Paul A. Van Dyke

* Ph.D. in History from the University of Southern California.

Doutor em História pela Universidade da Califórnia do Sul.

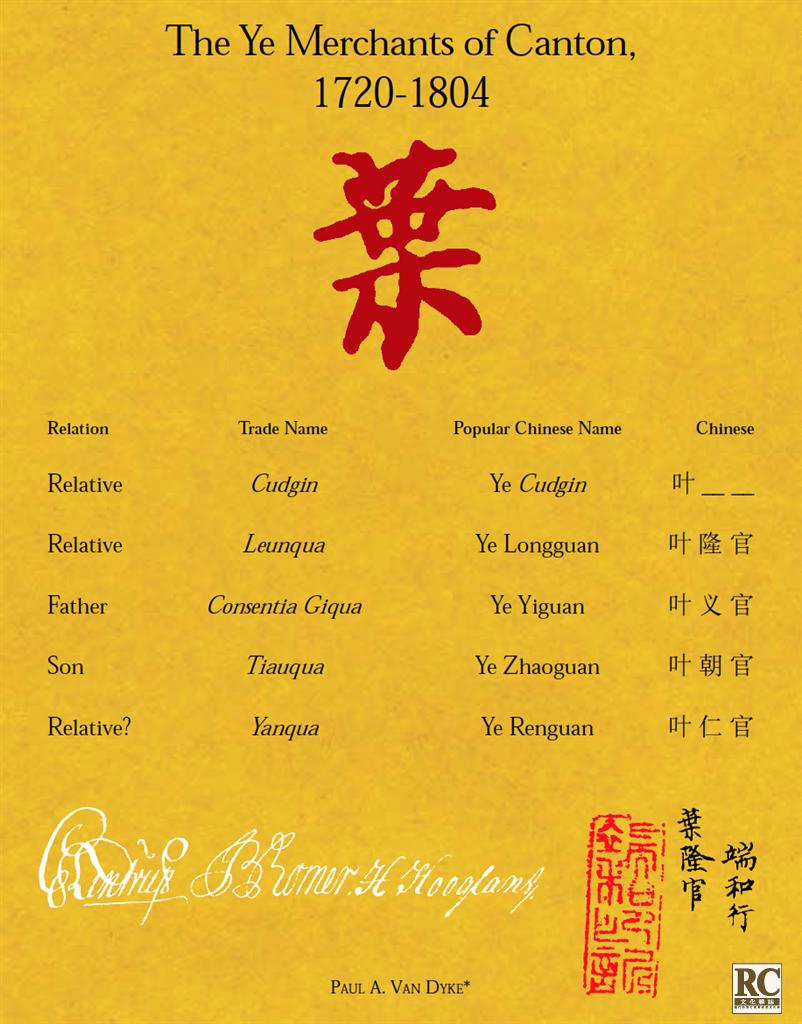

From 1720 to 1804 there were five merchants of the Ye family active in Canton: Cudgin, Leunqua, Giqua, Tiauqua and Yanqua. They dealt in all the usual products that Hong merchants handled, including tea, fabrics and silk, but some of them were especially focused on porcelain. Except for the first man, Cudgin, the other four Ye merchants were, for the most part, classed among a group we call “small merchants.” The large houses controlled much of the trade so these other men were often left outside of the decision making process of how the trade should be run. The Ye businesses on the whole were considerably less complex than those of the Yan 顏 and Pan 潘� families so they show us a different side of the story.1

Leunqua, Giqua and Tiauqua were much less aggressive in their practices than Cudgin and Yanqua. They were more inclined to do the best they could with the capital and resources they had on hand rather than borrow excessive amounts of money from the foreigners. They relied more on attracting patrons by offering good bargains. The three men do not seem to have been inclined to treat the foreigners to lavish dinners or accommodate them with lodging, which shows their thriftiness and sense of keeping expenses to a minimum. Nor do we have any references to these three men keeping their own agents in China's interior or in Southeast Asia, which means they probably did not buy directly from the sources but depended on middlemen to supply the goods they wanted. This is a very different picture from what we have seen in larger houses, so the Ye trade shows us an important side of the commerce that has been given little coverage in the past.

The other men, Cudgin and Yanqua, are two of the very few examples we have from this period of Chinese merchants actually being able to retire from the commerce. Both of these men managed to leave the trade with a sizeable fortune in their hands, which even contemporaries thought to be quite extraordinary at the time. Because their success is unprecedented in the historical literature, it alone warrants us taking a closer look at their lives so we gain a better understanding of the complexities of society and commerce in the delta. The story begins with Cudgin.

CUDGIN

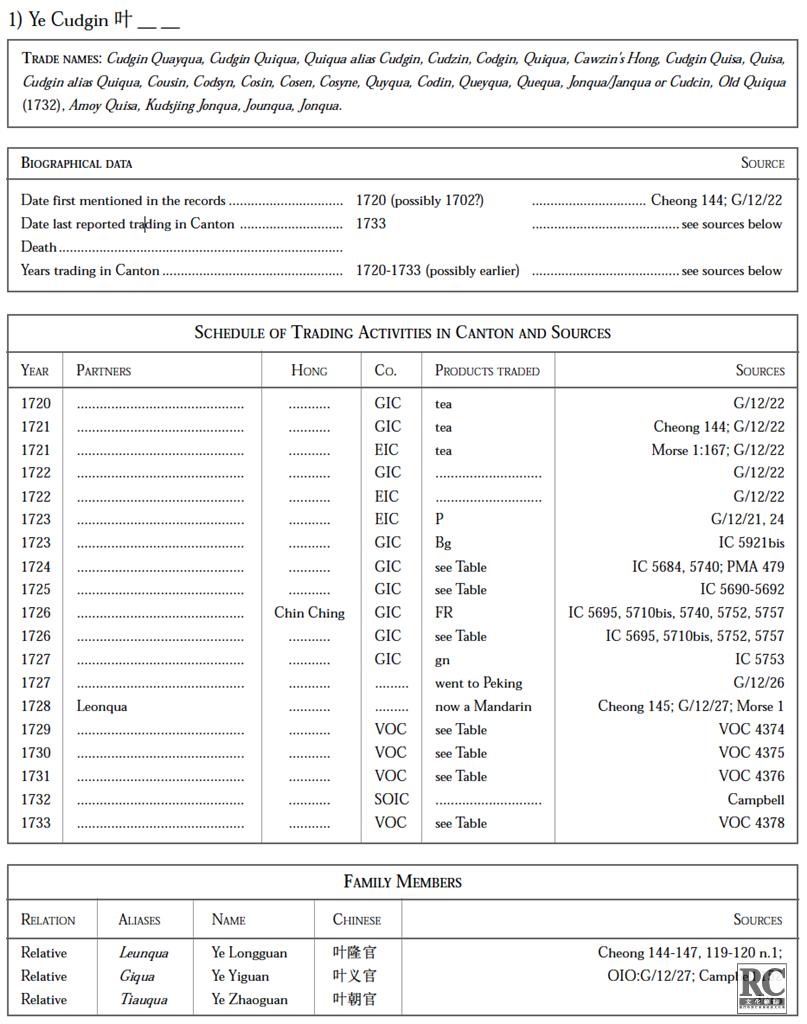

As far as can be determined from the foreignrecords, Cudgin was the first of the Ye merchants in Canton. Many of the records from the East India companies from the early eighteenth century are either missing or incomplete, and very few Chinese records of the trade have survived. Because of the sparseness of the literature, it can be very difficult to track down the Chinese merchants. In his study on the Hong merchants, W. E. Cheong suggests that the name “Cawsanqua” that appears in 1702 may have been Cudgin. Huang and Pang have also recently compiled a list of merchants' names that they found in the Chinese sources, and they list a merchant by the name of Ye Zhende Ye Zhende 葉振德�� in Canton in 1697. Unfortunately, there is no way of knowing whether either one of these two men has any connection to Cudgin.2

We know that Cudgin retired in 1732, but we do not know how old he was at the time. If he had been in his senior years (or at least in his fifties), which seems likely, then he could very well have been old enough to have been trading in 1697 or 1702. Because we have no references to a name like Cudgin in the years from 1703 to 1719, we have chosen to begin Cudgin's story in 1720. Beginning in that year, we have clear and consistent entries to him from which we can restructure his story.

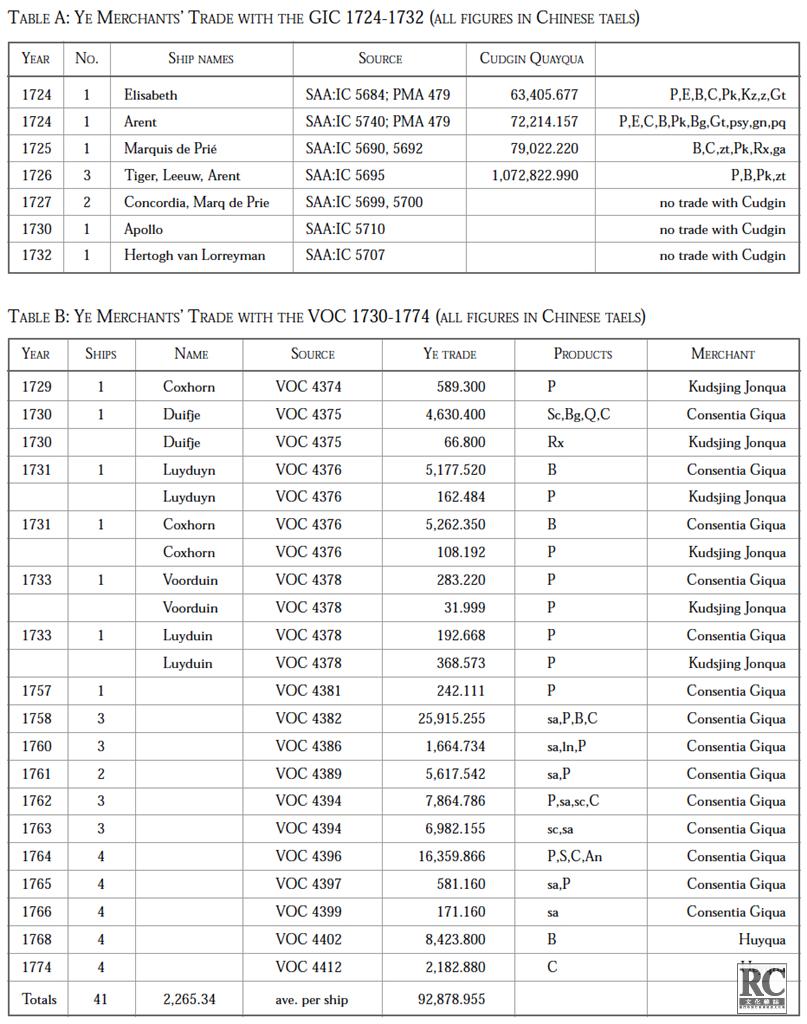

In 1721/1722, the English East India Company (EIC) supercargoes mention that they contracted with Cudgin and Suqua (Chen Shouguan 陈寿官), and that this was done because these two merchants had been trading with the Ostend Company (later known as the Ostend General India Company, GIC) for the past two years. The English hoped to woo these two merchants away from the Ostenders so that they could disadvantage them in the trade, and of course benefit the EIC in the process. The early Ostend Company records have not survived, so we are not able to cross-reference this entry, but the later GIC records do indeed list Cudgin as one of the merchants with whom the Belgians traded from 1723 to 1726 (see Table A). He shows up in many of the GIC records from this period as Cudgin, Cudgin Quiqua or similar spellings.3

A word should be said here about the different ways in which Cudgin is referred to in the foreign records because it has resulted in there being some confusion about his identity in both the primary and secondary literature. Because Cudgin later became a mandarin and was sometimes referred to as Quiqua, it has been suggested that the Hong merchant known as “mandarin Quiqua” was also Cudgin. This name, however, appears in the records before Cudgin ascended to that rank, and some of the foreign account books that have survived clearly list mandarin Quiqua and Cudgin separately, so there is no mistaking that they are different persons. There have also been some suggestions that the man known as “Old Quiqua” in the early 1730s (when Cudgin retired) was also Cudgin, but the Danish records show that this man was Chen Kuiguan 陳魁��官, with no connection to Cudgin. Because of these ambiguities, some of the references to Cudgin in the historical literature have him mixed up with other persons, so care needs to be taken not to repeat those mistakes.4

The 1720s were very precarious years in Canton for trade, which undoubtedly contributed to Cudgin's desire to retire from the business altogether. As was the usual practice at this time, after arriving at Macao in the fall of 1726, the GIC officers went upriver in order to negotiate the terms of the trade with the Canton officials and merchants before the ships arrived. It was important to keep the ships at Macao until all of the terms had been agreed upon as this gave the foreigners greater leverage in negotiating the freedoms that they wanted.

When the GIC officers arrived at Canton, they were not pleased with the news they heard. The foyen (governor, but in this case he was also called the viceroy) was demanding a 10 percent tariff on all silver that was landed that year, which was a departure from the way that the trade had been conducted in the past. There were good reasons for wanting to tax silver, but this practice was not common in other ports, so the foreigners were very reluctant to submit to this policy. The GIC supercargo Robert Hewer asked Cudgin and the other merchants to arrange an audience with the viceroy so that he could discuss this new stipulation and present their demands.5

While they were waiting for the day of the audience, Hewer secretly met with the merchants Suqua and Hunqua to try to negotiate an alternative in the event that he was not successful with the viceroy. He asked the two men if they would consider going to Amoy to trade. If they were willing do this, Hewer said he would dispatch a couple of the ships to that port instead of Canton. This was actually an old idea that Suqua had been entertaining for several years so it was well known that he had such intentions.6

In the meantime, the viceroy caught wind of the connivance. He immediately sent word to Suqua and Hunqua warning them that if he caught them undertaking such a bold venture as diverting the trade to another port, he would have them beaten with a bamboo and he would punish their families while they were gone. These threats put an immediate end to all thoughts of leaving Canton. Hewer now had no alternative but to wait to see what he could arrange with the viceroy.

The audience took place on August 18, and Cudgin, Suqua, Honqua, Cowle, Tinqua and Quicong accompanied Hewer and his officers to the viceroy's palace. There were about “3000 men” standing guard, and one of the chief mandarins took charge of officiating the ceremony. After the greetings and introductions, Hewer presented his demands and stated that he would not order the ships upriver unless he could be assured that the terms would be acceptable. During the meeting, however, Hewer suspected that the linguists, who were translating everything into Chinese for the viceroy, were not telling him everything. Nor were they representing the GIC as requested, so he turned to the merchants for help. Hewer mentions that the merchants “spoke English” (no doubt, Pidgin English), so he was able to speak with them directly, which was a great convenience. He asked the merchants to promise to make sure that the viceroy understood everything they demanded, which they consented to.

On August 22 Cudgin and the other merchants met with the GIC officers to deliver the viceroy's answer. The viceroy had not taken kindly to their request to land all of the silver duty free, but on the contrary announced that 10 percent would be charged on the money and that Cudgin would be held responsible for the total amount. This was not good news for the GIC or the Chinese merchants, but after discussing their alternatives at length, they managed to work out a tentative agreement, and Hewer then ordered the ships to come upriver. Cudgin and Suqua had convinced him that they could work things out with the viceroy, and the two sides finally agreed on prices that they could accept. Hewer was pleased that he had contracted with them because he considered these two men to be the most capable in Canton, and he thought that Cudgin was the only man who could influence the viceroy.7

Despite the heavy extractions, 1726 must have been a very good year for Cudgin as he managed to contract over 85 percent of the business of the three GIC ships (explained below). The total value of his trade listed in the GIC account books comes to over one million taels (see Table A). This was an amazing volume of merchandise as the East India Companies rarely gave the Hong merchants more than 20 to 50 percent of a ship's cargo, so anything above 50 percent was exceptional. Besides the GIC trade, Cudgin is certain to have done business with other foreigners as well. It is thus not surprising to learn that Cudgin was one of the wealthiest merchants in Canton at the time.8

After the 1726 season, Cudgin took time off to go to Beijing with the foyen.9 In June 1727 the English mention that Cudgin was absent and that he would not be trading that year. The foyen or viceroys’ appointments were for only one to three years, and they usually started and ended their office in conjunction with the trading seasons. It was typical for them to leave office during the off-season (February to July) when there were few or no ships in Canton. This was when the next officer usually arrived as well.10

When Cudgin returned in 1728, the English mention that because he “does not appear in business”, he “has severall Relations to officiate for him”. Cudgin was now also “a mandarin”. This new title was apparently purchased from the emperor in Beijing, which was a way for the merchants to hedge against hard times. The degree could be forfeited as payment or punishment for anything that went wrong in the trade. A degree, of course, was also a way to improve social standing, and it gave them status among the government officials as well.11

One of Cudgin's “Relations” who officiated for him was Leunqua (Ye Longguan ��葉隆官 ), who begins to appear in the records in 1728. Cheong says Leunqua took over Cudgin's business in this year, which seems likely because Cudgin's trade drops off to almost nothing from this time forward. The next year, another relative, Giqua (Ye Yiguan 葉��義官 ), begins to show up in the records. In 1732 one reference states that Cudgin and Leunqua were cousins, but because Cudgin's name was also spelled “Cousin”, it is not clear whether this is a mistake in nomenclature or whether it should be taken literally.12

When Cudgin returned to Canton, we learn from the English supercargoes that he owned several of the factories. He had been leasing one of these buildings to the GIC, and he supplied the French East India Company (CFI) with a factory in 1727 as well. The EIC also approached him in 1728 to rent one of his factories, so he seems to have had extensive capital tied up in real estate. His ownership of these buildings is a sign of his affluence and status among the merchant community, but we do not know what happened to these factories when he left the trade. Leunqua and Giqua do not seem to have rented factories to the foreigners, so perhaps Cudgin sold them before he left Canton.

Cheong mentions that Cudgin retired to Quanzhou in 1732, so the trade that he conducted in 1733 was probably just to complete what he had contracted the year before (see Schedule and Table B). It is amazing that he was successful at arranging this retirement, as all positions in Canton that were connected to the trade, including pilots, compradors, linguists, and merchants, were usually appointments for life. In the early 1720s this practice was still being formalized, but by the late 1720s it had taken firm hold. Sometimes linguists or compradors would be reassigned to other posts, such as a merchant, but unless that happened, all of them could expect to serve at their jobs until they died or become incapacitated. Throughout the era of the Canton trade, voluntary resignations were not usually an option, and many of these appointments (whether they were wanted or not) came with a mandatory entrance fee.

Keeping the same persons at their posts for long periods helped to build consistency and standardization into the administration. As the operation of the trade became more regularized, it brought greater stability and predictability to profits. It also made it easier for the top officials (who came and went every three years) to manage the trade because the same persons were involved from one year to the next. This was one of the basic foundational elements upon which the trade was controlled.

The consistency helped to build the foreigners' confidence as they became accustomed to dealing with the same people year after year. With greater familiarity and the development of long-term friendships came greater trust. Those factors in turn attracted more investors and traders to China and created a steady flow of revenues to Beijing. Thus, to allay the concerns of ministers in Beijing that the foreigners should be controlled and that the funds going to Beijing would continue, there were good reasons not to allow persons to retire. For all of these reasons, merchants were rarely successful at arranging their departure, and that is why many persons, Chinese and foreign alike, considered the merchants to be nothing but slaves of the government, producing money for the latter, and expendable when they were no longer needed. This situation discouraged other capable Chinese persons from becoming merchants because there was often no way out of those positions. If a merchant was as lucky as Cudgin to arrange his freedom, there were still no guarantees that he would not be recalled when the next official arrived or when a vacancy needed to be filled.13

Considering all of the factors above, we cannot help but suspect that the 10 percent duties on silver that Cudgin supposedly paid to the foyen (or viceroy) in 1726 and Cudgin's trip to Beijing with that same official at the end of the season probably played a role in arranging his retirement. The purchasing of the mandarin's degree from the emperor (and who knows what other contributions he may have made in Beijing) may have also been part of his strategy. Getting well connected in Beijing was probably the best way to ensure that officials who were sent to Canton in the future would respect his retirement.

Whatever the case may have been, after Cudgin returned from Beijing, he immediately handed the trade over to Leunqua and began distancing himself from the commerce. He did a little trade with the Dutch and the Swedes but nothing like the volume that he had handled in previous years. It was as if he was just winding things down and waiting for the official word to arrive so that he could take his leave. This distancing of himself from the commerce suggests that if he did not have his retirement all worked out before returning to Canton, he at least had it on his immediate agenda to do so.

After he left Canton in 1732, Cudgin shows up briefly again in the English records in 1734 in Amoy, but then we hear nothing more about him after that. It is unfortunate that we do not have any memoirs or records to reconstruct the rest of his life. Cudgin was very fortunate to have been able to retire with great wealth, with other family members continuing in the trade, with a new title as a mandarin, and with apparent good health. In these regards, he was an exemplary individual and businessman who learned to work the system very well to reap the most benefits for his family, himself and his country.14

LEUNQUA

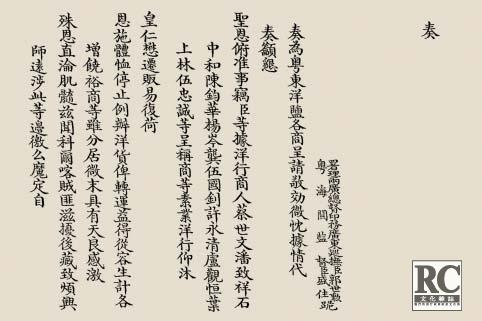

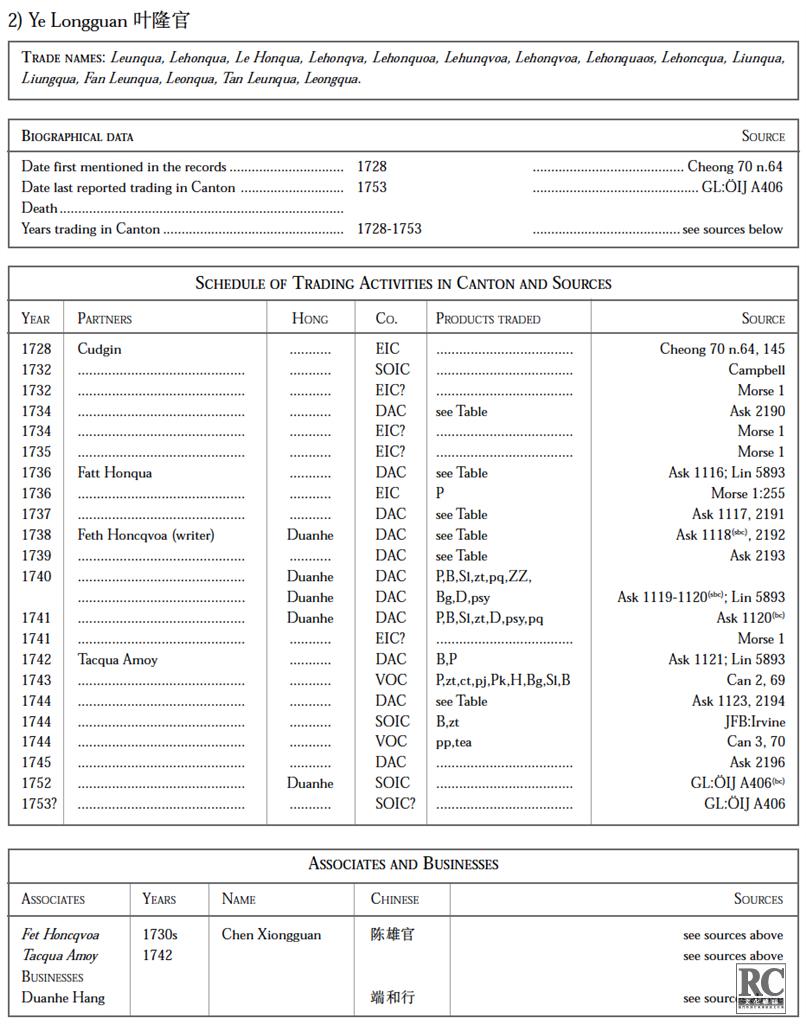

With the aid of Cudgin's experience and connections, Leunqua seems to have done well from the beginning. He shows up regularly in the records from 1728 to the mid-1740s, and the name of his business was the Duanhe Hang 端和行 (see Illustration 1).15 In the Danish Asiatic Company (DAC) records, Leunqua shows up sometimes as “Tan Leunqua” or “Fan Leunqua” (with various spellings). It is not clear why merchants sometimes appear with names like this that in no way reflect their last name. (“Ye” would be “Yip” in Cantonese, which is not close to “Tan” or “Fan” even in the wildest stretch of the imagination). These types of entries, however, are common in the records, and perhaps are due to the foreigners just not being familiar with the pronunciation of Chinese last names.

In everyday business they would usually use first names, so there is some logic to this reasoning. We know from contracts that Leunqua signed that these names are indeed referring to him, despite the way they are spelled.16

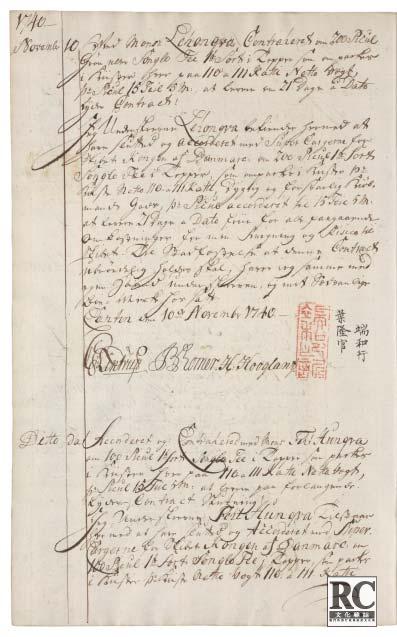

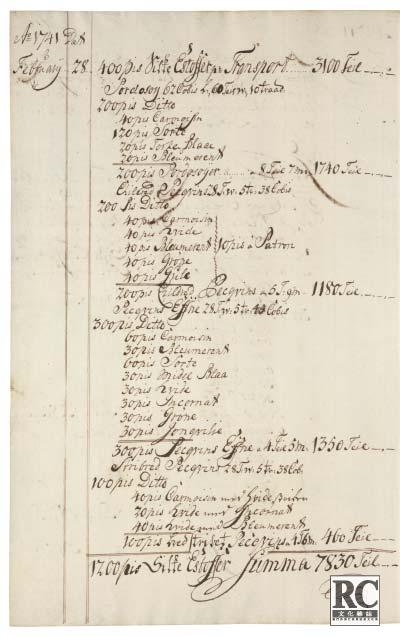

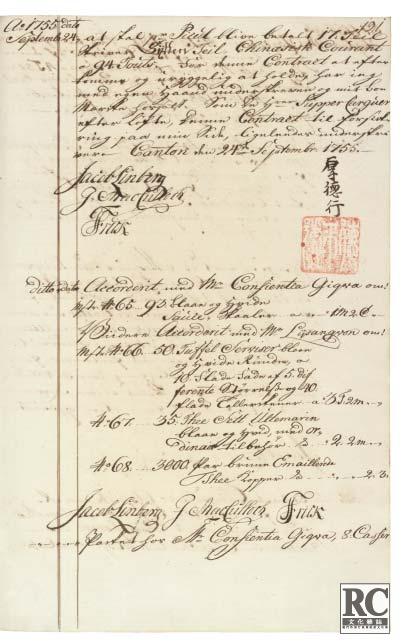

IIlustration 1: Two Tea Contracts, both dated 10 November 1740 for the DAC Ship Kongen af Danmarc. The first contract is with Lehonqva of the Duanhe Hang to deliver 200 piculs of 1st grade Songlo tea, and the second contract is with Fet Honqua of the Yuanlai Hang to deliver 100 piculs of 1st grade Songlo tea. (RAC: Ask 1120)

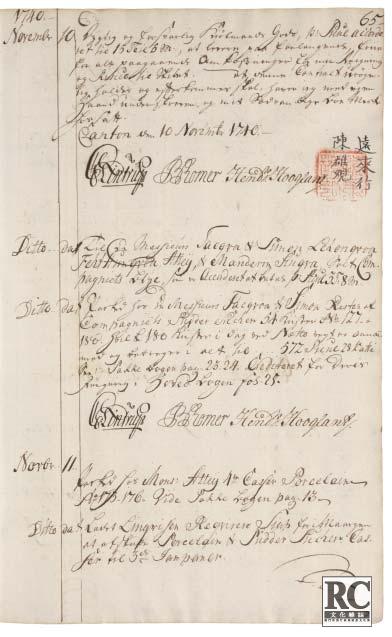

On one of Leunqua's silk contracts that he made with the DAC there is a curious chop that may shed some light on Leunqua's proper Chinese name. On the right side of the chop are the characters Ye yin�� 葉印, which simply mean this is a Ye chop. On the left side of the chop, however, are two characters that appear to be Ting Zi 莛梓 (or something close). These two words do not normally appear on business chops from the Hong merchants, so they could possibly refer to Leunqua's given name (see Illustration 2).

Illustration 2: Silk Contract dated 28 February 1741 between Lehonqva and the DAC for the Ship Dronningen af Danmarc. (RAC: Ask 1120)

By 1734 Leunqua was supplying silk to the DAC, which he continued to do in later years. In 1735 Leunqua contracted one-fourth of the EIC's silk fabrics, and the English supercargoes pressured him to take a share of their lead and woollens. By 1736 he had expanded to the point that the English listed him as one of the four principal merchants in Canton with whom they traded. Leunqua continued to do an extensive business with the Danes as well (see Table C).

In the 1730s Leunqua had a writer by the name of Fet Honqua (Chen Xiongguan 陳雄官), who helped him in the trade (see Schedule). Fet was a well-known figure in Canton whom many of the foreigners dealt with. Aside from assisting Leunqua, he also traded on his own out of two different firms: the Yuanlai Hang ��逺來行 and the Falai Hang 發來行. Illustration 1 shows one of Fet's contracts with the DAC that he made through the Yuanlai Hang.17

On 7 December 1738 all of the Europeans (except the French) assembled at Leunqua's house. From there they were escorted in sedan chairs to the palace of the tsing touc (governor-general) in the city. They met in a large square to attend a farewell banquet for the departing viceroy. The records do not say specifically, but it is certain that besides the two or three Canton linguists, the Hong merchants (including Leunqua and Giqua) would have attended this event as well. A tragic comedy was performed and then speeches and greetings were exchanged, wishing each other a safe and prosperous journey. Events such as this were very common in Canton, and all prominent foreign and Chinese persons were expected to attend. Observing such protocol was part of their normal responsibilities as Hong merchants.18

At the end of the 1738 season, we get another glimpse of the life behind the business of the merchants. Just before the Danish supercargoes were ready to depart and return to Europe on 9 January 1739, the partners Texia and Simon (Yan Deshe 顏德舍 ��and Huang Ximan 黃錫滿�� ) invited them to a farewell luncheon. The English and Swedish supercargoes also attended as did the merchants Pinkey (Zhang Zuguan 張族官��), Leunqua and Fet Honqua. These were the same merchants who had handled most of the DAC trade in that year.

Later that day, at around 7 o'clock in the evening, the same merchants accompanied the Danes in a mandarin's boat and escorted them to Bocca Tigris, where their ship was lying at anchor. They arrived the next morning, and upon the departure of the merchants, the Danes saluted them with the firing of nine cannons. Aside from showing the protocols of the trade, these farewell ceremonies and courtesies show that Leunqua and his partner Fet Honqua were indeed among the privileged class of merchants in Canton.19

In 1742 a “Tekqua” is mentioned in the English records as being Leunqua's partner. He was probably the same person as “Tacqua Amoy”, who is mentioned in the Danish records as his partner. This person's identity is unknown, but he shows up in the records trading porcelain and tea with Leunqua. Cheong says Leunqua disappears from the English records after this, but his name continues to show up in the Swedish, Danish or Dutch records until at least 1745 (see Schedule). He then disappears from those records as well.20

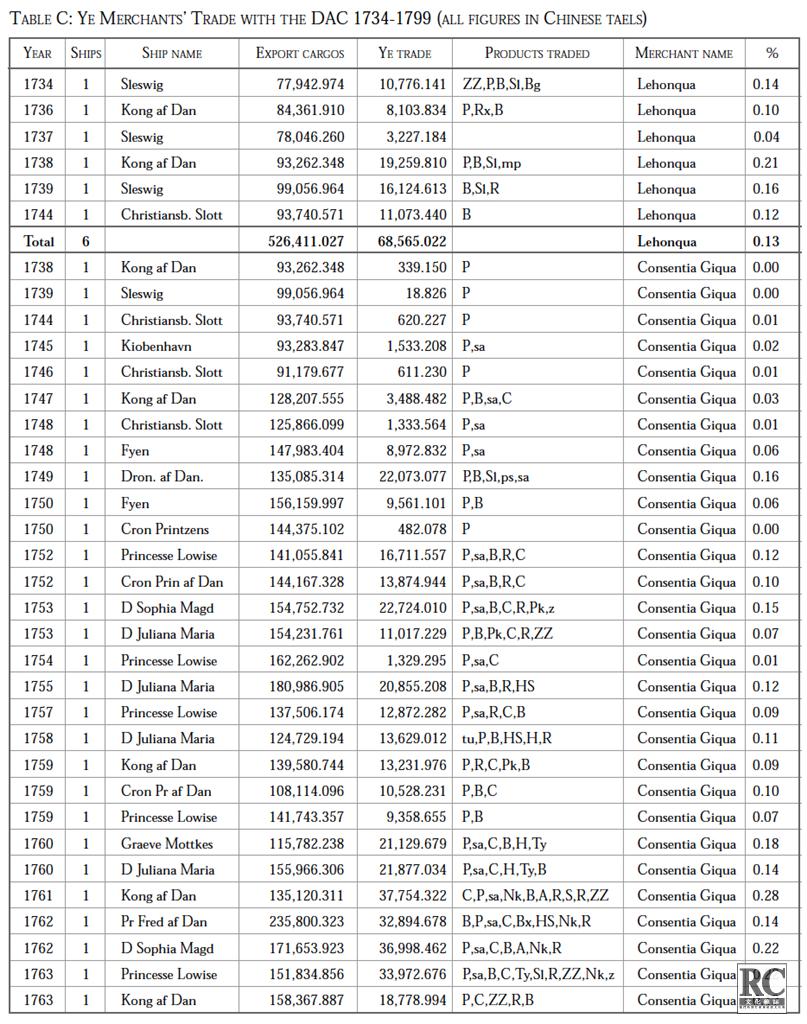

By the early 1740s Leunqua had earned a reputation for himself as one of the respectable merchants in Canton. In 1743, the Dutch list him among the six most prominent merchants (he was fourth on their list). In September of that year the Dutch East India Company (VOC) contracted many varieties of silk with Leunqua for the Japan trade because they considered him the “most capable man.” The VOC bought a large volume of products from him in both 1743 and 1744. Because we do not have account books for those years, this trade does not appear in Table B.21 Some of the Danish journals also have not survived, so the total volume of his trade listed in Table C (68,565 taels) would probably be closer to double that amount if we had all of the figures available.

Up until at least 1750, the directors of the DAC continue to mention Leunqua's name in their instructions to the supercargoes, but these documents were just copied from previous years, so the information they contain was not current. The DAC journals that have survived do not show Leunqua doing business with them after 1745. Leunqua and his Duanhe Hang appear again briefly in the Swedish East India Company (SOIC) records in 1752 and 1753, but it is not clear that he was actually trading then. One of the Swedish officers from the Ship Gothenburg, which was in Canton in 1744, owed a debt to the Duanhe Hang. In 1752 the SOIC supercargo Christian Tham paid this debt, which created a receipt that was signed and chopped by the Duanhe Hang (see Illustration 3). In 1753 the name “Leongqua” appears again in the records, but there is no reference to any trade or transactions with him.22

In 1766 and 1767 there is another “Leonqua” that shows up in the SOIC records, but there is no way of knowing if he is the same person or from a different family. Considering the long silence, it seems more likely that this is referring to someone else. As far as can be determined from the data, Leunqua of the Duanhe Hang ceased doing trade with most of the foreigners after 1745, and disappears from the records after 1753. The English mention in the early 1750s that Giqua took over Leunqua's business, so perhaps Giqua continued the Duanhe Hang or merged it into his other operations. Because of the silence in the records, we unfortunately do not know what became of Leunqua or his business.23

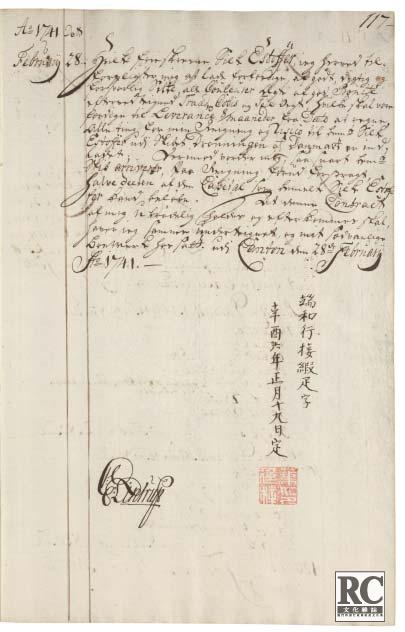

Illustration 3: Receipt for 291 Mexican dollars paid to the Duanhe Hang by SOIC Supercargo Christian Tham, on behalf of Captain Stahlhank, who incurred this debt when he was in Canton on the Ship Gothenburg in 1744. Tham recorded the date to be 6 October 1752, but the Chinese year corresponds to 3 November 1752. (GL: ÖIJ A406)

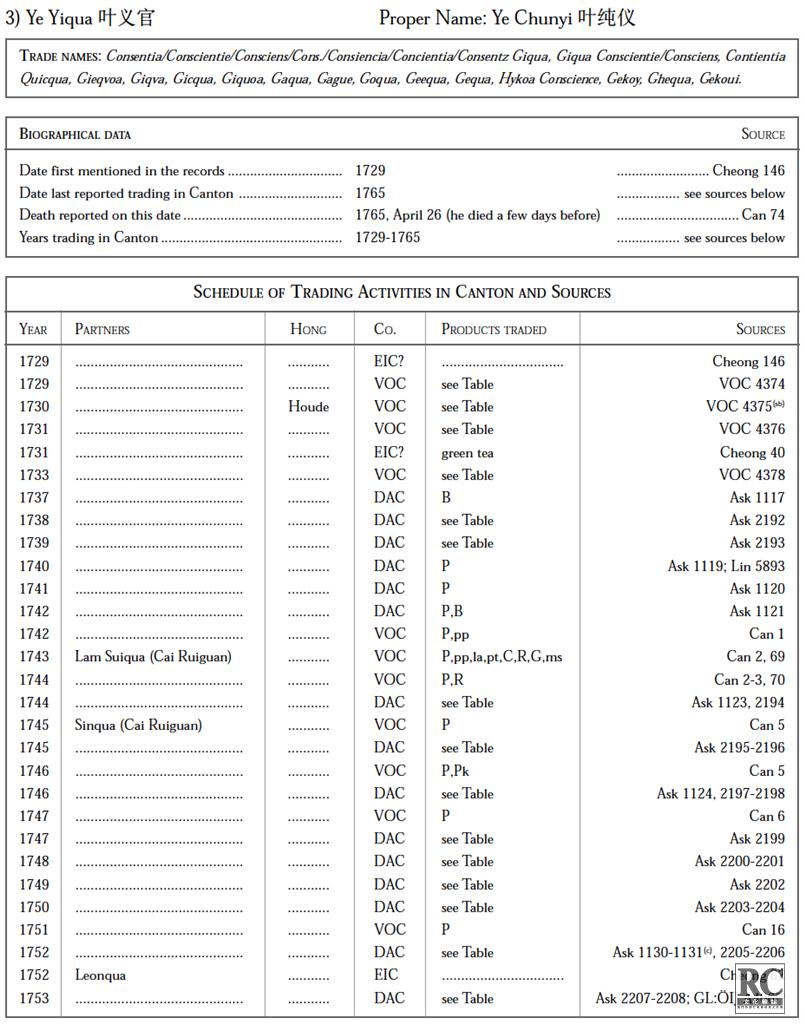

CONSENTIA GIQUA

The family relationship between Leunqua and Giqua is not clear. The two were apparently from the same family, but they rarely appear in the records working together. In the 1730s and 1740s they both traded with the DAC, but they kept separate accounts and negotiated all of their business dealings with the Danes separately (see Schedules and Table C). Giqua also traded regularly with the Dutch and Swedes in these decades but not in partnership with Leunqua (see Schedules and Table B). It is possible that the two men kept their Danish, Dutch and Swedish accounts separate and then traded with the EIC together out of the Guangyuan Hang. Cheong suggests that this may have been the case, but the information that has emerged so far is inconsistent and incomplete so the connections are unclear.24

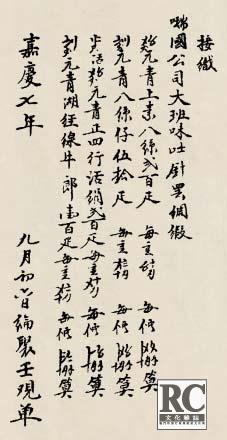

Giqua had a very unique name, which makes him easier to track through the records than some of his contemporaries. He was called Giqua Consentia or Consentia Giqua by almost everyone in Canton. Consentia is a Portuguese word meaning “conscientious” (today spelled consciência). He seems to have been very proud of this name as he often signed and sealed his contracts with a chop showing this name (see Illustration 4). Sometimes he appears simply as Giqua, and in the 1740s and 1750s there is another merchant with that name, so care must be taken not to confuse them.25

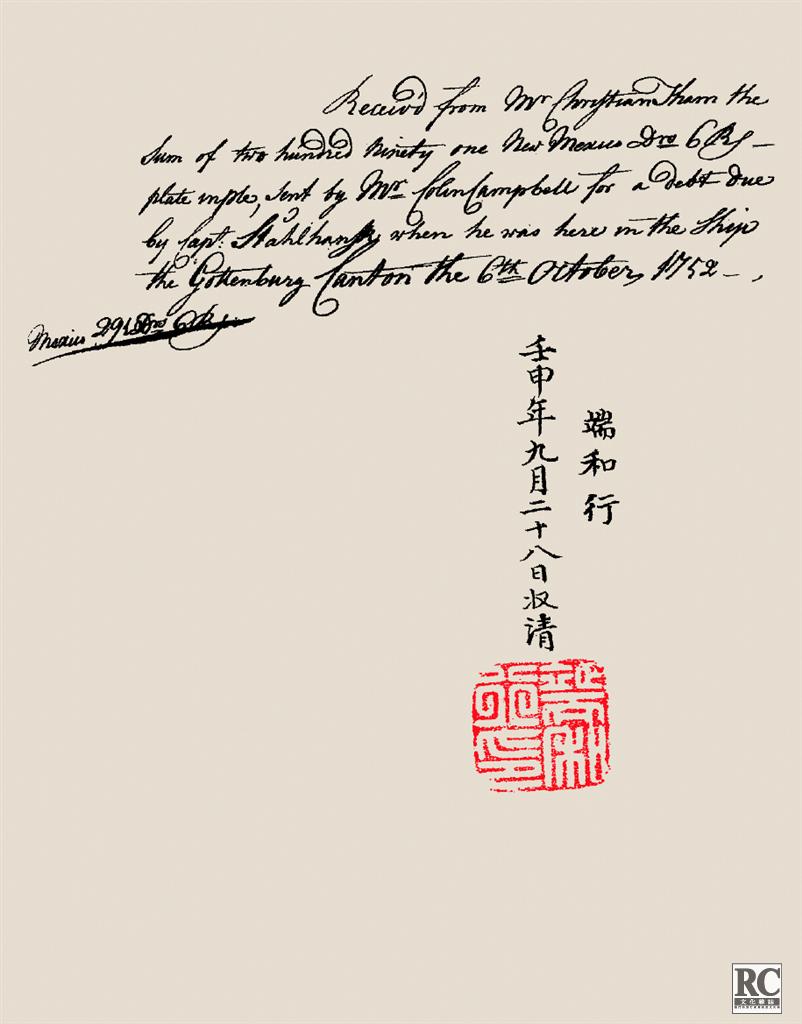

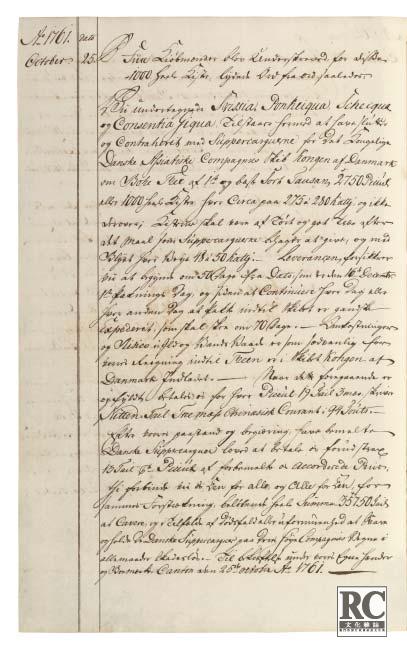

Illustration 4: Two Tea Contracts, both dated 24 September 1755 for the DAC Ship Dronning Juliana Maria. The first contract is with Consientia Giqva of the Guangyuan Hang and the second is with Avue (of the Yan family) of the Houde Hang. Both contracts are for the delivery of an amount of Bohea tea. (RAC: Ask 1135)

The first reference we have to Giqua trading in Canton is from 1729, which is one year after Leunqua began. Like most of the Hong merchants, Giqua traded in a wide variety of products, but he specialized in porcelain. Being one of the licensed porcelain dealers in Canton, Giqua had many smaller shops that exported chinaware under his authority. The normal way that this was carried out was that Giqua would receive a commission from those sales in exchange for being held responsible for paying all of the export duties and taxes. The porcelain shops of course would also have to forward the money for the duties, so as long as the shops were in good standing and paid their bills on time, this was a good way for Giqua to supplement his export trade.

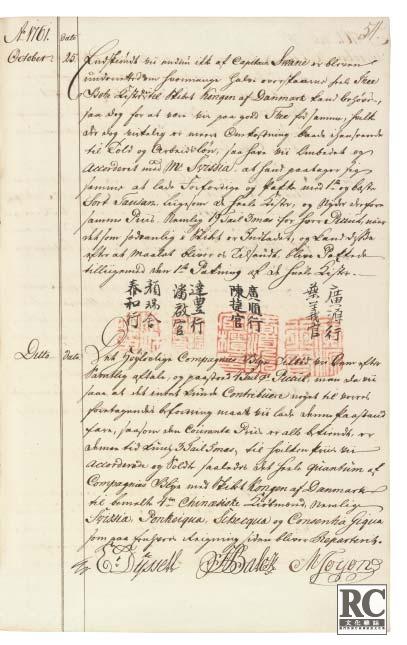

In 1730 we find Giqua trading with the VOC out of the Houde Hang 厚德行� . This business name appears again in the 1750s connected to Awue of the Yan family. Illustration 4 shows one of the contracts Awue made through this firm. We know that Awue was connected to Giqua in some of his business transactions. It is possible that Giqua sold the business to him, but Awue could have also been managing it for Giqua.26 Giqua seems to have maintained a close working relationship with the Yans. In fact, in 1761 he contracted jointly not only with the Yans, but with the Chens and Pans as well (see Illustration 5). In the 1740s Giqua also did some business in partnership with the Hong merchant Suiqua (Cai Ruiqua ��蔡瑞官, see Schedule).

llustration 5: Tea Contract dated 25 October 1761 for Bohea tea to be delivered to the DAC Ship Kongen af Danmark, with Svissia (Yan Ruishe) of the Taihe Hang, Ponkeiqua (Pan Qiquan) of the Dafeng Hang, Schecqua (Chen Jieguan) of the Guangshun Hang, and Consentia Giqua of the Guangyuan Hang. (RAC: Ask 1146)

It was common for merchants to marry sons and daughters into other merchant families and to place sons in other establishments so they could learn the trade. The commercial connections between the families created shared interests and alliances, which gave the merchants a little more security in their dealings. But the particulars that connected Awue to Giqua in the Houde Hang are not known.27

In the 1750s and 1760s, several small porcelain dealers channeled goods through Giqua's Guangyuan Hang. The names of porcelain and lacquerware shops at this time are usually easy to recognize because they often have the character chang �昌 attached to them (suggesting richness or prosperity). Some of the names of the boutiques that used Giqua's authority were Tiauquon (Yaochang 瑶徭昌��), Soychong (Juchang 聚昌��), Neyschong (Yichang 裔昌��) and Quonschong (Guangchang 廣昌��). Sometimes these names appear in the records with the character dian �店 after them, indicating that they are a small shop. One of the larger porcelain dealers, Pinqua (Yang Bingguan ��楊丙官), also sold goods through the Guangyuan Hang before he became a Hong merchant in 1782. Also, in 1763 the Dutch bought Congo-pekoe tea from Macao Taiqua, under Giqua's authority. Some of these porcelain shops continued long after the Guangyuan Hang had closed, so being outside of the Co-hong did not necessarily affect a merchant’s long-term security.28

Even though Giqua was never one of the prominent merchants in Canton, he nonetheless had a large number of people depending on him.29 Each of the porcelain boutiques had a small crew of their own, and of course there were hundreds of workers involved in the distribution and packing of tea and many other persons involved in the making of silk and other commodities. Most of this merchandise came from China's interior, so there was a massive number of people involved with communicating, ordering and shipping goods from inland to Canton.

Thus, to allay the concerns

of ministers in Beijing that the

foreigners should be controlled

and that the funds going

to Beijing would continue,

there were good reasons

not to allow persons to retire.

As can be seen from the Schedule and Tables B and C, Giqua distributed his wares to almost all of the foreigners in Canton. The charts are lacking data from the French records, and they have no information about the many private traders such as the Muslims and Armenians or the Portuguese and Spanish with whom he would have traded as well. The data are also lacking information from the thousands of records that have now disappeared from the East India companies. If we knew the full extent of his operations, we would undoubtedly have to add several pages to the tables. Considering the volume and the number of people involved, it is easy to see that keeping track of the accounting and the duties were major tasks for even the smallest of the Hong merchants. Thus, the name “small merchant” is a relative term that needs to be put into its proper context. Otherwise, we cannot fully appreciate the skill and expertise that Giqua needed to carry on his extensive commerce.

Cheong mentions that Giqua's “Hong was razed by a fire” in 1756, which presumably refers to the Guangyuan Hang. Giqua seems to have survived the immediate loss from this unfortunate event, but it is not long afterward that we see things beginning to grow worse for his business. Giqua began to lose hold of his share of the English trade, and Cheong says his position continued to weaken.30

In the early 1760s, things were not going well for any of the small merchants. After the establishment of the Co-hong in 1760, new policies were introduced that disadvantage the small merchants. The four large houses consulted with the mandarins each year to decide the terms and policies of the trade, to the benefit of themselves and to the detriment of the others. Giqua seems to have suffered considerably from this adverse situation. In February 1763, he tried to entice the Dutch to trade with him by offering them tea at the same price as other merchants but more favourable terms. They were not convinced because his tea was often poor in quality and sometimes adulterated, and he had trouble securing sufficient quantities. These factors are typical characteristics of a tea merchant in financial trouble, and Giqua was not the only one having difficulties.31

In early July 1763, the Dutch tell us that Giqua and the other five small merchants met secretly in one of the local temples to devise a means to open up the trade. After discussing the issues, they made a pact together vowing to do whatever they could to break the Co-hong, to start a second Co-hong to compete with the first, or to quit the trade all together. The reference suggests that Tjobqua (Cai Yuguan 蔡玉官��) was elected as their spokesperson to discuss the issues with the mandarins. In order to secure their commitment, all six of them drank of a sacrificial concoction made up of the blood from two pigs and two goats, mixed together with some samshew (rice wine). If nothing else, this example shows the intense animosity that had developed between the large and small merchants, with the former constantly trying to manipulate the latter.32

In 1764, the Dutch inform us that Giqua was now always pressed for cash. His business seems to have steadily declined after the fire in 1756 so that year may have been a turning point for him. The establishment of the Co-hong made a bad situation worse, but he did not have to deal with it much longer. On 26 April 1765, the Dutch, who were in Macao at the time, were informed that Giqua had died a few days earlier and left behind a large debt.

The commercial connections

between the families

created shared interests

and alliances, which gave

the merchants a little more

security in their dealings.

According to the agreement that was made when the Co-hong was established in 1760, the Hong merchants Suiqua (Cai Ruiguan), Swetia (Yan Ruishe 顏瑞舍��), Theonqua (of the Cai 蔡 �family) and Foutia (Zhang Fushe 張富舍��) were assigned to stand security for Giqua, so they were each handed a portion of his debt. Swetia died in 1763, so his brother and successor Ingsia (Yan Yingshe 顏瑛舍��) assumed his part. Because this arrangement had already been made long before Giqua's death, the Guangyuan Hang was not declared bankrupt or closed. The Co-hong appointed Giqua's son and two writers to continue the business, which they could do much more easily if they did not have the burden of making Giqua's debt payments.33

This distributing of merchants' debts to other more healthy houses of course weakened them all, but that was the idea. If they all suffered together, then all of them were supposedly on more equal terms with each other, which in theory was a way to micromanage the health of the Co-hong collective and keep them competitive. This stipulation ensured that Giqua's business would continue, which helped to keep the volume of the trade from diminishing. Aside from giving the foreigners several houses to choose from so that they could negotiate the best prices, this policy also gave them the assurance that the debts would be settled because the merchants who were in good financial standing would be making the payments. All of these factors helped to win the foreigners' trust and prevent interruptions or declines in the volume of trade. Thus, despite the obvious disadvantages to the merchants in distributing these debts, there were good reasons for doing it. One of the positive results is that Giqua's son was able to step in and take over without any interruption, which he could not have done had his father's debt stayed in the Guangyuan Hang.

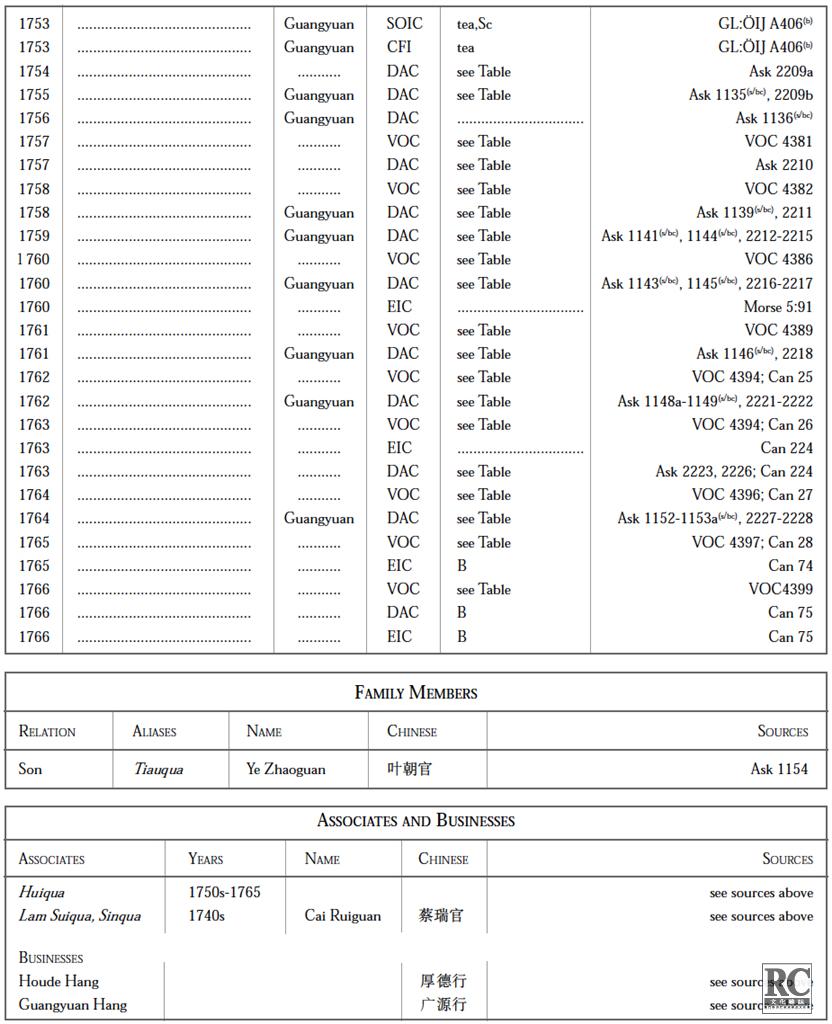

TIAUQUA AND HUIQUA

The identity of Giqua's son and successor has been a mystery surrounded by much confusion in both the secondary and primary literature. Because of the contradictions in the primary sources and the incorrect information that has been published in the secondary sources, we will take the time here to retrace the stories and resolve the issue of who exactly was Giqua's successor. The problems and contradictions come primarily from confusion in the literature about the identities of three different persons, Teowqua (also spelled Tiauqua), Coqua (or Kooqua) and Huiqua (or Hoyqua).

Cheong mentions that Giqua had “no successor” and that his firm was discontinued in 1766, but Ch'en says Giqua was succeeded by a man named Teowqua. We know that Ch'en is correct (explained below), but Cheong's argument is not without justification. In 1970, Pritchard wrote that Teowqua may have been the same person as Coqua (Chen Keguan 陳科官), who was connected to the Guangshun Hang 廣順行. Cheong also made this connection, which is why he did not recognize him as the successor of the Guangyuan Hang. Pritchard and Cheong confused Teowqua with Coqua because in 1776 the latter name replaces the former name in the EIC records, making it appear as if they might have been the same person. There is some truth to Teowqua being connected to the Guangshun Hang, but as far as we know, he did not trade out of that firm.34

Ch'en says that Giqua continued the Guangyuan Hang “until the beginning of 1768, when Teowqua (otherwise spelled Toyqua) took his place.” In another place, however, Ch'en shows Teowqua taking over Giqua's position in 1766, which is closer to Giqua's death. According to Ch'en, Teowqua continued the business until his death in 1775, and then the Guangyuan Hang was closed. Pritchard, Cheong and Ch'en all found their information in the EIC records, so there seems to be some confusion in the entries, but they are not the only sources with contradictions.35

The Dutch and Swedish records clarify a few things but also present some additional problems. As stated above, the Dutch tell us that Giqua's son, with the aid of two writers, was appointed to succeed his father. His son was closely connected to the Hong merchant families, and his experience in the trade would have made him a prime candidate to take over the business. In 1768, the Dutch say that they contracted bohea tea with Giqua's successor, and his name was Huiqua. The VOC did indeed trade with Huiqua that year and they bought tea from him, which suggests he must have been connected to the Co-hong. In 1764 and 1768, the Swedish records also show Huiqua (spelled Heyqua or Hoyqua) doing business on Consentia Giqua's behalf. From information in the Dutch and Swedish records we would thus assume that Huiqua was Giqua's son and successor, but then where does Teowqua fit in?36

Fortunately, the Danish records provide us with the answer. The following entries have been extracted and translated from the DAC journals.37

• 1765, Jul. 17: we have contracted a small amount of bohea tea with Tingva, Consentia Giqua's son.

• 1765, Aug. 3: today Tinqva asked us if we would pay him the 2,749 taels 2 mace that his deceased father Consentia Giqva had loaned to the Ship Printz Friderich last year here in Canton.

• 1765, Oct. 10: went to talk with Hoyqva, who handles Tinqva's (the son of the deceased Giqva) trade, about getting some of the rhubarb that he had on hand.

• 1765, Oct. 11: we went to Tinqva's to see the pekoe and Ziou Zioun tea, and his man Houqva boasted that they had a lot, and we found it to be of a good quality.

• 1765, Oct. 26: we have paid Tiauqua, the son of deceased Consent. Giqua, half of the amount that he was owed by the above-mentioned supercargo, dated 26 December 1764. The original principle of 2,370 taels Chinese currency, at 16 percent interest comes to 2,749 taels and 2 mace, so we paid him 1,374 taels 6 mace.

• 1766, Jul. 21: the merchants Ingsia, Schecqua, Samqua, Tiauqua (the son of the deceased Consentia Giqua) and Manqua have all served us fairly well.

• 1769, Nov. 9: we had a dispute with Hoyqua, who is from the mentioned Tiauqua, about whether he had any better tea.

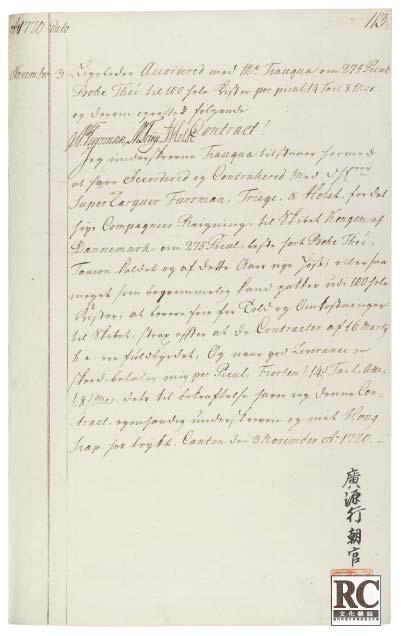

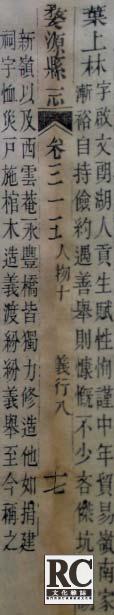

Contracts in the Danish archives clearly show that Tiauqua (also spelled Tinqva) was operating out of the Guangyuan Hang, and he signed his name: ��朝官 (Tiauqua in Cantonese, or Zhaoguan in Mandarin, see Illustration 6). No contracts have been found with his last name, but it is obvious from the references above that Tiauqua was indeed Giqua’s son. The Dutch mention that Giqua's son was married to the daughter of Chetqua, who was Coqua's older brother. Tiauqua was thus Coqua's nephew, and he was connected to the Guangshun Hang through his marriage with Coqua's niece. Thus, there is some justification for Pritchard and Cheong identifying him with that firm, but he was not the same person as Coqua nor was he a member of the Chen family. In a sense, Huiqua did indeed continue some of Giqua's business, so it is logical for him to show up in the VOC and SOIC records as Giqua's successor. Huiqua, however, was Tiauqua's chief writer, and not the inheritor of the firm. With this new information, we are now able to tell the rest of the story of the Guangyuan Hang.38

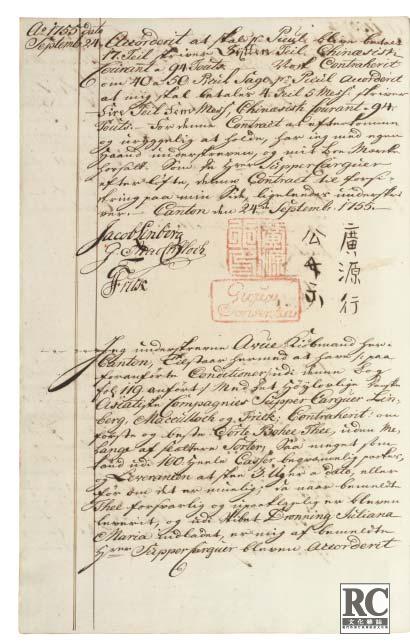

Illustration 6: Tea Contract dated 3 November 1770 to deliver Bohea tea to the DAC Ship Kongen af Danmark, with Tiauqua of the Guangyuan Hang. (RAC: Ask 1167)

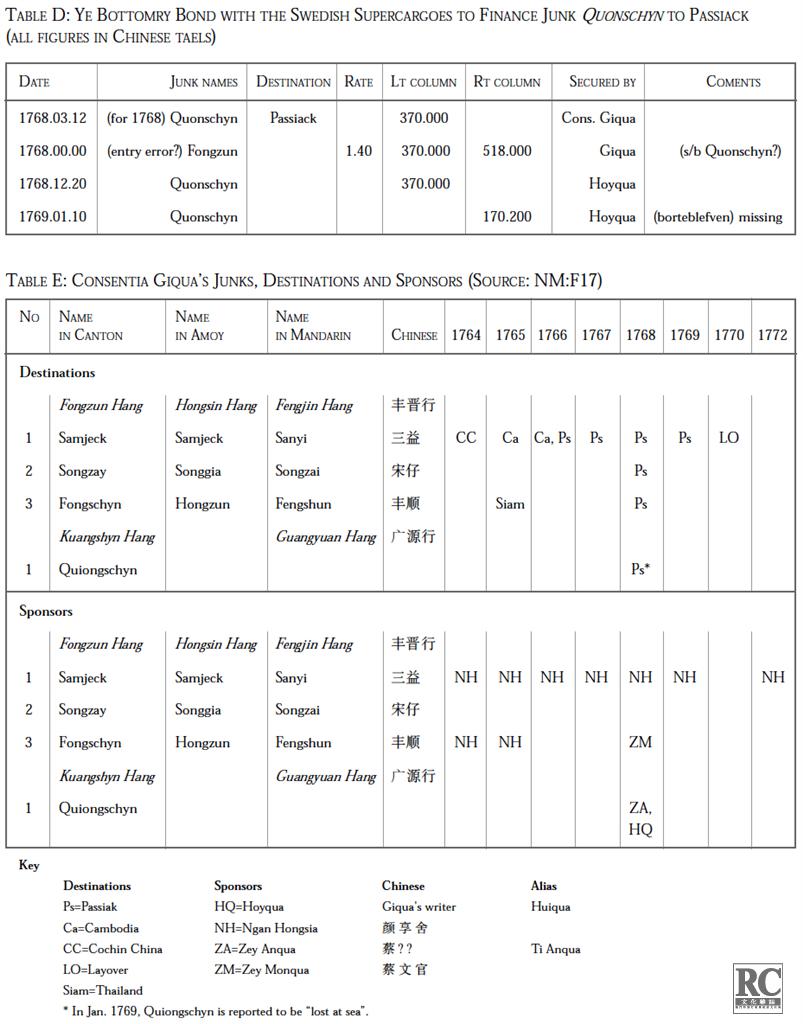

As was common with many of the Hong merchants, Consentia Giqua's name continues to show up in many of the foreign records long after his death. These entries of course are referring to his business rather than his person. Consentia Giqua is mentioned in the Swedish records in 1768 in connection with the Canton junk trade.39 In a list of twenty-eight junks that the Swedes compiled, Giqua shows up as the manager of the Fongzun Hang (Fengjin Hang 豐晉行��), which had three junks operating out of it (see Table E). Aside from these three, Giqua operated a fourth junk (see below), which seems to have been managed out of the Guangyuan Hang. These four Ye junks sailed regularly every year to Cochin China, Passiack, and Siam. They were jointly financed by Canton’s most prominent junk trader, Hongsia (Yan Xiangshe 顏享舍), but Monqua (Cai Wenguan 蔡文官) and Zey Anqua (of the Cai family) also show up in the Swedish records as sponsors of the Ye junks.

Because of the many products that the junks supplied for the export trade in Canton, it was important for the Hong merchants to be closely involved in the junk trade to Southeast Asia. Being a major supplier of porcelain, Giqua needed a regular supply of sago in which to pack the chinaware. Giqua also sold tea, which means he needed lead to line the export tea chests and tin to make tea canisters. Because the Canton junk trade went hand in hand with the foreign export trade, it was important for the Ye merchants to be closely involved with it. Huiqua also shows up connected to both the foreign export trade and the junk trade.

Huiqua handled the Guangyuan Hang's trade with the VOC after Giqua's death, but he only traded with the Dutch in two years: 1768 and 1774 (see Table B). In 1768, Consentia Giqua (probably Huiqua) took out a bottomry bond from the Swedish supercargoes in Canton to help finance the Guangyuan Hang's Junk Quonschyn, which was bound for Passiack (Cambodia, but another entry says Cochin China). In March of that year, there is an entry in the Swedish records debiting Giqua for 370 taels at 40 percent interest (see Table D).

This distributing of merchants'

debts to other more healthy

houses of course weakened them

all, but that was the idea.

As we now know was very typical in Canton, this loan actually came from several foreigners who pooled their funds together. They were all Swedish officers of the SOIC, but other cases show that it was just as likely for the lenders to include Portuguese, Armenians and various other foreigners in Canton and Macao. The total amount of Giqua's loan was 518 taels, which ordinarily would become due one or two months after the junk arrived at Canton. This would give the owner time to sell the cargo and repay the loan. The junks usually returned by September, so the repayment would be made some time in November. By the end of December, however, the Quonschyn had still not arrived, so another entry appears in the Swedish records debiting Hoyqua (Huiqua) for the 370 taels. He or Tiauqua were undoubtedly the ones who took out the loan in the first place because Giqua had now been dead for three years.40

In January 1769 news arrived that the Quonschyn had been lost, which meant the loan would not be repaid to the Swedes. Consequently, another entry appears in those records deducting 170.2 taels from Hoyqua's loan, which was the amount that the owner of the ledger (Johan Abraham Grill) lost on the transaction. The remainder was deducted from the accounts of each of the other investors. Like the Dutch and Danish records, the Swedish records also show the transactions with Hoyqua and Consentia Giqua as being one and the same.41

Tiauqua seems to have taken care of most of the business with the English and Danish companies himself. He shows up many times in those records, but Huiqua is sometimes mentioned as his partner. After Giqua's death, the EIC contracted 2,000 piculs of tea with Tiauqua's house, but under the security of Chetqua. Being Tiauqua's father-in-law, this was a logical thing for Chetqua to do in order to restore the EIC's confidence in the Guangyuan Hang. The other foreigners also contracted with Tiauqua, as they were well aware that the Co-hong had distributed his father's debts to the other merchants. In the late 1760s Tiauqua contracted regularly with the DAC and EIC, but he started running into financial difficulties in the early 1770s. In March 1771 Chetqua died, and his brother Tinqua took over the Guangshun Hang. Aside from losing the support of his father-in-law, things became considerably worse for Tiauqua at the end of this year, as it did for many of the other merchants.42

By the start of the 1772 season the Co-hong was disbanded, which led to much uncertainty in the trade. Alliances broke up, and the foreigners were wary of the new competitive environment that rapidly emerged. The fierce competition that sprang up gave the foreigners opportunities to pressure the Chinese merchants into accepting more of their imports as credit towards exports. They usually tried to make this stipulation a prerequisite to being granted loans or cash advances for the following season’s contracts as well, and they were quite successful in demanding this. On top of the already unstable environment came more distressful news in 1773, when the imperial court in Beijing requested the Canton merchants to contribute to the military campaign in Sichuan ��四川 Province, which of course they had no choice but to oblige.43

On top of all these factors were the accumulated debts that the Hong merchants were already carrying from the merchants who had failed in the past. With the closing of the Co-hong, they no longer had the ability to set prices on imports and exports or stipulate the amounts of advances and interest rates. Those controlling policies were never as successful as intended, and as is mentioned above, the small merchants did not necessarily see all of this as good for them. But after the policies ended, we can see more clearly that they did provide some security and a means to protect Hong merchants’ profits, because the risk increased immediately thereafter. One merchant after another began to fall into financial difficulties until the Hong merchant collective was in a general crisis by the end of the decade. Unfortunately, Tiauqua was adversely affected by it as well.44

In January 1772 the merchant Wayqua (Ni Hongwen 倪宏文), who was said to be connected to Giqua’s junk factory the Fengjin Hang, began to fall behind with his payments. He owed the English more than 11,000 taels, and was undoubtedly indebted to others. It is not clear how Tiauqua may have been affected by Wayqua’s problems, but it is not long after that we see him falling into trouble too.45

In 1773 Tiauqua began to fall behind on his payments to the EIC. He could not liquidate his assets before the English supercargoes went to Macao that year, and had to take out a bond to postpone the payment. He was not required to pay interest on the amount that was owed, which was a courteous thing for the English to do, but even with this favor and the additional time, he still could not settle the account when the supercargoes returned in the fall.46

Tiauqua continued to win substantial contracts with the Danes in 1773, which helped him raise the funds to pay the EIC in 1774. He was then granted a new contract with the English and more contracts with the DAC, but he was not given the opportunity to turn the business around.

According to Ch’en, Tiauqua died on 3 July 1775. It may be a mistake, but twelve days later the Danish supercargoes listed all the Hong merchants in Canton, and Tiauqua still appeared fifth on the list. This suggests that the status of the Guangyuan Hang was still uncertain at the time of the entry. The exact date when the business closed is not clear, but it seems to have been sometime in late 1775 or early 1776.

At the end of the 1775 season there were rumours circulating again of the establishment of another Cohong. These were certain to have been at least partially due to the failure of the Guangyuan Hang, which had been one of the pillars of the trade for many decades. In September 1777 the Danes describe the firm as the “failed house of Consentia Giqua or Tiauqua.” Unfortunately, Giqua’s business ended up like Leunqua’s Duanhe Hang and disappears from the records. Tiauqua's name continues to appear in the DAC records until the end of 1775. Those were transactions arranged before his death, and probably handled by Huiqua.47

When the Guangyuan Hang closed, everyone working there had to find new employment, including Huiqua, and we would expect him to show up working in a similar capacity somewhere else. In 1776 a “Hoyqua” appears in the Dutch records as Monqua's writer, which could be a reference to him. Monqua had sponsored one of the Ye junks in 1768 (and probably other years, see Table E), so the two families had some joint business dealings together and Huiqua was also involved with the junks on some level, so they would have been acquainted with each other. In the same year, Huiqua (also spelled Hoyqua, Heyqua and Hayqua) traded tea again with the DAC, but we do not know what firm he was working with.

We shall end our discussion of Huiqua with a brief mention of a very small possibility that he may have been the man who later became the Hong merchant Howqua (Lin Shimao ��林时懋). Aside from what is mentioned above, there are a number of references to a person with a name like this. Ch’en says that Howqua (Lin Shimao) traded with the English in 1768, under Monqua’s license which coincides with the Dutch references above. Cheong also shows this same Howqua trading as early as 1768, but mentions that he was Poankeequa’s (Pai Qiguan 潘启官��) writer.

The Dutch records show a Howqua acting as Poankeequa’s purser in 1772 and 1774; in 1766, a Howqua shows up in the records as Chetqua’s writer; and in 1779 and 1781 a Huiqua (again spelled several different ways) appears in the Danish records. This latter man, however, was a silk merchant with whom the Danes had dealt with in the past. Unfortunately, we cannot resolve these conflicting names and references other than to say that there appear to be several persons going by this name, and we must be careful not to confuse them with Giqua and Tiauqua’s trusted companion.48

Illustration 7: Extract from a document dated Qianlong, 57th year, 4th month, and 3rd day (23 April 1792), from the Governor-general of Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces showingYanqua (Ye Shanglin) as one of the ten Hong merchants of the Yang Hang (Shisan Hang). (Xing Yongfu 邢永福�� et al., Qing Gong Guangzhou Shisan Hang Dangan Jingxuan�� 清宮廣州十三行 檔案精选 (A Selection of Qing Imperial Documents of the Guangzhou Shisan Hang).

Guangzhou: Guangdong Jingji Chubanshe ��廣東經濟出版社, 2002, pp. 158-159 doc. no. 58).

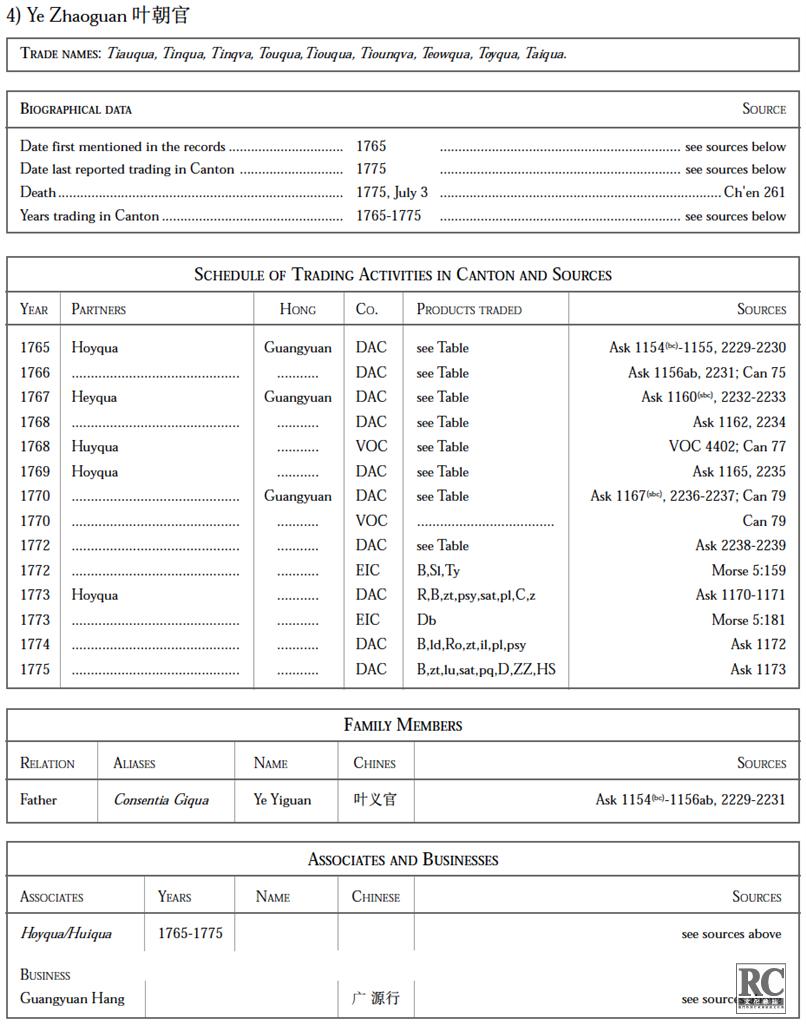

YANQUA

Close to the time of Tiauqua’s death a new Ye merchant appears in the records by the name of Yanqua. Yanqua’s proper name is Ye Shanglin 葉上林 �� , but he was more commonly known as Ye Renguan 葉仁官 (or 任官 ��). He had the same last name as Cudgin, Leunqua, Giqua and Tiauqua, and he appears in 1776 conducting some trade with the EIC. The coincidences of time and name suggest that the men may have been related. Illustration 9, however, shows that Yanqua was from Jiangsi Province and not Quanzhou like the other Ye men, so there may have been no direct family connection.49

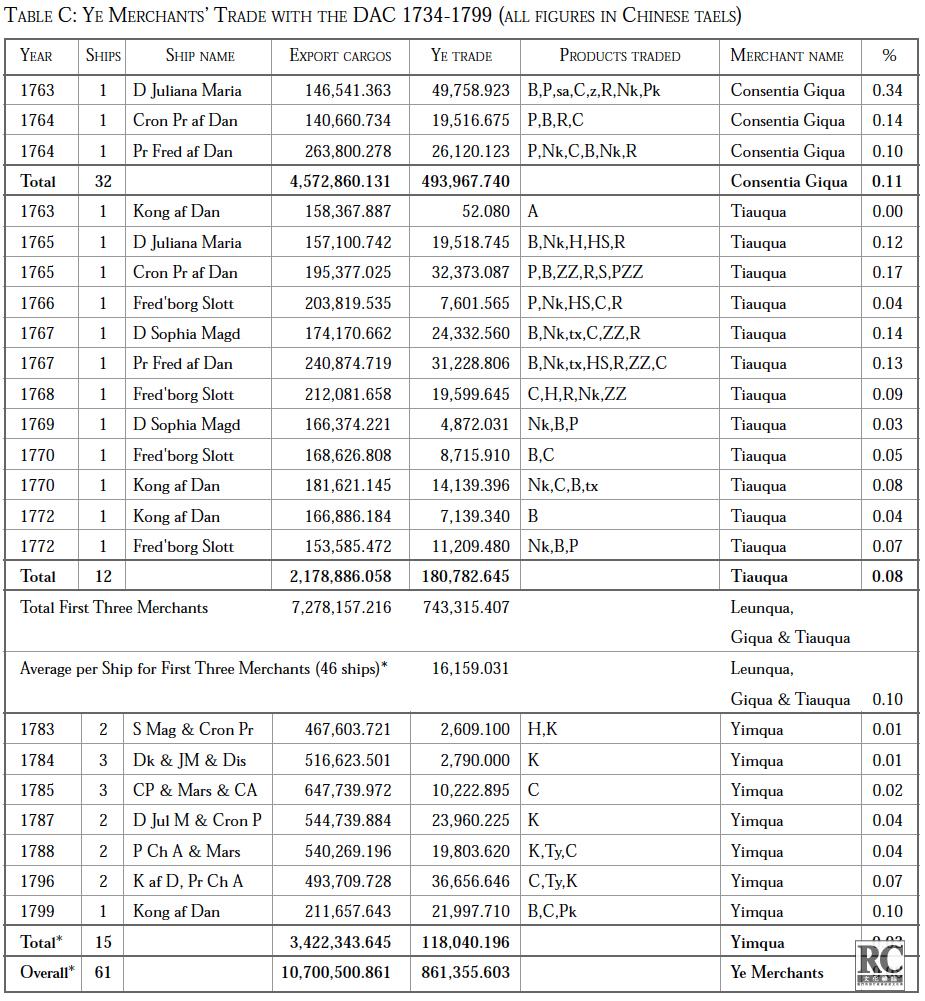

Ch’en and Cheong both mention that prior to 1792 Yanqua had been a clerk in Poankeequa’s (Pan Youdu 潘有度 ) firm, but it is not known exactly when he began that employment. By the mid-1780s Yanqua was doing regular business with both the EIC and DAC through his connections with the licensed merchants. The Danes, however, called him Yimqua rather than Yanqua (see Table C). We know that these two men are the same person because the Danes list Yimqua as one of the four Hong merchants who was newly appointed in 1792, and the other three men match up with their respective names. Illustration 7 shows an extract of a document issued by the governor-general of Canton in 1792 listing Yanqua as one of the Hong merchants that year. Before his appointment, Yanqua conducted some of his trade under the license of the Eryi Hang 而益行��, which was owned and operated by Kinqua (of the Shi �石 family). Ch'en mentions that Yanqua dealt primarily in items that could produce ready cash, and avoided taking imports for which he could not find an agreeable market, so he appears to have been rather careful and shrewd in his dealings.50

After becoming a Hong merchant, Yanqua traded out of his own firm, the Yicheng Hang 義成行��. He then enjoyed new privileges, but the new position also meant that he now had to take foreign imports in exchange for exports, which was known as “truck”. Tying imports to export sales was a very risky business to say the least, but most of the companies would not contract tea unless their imports were credited to their purchases, so now that Yanqua was a fully-fledged Hong merchant, he could no longer refuse those items as he had done in the past.51

This was a very precarious time for Yanqua to enter the Hong merchant ranks. In 1787, the Court in Beijing called upon the Canton merchants again to come to the rescue of the national budget and contribute 300,000 taels52; the Hong merchant Tsjooqua (Chen Zuguan 陳祖官��) died in early 1789 and his son Loqua (Junhua 鈞華��) was not able to pull the business together, so debts accumulated and the house failed in 1792; in 1791 Pinqua began to fall behind on his payments and was ruined by the end of the next season; in 1792 another plea came from Beijing for money to support the campaign against the Gurkhas, which put the Canton merchants behind by another 300,000 taels; by the early 1790s the long-time merchant Monqua became very discouraged and tried to commit suicide but he survived, and his business declined steadily; at about the same time the house of Yanqua's old partner Kinqua fell deep into debt, and over the course of 1793 and 1794 there was much reshuffling and redistributing of his debts; and by 1796 Monqua was bankrupt, but succeeded in taking his own life, this time putting an end to his misery.

These were hard times for the best of the merchants, but Yanqua seems to have fared better than some of the others. He did not do well in his first two seasons trading as a Hong merchant; he lost a lot on the EIC woollens that he had accepted, and became despondent about handling any more of those fabrics. Yanqua was asked to pay 50,000 taels of Kinqua's debts to the EIC, and was probably carrying some of the debts owed to other foreigners as well. He continued to trade small volumes with the Danes, and probably others, but by the mid-1790s he was looking to Poankeequa again for help in getting enough capital to order tea for the next season. Other things that were happening around him at the same time must have been very discouraging because after his appointment he soon began considering ways to withdraw from the trade.53

Fortunately, by the late 1790s things began to turn around for Yanqua. He enjoyed a high credit rating with the EIC in these years, which helped him to gain a firm foothold. One of the advantages of other merchants failing was that someone had to pick up their share, which seems to have helped Yanqua considerably. By the end of the 1797 season the Hong merchant Kiouqua (Wu Qiaoguan 伍乔官) had also failed, which gave Yanqua a boost, doubling his share of the EIC trade. He continued to increase his EIC shares over the next couple of years.

Illustration 8: Silk Contract dated October 1802 listing several kinds of silk fabrics that Yanqua sold to the SOIC (Kjellberg 156).

Illustration 8 shows that Yanqua contracted silk with the SOIC in 1802 as well. Most of the Swedish records from the late eighteenth century have not survived, so we do not know how much trade he may have done with that company. In this particular transaction, Yanqua traded the silk under the business name Lunju Hao 綸聚号�� and not Yicheng Hang ��义成行. Many of the merchants such as Giqua operated more than one business, which was a way to keep better track of different aspects of their business.

Having been very lucky to recover his losses and accumulate a small fortune as well, Yanqua proceeded more diligently with his desires to retire. Unfortunately, we do not have all the particulars relating to the negotiations that he undoubtedly undertook in 1801 and 1802. By the spring of 1803, he was ready to leave the trade, and declined contracting with the EIC. The English managed to convince him to stay on for one more season. He had already dropped his trade with the Danes, and was probably cutting all the others back as well.

Finally, in 1804 Yanqua made his move and became one of the few Hong merchants to retire from active duty. In his study on the merchants, Ch'en found Yanqua to be the only one who had been able to arrange retirement since 1760. Yanqua undoubtedly had to pay a huge sum of money to the Chinese authorities to make this happen, for which we have no details. His example, however, encouraged others like Poankeequa II to do the same. But unlike Yanqua, the emperor recalled Poankeequa back to service again.54

There are a couple of brief mentions of Yanqua in the records after he left Canton. In February 1808 there is an entry in the EIC records of Yanqua depositing 150,000 Spanish dollars into the company treasury in Canton, but the reasons for this payment are unclear. He may have been called upon to pay a debt of a failed merchant or perhaps was conducting some business. The former answer seems more logical considering that Yanqua was fairly wealthy and had no desire to continue in that profession. In 1814 Yanqua's sons were each compelled to contribute 20,000 taels to the national treasury in order to supplement shortcomings in the budget. Thus, despite Yanqua’s removal from the trade, officials did not forgot the retired man and his money.

The Wuyuan County Gazetteer, where Yanqua lived, also mentions him, but without giving a date (see Illustration 9). After retiring from the trade, he apparently returned to his native village of Langhu in Jiangsi Province where he became well known for his philanthropy. The Gazetteer mentions that Yanqua donated money to the needy, helped the less fortunate, and gave financial support to local institutions. It is unfortunate, however, that we do not have anything more specific about Yanqua’s life. Was he now happy and was he able to enjoy the fruits of his years of labour in the trade? Or did his fortune cause him more grief than pleasure?

Ch'en mentions that in 1832 the Canton authorities summoned one of Yanqua's sons to become a Hong merchant. By now, however, the family fortune seems to have diminished considerably because this son managed to evade the appointment by feigning insufficient capital to undertake the venture. He also retained his father's distain for the business, and voiced a strong disinterest in the assignment. Thus, this son’s part of the family fortune seems to have vanished, and he had no desire to return to the “glory” days of his father.55

Illustration 9: Extract from the Wuyuan County Gazetteer in Jiangsi Province, showing Ye Shanglin, from the town of Langhu, donating money to various causes. (supplied by Hu Wenzhong 胡文中).

THE YE TRADE IN SUMMARY: 1720-1804

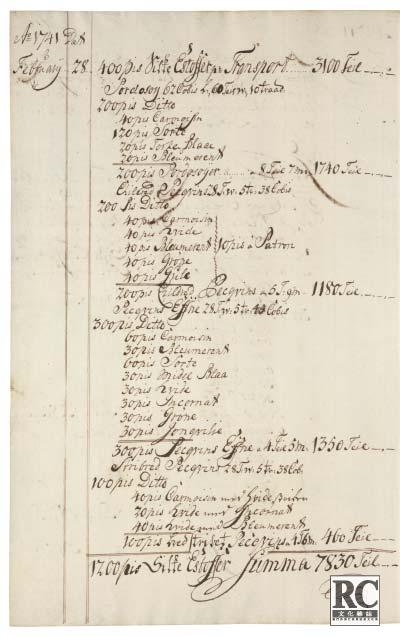

The figures in Tables A, B and C of the Ye merchants’ trade are all that we have available to reconstruct the volume of their business. We do not have good, dependable and consistent data for the GIC or VOC, so it is difficult to assemble total cargo figures for each ship, and therefore those percentages do not appear in the Tables. Table A shows the cargos Cudgin supplied to the GIC. The total figures for each ship were not available, but we were able to assemble all the merchants’ accounts listed in the books and add them together to get a rough idea of the volume. These figures are not representative of the actual trade because they often include loans that were given to merchants, advances that were made for future trade, expenses that were paid to them such as factory rents and sampan hire, and other irrelevant figures that were extraneous to the actual sales and purchases of goods.

Despite the irregularities, the totals that we were able to compile give us an idea of the extent of Cudgin’s transactions. Keeping in mind that these are just rough calculations, we estimate Cudgin's figures in Table A to represent the following percentages of the total GIC cargos each year: 29 percent in 1724; 70 percent in 1725; and 87 percent in 1726. Unlike other Ye traders, Cudgin was the security merchant for each GIC ship he supplied, which gave him the privilege of the largest share of the cargos. He clearly handled much more volume per ship than his relatives, with none of them coming remotely close to his smallest volume (the Elisabeth with 63,406 taels). In this respect Cudgin was in an entirely different class as one of the top merchants in Canton at the time.

Given the large volumes he handled and the close relationship he had developed with the GIC, it seems strange that he did no trade with them in 1730 or 1732. In 1729 the VOC ships began to arrive, and we know that Cudgin did a limited trade with them in mostly porcelain (see Table B). The volumes he supplied to the VOC were very small in comparison to those he had previously done with the GIC, to the point that they were insignificant. Thus switching to the Dutch does not explain his absence from the GIC trade in 1730 and 1732. Perhaps a more logical explanation is that he was simply waiting for permission to retire.56

Leunqua and Giqua’s entrance into the trade in 1728 and 1729, respectively, happened at a very important and opportune time in the development of Canton’s commerce. Because both of them began at about the same time, it probably made it easier for Cudgin to follow through with his desire to leave. If there had been a strong need to keep him in the trade, it is not likely he would have been given permission to retire. With the VOC ships now coming to China, a Danish ship following in 1731, and a Swedish ship in 1732, many new opportunities were opening up for trade. The two latter companies had huge vessels in comparison to the other foreigners, so in terms of volume, one of their ships equalled two of the English or French, and they were half again as large as the Dutch ships. Because all of those companies were fairly consistent at sending ships every year, some of the Hong merchants tried to attach themselves to those companies if possible so they could gain a more regular commerce each year, but Cudgin ignored all of this and continued with his desires to retire.57

As the figures in Table C reveal, Leunqua, Giqua, Tiauqua and Yanqua (Yimqua) all catered to the DAC. We do not have figures for the DAC trade from 1773 to 1781, and there are other years where the figures are missing, so the data only represent a fraction of the total number of ships that the Ye traders would have supplied. As can be seen, the average for Leunqua, Giqua and Tiauqua was about 10 percent of the total DAC volume. This was a typical amount for a small merchant to handle. Yanqua’s (Yimqua) trade is difficult to ascertain for reasons explained at the bottom of Table C, but it also amounted to no more than about 10 percent. Security merchants, on the other hand, often handled 20 percent or more. Leunqua and Giqua handled close to that amount for a few ships, but most of them were much less. The figures from at least thirty-nine DAC ships are missing from the data from 1734 to 1799, so the total trade with that company probably was about one-half to two-thirds more than what is shown in Table C.

The VOC figures in Table B are also lacking data from many years, especially 1734 to 1756. Moreover, we do not have reliable and consistent figures of each ship’s cargo as we do for the DAC, so it is difficult to allot a percentage to the Ye trade. Except for a couple of years (1758 and 1764), it was not large, with most years being no more than 2 or 3 percent of total Dutch exports. We have not found any references to Tiauqua or Yanqua trading with the VOC, so they do not appear in Table B. Huiqua appears to be the only one from the Guangyuan Hang who continued doing business with the Dutch after Giqua’s death, and that amount was not large.

Aside from the loan listed in Table D, the Ye traders do not seem to have borrowed money from the Swedes in the 1760s (the years for which we have data). This is quite remarkable considering that almost all the major merchants in Canton were borrowing both short-term (one to twelve months) and long-term (one year or more) capital from them. The absence of Giqua and Tiauqua in those transactions is itself perhaps a sign that they tried to do the best they could with what they had. If this is true, it would be consistent with their apparent lack of interest in expanding their trade any more than they already had.

Another silent area in the records is factory rents. We know that Cudgin was renting factories to the GIC, EIC and the French in the 1720s, but then when Leunqua and Giqua arrive on the scene, there is no mention of them renting buildings. Perhaps Cudgin sold the properties prior to leaving for Quanzhou. Not having factories to rent out would have hindered the other two from becoming larger players in the trade because it was common for the security merchants to provide lodgings for the foreigners. Greeting the foreigners upon arrival and offering temporary accommodations was good business, and a way to maintain good relationships with them over time. But, except for Cudgin (and possibly Yanqua), the other Ye traders do not seem to have bothered with this formality, and they also do not seem to have formed close relationships with the foreigners as other Chinese had done.

SUMMARY

The Ye traders have provided us with exceptional examples of the operations of the “small merchants” in Canton. Their trade spanned a period of about eightyfour years, which saw incredible changes in the port. In that period, the numbers of foreigners coming to China grew tenfold, from hundreds of persons to thousands. The number of ships coming every year went from about a half a dozen to more than fifty. All of this had an effect on competitiveness and the pressures on the hoppos and governor-generals to keep the trade expanding. This in turn kept the merchants in a whirlwind of changing events, with new and unexpected opportunities and burdens falling upon them at any time along the way.

The risks were high, and for some of the merchants, including Leunqua, Giqua and Tiauqua, the longer they continued in the business, the more likely it was that they would end up broke. Leunqua expanded his trade in the 1730s, but he never reached a level close to what Cudgin had done before him. As far as the records reveal, by the mid-1740s he did little or no business with the EIC, VOC, DAC or SOIC, which suggests that his businesses was in decline. Giqua and Tiauqua tried to minimize the risks to their businesses by avoiding high-interest capital and resisting the temptation of expanding and becoming major players. They also tried very hard to settle their debts as promised but were not always successful. In the end, both the Duanhe Hang and the Guangyuan Hang disappear from the trade.

Ironically, some of the small porcelain shops that channelled goods through the Guangyuan Hang lasted many years beyond Giqua and Tiauqua. Perhaps this is a sign that their business had already outgrown their strategy of keeping things small and simple. Unfortunately, once they had become Hong merchants they could not go back to becoming a small porcelain dealer. With that in mind, they seem to have employed a strategy that was effective in the short term at minimizing risks as much as possible, but then caught up with them in the long-term.

Considering the many ups and downs of the trade, it is hard to imagine that one could employ effective long-term strategies anyway because the environment was lacking long-term security for the accumulation of capital. The merchants never knew when debts would be handed to them, when local officials would come asking for a contribution, or when Beijing would send a message requesting their aid. As a result, Yanqua's sons were still being plagued with requests for money many years after their father had retired. With all of the negative factors absorbing their working capital, perhaps Giqua and Tiauqua had the right outlook all along. They played out their roles in the best and safest way that they knew how. They do not seem to have ever reached a point where they had enough money to be able to retire, or perhaps they had no wish to retire. It is a pity, however, that their stories end in financial failure because it makes their many years of devoted service seem of little importance.

Giqua probably knew long before it happened that his business was headed for ruin. Because he and Tiauqua were conservative in their dealings, they had fewer options to turn the business around once it began its downward trend. It would have been out of character for them to borrow large sums at high interest or risk taking more foreign imports in order to expand their share of the market. Taking a more aggressive approach to the situation may have helped them pull out of the trap they were in (volumes too small to produce profits sufficient to cover liabilities), but that was not an option in their personal codes of conduct or characters.

Giqua does not seem to have had the stomach for all the conniving, conspiring and compromising that the large players had to employ to push their trade forward. The Dutch mention that towards the end of his days, Giqua was wanting for ready capital, which must have been very frustrating for him. He was not one to go around begging for a contract or using high pressure tactics to woo the foreigners to his house, but rather offered the foreigners a fair deal or provided them with a loan now and then to gain their favor (such as the DAC). He was also one who wanted to honor his obligations, which left him with a dilemma: how to get enough cash to cover liabilities without compromising his beliefs.

He had adopted his name “Consentia”, which he stamped on his contracts and was a name that was consistent with his character. Perhaps the legacy that Giqua wanted to leave behind is the name itself. When all was said and done, it did not matter who won or who lost, but rather how one played the game (honestly and conscientiously). We could say the same of Tiauqua as well because their strategies seem to have been very similar. Yes, they fell on hard times and left nothing material behind for posterity, but they did not compromise their dignity, and as a result their reputations continue into the future.

Leunqua was more aggressive than Giqua and Tiauqua, but still conservative compared to Cudgin and Yanqua. All three of them were successful at gaining a market share, but only Cudgin and Yanqua were successful at rapidly gaining a market share and at keeping the profits they made from that trade. Even though their retirements are separated by a good seventy years, Cudgin and Yanqua employed similar strategies. Both of them had a couple of very good years when they greatly expanded their share of the trade; they were both very fortunate to make huge profits in a short time; and they both got out of the business as quickly as they could with those fortunes. In the beginning Yanqua appears to have been very conservative like Giqua and Tiauqua, but he eventually saw the rationale in expanding his market share when others around him were failing. Cudgin employed the additional strategy of becoming a mandarin and seeking the support of acquaintances in Beijing.

Both Cudgin and Yanqua worked for a few years more after they had begun their plans to quit the trade. This period was probably necessary in order to work out the angles and explore the options in arranging their successful retirements. They apparently covered all of the factors that might have opposed them because as far as we know they were not recalled. It is unfortunate that they did not leave behind a “how to” manual for the other merchants to follow, as Cudgin and Yanqua were indeed exceptional men among their contemporaries.

We do not know what became of Cudgin’s estate after he died. His inheritors were certain to have encountered periodic “requests” from government officials just as Yanqua’s sons had. It is hard to imagine it being any other way. Today there is a life-size image of Yanqua in the Peabody Essex Museum, which is very fortunate to have survived. Other artefacts from Yanqua's fortune and estate are now long gone. Thus in the end, maybe Giqua was right all along: it was how you played the game that really mattered.

A NOTE ABOUT THE CITATIONS

References that have a signature in Chinese characters of the name of the merchants are noted with the bracketed superscript “(s)” such as CR: Ask 2190(s). References that have the name of the business in Chinese characters are listed with a “(b)”. References that have the superscript “(s/b)” have either a signature or business name or possibly both (unfortunately, these were not clearly referenced). References that have only a chop and nothing else are noted with the superscript “(c)”. In most cases the chops show the business names but not the merchants’ personal names.

ABBREVIATIONS FOR SOURCES AND ARCHIVES

Ask Danish Asiatic Company Archive in the National Archives, Copenhagen.

Campbell Paul Hallberg and Christian Koninckx, eds. A Passage to China, by Colin Campbell, Gothenburg: Royal Society of Arts and Sciences, 1996. This source has an index in

the back, so the page numbers for various entries of the persons can be found there.

Can Canton Archive in the National Archives, The Hague. 1.04.20 Ch'en Ch'en Kuo-tung, Anthony. The Insolvency of the Chinese Hong Merchants, 1760-1843. 2 vols. Taipei:

Academia Sinica, 1990.

Cheong Cheong, Weng Eang. The Hong Merchants of Canton. Copenhagen: NIAS-Curzon Press, 1997.

G/12/1-292 Oriental and India Office in the British Library, London. The G/12 series are the EIC Canton Factory Records.

GL Gothenburg, Landsarkivet [Provincial Archive]. Öijareds säteris arkiv A 406. Seriesignum F III. This source is cited as ÖIJ A406 in this paper.

IC Ostend General India Company Collection in the Stadsarchief [Municipal Archive], Antwerp.

Irvine Charles Irvine Archive at the James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota.

JFB James Ford Bell Library, University of Minnesota. The B 1758 fNe collection contains VOC records from Canton in 1758 and the Charles Irvine Collection contains SOIC

Canton records from the 1730s and 1740s with some information from the 1720s as well.

Liang Liang Jiabin粱嘉彬. Guangzhou Shisan Hangkao ��廣州十三行考 [Study of the Thirteen Hongs of Canton], 1937. Reprint, Taipei: 1960; Guangdong 廣東: Renmin Chuban

She 人民出版社, 1999.

Lin Lintrup family archive number 5893 in the Rigsarkivet [National Archives], Copenhagen.

Morse Morse, Hosea Ballou. The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 1635-1834. 5 vols, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926. Reprint, Taipei:

Ch'eng-wen Publishing Co., 1966. Numbers such as 1:266 refer to vol. 1, page 266. If only the volume number is given, then the pages can be found in the indexes at the

back of volumes 4 and 5.

NAH National Archives, The Hague.

NM Nordic Museum Archive, Stockholm. Godegårdsarkivet Archive F17.

OIO Oriental and India Office in the British Library, London. The G/12 series are the EIC Canton Diaries.

PMA Antwerp: Plantin-Maretus Museum (PMA). Number 479 contains a copy of the Grootboek and Packboek for the ships GIC Arent and Elisabeth in 1724.

RAC Rigsarkivet [National Archives], Copenhagen SAA Stadsarchief [Municipal Archive], Antwerp.

VOC Dutch East India Company Archive in the National Archives, The Hague. 1.04.02.

OTHER ABBREVIATIONS

A amber

An Ankay tea

B Bohea tea

Bg Bing tea

C Congo tea

Can short for “Canton”

CFI French East India Company (Compagnie Française des Indes)

ctn cotton

D Damasks

DAC Danish Asiatic Company (Danske Asiatisk Compagnie)

Db debt

E Enquay (Ankay) tea

EIC English East India Company

F Fiador (Security Merchant)

FR Factory Rent

G gold

ga galingale

GIC Ostend General India Company

gn gorgoran (fabric)

Gt green tea

H Hyson tea

HS Hyson Skin tea

il illustering (fabric)

K Kampoy tea

Kz Keizer tea

la lakenen (worsted fabric)

ld lead

ln linen

LO layover

lu illustering (fabric)

mp mother of pearl

ms muscus (musk)

Nk Nankins

Nl Nanking linen

P Porcelain

Pk Peko tea

pj putchuk

pl pelangs (fabric)

pp pepper

pq Pekings (fabric)

ps powder sugar

psy pordesoys (fabric)

pt perpetts (fabric)

PZZ Patri Ziou Zioun tea

Q quicksilver (mercury)

R rhubarb

Ro rottinger (rattan or cane)

Rx radix china

S Soulong tea

sa sago

sat satin

sau saulane

Sc Souchon tea