"Daosim played a major role in China's religious history in the first centuries of our era, both on its own and in relation to Buddhism."

(MASPERO, Henri, Le Taoisme, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1967 [reprint].)

San Xing Gold.

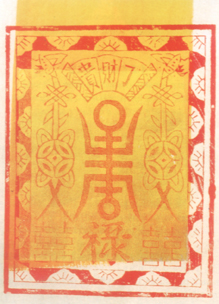

The three images correspond to the so-called San Xing 三星 — The Three Stars-- which correspond to Fulushou 福祿壽, the Daoist divinities of Fu 福 (Happiness), Lu 祿(Prosperity) and Shou 壽 (Long Life).

San Xing Gold.

The three images correspond to the so-called San Xing 三星 — The Three Stars-- which correspond to Fulushou 福祿壽, the Daoist divinities of Fu 福 (Happiness), Lu 祿(Prosperity) and Shou 壽 (Long Life).

§1.

Gift giving, if it requires reciprocity, has always been a way of maintaining relations with other people. The Chinese believe that there are both feared spirits (gui· and fan [ sic; hun· ?]) and respected spirits (such as the shen· and the protective pusa·) in the supernatural world. We must acknowledge these spirits when we have good fortune and pay homage to them, through respect and veneration, in case of misfortune, which is considered the result of not giving enough gifts to maintain the balance essential to a tranquil life.

At the end of the Han· dynasty (third century AD), the greatest ambition of the followers of the Way or Path was to become members of the 'Communities of the Great Celestial Masters', so that their name could appear in the transcendental world of the immortal. According to Chinese sources, it was during the Six dynasties·(AD220-589) that the expression "[...] to obtain a life and receive a destiny [...]" appeared in classical Chinese texts. This very ambiguous expression is related to the search for immortality, but it apparently had nothing to do with the notion of purchase or trade that became associated with it. In fact, it seems that, initially, it was associated only with the meditative practices that were so important to Buddhists and Daoists.

During both the Han dynasty and the Six dynasties, obtaining life was considered a conscious act, a religious act that continued in the Hereafter, through spiritual activity. This concept was limited to the intellectual world of the learned; however, with time it was introduced into popular thought. What emerged as a result was a theoretical world where the spirit of someone who died continued to live, thanks to the funeral ceremonies organized by the descendants, in which Buddhist monks and Dao masters played a significant role.

It is believed that the ritual of early repayment became widespread in South China at the beginning of the twelfth century, through the influence of Daoism. This may have been because of the spatio-temporal context that developed in China as a result of the organization of trade supported by the banking industry, which at the time relied on a lending system. The idea of a life debt, a debt contracted before birth as a result of the first rite of passage — the act of being born —was thus added to the concept of obtaining a life in the Hereafter, and it culminated in repayment offerings and all the complex beliefs related to the Transcendental Treasury, an idea that was older and more foreign because it was already discernible in the Sutras. These ritual repayment ceremonies were to be amplified at the time of death in order to settle the accounts of the life tax, so that life could be prolonged in the Hereafter. This led to the creation of bundles of paper coins symbolizing cash of different colours (and values), and of gold and silver ingots that are still burned in Macao at all Chinese funerals. The amount of the debt, which is really a means of paying for the right to be born and, consequently, to live, depends on the moment of birth and is related to the notion of minglu•1 which in turn implies the idea of 'fundamental destiny', an imperfect translation of benming. ·2

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

It is believed that it was to modify the negative aspects of this inexorable destiny determined at birth that Daoists created offering coins (probably in the third century). These imitated real cash and were first reproduced in clay then in bronze. It was generally accepted that by offering these coins one could set up a lending or taxation arrangement, a true compromise with the forces of the Hereafter that influence each person's fundamental destiny. When paper was invented, these coins were cut out of paper, and large bundles of them were used in all funeral rituals. Today, the significance of these ritual offerings of paper coins of different colours and of gold and silver paper money has been lost, as has the significance of the clay and bronze coins, which were used to ensure a favourable destiny.

These destiny coins were still used in Macao in the 1960s and 70s by conservative Chinese women who practised a form of Buddhism-Daoism that, philosophically, was very simple. These women were devout merely because they had enculturated inherited ideas, perhaps ideas that simply are, and did not question the practices that gave their soul strength so that they could resist all misfortune and live serenely (though not necessarily happily), which is the fundamental objective of the Chinese.

Today paper coins3 are burned in the most diverse rituals, but the old bronze coins are still used as amulets and/or talismans. The Chinese believe that if they are worn around the neck or the waist they protect people from illness, falls and fright provoked by malevolent spirits, acting in accordance with their minglu. They also guarantee health, greater longevity and peace, and orient the fundamental destiny. According to some authors, 4 early repayment, although practised during a person's lifetime, may be considered a funeral rite because it tends to facilitate life in the Hereafter.

From the fourth century on, South China was populated by successive waves of immigrants displaced from central China. It was mainly in Fujian· that the displaced Han populations, isolated by the characteristic geography of the southern provinces, preserved their cultural traditions, contrary to what happened in the North, which was swept by successive waves of armed invasions.

In Macao, then in Hong Kong and Formosa (Taiwan), the Fujianese and the Guangdongnese, as well as other Chinese, who were politically isolated, managed to preserve ancient customs, including their religious practices, which we were still able to witness and study in the 1950s and 60s. The most visible aspect of those practices is undoubtedly the burning of gold and silver papers that are sold in large bundles in specialty stores, usually folded in the shape of the valuable ingots that were formerly used as currency, and stacked up and tied with a red string.

§2. PAPER COINS, AND GOLD AND SILVER INGOTS

Paper coins, as well as gold and silver ingots, and even strips of plain or coloured rice paper with arabesques produced with more or less rudimentary xylographic techniques are also used in ceremonies dedicated to the hungry souls, the feared gui. This practice was influenced by Buddhism. The rice paper represents pieces of silk, one of the most sought-after offering materials, which used to serve as a form of tribute.

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

Paper money is not burned indiscriminately just anywhere, as an uninitiated observer might think. The money that is burned in tripods or incense burners inside temples or on home altars is meant for the major divinities, ancestors and the protective divinities in general. The money that is burned outdoors, in paved areas or on the land itself, is for the more feared divinities and the fan [hun ?], which are malevolent spirits (corrupt emanations and evil airs), as well as for the wandering souls, the ever popular but feared gui.

The gold and silver papers sold in ingots consist of a tin-plated square or rectangle, either printed or plain, that is applied to a sheet of pagoda paper5 measuring anywhere from 4.3 cm x 3.2 cm to 12.0 cm x 11.0 cm. There are different types of gold paper, or jinzhi,· also known as shoujin· (the gold of long life), as well as different types of silver paper, or yinzhi· (the silver of long life) also known as lianhuayin· (the silver of the lotus flower).

The size of these papers and the complexity of the xylographic design (or lack of it) vary according to the divinity to whom the papers are offered and the purpose of the offering. The biggest and most elaborate gold papers, for example, are offered to the Supreme Divinity, the Yudi· (Jade Emperor) himself. The lower the divinities are on the hierarchy, the smaller the papers offered. Papers offered to the tutelary spirits of the sun and other minor divinities, for example, never exceed 3.1 x 2.5 cm.

The most valuable gold papers usually feature the image of the triad known as San Xing· (the Three Stars) which correspond to Fulushou, • the Daoist divinities of Fu·(Happiness), Lu· (Prosperity) and Shou· (Longevity). 6 In this group of three figures, the middle one is represented as a magistrate Tian'guan· (the Celestial Magistrate), usually holding a sceptre or a roll on which is written the word "happiness" or the following auspicious words: "Tian'Guan Cifu"· ("The Celestial Magistrate Confers Happiness"). To the right of this magistrate is Lu, an emblematic figure holding a child in his arms who, according to popular belief, corresponds to Wen, ·the famous Western Zhou· king (°1122-†770BC) who had numerous descendants. 7 To the magistrate's left is Shou Xinggong, · who has a deformed head and promotes long life. He is often portrayed holding a peach in his hand, and he has a staff from which a gourd is suspended. 8 This figure seems to have been inspired by the classic Xiyouji· (Pilgrimage to the West) according to which Shouxing· (the Star of Longevity) carries cinnabar pills in a gourd. To Daoists, cinnabar is the ultimate transcendent substance.

Cover sheet of a yingzhi 銀紙 (silver of long life) bundle.

Cover sheet of a yingzhi 銀紙 (silver of long life) bundle.

Because the words for fu· (bat) and die· (butterfly) are homophones of 'happiness' and 'seventy years of age' (first longevity), respectively, images of bats, butterflies or other symbolic elements usually accompany, or even replace, the Sanxing figures that correspond to them. Quite often, only the three pictograms are xylographed on the papers. Because their sides are usually cut at a right angle, gold papers are known as gold stamps or gold seals, which gives them a special power since the imperial gold seals, and even the Mandarin seals, help keep demons away.

Instead of being burned, gold papers with figures of the triad or corresponding symbols may be used in funerals to cover the face of the deceased, like a mortuary kerchief, in order to protect the person from evil influences on the journey to the Hereafter. Except in this special case, these papers are not used in funeral rites. In fact, they are used mainly by mediums, to make their spirit return after the possession and/or to heal wounds they may have suffered while in a trance. The purifying and prophylactic function of these papers is probably the most important. When burned in homage to the Tian'gong· (Lord of Heaven), they serve to purify the legs of the tables used in rituals, but the same effect can be obtained by simply placing the papers on the table legs. In Macao, in the sixties and seventies, imagemakers whose shops were located in the Bazaar on Rua da Madeira [Wood Street] commonly used the smoke produced when the papers were burned to purify the wood from which statues of divinities were sculpted.

Cover sheet of a yingzhi 銀紙 bundle — another kind.

Cover sheet of a yingzhi 銀紙 bundle — another kind.

Yinzhi 銀紙 (Silver of long life) Obverse of a bundle's paper coin sheet.

Yinzhi 銀紙 (Silver of long life) Obverse of a bundle's paper coin sheet.

Paper with figures of the triad was also burned for the passage over fire, a purification ritual practised in Macao up until the 1960s. At traditional weddings, the bride passed over the flames when entering the house of the groom's family. This ritual was also part of the festivities that marked the anniversary of a divinity. Gold papers with the Daoist triad were also used in Macao when jing Tian'gong· (worshipping the Lord of Heaven), at weddings, when celebrating the anniversaries of the head of the family, and to mark joyous occasions. These papers are the most valuable, along with the huaqian· (coins featuring flowers).

Aside from gold papers featuring the triad, there are (as mentioned earlier) others of lesser quality that are burned in large quantities every day, in all types of rituals, to pay homage to the divinities of the Hereafter that protect mortals. That is why these gold papers are known as 'the gold of longevity'. Like coloured rice papers, gold papers with xylographed floral designs represent pieces of fabric, but in this case the fabric is gold brocade, which is more valuable than silk.

In the 1960s and 70s, six varieties of plain gold paper (without any inscription whatsoever) were sold in Macao. They were available in different sizes and quantities. Some ranged from 1.0 x 1.5 inches (2.3 cm x 3.6 cm) to 3.5 x 6.0 inches (8.7 cm x 14.9 cm) and were sold in batches of thirteen to thirty five units. The most popular was the fujin, · which was to be burned in honour of Tudigong· (Divinity of the Soil). These papers were burned to pay homage to the tutelary spirits of each place (including the place of residence) and to, Caishen· (the Spirit of Wealth).

The first offering to Tudigong was made each year on the second day of the first moon. Other offerings were made throughout the year, mainly on the fifth day of the fifth moon Jiri· (the Very Auspicious Day) and on chuxi· (New Year's Eve). 9 In Macao, in the 1960s and 70s, it was common to see women with trays of offerings burning votive papers on the street in front of the doorways of houses, and lighting candles and sticks of incense that were imbedded in the sidewalks or inserted in cans that had been painted red.

The smallest gold papers, ranging in size from from 1.0 x 1.5 inches (2.3 cm x 3.6 cm) to 3.5 x 6.0 inches (8.7 cm x 14.9 cm) and available in stacks of twenty five units, were known as xiaojin· (small gold). Used in exorcistic practices, they were also offered to the feared spirits, the spirits of the dead and wandering spirits, which were generally associated with silver papers. As in the past, they are still burned on the land and are associated with the xiaohun· (Three Small Animals), represented by an egg, a piece of fish and a piece of bacon, which are placed in three plates lined up in front of three teacups.

As for silver papers, two sizes were sold in Macao: 2.0 x 2.4 inches (4.6 cm x 5.5 cm) known as xiaoyin· (small silver) and known as 3.5 x 4.3 inches (8.7 cm x 10.4 cm) dayin· (large silver). There were three varieties of each, depending on the shape and decoration of the tin-plated rectangles. The hierarchy of the recipients of silver papers is similar to that for the gold papers. However, the decoration of silver papers is limited to a drawing of a lotus flower, which appears only on large papers. Buddhist in origin, the lotus represents purity and is the seat of its divinities. It also symbolizes reincarnation, which explains why silver papers are used in ancestor worship, and expresses the wish that the shen (ancestors) will reside in the Hereafter (the Western Paradise of the Daoists).

Lian huayin 蓮花銀 (silver of the lotus flower).

Lian huayin 蓮花銀 (silver of the lotus flower).

Married women offer their husband's ancestors silver lotus papers, but never gold ones. This is because silver is the colour of the moon, and along with gold, the colour of the sun, these celestial bodies symbolize yin· and yang, · respectively, which correspond to the feminine and masculine principles.

The Chinese believe that shen who receive offerings from family members on a regular basis obtain ling· (spiritual power or essence), and can thus protect their family members from the Hereafter. Silver paper is used in funeral ceremonies, in ancestor worship, and in the worship of wandering souls, of the spirits of the first occupants of a place and of the spirits of people who died a violent death. 10

A large piece of silver paper is burned at the entrance to the house when someone dies, in order to light the way to the Hereafter. To pay the cost of the journey, the family burns silver paper from time to time until the day of the funeral, and the coffin is also filled with stacks of large pieces of silver paper and gongqian· (Celestial Treasury coins). Silver paper is also burned at the end of funeral ceremonies.

Every seven days, 11 a ceremony must be held to pay tribute to the departed. During the ceremony, which may be held at home or in temples, various paper objects are burned, representing items of clothing, furniture, trunks full of clothing, gold and silver plates, fully furnished houses, a couple of servants, etc. However, the most precious of all these valuables were silver papers and Treasury coins.

The cult of the first occupants of a place was very common in Macao, especially in the Hortas do Istmo area, but only among rural immigrant families. The ceremonies took place on the second day of the second moon, during Qingming. ·12 and on the sixteenth day of the twelfth moon. The recently arrived occupants feared retaliation from the spirits of the former occupants if they did not celebrate these rituals when they were working land that had been enriched by the former occupants, who sometimes had to make a considerable effort.

With respect to Treasury coins, it is believed that as early as the Neolithic period cowrie shells —which were used as currency at the time —, or a reproduction made of bone or stone, were buried with the dead in China. 13 The reason for placing cowries in the grave is not known, but it is assumed that this practice served some religious purpose. Perhaps the shells were merely barter material for the journey to the Hereafter.

The custom of placing cowries (which were perforated and strung, as was later done with cash), grains of rice, or precious or semi-precious stones in the mouth of the deceased is mentioned in the famous Liji· (Book of Rites). 14It was most popular around 1000BC, during the Western Zhou Dynasty. Curiously enough, it has prevailed until modern times among rural populations, so strongly do they believe that it benefits the departed and their families.

Metallic coins appeared only in the time of Zhou Zhao, ·in various forms. 15 Cowries, which at first were used simultaneously with coins, were progressively substituted by so-called guitou qian· ('Devil's head') coins, which were bronze reproductions of the valuable shells.

Lian huayin 蓮花銀 (silver of the lotus flower).

Lian huayin 蓮花銀 (silver of the lotus flower).

In the spring of 1972, the opening of the famous tomb of Dai Houqi· (Marquise of Tai), dating from the first half of the second century BC, revealed large quantities of clay coins, along with many valuables. 16 According to the bamboo tablets recovered from the tomb, on which the objects that had been buried were listed, both the clay coins and the reproductions of gold plaques were known as jinqian· (gold coins, meaning, money), which leads us to believe that the offerings served a religious purpose and not a socioeconomic one. This practice continued throughout the centuries that followed.

During the Six dynasties, the placement of real or imitation coins in tombs became much more rare. According to some authors, this was because the coins started to be reproduced in paper. In the first half of the seventh century AD various types of paper money were already in use in China, as is recorded in registers such as the famous Ming Bao Ji · from the Tang· dynasty.

Apart form the Celestial Treasury coins or gongqian used in funeral ceremonies, there are coins used to pay the debt of having acquired the right to be born and to live. They are represented by the paper money that is very often burned to pay homage to all the divinities.

§3. COINS USED IN FUNERAL RITUALS

In Macao, the coins used in funeral rituals were sold in bundles of twenty eight to one hundred sheets with six to thirty wavy incisions, each of which represented a string of cash. They were offered to the 'officers of the Celestial Treasury', to pay the debt of reincarnation, but they also served to ensure the tranquillity of the ancestors in their new life in the Hereafter.

The second type of Treasury coins were the benmingqian· (Fundamental Destiny coins), which were distinguished from the previous ones by the fact that its packaging had a tin-plated gold or silver paper on it. The ones with the gold paper were for the Celestial Treasury and those with the silver paper were for the Terrestial World, the Treasury of Hell.

The notion of Fundamental Destiny, which some authors translate as "fate", is quite complex. If a Daoist priest is asked what its significance is, his answer will be so vague and transcendent that it will be impossible to interpret. It is generally accepted that benming corresponds to the idea that each person receives a ming from Heaven, the word ben· (to be born, to emerge) corresponding to 'individual', 'personal' or 'fundamental'.17

According to the more simplistic Daoist notions, the term pun meng is used to designate the four elements that define a person's date of birth: year, month, day and time. In Daoist texts, this expression is also applied to certain divinities and is used to define places, directions, rituals and offerings. That is why its philosophical concept is so complex.

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

Obverse of a bundle's paper coin sheet, displaying representations of fu 福 (bat) and xi 囍 (double happiness).

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

Obverse of a bundle's paper coin sheet, displaying representations of fu 福 (bat) and xi 囍 (double happiness).

In the 1960s, two types of metallic coins were still sold in Macao for ritual or magico-religious purposes: those that were used for payment (equivalent to a life tax) and reproductions of bronze coins and pendants, which were already difficult to obtain but had once served as offerings in the fundamental destiny rituals, to ensure a happy life. They were used to shape destiny through purchase, or better yet, through trade, being a reciprocal gift to the divinities that oversaw the destiny of individuals.

Five examples of these bronze coins have survived. Used as amulets and talismans, they were worn around the waist or the neck, and were sought by people who suffered setbacks or whose fate did not seem favourable. People often offered them to friends who were experiencing difficult times, as proof of their esteem. The use of these coins dates from ancient times in China, and they were adopted by Buddhists and Daoists for the same purpose.

According to Daoist texts, written prayers known as zhang· were used to cure illness. They were equivalent to the fu· used today — papers with hermetic phrases to be pasted on houses or to be burned and the ashes drunk. When addressed to the divinities, these prayers were to be accompanied by offerings of silk, coins and rice. At the end of the ceremony, the officiating priest kept three-tenths of the offering, and the rest was distributed among the community's poor.

The value of the offering had to correspond to the social standing of the person making it. In earlier times, common people had to offer only bronze coins and ordinary silk, whereas men of high standing had to offer fine silk and silver coins, and the imperial family had to offer rolls of purple silk and gold coins. The silk offered by men of high standing and common people also had to feature the five colours of the rainbow meant for the Five Emperors of the Five Regions. Another piece of silk had to be added to these; its size was proportional to the age of the person making the offering and its colour was defined by that person's date of birth. With time, people started reproducing the offerings on paper, although those who were more credulous continued to use bronze coins as amulets, as a means of guaranteeing a happier life.

Ancient amulets such as bronze mingqian· (destiny coins or life coins) often have one of the following inscriptions: "Benming xingguan"· ("Star (or Stellar) Magistrate of Fundamental Destiny") or Benming yuanshen· ("Primordial Spirit of Fundamental Destiny"). Besides this inscription, there is a representation of the respective stellar divinity in Mandarin dress or the shi'ershou· (Twelve Animals) of the duodenary cycles — or perhaps only one of them — which corresponds to the old coins of the dizhiqian· (Twelve Terrestrial Branches coins) of the Animals associated with the shengxiaoqian· (birth sign of the person for whom the coin is meant). One or more motifs are engraved on the reverse of these coin amulets. Examples are:

Shoujin 壽金 (Gold of long life).

1. The seven stars of Ursa Major, which gives the coin its name, bidouqian· (Ursa Major coin), 18

2. A turtle, a snake and a pair of swords, the emblem of the God of the North Pole, which corresponds to Ursa Major, the symbol of strength and power.

These coin amulets were used in large numbers starting in the Song· dynasty, and today all good books on Chinese numismatics have a chapter on them. 19 The coin that is considered the oldest Chinese coin amulet was found in China in 1965, in the Yiyang· district, in Henan. · It is round with a square opening in the centre, each side of which measures one centimetre. The anthropomorphic decoration of the coin dates to the Han dynasty. The fundamental destiny coin amulets used today seem to be the result of a long evolution that occurred mainly in the Song dynasty.

The following is a description of the five coin amulets we acquired in Macao (four were purchased and the other was a gift).

4.1 COIN NO.1

This coin is shaped like a bronze gong with a 3.6 cm diametre. Ideograms are inscribed within a small circle on the obverse, the centre. The ideogram for "fu"· (happiness) appears above this circle and the one for "xi"· (joy) appears below it. Shou Xing Gong, · a symbol of long life, a bat and a female fallow deer, symbols of happiness and prosperity, are represented on both sides, in relief. These three symbols represent the Fu, Lu, Shou = San Xing (Three Stars) triad of the most valuable gold papers described earlier. The following is written on the reverse of the coin: "Wuzi dengke fushou shuangquan"· ("Five sons manage to become magistrates; happiness and long life together").

4.2 COIN NO.2

This circular coin with a 3.6 cm diameter, has a square opening in the middle, each side of which measures 1.0 cm. On the obverse, around the edge, there is a double volute, a very old motif that was used on Neolithic vases and on bronzes from the Archaic period. Four stylized butterflies, symbols of long life, and two bats, symbols of good fortune are also represented. The reverse of the coin has the same border and features the bagua· (the ultimate demonifuge) and the cyclical symbols corresponding to diagrams with the following names: "qian",· "dui",· "kun",· "li",· "xun",· "zhen",· "gen"· and "kan".· In the middle there are four ideograms forming the auspicious phrase: "Kaiyuan tongbao"· ("Open the system for the use of coins"), which is a wish for prosperity, since this coin is a reproduction of the oldest coin minted in China. 20

4.3 COIN NO. 3

This coin with a 4.0cm diametre, has a circular perforation (1.0cm diametre) and a plain edge. Two human figures and a lingzhi· (fungus of long life), are represented on the obverse. The figures must correspond to the Celestial Magistrates of Fundamental Destiny. On the reverse there are also two human figures, one of which is on horseback and has the insignia of a military chief (a helmet with two pheasant feathers). One of the figures seems to be defending himself from the other, who is attacking him. Was this coin used as an amulet to keep away the evil influences of the enemy? Or was it an amulet used in war?

4.4 COIN NO. 4

This coin has a 3.4cm diametre and a square perforation (each side of which measures 1.0cm). The stylized figures represented in relief on the obverse are apparently fighting. The reverse has the following in old-style ideograms: "feng"· ("wind"), "hua"· ("flowers"), "yun"· ("cloud") and "yue"· ("moonlight"), which is equivalent to a wish for good weather, good scenery and good prospects throughout the four seasons. It is assumed that this is an incantation for protection against curses.

4.5 COIN NO. 5

This small octagonal pendant, each side of which measures 1.2cm, has a perforation near one of the edges, rather than in the middle, so it was probably suspended from a string. The obverse features the eight trigrams with their respective cyclical symbols and, in the middle, the taiji, · the symbol of cosmic duality, of perfect balance. The following is written on the reverse: ("The Divinity (the Supreme Lord) ordered that all wandering spirits be killed, that all evil spirits be warded off and that (the person who possessed the coin) always enjoy good health").  This is the talisman a Chinese friend gave us.

This is the talisman a Chinese friend gave us.

In conclusion, it should be noted that it is not only special coins or pendant reproductions of ancient coins that are valued as amulets. Ordinary copper alloy coins known as cash, which were common in the past, are still used as amulets but mainly by the seafaring population.

§4. CASH AS AMULETS

Cash no longer serve as currency, but in the past they had the most diverse uses, and today children still wear them around their necks as amulets. The so-called dikouqian, · cash that were placed in the mouth of a deceased person at the time of burial, are reputed to be very effective against evil, as are the nails used in coffins.

Bailaoyeqian· (Bailaoye cash), that were kept by the more conservative Chinese women as precious treasures, are still greatly valued. In the procession that was held in honour of Chenghuang,· the divinity that protects the city and whose chapel is in Mong Ha· next to the Guanyin Miao· (Kun Iam Temple), the person who played the role of Bailaoye carried cash between his teeth. This ritual was not included in the procession held in Macao (although Chenghuang was worshipped there), but only in villages in the interior of China. This cash was in great demand among the devout, who believed they offered protection against the influences of evil spirits. The coins were obtained from strangers or through family members. Since these processions are no longer held in China, these coins are becoming more and more rare, and are considered real treasures.

For protection against the spirits of childhood diseases, provoked by the spirits of women who died childless, Daoist priests threaded cash from various past dynasties on thin bronze cylinders or (in more recent times) cylinders made from strong wire, and then tied them together with a red string to form a sword. These swords, which usually consisted of twenty one cash, were placed in the rooms where the children slept or next to their beds, along with other cash arranged to form a sphere, a flower from a plum tree or even small jade amulets shaped like teardrops.

These cash swords or sabres, known as Zhongkui zhijian, · represent the magic sabre of Zhongkui, · a famous exorcist and one of the eight Daoist immortals. They are used as amulets to keep away evil spirits. In the past, however, they served specifically to protect children because of the high incidence of infant mortality. They were also used much more widely as magic charms.

When a member of the family became ill and developed a fever, a cash sword was placed over the door of the residence to keep the evil spirit causing the fever from returning. The cash that were considered the most effective for making swords were those dating from the glorious periods in China's history, mainly from the Qianlong· (°†1736-†l796) reign, an emperor of the Qing· dynasty and fervent Buddhist who had many temples built and started the cult of many new divinities.

Cash could also be used in other ways, especially if it had been recovered from a tomb or possessed ling· (spirit), due to its age. Various examples of their former use as charms are known, a use which is currently disappearing. In Macao, in the 1960s and 70s, Zhaolingqian· were still highly valued. This name refers to the real cash that is normally placed on the four corners of paper houses usually burned after funeral ceremonies during each of the seven cycles of the forty nine days that follow a person's death. After the fire has consumed all the paper and part of the bamboo frame, women quickly stir the ashes in search of these coins, which are also considered excellent amulets. In the sixties, we witnessed this in Macao, in private homes in Mong Ha and even in western-style buildings occupied by Chinese people on Estrada da Vitória (Road of Victory).

The origin and finality of life are dramatic problems that give rise to the need for prophecy and religious thought. It is therefore not surprising that the same fundamental thoughts appear throughout the world. For this reason, of all the elements of culture, myth and religion, these are the most difficult to subject to logical analysis. Modern science has transformed mythical space into material space, but there are still many phenomena that are beyond the bounds of scientific rationality.

On the one hand, memory and imagination lead to the oral transmission of great successes that often result from circumstances that escape logical analysis. Beliefs and myths are transmitted from generation to generation, along with experimental knowledge, and they evolve through omissions, distortion or additions that alter the original idea. On the other hand, the concept of time is associated with human interiorization. As a result, since time bridges the past and the present, the most diverse superstitions are kept alive, even among highly educated people. Therefore, many practices whose survival over the centuries seems inexplainable can be logically justified if viewed as subtle ways of maintaining psychological balance, and re-establishing tranquillity and personal harmony.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Paula Sousa

山鬼

山鬼

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

|

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

Shan'gui

|

雷霆殺鬼降精

style="mso-spacerun: yes">

lang=EN-US style='font-size:12.0pt;font-family:宋体;mso-bidi-font-family:"Arial Unicode MS"'>

|

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> Leiting

shangui xiangjing

|

祈妖辟

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

|

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

Qi Yao bi

|

神请奉殺都永保

style="mso-spacerun: yes">

lang=EN-US style='font-size:12.0pt;font-family:宋体;mso-bidi-font-family:"Arial Unicode MS"'>

|

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> Shen qing feng sha dou yong bao

lang=EN-US style='font-size:12.0pt;font-family:宋体;mso-bidi-font-family:"Arial Unicode MS"'>

|

太上老君急急如令赦

lang=EN-US style='font-size:12.0pt;font-family:宋体;mso-bidi-font-family:"Arial Unicode MS"'>

|

Taishang laojun

jiji ru ling she

|

雷公

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

|

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

Leigong

|

See: SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY — for the following authors and further titles for authors already mentioned in this article.

BIOT, E., trans.; O Ceremonial (Li-Ky), original Chinês com caracteres e alfabeto, versão Portuguesa e notas críticas pelo Pe. Joaquim A. de Jesus Guerra, S. J. (Missionário de Shiu-Hing, Macau, China [ect.]; DAY, Clarence Burton; FUNG Yu-Lan; GRANET, Marcel; HOU Ching-Lan; LI Tsohien; MASPERO, Henri; WALEY, Arthur.

NOTES

1 Minglu (lit.: prosperity of life). The notion of the word goes beyond this simple concept, corresponding to the idea that it is Heaven that places each person in a particular social position and gives him or her a certain longevity. Thus prosperity is not based on merit but is determined by a superior entity.

2 Benming (lit.: to emerge from life). The word 'ben' ('to emerge' or 'be born') presupposes a notion of ascent or climbing, like the sun, which rises and pursues it path until setting. Therefore, the translation of the Chinese author Hou Ching Lang (1973) was adopted.

3 Paper money to be used as offerings beqian to appear during the reign of Tang emperor Xuanzong· (AD°713-†755). Its invention is attributed to Wan Yu. ·

4 HOU Ching-Lang, Monnaies d'Offrande et la Notionde Tresorerie dans la Religion Chinoise, in "Mémoires de l'Institut des Hautes Ètudes Chinoises", 2 vols., Paris, Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques - Presses Universitaires de France, 1975, vol. l.

5 Coarse paper usually made from bamboo.

6 Some Chinese believe that this triad corresponds to the spirits of Wealth, Long Lineage and Longevity.

7 According to other authors, this figure corresponds to the divinity that promotes Wealth.

8 Dao· (gourd) that used to hold medicine is a symbol of Health and Long Life, as is the peach, because its name is a homophone of Dao· (the Way or Path).

9 Tu Di is known by various names, which are engraved on stone stars found on small street altars in various places in Macao. These altars used to be very common in the peripheral areas occupied by vegetable gardens, where there was always someone to light sticks of incense. Of the local spirits, the best-known were Fude Zhenshen· and Fude Ci ·

10 In Macao, in the 1960s, most Chinese people did not distinguish these spirits from wandering spirits, including both in the group of the well-known gui.

11 The number seven, which is associated with the periods during which the soul supposedly returns to the world of the living before going to live in the Hereafter, corresponds to the number of garments the deceased wore. However, this number could vary according to the social standing of the deceased. Young people wore three garments, whereas elders wore twelve.

12 The Qingming (Festival of Pure Light), is one of the two great festivals held to honour the dead.

13 HOU Ching-Lang, op. cit., p. 3.

14Liji (Book of Rites ), which was published only during the reign of Qianlong under the title Imperial Edition of the Cerimony of the Rites with Notes and Explanations, was compiled by Confucius and his disciples in the sixth century BC.

15 The various forms of metallic coins.

16 In 1972, forty four boxes full of reproductions of metallic coins of the banliang· (half ounce) type were recovered, as well as a box of reproductions of gold plaques, with the inscription "yin jian".

17 HOU Ching-Lang, op. cit. p.106 — The author considers 'ming'·a synonym of 'sheng'· ('life' or 'birth').

18 Ursa Major is considered to be the constellation that indicates the North Pole and the centre of the universe, hence its great power as a force of evil.

19 These coins may date from earlier times in China because it appears that they existed in the Six dynasties period. In the Longmen· (Dragon Doors) caves, there is an expression that was common at the time and referred to a coin of "Happiness, Virtue and Long Life".

20 A copy of the examples from the first monetary system used in China.

* Ph. D. (Lisbon). Lecturer in Anthropology, Instituto de Ciências Sociais e Políicas (Institute of Social and Political Sciences), Lisbon. Consultant of the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation). Author of a wide range of publications dealing, primarily, with Ethnography in Macao. Member of the International Association of Anthropology and other Institutions.

start p. 79

end p.