Praia Grande, seen from the Northeast. Watercolour. Private collection.

Praia Grande, seen from the Northeast. Watercolour. Private collection.

If he had lived 100 years later, George Chinnery might have been remembered as an international fugitive instead of a respectable British artist experiencing hard times.

In 1825 when he landed in Macao, he could step ashore fairly confident that his reputation was intact.

There would be no policemen waiting with warrants for his arrest. No one knew him other than those who had lived in or had connections with Calcutta or Madras where he was active for a period of 23 years before taking ship to Macao.

He had begun his artistic career as a teenage pupil of the great English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds, and had risen - in his own estimation at least - to be one of the five top British portraitists. Seeking new inspirations he had moved to India in the early years of the 19th century where he had family connections in business.

In the course of his stay in India he had made his name as a well-known and well-patronised painter of the Indian establishment.

But after a hectic social life this bon viveur had left the country owing large sums of money, not to mention uncompleted assignments and a tattered reputation.

Essentially Chinnery was a fugitive, if not from justice, then certainly from creditors and his social peers.

The local press in Calcutta, then headquarters of the East India Company, were kind enough not to mention this faint whiff of scandal, assuring their readers that he had left the country for the good of his health and on a working holiday to sketch and paint new scenes.

But it did drop the hint that "we hope circumstances will admit of his returning" - almost in the same way that Police mention that they would like to interview certain people who might be able to help them with their inquiries.

Not if Chinnery could help it, however. Not only did he have large debts to settle, but he had left his much maligned wife behind in Calcutta, and the artist wished to put as much distance between them as possible.

It was as much to escape from her and his family tragedies - the death of his son and heir and the disclosure of two illegitimate Anglo-Indian sons -that he had fled the country.

Chinnery was at that stage of his life suffering severe depression. But in taking himself to the Portuguese territory of Macao, he was effectively removing himself from the long arm of British justice.

S. Paulo Church, before the fire, 1834. Pencil and sepia on paper.

S. Paulo Church, before the fire, 1834. Pencil and sepia on paper.

While the East India Company maintained premises in Macao the writ of British law held no sway or influence. Portugal might have been Britain's oldest ally but where colonial expansion, commerce and trade were involved it was a case of every man for himself. If his creditors wanted him, they would have to come and get him.

In 1825, there was no colony of Hong Kong and the nearest British presence was far to the south in the island of Singapore which Sir Stamford Raffles had bought from the Sultan of Johore for the East India Company six and a half years earlier.

Portugal at that stage could claim a presence in Macao dating back almost 300 years and in that time the small peninsula - no greater than two square miles - had built up, if not a thriving community, certainly an established trading infrastructure.

It had developed a silk and silver trade with the Japanese in earlier years and dealt in spices with East Timor, Goa and Malacca. Its caravels and sailing ships sailed east to Manila in search of cotton, cobalt, tobacco and wax.

Its wealthy had built mansions on a palatial scale. A variety of churches, supported by Jesuits, Dominicans, Augustinians and Franciscans, occupied prominent places in the city which grew up between Penha Hill in the south and the Monte Fort in the north leaving a rural buffer between it and the Barrier Gate.

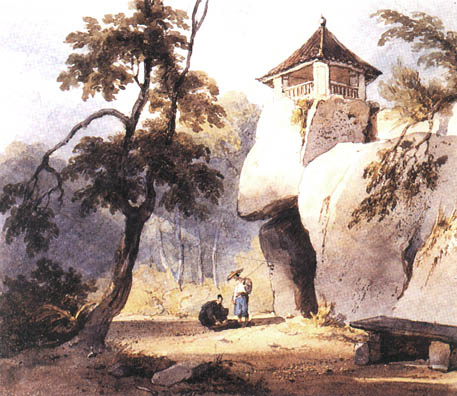

Camões Cave, about 1883-38. Watercolour on paper (not dated).

Camões Cave, about 1883-38. Watercolour on paper (not dated).

Later years would see the Governor's residence rise majestically to the south of Penha Church. First built in 1622 as a thanksgiving by passengers and crew of a Portuguese ship which had escaped the clutches of the dreaded Dutchmen, the Penha Church became a shrine to Our Lady, the protectress of mariners and all who sailed on the pirate-infested China seas.

Macao in those days had a name which fully reflected Portugal's pride and greatness - "City of the name of God, Macao. There is none more loyal"- a testimony to its fidelity when it continued to fly the blue and white Portuguese flag during the brief 60 year Spanish interregnum in Europe.

Before that it was merely "Port of the name of God in China."

Its elevation saw not only the erection of a cathedral and more fine churches, but a flowering of the missionary spirit implanted by the first Portuguese settlers.

For while rough and tough traders, seamen and soldiers manned the first caravels to poke their bows into the muddy brown waters of the Pearl River estuary, men of God were there as well.

The greatly revered and saintly Spaniard, Francis Xavier had led the quest to establish a presence on the mainland of China. Having reached Kagoshima and raised the Cross in Japan, he set foot on the Chinese island of Sancian, there to meet his death - never quite on the mainland of China but certainly within sight of his goal where later missionaries would take the gospel.

For the church was as influential in the growth of Macao as traders, businessmen and officials. Often there were more priests and monks than soldiers, and it was priests who sometimes led the fight against would-be invaders. Who could forget the doughty defence of the city by the guns of Monte Fort in 1622 and Fr. Jeronimo Rho's lucky (or inspired) shot which struck the Dutch ammunition ship? But for that, another flag might have been raised above the city.

Steps at the S. Francisco Church, about 1835-38. Pencil on paper (not dated).

Steps at the S. Francisco Church, about 1835-38. Pencil on paper (not dated).

When Chinnery arrived on September 29, 1825, it was a city steeped in legend and history. Though it had seen better days, its forts, churches, houses, terraces, barracks, temples and cobblestone streets oozed history, like the ubiquitous roots of the banyan tree; they were living artefacts preserved in a time warp of the earliest years of Portuguese colonialism.

The architecture of the 16th and early 17th century, first raised in Goa, Mozambique, Malacca and Timor, migrated to Macao. The Romanesque churches of southern Europe were transplanted not just to south and central America but to the Far East.

Chinnery must have soon realized that here was a community even more intriguing than the patchwork of states that made up India with its contrasts of princely opulence and beggarly decay.

While his first need was to secure a roof over his head he was acutely aware that the one commodity he sorely lacked was money. He would have found quickly that patacas did not grow on trees and that promises meant nothing to the hard-nosed traders who kept seasonal homes in Macao. Nor were there easy loans for impecunious artists. He would have to demonstrate ability and reliability.

Arriving in September, Chinnery would have noticed that most of his potential clients had slipped off to the so-called factories on the Canton river front to do business for the winter season. He would have to follow them to make their acquaintance and to offer his services.

Fortunately his contacts from India gave him an entree to a few of the big tea and opium merchants and for the next few months he found lodgings and support in return for his sketches and paintings.

But back in Macao - and one of his earliest sketches bears the date of December 10, 1825 -the pickings were leaner. Happily Chinnery was not an indolent man and daily he would venture out from his lodgings, at one time, No 8 Rua Ignácio Baptista, find a shady spot and sketch whatever passed by.

These hundreds of drawings became the basis for sketchbooks popular as much with the Canton merchants as with many visitors who flocked through Macao. One of his first was compiled two months after his arrival in 1825 and features on its cover the facade of St Domingos church.

The Inner Port, viewed from the Garden House. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

The Inner Port, viewed from the Garden House. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

During the next 27 years, weather and health permitting, Chinnery made it a rule to spend part of the day on the streets, sketchbook in hand, to draw whatever came to view.

In the course of years he assembled a collection that has left us a remarkably detailed picture of the buildings, churches, forts, people, trades and occupations.

Curiously, however, there are few if any surviving portraits of Portuguese officials or of their wives and families. Of British, American and foreign traders there are many. There are also excellent paintings of the main Chinese Hong merchants. They would have sat for him, in their magnificent official mandarin gowns. One, of Howqua, was submitted to a major London exhibition, drawing much favourable comment.

In another ink drawing, Chinnery sketched two veiled women passing by a church, possibly St Domingos, with a servant carrying a large umbrella to protect them from sun and rain. Another shows what appears to be a procession of clergy in billowing copes, climbing the steps to St Paul's.

These he doubtless embellished and completed in his Macao studios on the many days in the year when rain and wind made it impossible to venture out of doors.

But because of the cost of canvas and paint and the occasional difficulties in ordering fresh supplies, Chinnery committed far more of his impressions to paper using pencil and ink.

There are literally thousands of his drawings surviving to this day. Frequently he sketched several scenes on the same sheet of paper. These he never or rarely threw away but as an ardent collector of trash and trivia, placed in large trunks in his bedroom - how well documented can only be guessed.

Many are to be found in collections in London, Lisbon, Tokyo and Hong Kong. For while his rough sketches had no value other than as a guide to the artist's finished drawings, today mere pencil strokes fetch hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars in sales and auctions.

Seldom are they signed or dated, rarely inked in, even more rarely do they carry a wash or tint. But the Chinnery hand is unmistakeable and though he coached pupils, including Macao's famous artistic son, Marciano Baptista, and encouraged many to draw, none was able to emulate his style.

Highly prized as sketches of a bygone era, it would be difficult today to assemble even a streetscape because they are so scattered.

But scenes of churches such as St. Lawrence's, St. Joseph's seminary, St. Augustine's, even the ruins of St. Paul's exist in practically every major collection One particularly beautiful watercolour in the Toyo Bunko collection (formerly owned by G. E. Morrison in Beijing) shows the portal to St. Joseph's seminary, with its shelled cupola surrounded by a stylised vault.

In the same collection is a watercolour of Camões Grotto, its huge rocks surmounted by a Chinese pavilion, in a secluded, leafy setting.

The fortress of St. Paul, the Holy House of Mercy (Santa Casa da Misericórdia), the Bomparto Fort (later to become the Bela Vista Hotel), Santiago Fort, the temple of A Ma, the praia and beachfront of the outer harbour were subjects which drew Chinnery back time and time again.

One of his first sketches was of the "Bishop's Citadel and Franciscan Fort," probably sketched in the vicinity of what in later years was known as Jardim S. Francisco, with the Monte Fort in the background.

He painted and sketched the St. Francisco monastery and church from many vantage points, one particularly striking ink drawing from a beach on a day so calm that the waves hardly rippled.

More often than not, Chinnery avoided climbing difficult hills and is prepared to give us the worm's eye rather than the bird's eye view of a fort or church. However, some of his most striking views of the city are those sketched from a height.

Ionian, Doric and Corinthian columns stand sentry outside grand official buildings, many with wide, granite stairways leading to the office of higher authorities, poring over documents high above the mere minions who shuffle along the cobbled street below.

In the collection of the Geographical Society of Lisbon is a sketch of the old East India Company headquarters, drawn in the summer of 1832, on the Praia Grande, and six years later a rough sketch of the old Barrier Gate, with its collection of dai pai dong for the weary traveller seeking a bowl of noodles and a pot of tea as he entered the city.

Coupled with the legendary landmarks and magnificent mansions were the humble homes of ordinary people. He must have known every roof tile and brick, every plaster facing, the distinct design of each window of each house, the long dark shutters, closed against typhoon winds and the baking summer sun, the retractable wooden sun shades over each doorway.

A curious fact, however is that Chinnery rarely ventured inside - who knows, he may have been warned off; not even the nave and sanctuary of a church is to be found. The one exception was when he set up his sketchbook within the ruins of St. Paul's shortly after the 1835 fire.

He was primarily an outdoors' artist and together with his sketches he left shorthand notes on colour, shading and sometimes self-criticism - "not quite right" was a note he left next to the hand of a calligraphist.

As an outdoors' artist he was certainly a well-known personality. Chinese residents obviously ignored him - in spite of the taboo against being sketched - and his illustrations include people from many walks of life.

Likewise, he made many excellent and detailed sketches of Chinese temples, including A Ma Temple on the south-western shore. But strangely there were few recognizably Portuguese people, and rarely soldiers, in his drawings. The national flag, however, features prominently.

A-Ma temple. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Chinnery at times would hire a sampan and sketch the beautiful Macao bay, with the Praia Grande in the background, lined with colonial buildings. These were so popular that he often used water colours and oils to capture this magnificent scene, alas lost to the present generation with the reclamation of the bay. So prolific an artist was he that, with access to all his work, it would be possible to make a composite of large parts of urban Macao in the early 19th century. And from those that are dated it would be possible to follow his daily meanderings. In later years, because of his growing bulk, he resorted to a wheeled chair, pushed by a servant.

Revisiting the past through pictures is common enough but rarely has one community been so thoroughly and systematically recorded and documented as Macao by its 19th century artists.

Regrettably Chinnery had none of the courage of the young French artist and traveller, Auguste Borget, who in 1839 took pencil and notebook into the nearby camp of Chinese soldiers to sketch them at training and manoeuvres.

For when danger threatened, Chinnery put personal safety first. In one of his letters he spoke of "passing a night of horror and presentiment" being "in the greatest misery" fearing that he "would be put to the sword."

This was during the dark days of 1840 when Anglo-Chinese tensions were rising and the Portuguese were clearly unhappy about a continued British presence in their city.

A year earlier, Commissioner Lin Zexu had marched his troops through the streets of Macao in a show of force. Little wonder Chinnery locked himself inside his room - though it would have been a spectacular scene to sketch or paint, if only for posterity's sake.

Surely even Chinnery must have risked a squint through half-opened shutters. Perhaps he did, for there is one delightful sketch of a "Mandarin with train" in the Lisbon collection which is unfortunately undated. This procession, led by gong-beating and flag-flying escorts, shows an armed guard leading two sedan chairs. It is full of movement and one can almost hear the tramp of their feet. This is a ground-level view with no indication of locality. A flight of steps nearby, under a large tree, suggests the A Ma temple.

In his parade, Lin, magnificently attired, was carried in a sedan chair by eight porters, led by an officer on horseback, and with a troop of men beating gongs and holding fluttering banners.

By that time, most of the British community had embarked for Hong Kong where they spent an uncomfortable summer living on ships while seamen went ashore to buy fresh vegetables, meat and fish.

Chinnery's few pictures from this era suggest he did not join the refugees - shipboard life being another of his hates.

He did make a visit in 1845, apparently at the invitation of one of his wealthy patrons, to sketch the new colony then rising from the shores of Hong Kong island.

But his stay was restricted to a few months. The summer heat and humidity did not agree with him; the mosquitoes made life miserable and he was pleased to return to the civilisation of Macao, even if it meant slipping incognito past a customs officer as he disembarked from a junk.

He went back to sketching, but after the foundation of Hong Kong, his patrons were fewer. The traders and merchants who used to spend their summers in Macao never returned. A new concession known as Shameen grew up on the banks of the Pearl River outside the battered walls of Canton.

Soon magnificent new residences would occupy this area, and these would not be sketched by artists like Chinnery, Borget, Baptista, Warner Vanham and Lamqua, but captured in photographs. For Chinnery's death in 1852 was followed swiftly by the age of the camera. This new process, marked in its early years by stiff, formal figures standing rigidly by aspidistras, and later sweeping external panoramas, would rapidly replace the small group of artists and painters who made their living by paint and pencil.

The Chinese "handsome face painters" of old Canton, gave way to photographic studios, equipped with the magic black box. Here they could meet their European counterparts on equal terms, the intracacies of contour, perspective and light and shade, now caught by the camera shutter with just on click.

This would revolutionise the recording of the life and times of a new world that would soon be equipped with electric light, telegraphic communications, telephones, radio and ultimately television.

Chinnery's Macao survived his 1852 death by many years, but none has served the city so well as this faithful recorder; none has captured its essence, charm and beauty, or its Iberian architectural character, as the sketches and paintings of George Chinnery.

Ultimately, it was the sale of these sketches by auction after his death, which paid his patient, long-standing creditors in India who were at last able to write off his bad debts. Chinnery the fugitive in time became Chinnery the respected, and the saviour of old Macao.

* Writer and journalist. Born in Shanghai, lived 35 years in Hong Kong, where he was editor of the South China Morning Post newspaper. Wrote several historical books, including the biographies of Chinnery and Borget. He also organized conferences about China, Hong Kong and Macao.

start p. 219

end p.