INTRODUCTION

Within the present-day layout of the city of the Holy Name of God of Macao it is still possible to discern the vestiges of its original urban structure, naturally based on the distribution of ephemeral architecture, subsequently consolidated by new buildings with different features which were to mould it definitively. Based on an organic sense of growth, the form of this city presents us with the stamp of mediaeval times which characterises the centres of old Portuguese cities. "As was to be expected, the Portuguese took their traditional form of construction with them to the East and so it is no surprise that the cities that were built there - rows of houses, churches and fortresses - should be closely related to those in Portugal. 1

In Macao, however, the presence of Chinese architectural features - particularly those relating to structural and decorative details - and the main aspects of Chinese urban structure have always been an indissociable facet of its character as a territory of Chinese influence. The Portuguese in the Far East have absorbed other techniques of building cities and expanding them, intermingling their own ideas with traditions that have also been implemented in other trading-posts in China.

View of Chin Chu: location of the Fortress. (Fig. 1)

View of Chin Chu: location of the Fortress. (Fig. 1)

In speaking of the urban origins and architectonics of Macao, we must in some way take account of its contemporaneous oriental cities and trading-posts, points of contact and/or direct influences. Naturally, this includes Portugal's chief possessions at that time: Goa, both city and state, and also Malacca, seat of the diocese under whose jurisdiction Macao remained until the creation of its own bishopric. But although they certainly derived knowledge from these two cities, the Portuguese who arrived in Macao without doubt gained valuable experience from the first settlements they established in China, as well as from the traditional knowledge of the native inhabitants.

Taking account therefore of the various cultures identified in those areas and the special features of an enduring mediaevalism, in terms of both culture and mentality, we can also understand the way in which such external influences manifested themselves in the architecture of Macao; if the Portuguese seafarers carried with them their traditional and stylistic knowledge of construction, they in turn were influenced by local forms which were better adapted to the climatic conditions.

As the Portuguese made constant incursions the "Great Oriental Empire" (in the form of both official and missionary expeditions), Chinese cities and architecture frequently influenced their vision and sentiment2: the monumental volumes and lined symmetries, the ornate decoration, the brilliant colours and materials which were incorporated into the design and organisation of the spaces in which they lived. The resulting urban image of Macao therefore originates from the coexistence of, and interconnection between, the western understanding of a lasting mediaevalism and the traditional Chinese elements with which it is filially linked.

PORTUGUESE MEDIAEVAL BUILDINGS IN A COLONIAL REGION

"Portuguese town planning is characterised above all by the intelligence of the location and the choice of design, in a unique reconciliation between organicity and rationality, an understanding of the relationship between landscape and urban functionality. In the different territories occupied by the Portuguese, there are clear expressions of what has characterised the morphology of our cities since the Middle Ages: they are presented as spontaneous organisms and as signs of a strong will, executed by hands showing great humanity. A highly monumental description of religious architecture, in accordance with the historical moment of affirmation of the Church during the Counter-Reformation and the baroque period, is in contrast here with the organic development of urban establishments, although this latter is governed by the renaissance and military notion of reason and order." 3 These words of Alexandre Alves da Costa without doubt summarise the essential point of this study, seeking an understanding of the growth and formation of the towns that the Portuguese scattered across the Far East, which served as essential experience for establishing the City in the Holy Name of God of Macao. The prime requirement was to put, as fast as possible, roofs over the heads of the innumerable families that were springing up in those towns that were prospering daily as a result of the Portuguese trading empire. Natural factors were the most important element in the genesis of those new towns, which developed as a result of two different aims: enforcing the new order, as was the case with the new towns built in Brazil, by the superimposition over and consequent obliteration of pre-existing development - that is, the elimination of towns that had been conquered; and taking over existing structures, giving them new forms by adapting them to new functions or by maintaining and extending new towns in parallel with those that already existed. In the case of the former, in a truly colonial sense, the concern was to expand into new worlds, enlarging the Portuguese empire on the new continent with the notion of demarcating force and power, in a place where the inhabitants appeared to be backward, primitive, easily dominated and lacking a society with an organised system, but where wealth, in the form of gold, lay under the ground and not on the surface. In the case of the Far East there had to be some other notion since in all the ports where the Portuguese landed they encountered well-established cultures, particularly in China. Here, sea-borne merchants were primarily interested in the spices, precious stones, cotton and silk, access to which had been denied them, due to the supremacy of Islam.

The character of the mediaeval city is defined by the attraction it exerts on rural environments, offering business and employment. The upsurge of mediaeval cities in Europe was due specifically to the development of trade which created a society that consisted of travelling bourgeoisie and merchants, who set themselves up in the trading ports where they engaged in a series of businesses connected with trade, such as outfitting ships, manufacturing rigging for sailing ships, cooperage, chart-making, etc. The appearance of this type of mediaeval city was also clearly consistent with one of its basic features: ensuring protection by occupying a position that was easily defended, such as close to a river, especially at a point where there were confluences and winding stretches of water, a characteristic of all Portuguese settlements in the Far East. And in all the towns and trading-posts that sprang up, the first step was the construction of new walls around the urban perimeter.

Goa

In Goa - which was to become without doubt the most important trading and military port in the East after being conquered by Albuquerque - the construction of new city walls was immediately put into effect under the supervision of the architect Tomás Fernandes, who reinforced the existing fortress and named it "Manuel" in memory of King Manuel. This fortress followed the mediaeval system of construction with traditional towers and turrets. Goa then witnessed the growth of its urban structure, as a result of the Mandovi (customs tax), in an extremely rapid radioconcentric progression, a perfectly natural trend in a city whose expansion came about as a result of the port and the river. Within the fortified area, Goa's main streets fanned out from the centre towards the port area in a radial form, and were interconnected by secondary streets oriented around the most important religious centres. Goa thus resulted from spontaneous and organic growth originating from a maritime trade that had had shaky beginnings, one that became established by virtue of necessity and whose aim consisted of organising new enclaves as strategic bridges for the domination of the rich market of the oriental world. The traditional formula of the mediaeval city structured around its port was quite obviously used here. The rows of houses that began to emerge were reminiscent of those in the mother country, a fact remarked on by European travellers as reported by Carlos de Azevedo, quoting Linschoten: "La ville est ornée de beaux édifices bâtis à la mode de ceux de Portugal".4 By the middle of the 16th century, Goa had already undergone an enormous change, reaching its peak only at the end of the century when churches, palaces and public buildings reflected a civic splendour that resulted from the feverish commercial activity that attracted merchants from all over the Orient.

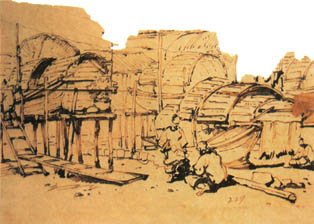

View of Chin Chu from the Fortress. (Fig. 2)

View of Chin Chu from the Fortress. (Fig. 2)

Malacca

Immediately following the conquest of Malacca by Albuquerque, orders were given for the construction of a stockade for artillery, to be built with timber reclaimed from enemy junks5. Inside it and close to the estuary, work began on a new fortress (using plans drawn up by Tomás Fernandes, as had been the case with the one in Goa) with high walls formed of huge blocks of laterite, 12 ft. wide and 60 ft. high (as recorded by Gaspar Correia, Afonso de Albuquerque's scribe)6.The fortress had a square keep topped with pinnacles "covered in lead and having all other chambers as befitted its majesty".7 The roof of the fortress was formed by a terrace used by the artillery with turrets rising up from each corner, covered in lead and tin, both of which were plentiful in the city. The original fortress was completed in 1512, six months after the conquest, and controlled the estuary of the Malacca River. Basically, the fortification encompassed the São Paulo Hill and took the form of an irregular pentagon with one side facing the sea. In view of the pressing need for defence, a primary protective shield was erected in approximately 1520, which surrounded the entire district in the form of a timber palisade. It was only in the second quarter of the 16th century that the city was walled; the walls of the great fortress (later known as the "Famous Fortress")8 began from that tower and its adjoining main buildings, and part of those walls were built of lath and plaster. One of the main architects of the "Famous Fortress" was João Baptista Cairato (Giovanni Battista Cirati), the "man from Milan". Lath and plaster replaced the original construction in 1539 but Cairato's final drawings, in the Renaissance style, only arrived around 1569. For Malacca, Cairato proposed that the fortress should be enlarged to the east with the lath and plaster walls replaced by stone, but the work was never carried out. This decision later compromised the city's defence when under attack by the Dutch.

Therefore Malacca kept expanding along the river, with its nucleus forming naturally at the estuary, since trade was the basis of its economy. The construction methods used for the pre-existing houses, which were high off the ground with walls of laths finished in a type of rough-cast plaster and covered in palm leaves, were continued by the Portuguese who slavishly adopted the same forms. In fact, in such an extremely hot and humid climate, only local building methods enabled the provision of necessary ventilation and suitable protection from the intense heat of the sun.

Within the walls on the left bank of the river, the city's political and religious centre began to develop as it had in the times of the Sultanate. It retained the appearance of a perfect mediaeval city with a well-defined military and religious personality (as a manifestation of Lusitanian authority) encompassing the main public institutions and the "old fortress", the residence of the military leaders, and the administrative centre. New buildings there gradually took on the traditional Portuguese form of stone construction, in this case laterite, which was easily worked. In addition, the structures were different in certain parts of the city: the Christian quarter inside the walls had a planimetry of the nuclear type, starting from the São Paulo Hill, dominated by the church and college of Nossa Senhora da Anunciação (the present-day ruins of São Paulo) which belonged to the Companhia de Jesus9; outside the walls, the Chinese and Indian communities built the suburbs on more geometric lines, an arrangement that was dictated by their beliefs and traditions; along the river, the Sabak houses on stilts created a linear structure, and the Malays of Ilher presented an uneven image in the arrangement of their shacks. The overall aspect was therefore the result of the integration of the different parts, identifying the originality of this trading potentate and major religious centre where the mixed population10 benefited from a climate of increasing prosperity under Portuguese guidance.

TRADING-POSTS IN CHINA

Taman

As is already known, the first contact with Chinese territory was made by the factor, Jorge Álvares, on the island known at the time as Taman (the present-day Leng Teng). The first thing the Portuguese saw on the banks of the Pearl River estuary were fields of rice planted over vast areas; many of the islands they had visited previously appeared to be uninhabited, although their anchorages were ideal places for fishermen or pirates to stop and rest. Other islands showed signs of settlement, with villages demarcated at the foot of a hill or granite promontory, always facing the sea and always enveloped in leafy trees which ensured close contact with nature. Taman was situated about one hundred kilometres from Canton, fifteen kilometres north of Lantau (an island that was to be absorbed into the British colony of Hong Kong) and fifteen kilometres from Nam Tau (or Nan To on the Chinese mainland). As Castanheda, Góis and Gaspar Correia had already noted, it was heavily populated, relied on its port, and controlled all marine and river traffic in the area. Here Álvares was to receive a very warm welcome, which promised an amicable future between the two people. With the arrival at the port of Peres de Andrade, in 1516, a group of Portuguese settled here to trade and built themselves houses. These houses were a result of the immediate agreement of the Superintendent of Canton to the first request made by Fernão Peres to construct a warehouse to protect their goods from bad weather and theft. Little is known of that first Portuguese settlement, but fragments of Portuguese inscriptions on monuments remain there, possibly originating from the fortress that Simão de Andrade decided to build in 1519, on the pretext of providing defence against pirates and along lines similar to those in the cities described previously. Although basically consisting of timber, this fortress had substantial stone bases and porticoes, therefore some remains have survived until now. Inside the walls was an irregular urban layout with buildings that were simple but long-lasting, as described by an author in the 19th century: "The streets are all paved in stone and most of them are full of twists and turns, hindering the progress of hawkers and craftsmen, making it difficult for carriages to pass"11. Because the traditional Chinese city layout is based on regularity and geometry in the definition of the street grid, the assumption may be justified that in certain areas Leng Teng had acquired a western mediaeval framework. When the Portuguese were driven out of the island in 1521, the area where the Portuguese community had established itself was completely destroyed, but the footprints of the "men with long beards" were to remain there forever.

Liam Po

The first Portuguese arrived in Liam Po in 1524, having been driven away from Taman. Despite the imperial orders prohibiting trade with the falankis 12, some Chinese "migrants" bribed the mandarins and managed to find a place in which to settle the foreigners, on whose trade they depended. And so, in a hidden inlet at the mouth of the Fuchun River13, in the province of Zhejiang, they built a port where trade soon began to flourish.

Lath and plaster wall in Chin Chu. (Fig. 3)

Lath and plaster wall in Chin Chu. (Fig. 3)

At the entrance to the harbour bar fifteen kilometres off the coast, they found two islands, between which "passes a channel of little more than two rifle shots in width, with a depth of between twenty and twenty five fathoms; in parts there are coves affording good anchorage and cool freshwater streams flowing down from the top of the sierra through areas thickly wooded with cedar, oak and wild and cultivated pine, which provide many ships with yards, masts, planking and other timbers, completely free of cost."14 These islands, "that landlubbers and sailors plying the coast refer to as the gates of Liam Po" 15, served as natural protection, closing off the harbour and making it an ideal place for a settlement. The islands provided, on the one hand, refuge from institutional authority, and, on the other, protection against attack from the sea (in an era of constant piracy). The Portuguese established lookout posts on these two islands and sailors almost always had to stop there before going ashore.

It is also difficult to discover the truth about this former Portuguese town in the Far East. Contemporary descriptions are always very vague and generalised and the remains have almost all disappeared after the settlement was completely destroyed by the Chinese in 1548. According to Montalto de Jesus, in the 19th century there still remained "... the ruins of a fort in Chin Hae that was clearly of European construction, with the Portuguese coat of arms engraved on a door and the actual temple near the Portão da Ponte which was attributed to the Portuguese in 1528 as being the Associação de Recepção de Estrangeiras (Foreigners' Reception Association)."16 As had been the case in Taman, we understand that one of the main intentions of the Portuguese when arriving at such a place was to build as quickly as possible a strong protective wall in order to safeguard their people in these foreign lands whose residents were hostile towards them (with attacks by pirates or disaffected mandarins always being a possibility), as well as to demarcate their settlement.

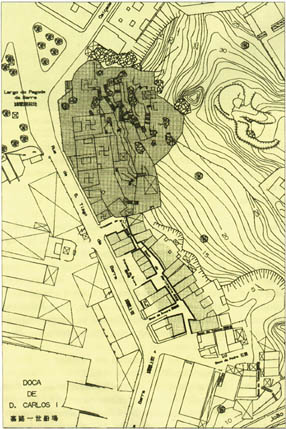

Location of the temple of A Ma and the Chinese village near Barra. (Fig. 4).

Location of the temple of A Ma and the Chinese village near Barra. (Fig. 4).

The growth of this town did not follow rules or pre-established plans. Trade was initiated right from the beginning and the trading-post continued to expand in the form known to all Portuguese: ground a central street, the "rua direita", very common in the towns of mainland Portugal, where the main civic and religious buildings were situated, with other streets and alleys running off it. In his report of the reception given to Antonio de Faria following the victory over the pirate Coja Acém, Fernão Mendes Pinto provides a description of this street: "After landing and having been congratulated on his arrival (...) they took him to the church following a very long street, completely closed in by pine trees and laurels, canopied above by numerous pieces of satin and damask. There were frequent tables bearing silver pans with many scents and perfumes, and very expensive concoctions. And almost at the end of this street was a wooden tower built of pine, painted like stone, which at its highest point had three turrets: in each one was a golden weathercock with a white damask flag and the royal coat of arms outlined on it in gold; and in a window in that same tower were two young men and a lady, weeping for days on end (...)".17 According to Pinto, at that time there were six or seven churches in Liam Po, including the parish church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição which opened onto Rua Direita. Nearby was a large square, which was well defined by the houses surrounding it. There were more than one thousand houses in the town and many of them were large and well-appointed.

Without any doubt, this town had the appearance of being "the best and richest port known at that time throughout the region" 18, and with its growing importance the local people became increasingly inclined towards the mediaeval traditions and customs of western society. The description provided by Pinto of the reception given to António de Faria is so unusual that we cannot resist giving another transcription of his "Peregrinação (Pilgrimage)"where the reasons for the mediaeval festival became absorbed in the daily lives of these "exiles": "When António de Faria was leaving the place they wanted to carry him under a rich canopy that six of the most important men had given him (...), and there was much dancing, ball playing, merry-making and games, and entertainments that the people of that country who were with us were playing, some begging us, others forced out of pity, acted like the Portuguese; and all this was accompanied by many trumpets, pipes, flutes, harps, fiddles, piccolos and drums, with a labyrinth of voices so loud that it all seemed like a dream"19.

"Pan handle" gable on the temple of A Ma. (Fig. 5)

"Pan handle" gable on the temple of A Ma. (Fig. 5)

Throughout these descriptions runs a sense of the prosperity and security that permeated Liam Po, a splendour that originated from commerce with Japan. In 1544 the municipality was established, with a town council, magistrates, auditors, judges, counsellors, a chief ombudsman for the deceased and orphans, scribes, notaries, etc. The Misericórdia (a charitable organisation) permitted the expenditure of vast sums of money (around thirty thousand cruzados annually) for the maintenance of churches and hospitals for the poor. Three thousand Europeans (but only around 1200 Portuguese, many of them "married" to locals) lived there in more than one thousand private houses, a clear indication of the buoyancy of this trading centre. But "The Portuguese were so haughty and full of themselves that they spent all their money on constructing buildings and palaces in countries that did not belong to them but to idolatrous people, with whom they had few dealings, without considering that they could only stay there as long as the local people wanted them to if they continued to involve themselves in trade in order to increase their wealth." 20 And indeed just as the town was created, so it was dismantled - since, as Pinto remarked, "things in China are far from certain". In 1545, just days after a group of Portuguese attacked the village of Nou Day (fifteen kilometres from Liam Po) in retaliation for the robbery of Lançarote Pereira by some Chinese, a fleet of three hundred junks and sixty thousand Chinese attacked the town, destroying it completely and slaughtering a large number of Christians who were living there. They also set fire to all the ships anchored in the port.

Chin Chu

Following the demise of Liam Po, only a few survivors remained and these fled wherever they could find refuge, crowding onto junks that had been saved from destruction. In the province of Fukien, a mountainous region 1500 kilometres from Liam Po that had been visited in 1518-19 by Jorge de Mascarenhas, the refugees established themselves in the village of Chin Chu, close to the town of Amoy (nowadays Xiamen). Around eighteen months later, that town would be dominated by the vibrant commerce established immediately by the Portuguese, who, in view of the disappearance of the earlier trading-posts, needed to set up a large warehouse there for their merchandise from Malacca.

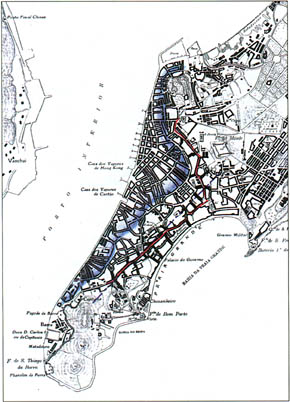

Map of Macao, c. 1912. Location of the villages of Taipa and Coloane in Macao (Fig. 6).

Map of Macao, c. 1912. Location of the villages of Taipa and Coloane in Macao (Fig. 6).

If little is known about the earlier settlements, almost nothing is known about this one - a strange state of affairs, considering the vitality that it acquired. From its location we can deduce that it was sheltered from the north-easterly winds that are so troublesome in this region, being situated in an inlet, the Bay of Liu Loo. According to an author writing in the 19th century, even at that time there were still"the remains of a fortress, ashlar masonry and Moorish-style buildings" 21,which is equivalent to describing a medieval military structure, with large towers and semicircular turrets dominating the walls. Similarly, the same author was convinced that the ruins showed signs of being "the work of hands that were not Chinese" 22. This clearly must have been the case since we have already seen that the trading-post grew rapidly. The experience of previous misfortunes must have led the Portuguese at Chin Chu to give priority to fortification of the town, albeit on a small scale. We believe that this fortress was still being built around 1549, since it was at that time that the town was destroyed; as may be deduced from Fernão Mendes Pinto's account, this happened extremely rapidly, and would not have happened if the walls had already been reinforced. Furthermore it would certainly not have been possible to build something on such a scale in only thirty months.

In the place where the city must have stood is the small village of Au Tché to the east, which is relatively close to Chin Chow (as it is pronounced in Mandarin), in a favoured position on the River Chin estuary. Nowadays the bay has silted up, but in those days, according to residents, it could take vessels of many tons. For the Portuguese refugees this would be the ideal location for a port that was sheltered but that would enable a quick escape in the event of an attack from land; in addition, its location enabled the founding of a settlement that was higher than the port and offered a complete view of the surrounding countryside (see Figures 1 and 2).

As witness to that fortification, even today there are sections of large walls that, according to the inhabitants, originate from the time of the Ming dynasty when some foreigners settled there. They are made from lath and plaster using a traditional Portuguese technique, with their various layers well compacted and the characteristic holes left behind from shuttering (see Figure 3). The fortification consisted basically of lath and plaster walls, but as far as possible was constructed with granite blocks23, which explains its continued existence (although naturally in ruins) even in the last century. With the levelling of land that has been carried out here in recent times, and due to the need for use ready-cut stone - for the pontoons and the former coast road near the port (nowadays covered over) - the destruction of the remains of the port and the commercial city has been taking place inexorably.

Because of his acquisitive nature, Aires Botelho de Sousa, ombudsman for the deceased, succeeded in compromising the future of the Portuguese community by terminating relations with the local people. With this came the cutting off of supplies needed by the Portuguese who were then forced to raid neighbouring villages in order to obtain provisions. This action caused a reaction on the part of the Chinese authorities who mercilessly drove out the Portuguese.

However, there was a need to carry on commercial exchanges in those lands of the Far East on which the whole of Portugal had come to depend.

Shangchuan

Ridge decorations on the pavilions of the Temple of A Ma (Fig. 7)

Ridge decorations on the pavilions of the Temple of A Ma (Fig. 7)

The Portuguese were determined to find a new port in Shangchuan, an island to the south of Guangdong province. At the same time it was necessary to attempt the conversion of the natives in order to try and renew their confidence in the "falankis" by introducing them to God's word. This heralded the appearance of the major figure of St. Francisco Xavier, "the apostle of the Orient," who died there on the 27th of November 1552 at the age of 52. It is clear that lack of security had become a reality and the Portuguese were not permitted to construct large buildings. It can be confirmed, therefore, that the Portuguese did not manage to establish a permanent settlement on Shang Chuan, a port where a city could have been founded. Any structure had to be strictly of a short-term nature since their stay on that island was thought of only as a means of awaiting the favourable monsoons that would allow them to continue their route between Malacca and Japan. Therefore during the three or four months that the Portuguese generally spent there, their dwellings consisted of huts made of tree branches and covered with matting made from leaves. Bamboo was also used, 24 being an extremely versatile material, and the Portuguese had learned about its use for construction from the Chinese during the several years they had spent in the region. In other cases, a system of tents made from the oars and sails of boats was used, as described by Faria e Sousa: "During the 1550s the Portuguese merchants frequented the island of Sanchuan (or Sancham as they called it) at the gateway to China, near Canton; but they had no fine houses, only shacks made of cane, and used the sails of their boats to build shelters that lasted as long as they stayed there carrying on their trade" 25. As each ship carried a set of sails26, this system turned out to be highly practical for the sailors who had mastered the techniques of tension and traction, easily adapting these to the execution of this simple type of architecture.

Lampacau

From here the next leg was Lampacau (Long Pek Kau), an island about 30 kilometres north east of the Shangchuan, south of the bay of Hsing Shan. In 1555, with the arrival of the Jesuits from the Japan Mission, this port also started to expand and the island, which had been uninhabited, was gradually occupied by straw houses and even had its own church. By the middle of 1556 there were already some three hundred Portuguese living there and by 1560 there were more than five hundred who were compelled to pay dues in order to remain there. The port started to accept ships from Malacca in search of trade with Canton whose trading ports were again open to foreigners27. As in Shangchuan, the Portuguese in Lampacau did not risk constructing large buildings and never established an urban structure as such. Although their presence had a greater sense of stability, there were still similarities to the situation in Shangchuan and huts were built from tree branches and bamboo, covered in tree bark. Since the Portuguese were obliged to keep their vessels offshore, the building of such practical yet fragile tents was not as common here as it had been on the previous island. It was only through the influence of Leonel de Sousa, commodore of the Japan fleet, that the requirement to remain offshore was abolished. This was also a time when trade was beginning to be carried on in another place, where there was the promise of a legal guarantee of a permanent settlement. By 1553, the Portuguese had set foot on the soil of Macao.

MACAO- TOWN PLANNING AND ARCHITECTURE

This study aims to cover the origins of Macao and to reflect on them, from its first tentative steps towards becoming an urban settlement until it fully assumed the structure of a city. Beginning in 1552 with the first Portuguese contact with the peninsula and adjacent islands, and until the second decade of the 17th century, this period unfolded in three phases which we shall consider separately: occupation, stabilisation, and certainty of the future.

Occupation of the area

Returning from their voyage to Japan28, we know that the Portuguese sailors headed for Shangchuan were in contact with Macao from early on. This contact was reinforced with the resumption of legalised trading exchanges with China, and, upon their return from the market in Canton (the largest in Southeast Asia) to Lampacau, the Portuguese actually sought permission to land in Macao, as confirmed by Chinese documents: "In the 32nd year (1554) the foreign ships started to ask verbally, because their ships had been battered by the wind and waves, if they could be loaned the land of Hou Keang (Macao) in order to dry all the tribute goods that had been soaked"29.

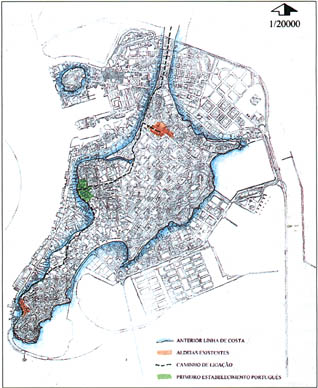

Macao was a small peninsula that offered excellent anchorages, especially on the northeast side, sheltered from strong winds and typhoons. Surrounding it were several islands: Patera (the Island of the Padres or Lapa), Tomei (King João or Ma Carira), Tai Vong Kam (or Montanha), Kai Keang (or Taipa) and Kai Ou (or Coloane). These islands were uninhabited, although on occasions they served as a refuge for pirates. In Macao meanwhile, two Chinese villages already existed with their "chi tong" (ancestral pavilions where monuments to the villagers' forebears were worshipped), their shrines and their temples. In these, timber was naturally the material favoured for construction as well as brick and tiles baked in kilns, exactly as in other architectural examples to be found in that country from the period of the oppressive yet vigorous Ming Dynasty. In comparison with architectural examples from earlier times, the construction norms of the Ming period, without doubt China's highest point of achievement, is the most representative range of architecture in China and its influences also reached this peninsula.

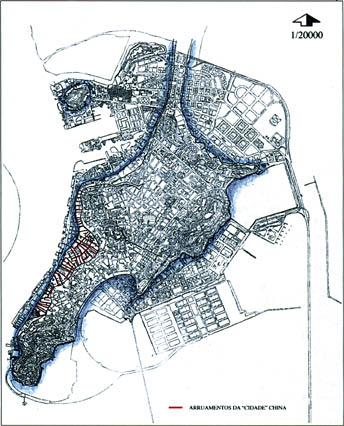

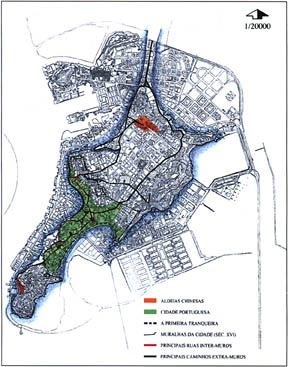

The growth of the Chinese city and the transformation of the peninsula in the 18th century. (Fig. 8)

The growth of the Chinese city and the transformation of the peninsula in the 18th century. (Fig. 8)

In Barra, the southern extremity of Macao, was the temple of Ma Kok, the oldest (built in veneration of the goddess Ama or Ma) which is believed to be the origin of the peninsula's name. At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese, the temple of Ma Kok was organised in a series of small pavilions, highly representative of the Ming style, arranged in perfect formation along the hill of Barra, fully integrated into the surrounding natural environment and set among the area's rocky outcrops. The temple's architecture developed not as a function of itself, but of its surroundings. This was a feature that was peculiar to Chinese architecture, which made itself understood as being intrinsically linked to its natural surroundings, emphasising not its individual value but its communion with nature. Built early in the Ming Dynasty, the temple remained untouchable until the end of the last century when repair work became necessary and was carried out at the expense of the merchants of Fukien. Nowadays it is somewhat larger than it was but has retained its original appearance and character. There are the same roofs in "xi shan" style (a double roof where originally the lower one was nothing more than a cover for a gallery surrounding the main building), in "ren xi" style (pitched roof), the latter with a variety of gables and ridges30 (also adopting the form of "juan peng" which consisted of the removal of the ridge by rounding off the roof at the highest point) which lent a sense of energy and extraordinary movement to the building, attracting the faithful and awakening in them a powerful religious feeling. The expressive force of the "paifang" (the ceremonial arch used only in the portals of the most important buildings) in the second pavilion makes this the centre of adoration of the entire temple. Poems were engraved in the granite rocks, all of them extolling the beauty of the place.

Around this temple arranged in a relatively regular fashion was the fishing village, inhabited by fishermen originating from the province of Fukien31.It consisted of modest dwellings with one or two floors (simple and easy to build), between which were narrow streets paved with large slabs. Arranged in rows on the bank, these houses maintained the traditional structure, formed a cohesive unit at the foot of the Barra hill which enabled them to retain their urban layout until present times (see Figure 4). The village benefited from excellent "feng shui" because it was set in an area offering a high degree of natural comfort - sheltered, as it faces southwest, protected by the hill from the cold northerly wind, and close to the water. "Feng shui", or Chinese geomancy, is a traditional millenary science that attaches special importance to appearance, legend and myth, in which everything has a symbolic explanation based on the concept that the natural or supernatural implications of any act should be carefully scrutinised. "When a group of human beings settle in an uninhabited area of the earth and decide to build their homes, construct a city or carry on their agricultural activities there, that group has an effect on the surrounding environment, changing it. And according to the Chinese doctrine of "feng shui"32 this, in turn, reacts on those who have brought about the changes. The reaction will be positive or negative according to whether or not the laws of nature have been respected"33. Although it embodies superstitious justifications in relation to the unknown, we find in this science a great desire for integration with nature and well-being in relation to it.

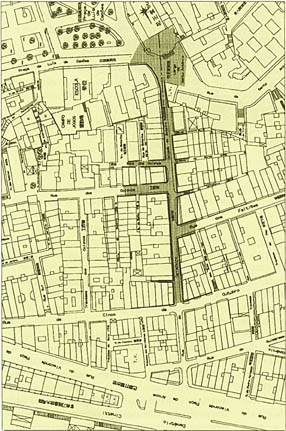

The Calçada do Botelho. Macau's first main street. (Fig. 9)

The Calçada do Botelho. Macau's first main street. (Fig. 9)

To the north of the peninsula, close to Mong Ha Hill and extending as far as the Ribeira de Patane, is Mong Ha Chun (the village overlooking Ha Mun)34 which has an essentially rural character. This is the oldest village in Macao, where the descendants of the inhabitants of Fukien35 came to live early in the Ming dynasty having fled the invasions that established the dynasty. They used the flooded fields to grow rice and "tong choi" (an aquatic plant) but the location of the village was also dictated by "feng shui" since, being at the foot of the hill, it offered protection from the northerly winds, enjoyed sunshine all year round and was safe from flooding. These conditions were the deciding factors in the choice of a site for any village, town or city, once it had been determined that the site was not excessively high or low and was able to rely on a good water supply and drainage facilities; it was necessary to enable the building of canals in order to have a constant supply of water, and these canals were constructed so as to avoid the danger of flooding36. The place was a perfect haven, a veritable swallows' nest37,"low and sheltered by favourably positioned hills, one of which skirted it like a delicate lotus leaf with a long stem, represented by the isthmus linking Macao with the former island in the district of Heong San Un" 38. Clearly such a place required the building of a temple, a task that was undertaken by the villagers of Mong Ha, inspired by the auspicious appearance of a statuette of Kun Iam, goddess of mercy. This temple consisted of small buildings arranged in horizontal lines and small parallelepiped structures, of which one example remains today. Naturally, also in accordance with the traditions and characteristics of the Ming style, the appeal to the visual sense was a constant factor as well as the use of a cunning decorative features with innumerable variations, captivating to the human eye39. But this architectural decoration bore a very special stamp as it was intrinsically linked to the structural elements rather than simply appended to them, serving a practical purpose as well as forming an integral part of the architecture, instead of mere ornamentation.

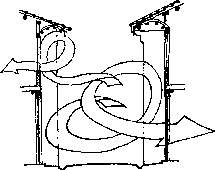

Artist's impression of a tree-bark roof. C. Baracho (Fig. 10)

Artist's impression of a tree-bark roof. C. Baracho (Fig. 10)

The village sprang up around this modest temple (later to be smothered by the emergence of Kun Iam Tong to the northeast) were, at that time, built of bamboo (which was plentiful in Macao), covered in ola (local palm leaves), and roofed in rice thatch. Later on, these houses were gradually replaced by groups of small, elongated buildings arranged on a central axis connected to courtyards, galleries and rooms. The basic plan of a house was governed by the ethical principles of Confucius40, which reflected the power and authority of the patriarchal structure of the Chinese family following a rigid hierarchical system. The family house was therefore the best form in which to express those concepts. The distribution of the areas comprising the house was along an axis that imposed symmetry on the whole. The rooms opened out onto courtyards41, the largest room was always reserved for the oldest member of the family and was located to the north, while to the east and west were those intended for the younger family members. In each of the sections, columns divided the inner area and the structural elements were well defined. As in the rest of the province of Canton,where the climate is hot, these houses tended to have several small courtyards in order to enable the free circulation of air. The main entrance to these houses always faced south and was the only one to have any form of decoration, indicating the importance or status of the house. This decoration sometimes included inscriptions or verses on the door-posts or pillars on both sides of the door, which would bear ornamental motifs expressing the philosophy or beliefs held by the family42.

Such features were to become a distinguishing characteristic in Macao, and even in the 19th century, when dwellings were built with hybrid features, they were also in accordance with the perfect typology of the Chinese courtyard-house.

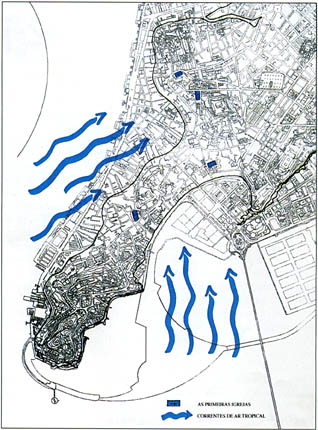

The Portuguese occupation of the peninsula began at the foot of the hill on the site of the present Jardim Camões (Camões Garden), an area situated in the middle of the road connecting the Isthmus and the Barra (the two ends of the peninsula) and halfway between the two existing villages. In addition to having a direct link with the sea, this location also enabled them to barter goods directly with the local inhabitants, on the one hand with the village near Barra, which was also involved in shipping, and on the other with Mong Ha where goods that had come overland could easily be collected. It was also an advantage if those going to the village near Barra were forced to pass through the Portuguese settlement, facilitating trading exchanges. The location was ideal: as well as having commercial advantages, it also provided natural protection from the south-easterly winds (see Figure 6). Evidence of this fact was the construction of the first church (on the site of today's Santo António) in the area during the early days of the settlement, as well as the street names, Rua dos Mercadores (Street of the Merchants), where trading took place, and Rua dos Colonos (Street of the Colonists) which marks the fact that the earliest colonisation of the peninsula by the Portuguese began there. This first settlement was laid out around a central street (coinciding with the present-day Rua do Tarrafeiro), which led to the afore-mentioned church, and had smaller streets branching off on both sides like the backbone of a fish.

Their experiences in all their previous settlements in China led the Portuguese to proceed with great caution in occupying Macao. The Chinese authorities did not view favourably the establishment of another port while trading was still going on in Lampacau. From the beginning, the continued existence of Macao was uncertain; therefore any buildings had to be considered short-term in nature, as had been the case in Shangchuan and Lampacau.

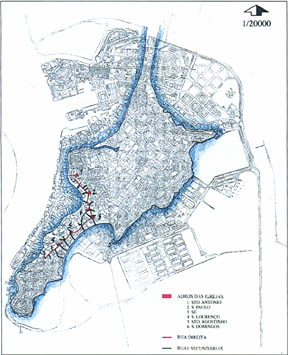

The "Rua Direita" (main street) and Macao's secondary roads. (Fig. 11)

The "Rua Direita" (main street) and Macao's secondary roads. (Fig. 11)

The earliest examples of architecture in Macao carried out by the Portuguese employed practices learned during previous periods spent in the East. Their first experience was gained in India during initial contact with the Goans. Adaptation to local materials and the technology developed in order to overcome the climatic factors there had been of major importance since they came across similar materials used locally in subsequent trading-posts. However, the climate varied from region to region, not so much in terms of temperature, but in terms of types of adverse weather conditions. We know therefore that when Portuguese mariners reached the anchorage of Ama they were already skilled in the use of bamboo and various timbers, in weaving palm leaves, using animal skins, etc. Although destined to rapid disappearance because of local climatic features, with constant typhoons during the summer months, the earliest forms of short-term architecture in Macao demonstrated the facility to learn and acquire the lexicon of construction combined with the need to adapt to the standards of comfort that the Portuguese felt to be a necessity. For obvious reasons, this "architecture" no longer exists today and unfortunately we have no definite documentary evidence (although some contemporary descriptions exist, as already mentioned) of these buildings. However, we are convinced that, considering the methods of constructing temporary structures still used today, as well as the consistency in Portuguese architecture across the regions in which they settled and the aptness of the building materials to the local climate, the first buildings constructed by the "falankis" could not have been the work of anyone else. The following is a presentation of three methods of construction that were most definitely used.

Artist's impression of one of the early structures in Macao (short-term architecture) (C. Baracho). (Figs. 12 and 13)

Artist's impression of one of the early structures in Macao (short-term architecture) (C. Baracho). (Figs. 12 and 13)

The first structures the Portuguese built in Macao were huts made of bamboo whose vertical sections were staked into the ground and fastened by reeds arranged horizontally and positioned close together, secured by means of tape made from the bark of the same reeds or from palm leaves. For larger houses such as the "registry" (where the goods were entered in a register and where the ships' masters met), yards and brooms from on board ship were used for the pillars and main beams. The walls consisted simply of the juxtaposition of bamboo slats, which enabled the occupants to benefit from a through draught, when necessary minimising the dreadful humidity caused by climate changes (especially due to the rains). Buffalo hides43 were added to make the huts watertight; these were so effective that the rainy season was referred to simply as the cold winter wind (see Figure 12). These skins were also used on the roof, placed adjacent to the structural beam and secured using half bamboo canes which gave the structure additional support (see Figure 13). The doors and windows were made in the same way as the walls, but generally with the canes positioned vertically and the hinges made out of the mortise of the end cane which was longer and attached to the wall of the house (see Figure15). The disadvantage of this system was having to cope with the unpredictability of the weather, since the skins could not be used constantly as wall coverings because they absorbed too much heat, causing a greenhouse effect. A variation on this type of construction was also based on bamboo but covered in tree bark (see Figure 10). This material was easier to obtain since, like bamboo, it was a direct natural resource with the further advantage of being able to remain where it had been applied. While offering protection from the wind and intense rain, this type of construction succeeded in maintaining a bearable temperature inside the dwelling as well as providing vents that ensured a through draught. These vents were generally located at the top of the walls and immediately under the roof. However, this system was not as cool as the free bamboo structure, and the tree bark acted as a fixed material. In the same way, these pieces of timber were secured using half bamboo canes; on the roof, they were held down with evenly arranged layers of tree bark in order to avoid large unprotected gaps of bamboo cane and to prevent them from coming loose. To complete the assembly, large bamboo trunks reinforced the structure and counterbalanced it against the force of the strongest winds.

These two forms of construction led to the adoption of a system that attempted to solve the problems they gave rise to. The Portuguese settlers went on to use a type of wall made of wicker consisting of palm tree leaves or bamboo canes (broken and fashioned into strips). The walls that were constructed in this way were extraordinarily fragile and therefore it was necessary to reinforce them with a cane structure - based on the principle of the first method described - creating a type of wall "sandwich". The roof consisted of a thatch made of palm tree leaves, but in view of the species found in that region and the relatively limited number of trees, the previously described tree bark system was more often used.

Development of the city of Macao by the mid 17th century (Fig. 14)

Development of the city of Macao by the mid 17th century (Fig. 14)

Whenever possible, such structures were raised off the ground, but this depended on how much time was available for their construction. Since the third method was a more painstaking and elaborate system of construction, it must have been employed only when there was ample time, or rather, at a stage at which the Portuguese had greater confidence in their ability to stay in that area. The system of raising the buildings off the ground originated from experience gained in Goa and Malacca, where it offered an escape from termites and other destructive insects, and enabled the creation of a lower air chamber which allowed air to circulate, keeping the interior cool and well-ventilated.

Little by littles confidence in the place became established and a need was felt for buildings that were more dourable. Therefore, whenever possible, the walls were replaced with bricks made of black clay, a material commonly used in that province. The Monografia de Macau informs us: "The Deputy Prefect of Coastal Defence, Uong Pak consented. (referring to the first landing by the Portuguese in Macao). In the beginning they only built thatched huts, but the merchants who had the monopoly on ill-gotten gains gradually brought in glass and concave tiles, beams and laths for building houses. The 'fat long kei' could then settle in a disorderly fashion. The high timber columns and the raised beams met as closely as the teeth of a comb, each in front of the other 44."

It was after this point that construction began to display features that allowed for a level of development that was in keeping with the growth of an expanding urban structure. This situation was echoed in other factors that were to contribute to the definitive Portuguese presence in this area.

Stabilisation

"In time, their continued presence became an accomplished fact. Consequently, the arrival of the foreigners to live in Macao dates from the time of Uong Pak", reports the Monografia de Macau, which explains in a somewhat incomplete way the settling of the Portuguese mariners in this area. It was, in fact, at this time, in 1557, that the Portuguese obtained from Kio Sing the "golden insignia45" signifying permission to settle permanently in Macao, although they paid "ground rent46" in the beginning. But the Portuguese presence in the region did not make its mark only on the little peninsula; it had already extended to the district of Heong San (or Hian Chan): "The second advantage we gained was not only that of absolute control and independence in the Peninsula and the city of Macao, but also over a large area of the island of Ansam, captured by the Portuguese armed forces (...); and the Portuguese had several estates in that territory from which they obtained a great deal of produce necessary for their subsistence, without depending on the Chinese47 at all".

Artist's impression of one of the earliest structures in Macao

(C. Baracho). (Fig. 15)

Artist's impression of one of the earliest structures in Macao

(C. Baracho). (Fig. 15)

A new age was now dawning for this Portuguese settlement and for its architectural development. "On this island and port of Macao, the Portuguese stayed for several years in the same houses made of straw, remaining in the same place because the land was good and the port was good for ships; they later made strong houses with tiles and married the local people, being ruled by their own chief citizens whom they elected and who attended to matters of government, in peace and union with the Chinese, paying them their dues, assisting them, and imparting knowledge to them, as their remaining there depended on this; they took charge of the markets and drew from everyone the money that was necessary for their expenses and offered to use for these 100 per cent of the money that had come from India, something that was most extraordinary." 48 We therefore know that the stability they enjoyed came at a price, so that the Chinese profited doubly, since in addition to the ground rent they collected, the Chinese had the right to sell the Portuguese the products they needed49.But as we have seen, the Portuguese were concerned to maintain a level of friendship, however superficial, as that was the only way of succeeding in securing the establishment of a trading-post which they wished to maintain at all costs, in view of previous failures. Lampacau did not guarantee a permanent future, a fact that was later confirmed in 1560 when it was abandoned. But at that time, Macao had already been "conquered"! Albuquerque's original idea, used previously in Goa and Malacca, of encouraging marriage between the Portuguese and local women as a way of strengthening the bonds of friendship, was taken up once again50; and because of the need to structure this growing community, a regional government was quickly formed led by the Commander-in-Chief of the voyage to Japan. The distribution of houses in the settlement took place under his supervision, as their allocation had previously taken place in an anarchical fashion, as described in the quotation: "... each one taking the site he wanted ..." Faria de Sousa provided confirmation of this: "Everyone started building a house wherever and however he wished because there was no-one to administer the land...". 51 The first mark of true urban organisation in Macao effectively appeared only after 1557. From 1558 onwards, the building of churches (which always required the highest points for their location) and their churchyards helped in the structuring and distribution of the city. As we have seen, this began near the Camões Hill by the Inner Harbour and close to the church of Santo António. Spontaneous town planning, a feature of the Portuguese tradition of always clinging to its customs (as long as they were beneficial), took up again here what had already been practised in other Indian and Asian trading-posts. Knowledge of new urban planning methods in Europe had not reached these men who had ventured to these far-flung outposts. The priorities of the court could not take that direction since it was essential to base stability on commercial dealings. Until then the Portuguese presence there had been somewhat fragile, especially in China. Here the Portuguese encountered a culture that was extraordinarily strong and exaggeratedly xenophobic; because of this, it was not possible to aspire to a direct transposition of western concepts. It should also be taken into account that by now these were not people who had arrived straight from Portugal with the intention of settling, but men and women who had come from Goa or Malacca. That is to say, a new city was formed, ruled by principles that had already been modified and/or adulterated in relation to the values initially brought from the mother country. However, there always remained the striking feature of popular knowledge learned through many centuries of development. There was a reason for the fact that even in Portugal mediaevalism persisted when other European countries ventured on towards new ideas and experiences. In addition, those who settled in Macao were not just Portuguese but also Malayan, Hindu and Kaffir merchants, 52 as well as Chinese who arrived daily in increasing numbers. This gave rise, to a certain extent, to diverse conceptions of future ideals for the settlement's growth.

We are not going to embark here on a separate analysis of town planning and architecture, as they are intrinsically linked by the very circumstances under which they were created. The need to draw Christians into a house of God quickly led to the building of churches, and so the first chapel of Santo António, patron saint of Portuguese sailors, 53 was built on the highest point of the territory where the Portuguese had established themselves. This was founded in 1558 by Jesuit missionaries from Japan, and, together with the houses built around it, was the first religious nucleus on the peninsula.

In 1565, the priests Francesco Perez and Emanuel Teixeira and six other Jesuits founded a small hospice for missionaries from Japan close to the chapel of Santo António. This would later become the Colégio of the Madre de Deus. Adjacent to the hospice was a small church, which could accommodate three hundred worshipers.

At that time the population was fairly small, in 1562 comprising around 800 Portuguese54, many of whom had come from Lampacau when the port there was closed in 1560. Until then, the houses had been able to expand, with large gardens in front, although no one had major aspirations to build palatial houses as had been the case in Goa and later in Liam Po.

In the beginning, the settlement had developed in the low-lying area near the port. It then took a new direction, expanding towards the south via a single street which soon met the peninsula's natural axis. The Rua de Santo António, and later the Rua Central, formed the same "Rua Direita" (main street) found in so many Portuguese towns. This urban "plan" included, on the one hand, the idea of structuring the main street of the settlement by integrating it into the natural form of the land, therefore creating organic growth, and on the other hand, the notion of ensuring that the city had an orderly symmetry. Unlike Goa and Malacca, its expansion had not been radioconcentric but linear, and in the form of a fish spine (see Figure 11). In the following period we shall see how that form was well demarcated.

Houseboat on dry land. Drawing by George Chinnery. (Fig. 16)

Houseboat on dry land. Drawing by George Chinnery. (Fig. 16)

At that time the houses were arranged in an orderly manner but as yet without any unifying element and therefore without anything (except the already existing church of Santo António) that could lead to the formation of small nuclei, as was to happen later. In any case, the city continued to grow, thanks to the credibility gained by the imperial authorization. The bamboo used in earlier constructions was replaced by timber partitions, for which a variety of oak was the most common wood. As we have seen, the Chinese gradually supplied the foreigners with bricks and concave glass tiles, (very similar to the tube-shaped Portuguese tiles) which enabled the building of houses that were much more resistant and more comfortable. At the same time, these materials were very similar to those used in Portugal for general construction, which enabled a different type of building than before. In any event, under the influence of Chinese craftsmen, many buildings55 were constructed in this way. Although examples from this period are not to be found nowadays, we are certain that their form would have resembled those still found in some more remote parts of the towns on Taipa and especially on Coloane. There are several reasons for this: 1) Through the centuries, Chinese architectural features have been retained an extraordinarily similar form, with only small variations in decorative detail; 2) although built during the 19th and early 20th century, the buildings in these towns, which are generally rooted in Chinese forms, demonstrate a symbiosis with European details - such as the use of friezes on the entablature, frames around the windows and doors, drip-catchers in the arches, small columns in the corners of doors, and small pedestals on the outer walls - which give them a Sino-European touch; 3) these details, which are a clear adaptation of very much earlier forms, originate from the reinterpretation of mediaeval knowledge. We have, consequently, a basic type of architectural form whose appearance is in accordance with the popular tradition of Chinese construction. In other words, they are similar to the buildings that must have existed in the period in question, insofar as they make use of a language adapted from "other" kinds of knowledge.

Generally rectangular in plan, the buildings were arranged in such a way as to retain, as far as possible, an inner open space - the courtyard - with the various rooms of the house opening off it. Although relatively small, this courtyard ensured ventilation and sunlight inside the dwelling, and was a permanent feature of the Chinese courtyard-house, as we have described previously. In their spatial arrangement, volumetric structure and materials, the buildings always demonstrated a preoccupation with climatic conditions. Therefore they attempted to accentuate currents of air by their positioning in relation to prevailing winds, ensuring a through-draught by the way in which doors and windows were arranged. Another characteristic, certainly adapted from Chinese typology, was that the side walls jutted out the wall of the façade, thereby offering protection from the direct action of the strong winds, while still enabling ventilation; sometimes, the finishing of the roof over the eaves (consisting of tiles laid directly on the structural beams) was a way of accentuating the eddying of vertical winds, together with the use of the walls of the opposite buildings (see Figures 20 and 20A). The tiles followed the ren zi pitched system, and ceramic glass tiles, were the most common as already described.

It is interesting to note that, in terms of the arrangement of buildings in relation to climatic features, the structure of the settlements in Taipa and Coloane were in the same north-east - south-west direction as those in Macao, signifying that this was the most rational arrangement in view of those features (see Figure 17).

The "Rua Direita" and secondary roads on an early 20th century map of Macao. (Fig. 17)

Returning to Macao, the natural axis that Rua Central described was the defining line between two parts of the city: the Portuguese were moving towards the eastern part, the Praia Grande area, which provided a good, large port (outside the typhoon season); and the Chinese established themselves in the western part. At the same time, another Chinese village began to grow along the banks of the Patane, which was particularly welcoming to visitors from faraway lands who wanted to trade with the Portuguese but whose lack of trust prevented them from forging the close friendships with these foreigners that would enable these newcomers to co-exist in the same city. We shall see how these differences became clearly marked during the city's growth, which was confined of necessity within the city walls, because of the need for defence against external threats.

Certainty in the future

Having a guarantee of stability, the Portuguese felt they had the courage to build a city as they had done in the past. This period was also "the age of the churches" during which Macao's main houses of worship were built.

Because of the increasing difficulty caused by the Portuguese dependence on the provision of building materials by the Chinese, in particular the black clay bricks used in the region, it was necessary to have recourse to an old Portuguese skill in that field: lath and plaster walls. This method had a long tradition in Portugal and was used successfully in Malacca and the first trading-posts China (Liam Po and Chin Chew). Lath-and-plaster walls were very strong, although they took longer to build because of the earth compaction required as well as the corresponding increase in wall thickness. However, the material turned out to be an excellent thermal insulator, enabling interiors to remain extremely cool. However, once again, knowledge of other materials used locally brought about an improvement in the consolidation of lath and plaster and therefore a reduction in compaction time as well. This other material was oyster lime, a product derived from burned oyster shells, and it became the aggregating agent in the structure of lath and plaster. Straw was also used at that time as an inert substance, forming an extraordinarily strong cohesive unit called chunambo. This material was chosen for the building of city walls and for the construction of the churches that were to follow, supported by the use of stone for the façades.

Images of gods on the doorway protecting the home. (Fig. 18)

As had been the case in the previous trading-posts, a need was felt to build a palisade that would provide the necessary protection from external elements and consolidate the city. But in this case, a city wall was not merely a precaution against military attacks; it was also protection against the constant interference by the Chinese authorities in the development of the Portuguese community. The Chinese always had a grave mistrust of foreign settlements, which, in the case of Macao, was accentuated by the speed at which the city appeared to be growing, both physically and economically. Had imperial consent not been granted, it is certain that widespread xenophobia would have been stronger than the special commercial interests of a few mandarin families, and would doubtless have culminated in another expulsion. We sense this in reading in the Monografia de Macau: "Meanwhile, with the withdrawal of the Japanese, the foreigners continued to remain. Some said that they should be exterminated, others that they should be transported to the high seas of Long Pak, and commercial transactions carried out in the ships56". A fact confirming the aforementioned interference is another quotation from the previous work, which seeks to define a way of actually structuring the settlement: "Because the ministers decided to proceed in accordance with this line of thinking, the post of lieutenant was created, stationed at the Leong Mak camp with a detachment of 100 men for its defence. A request was also made that the foreigners should be ordered to cluster together their huts along the middle of the main street and surround them on all four sides with trees and high palisades and, in order to show respect for the majesty and virtue of the emperor, they were divided into left-hand and right-hand groups, and the number of inhabitants of each was fixed. 57" For these reasons, the need to build a primary palisade, as we have already stated, was emphasised and ordered by Tristão Vaz da Veiga, Commander-in-Chief of the first Macao-Nagasaki voyage. This did not please the Chinese, but it was approved because it could be justified by the need for protection against Japanese pirates. The first wall to protect Macao was built of large tree trunks, a repetition of what had been done in Malacca. The city area was well defined by this enclosure which also served to separate the Portuguese area from the Chinese camps to the north. The wall also contained sections reinforced with lath and plaster, for greater durability, and although Tristão Vaz wanted the surrounding wall to be as short as possible so it could be more quickly built, it could not be less than four hundred fathoms (800 metres) long, for two reasons: first, because of a hill that had to be inside the walls (possibly corresponding to the present day Jardim Camões), and second, because the settlement was expanding rapidly. Two hundred and seventy fathoms (596.2 m) of wall were built together with four square bastions (the urgency of the situation prevented them from being constructed in any other way.) The walls measured 14 and 15 palms high (3.08 m and 3.30 m) and were 6 palms (1.32 m) thick at the base and 5.5 palms (1.21 m) thick at the top. Rich and poor alike, large and small families, Christians, Chinese and Jesuits undertook the construction work. Lath and plaster walls were improvised with planks pulled out of the doors of houses. In sixteen days, 271 fathoms had been built (17 fathoms/day). The plan had been for 271 fathoms (596.2 m) on the land side and 129 fathoms (283.8 m) on the sea side, where there was a quay at each resident's door. Tristão Vaz believed that these latter should be constructed so as to double as a wall as well.

However, it was only in 1622 that this first wall was replaced by a stronger wall58 of stone blocks, supported by some strategically placed forts which were also built at the same time (the Monte Fortress, the São João Fort and the São Francisco Fort to the north; to the south, by another stretch of wall, the fort supported by the Penha chapel, the Bomparto Fort, and later the São Tiago da Barra Fort). The wall as a whole still followed the mediaeval system of military construction, including its traditional towers as already seen in Goa and Malacca, for which the design typology was retained.

This was the basic concept of the mediaeval city, built inside the walls. "These cities, perfectly defined by their surrounding walls - which played the same role as a frame in a work of art - with their buildings well -proportioned and presided over by the dominant feature of the cathedral or castle, always have a delightful effect, when not despoiled, modified or demolished by the massive growth of recent times. The mediaeval city is a homogeneous medium and at the same time is entirely identifiable in all its parts. There is nothing discordant in it nor anything that could rupture its subtle texture; nevertheless, no street can be mistaken for another, no square either large or small is without its separate identity, each building speaks its own language, perfectly hierarchised by its meaning and symbolic value, submitting to the great representative monuments that are dominant in volume, scale and excellence" 59. This passage from Goitia helps us to think about the city of Macao, which was without doubt a late example in the Far East of the old western city. And if we compare this type of mediaeval city with Chinese ones of the same kind, we find a similarity of intention: intramural development with a sense of protection, defence, definition of the urban limits and separation from the agricultural zone. In some ways we can say that the Chinese city shares the philosophy of the European mediaeval city.

Rua da Felicidade, a street in Macao's Chinatown. In "Um Marinheiro em Macau. 1903 - Album de Viagem" (A Sailor in Macao, 1903 - Album of a voyage), by Filipe Emílio de Paiva. Macao Maritime Museum. (Fig. 19)

There was little Portuguese settlement before 1568, as confirmed by Dom Melchior Carneiro in 1575 when he remarked: "When I arrived there were very few houses belonging to Portuguese and there were also some Christians from that territory..."60.But it was after that date that population growth paralleled that of the city, coinciding with the arrival of the priest, 61 the Bishop of Niceia, who was also responsible for the creation of the Senado (Senate House) in 158362. A man of great initiative, the Bishop opened a hospital, which was later known as São Rafael63,within a year of his arrival; a friary, the Misericórdia, 64 soon followed. At the same time, a leprosarium was built in São Lázaro. Seven years after his arrival, he wrote that the population had increased and the city could be considered medium-sized, justifying the creation of the Diocese of Macao by Pope Gregory XII on the 23rd of January 1576. In 1578, according to information provided by Father Mattei Lopez on the 29th of November that year65, the city already had ten thousand inhabitants and "five churches in which Mass was said every day"66. These churches were Santo António, Madre de Deus, Sé (the Cathedral)67, São Lourenço68, and, outside the palisade, the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Esperança (later known as São Lázaro, as it was close to the leprosarium)69.Little is known of the early architectural features of these churches, which were ruined due to adverse weather conditions and the lack of durability of the first materials used; destroyed by fire or simply by the intention of achieving greater glorification which led to the construction of more majestic churches on the sites of the original ones. We know that the orientation of the Sé was different from that of the present day church (at that time it was positioned in a northeast - southwest direction, exactly perpendicular to the present one) and we also know, from existing illustrations of Macao, that all the churches had large churchyards in front of them, which created different urban nuclei, equivalent to the corresponding parishes and districts (see Figure 11). The organisation of the city was based around the religious buildings that were located along the main street. Thus the stamp of medievalism which characterized the morphology and development of Portuguese cities as well as of the cities discussed above, became more apparent in Macao: the Rua Direita spontareously provided a link between the churches - and the churchyards that were their points of reference - and the most important civic buildings.

As the city expanded towards the south, the eastern district remained unoccupied. It was the ideal area for the Franciscans - who had arrived in the peninsula in 1579 - to set up house. Welcomed by Dom Melchior, Pedro de Alfaro and João Baptista Lucarelli, both Spaniards, they inaugurated the Convento de Nossa Senhora dos Anjos (later renamed São Francisco) on the 2nd of February 1580. The Franciscan design for the construction of their church and monastery was the same as that which they had used in Europe: removed from the city centre, situated in a relatively high place, close to water, in a spirit of living with nature and celebrating its relationship to heaven, according to the teachings of their master and founder, St. Francis of Assisi70.

By 1581, Macao already had around two thousand inhabitants71 with five hundred houses spread around the Christian city, now in a more regular form. However, constant control by the mandarins was still apparent, and in 1583 a decree from the Governor General of the Province of Canton created the "Five prohibitive orders" prescribed for the inhabitants of Macao. Point 5 stated: "Further construction work is forbidden. The inhabitants of Macao have built sufficient houses for their habitation. Therefore, if any are destroyed they will be permitted to be rebuilt as they were. But if anyone should dare to construct buildings on a mere whim, to add single stone to the wall, or undertake any extra works, the building will be destroyed, the timbers burned and the perpetrator severely punished."72 These orders were repeated and extended to churches, with extra stipulations73 added in 1749, when a metal plaque was put up in Mong Ha in the Tribunal do Mandarim (Mandarin's Court) and a Portuguese translation was lodged in the Senado, which clearly demonstrates that by the 17th century the city had acquired such a degree of economic power that it had ignored those first rules imposed by the Chinese and had expanded vastly in that golden age of oriental trading. Even after a few lean years, such as those that resulted from the 1634 prohibition of the Philippines route, the 1639 prohibition of trading in Canton, the end of dealings with the Japanese in the same year (and its tragic confirmation with the martyred embassy in 1640), and the 1641 fall of Malacca to the Dutch, the trading alternatives that the persevering Portuguese discovered in IndoChina, Macassar and Timor enabled them to maintain a high standard of living in Macao and to continue the city's expansion.

In 1586 Macao achieved the definitive status of city and became known as the City of the Holy Name of God of Macao in China. A democratic government was established in the form of a Municipal Administration whose officials were elected by the citizens. These officials then began to exert control, at another level, over construction in the city, including the specification of the type of building materials to be used and their respective quality control. This latter implied a guaranteed resistance to fire as this was the main cause of the great tragedies that befell Macao. However, it was only at the end of the first quarter of the next century that proper inspection procedures for building materials were introduced.

The Dominicans also founded a community in Macao. In 1587 three priests arrived on the peninsula - António de Arcediano, Alonso Delgado and Bartolomeu Lopes - following a difficult voyage from Mexico along the Acapulco route (the Silver Route). They settled down, with the aid of the Provisor of the Bishopric, in some timber houses situated in the very centre of the city, entirely suited to their mission to preach and their requirements for survival, being a mendicant order. Their calling was to preach in the streets, so they always built their monasteries in the centre of villages in order to avail themselves of charity from the inhabitants - who, in Macao, guaranteed them substantial donations. Their quarters soon became a fine church made of lath and plaster, bearing the name of Santa Maria do Rosário.

Up to 1590 the city had spread southwards, along the natural axis mentioned several times previously, facing the Praia Grande, the new port favoured by the Portuguese. In expanding southwards, they encountered Penha Hill which blocked their path at the furthest point of the peninsula. The main aim was to build near the port, but this intention was also restricted by the base of Penha; therefore major urban development from then on naturally took place around the São Lourenço Church, oriented towards the south east, towards the bay formed by the beach (see Figure 14). The price of land then began to rise, as the peninsula was occupied by people who had come from outside to seek their fortune in this city of wealth. This was described by Father Álvaro Semedo when he wrote: "They (the Portuguese in Macao) immediately began to build, each occupying the place and the site he wanted, but the land they had taken that had had no value came to be worth a great deal of money, so much so that it was not easy to believe the price of any piece of buildable land in the city, because in the absence of India, this city keeps growing and becoming wealthier..."74

Street corridor accentuating air currents (whirlwind effect enhanced by the architectural structures). (Fig. 20)

Detail of the eaves on a building in the town of Coloane (Fig. 20A)