. 10.

20 ZHENG W. M. 鄭煒明 «葡占tam仔路環碑銘楹匾匯編» (Collection of Couplets, Tablets & Scrolls in Portuguese Occupied Taipa and Coloane), Macau, 1993, p. 130.

21 CHEN G. Q. 陳國強, ed., «媽祖信仰與祖廟 » (Mazu Belief & Ancestral Temple), Fujian Education Publishing House, 1990, p.32.

22 BATALHA, Graciete Nogueira, op. cit.,

p. 12.

23Macao in 1839: Diaries and Drawings by Auguste Borget, in "Review of Culture", Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, (10) June-July-August 1990, pp.106-118, p.110 [English edition].

24Macao in 1839: Diaries and Drawings by Auguste Borget, op. cit., ill. p.117; 19th Century Macao Prints. Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1990; Historical Pictures, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Museum of Art, 1991, ill. p.64.

25Ibidem., p.69.

26 PIRES, Benjamin Videira, in 百年 華人區" ("Review of Culture", Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, (7 -8), October 1988 - March 1889, pp.46-53, p.51 [Chinese edition].

27 WEI Q. X. 魏青心, 1991, Huang Q. H 黃慶華, trans., «法國對華傳教政策» (French Missionary Policies Towards China), China Academy of Social Sciences, p.303; (Extracts from Jules Itier's Travel Diary), in ("Review of Culture"), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, (11-12) September 1990 - February 1991, pp.66-78, pp.75-76 [Chinese edition] -Also in the "Review of Culture" (11-12) September 1990 - February 1991, pp.80-92, pp.89-92 [English edition].

28 XU X. 徐新 (Interview), CHEN S. R. 陳樹榮 - HUANG H Q. 黃漢强, ed., in «林則徐與澳門» ("Lin Ze-xu and Macao"), p. 183.

29 XU S. F. 徐朔方 (Proof-read), 1982, «湯顯祖詩文集» (Selected Works of Tang Xianzu), vol.1; «玉茗堂詩集» (Selected Poems of Yu Ming-tang), vol.6, p.428.

30 QU D. J. 屈大均, «廣東新語» (New Sayings of Guangdong), Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 1985, vol. 18, p.481.

31 ZHU J. Q. 朱杰勤 1984, «中外關係史論文集» (Selected Essays on the History of China's Relations with Foreign Countries), Henan People's Publishing House, p.53.

32 'Jiuzhou' is translated from Malay 'Sembilan', referring to the group of islands off the coast of the Malay peninsula.

33 YIN Guangren 印光任 - ZHANG Rulin 張汝霖, The Portuguese in Macao, in «澳門紀略» ("Monograph of Macao"), Jiaqing reign, year 5, part.2, p.31.

34 LEE P. C., op. cit., p.173.

35 LIANG Q. H. 梁喬漢 «港澳旅遊草» (Touring Hong Kong and Macao), Guangxu reign, year 26, p.10.

36 ZHANG W. Q. 章文欽 «澳門與中華歷史文化» (Macao and the Historical Culture of China), Macau, Fundação Macau, 1995, p. 190.

37 YIN Guangren - Zhang Rulin, op. cit., p. 24.

38 WANG S. Z. 王士禎, «義松堂遺稿», Guangxu reign, year 20, vol.21, p. 12.

39 LEE P. C., op. cit., pp.139-140.

40 LIAO C. L. 廖赤麟, «湛華堂佚稿», Tongzhi reign, year 9, vol. 1, p. 15.

41 YIN Guangren - ZHANG Rulin, op. cit., p.29.

42 WANG Y. S., op. cit., p.8.

* BA in History from the University of Zhongshan, where he presently is an Associate Professor. Member of the Association of Chinese History of the Pacific Area, and of the Association of History of Guangdong. Author of Notes and Commentaries on Poems about Macao and Documentation on the History and Culture of Macao. Editor of the following publications in Chinese: William C. Hunter, The Fan Kwae at Canton: 1825-1844, Taipei, Ch'eng wen, 1965; and Bits of Old China, Taipei, Ch'eng wen, 1965; Anders Ljungstedt, An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China & Description of the City of Canton, Boston, James Monroe & Co., 1836 [1st edition]; and Hosea Ballou Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company trading to China: 1635-1834, Taipei, Ch'eng wen, 1966.

start p. 63

end p.