In reply to the question:

—"Does God love the English?", which had been deliberately asked to confuse her, Joan of Arc answered:

—"He loves the English when they are in their own country."

"Many of the missionaries visited the embassy. One of them, a mild-mannered and courteous Portuguese citizen, was simultaneously appointed by the emperor to act as the leader of the Europeans at the Bureau of Mathematics and by the Pope, at the recommendation of the Queen of Portugal, to serve as Bishop of Peking [Beijing]."1

This brief reference to Fri[Father] Alexandre de Gouveia (° 1715-† 1808) was made by Sir George Staunton in his famous work, An Authentic Account of an Embassy To The Emperor of China undertaken by order of the True King of Great Britain [...], published in London in 1797.

John Barrow, another of those who accompanied Lord Macartney's embassy to China, devotes a few pages of his Travels in China to the subject of Fr. Alexandre de Gouveia and the work of the European missionaries in Beijing. • The characterization of Fr. Alexandre is almost a replica of Stauntonís words:

"The priest was a mild-mannered and serene man, with pleasant manners and a simple and modest behaviour."2

Alexandre de Gouveia was born in Evora in 1715.

The protégé of Fr. Manuel do Cenáculo, the Bishop of Beja and a man of influence at the Portuguese court, Fr. Alexandre was a young man from the Alentejo province who became a Franciscan friar. He was the first graduate in Mathematics from Coimbra University, after the reforms introduced by the Marquis of Pombal in 1772.

It was while he was still a teacher of Philosophy and Mathematics at the Convento de Jesus (Convent of Jesus) in Lisbon that he was appointed Bishop of Beijing in 1782. At that time, Beijing was a remote Diocese of the Chinese Empire that had been founded in 1690 and was still dependent upon the Portuguese Padroado of the Orient.

The court of Lisbon decided to plan Fr. Alexandre's journey in great detail and gave him a series of important tasks to perform. He was to be the ambassador and defender of the interests of both Portugal and Macao at the Chinese Court. These were the Instrucções para o Bispo de Peking (Instructions for the Bishop of Beijing), published in 1942, by the Agência Geral das Colónias, under the guidance of Manuel Múrias.

Since the Court of Lisbon was ignorant of almost everything to do with the world of China, the principles by which it was governed, the politics, bureaucracy and general sensitivities of the Chinese, the Court of Lisbon had entrusted Fr. Alexandre with an impossible mission, especially with regard to the task of defending the rights that had supposedly been acquired by the Portuguese in Macao. It was further suggested to him that, in addition to being the Bishop of Beijing, he should also act as Portugal's permanent ambassador in the Middle Kingdom. 3

Ten years after the Portuguese Instrucções had been given to Fr. Alexandre, the British ambassador Lord Macartney — who was similarly uninformed about Chinese affairs — arrived in Beijing with a completely unrealistic proposal and series of demands, one of which was that Britain should also have a resident ambassador in the Chinese capital.

On his arrival in Beijing, in January 1785, Fr. Alexandre was confronted with an immense country, governed by very different laws from those of the Western Catholic world, where being a foreigner represented as stigma that it was impossible to overcome and where even the air that he breathed was different. The Bishop also found there four Portuguese ex-Jesuits, the priests Jos de Espinha (°1722-†1788), Inâcio Francisco (°1725-†1792), André Rodrigues (° 1729-†1796) and José Bernardo de Almeida (°1728-†1805).

José Bernardo de Almeida and the French priest Louis Poirot (° 1735-†1813) were the two interpreters chosen by the Emperor to accompany Lord Macartney's embassy during its stay in Beijing and Chengde• (Jehol•) in 1793. Bernardo de Almeida made his own personal contribution to the failure of the British embassy, as we shall see later on.

Almost two years after his arrival in Beijing, Fr. Alexandre de Gouveia informed Martinho de Melo e Castro, the Minister and Secretary of State, that he was unable to fulfill the Instruções that he had been given in Lisbon. He wrote in a letter from Beijing, dated the 3rd of November 1786:

Audience of the emperor.

Unknown Chinese artist. Late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

Watercolour on paper. 49.5 cm x 37.4 cm.

In: PESSOA, António Sérgio, annot., Pinturas da China Trade II, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1990, ill. 24 [a collection of postcards].

Audience of the emperor.

Unknown Chinese artist. Late eighteenth or early nineteenth century.

Watercolour on paper. 49.5 cm x 37.4 cm.

In: PESSOA, António Sérgio, annot., Pinturas da China Trade II, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1990, ill. 24 [a collection of postcards].

"The customs of the Chinese are similar to their laws. Failure to perform a small formality authorized by custom is a crime that is punishable by the withdrawal of the mandarinate; violation of a small point of law is a fault that is punishable by exile fore life and sometimes by death. The present Emperor [Qianlong], a prince of extraordinary talent and who alone governs an immense population, has so intimidated this nation, itself made even more timid by its own nature and by the strict observance of laws and customs, that the mandarins tremble in his presence and even the ministers of state never suggest to him any business which they think may displease him, fearing their own ruin at the slightest blemish in their work.

In case of foreigners, the policy is even stricter. No foreign ambassador or minister is allowed here except for the brief period of time during which the business relating to that embassy is conducted. [...] European missionaries, who have been accepted here as servants of the empire in mathematics and the arts of painting and watch making, have often been in danger of being expelled on the merest suspicion by the Chinese that they nurture intentions other than that of preaching Christ's law."4

Since the middle of the eighteenth century, Britain had dreamt of possessing a permanent basis on Chinese territory. Trade in Guangzhou was growing and the tea imports and opium trade, originating from India, were beginning to provide sizeable profits for those British adventurers who were prepared to risk their ships in journeys to the Far East and for the countrymen of the East India Company. India had become the jewel in the British Crown and China, with all its different kinds of wealth and riches, or at least some ports on the Chinese coast were falling into the sphere of a much desired British dependency. Britain coveted Macao. 5

In his book, Immovable Empire, Alain Peyrefitte speaks of a meeting in Macao with the priest Manuel Teixeira,"[...] the most erudite of Portuguese historians [...]", and goes on to say:

"The British are essentially lazy. The small country Portugal had been established in Macao for two hundred and fifty years: they either had to find another Macao or else take possession of our own. Macartney undertook a meticulous survey of the Portuguese defenses. The missionaries could not avoid noticing his manoevers! With the Chinese, it is always possible for us to understand one another. With the British, there is nothing to be done. [And the French historian and diplomat concludes, thus:] What a strange paradox!"6

Were the British designs upon Macao at the time of Lord Macartney's embassy so strange after all? How could anyone fail to understand the natural Portuguese hostility towards the British presence in the China seas? Were both Macao and the Portuguese presence in the Middle Kingdom in danger or were they not? Later events, such as the failed British attempts to occupy Macao in 1802 and 1808 prove that all the fears of the Portuguese were fully justified?

On the 22nd of December 1792, at a time when Lord Macartney's British embassy was still on its way to China, where it was to arrive only in June 1793, the then governor of Macao, Vasco Luís Carneiro de Sousa e Faro wrote to the Court of Lisbon:

"Once again the British are sending an ambassador to China. Lord Mecartin [sic]has already been appointed to set sail in a warship bound for Beijing, with another two frigates in consort, only shortly after its customary fleet has been sent to Guangzhou, where here are already 17 vessels, voyaging in one of these ships three counselors who will take up residence there, entrusted with the special task of conducting political business relating to the embassy in order to resolve in this private counsel such matters as may arise in this respect.

It is public knowledge that the purpose of this embassy is that the aforesaid British want the island of Guangzhou so that they might settle there and when they achieve this, which I do no doubt they will, as we do no have in that Court anyone who might impede such a plan, no small damage will be caused by this proximity to Macao, at least if we do not guard against the future."7

I wish to draw attention to the statement by the then Governor of Macao that"[...] we do not have in that court [Beijing] anyone who might impede such a plan [...]." As it happens, there were at that time in Beijing at least three men who were ready to impede the British plan and had he power to do so. These were the priests José Bernardo de Almeida, André Rodrigues and the Bp. Alexandre de Gouveia.

José Bernardo de Almeida, who had the Chinese name So Dezhao, • was an elderly ex-Jesuit and had been in Beijing since 1759. Thirty-four years of living in the Chinese capital had inevitably caused him to acquire Chinese ways and manners. He held the important post of director of the Bureau of Mathematics and Astronomy (not in fact"presidente"("Chairman") as European missionaries were in the habit of calling themselves, since these two chairmanships were always awarded to two Manchu nobles). Almeida was a surgeon and the personal physician of He Shen;• the 'colao'• Ho, a kind of Prime Minister, the favourite and lover of the Emperor Qianlong.•After the Emperor, He Shen was the most powerful man in China. The Minister played a fundamental role in ensuring the failure of Lord Marcartney's embassy. Permanently by his side was José Bernardo de Almeida.

In 1774, the French priest Louis Amiot, one of the most brilliant Jesuits missionaries ever to visit China wrote: "Because of the services which he renders, a surgeon may obtain more protectors for our Holy Religion than all the other missionaries with all their talents put together!"8

José Bernardo de Almeida knew better than anyone else at the Court of Beijing how to obtain protectors for the Portuguese religion and the direct interests of the Portuguese missionaries. The biography of this fabulous man, who enjoyed such a fascinating career in the great and intricate labyrinth of the Chinese Court, has yet to be written. 9

Fr. André Rodrigues, who was also an ex-Jesuit and was given the Chinese name of An Guoning,• had arrived in Beijing in 1759, with José Bernardo de Almeida. He was a director of the Bureau of Mathematics and Astronomy and enjoyed a very good relationship with the Chinese mandarins. The hao guangxi• were just as highly regarded in the past as they are today.

The Bishop of Beijing, Fr. Alexandre de Gouveia, whose Chinese name was Tang Shixuan,• also held the position of deputy director of the Bureau of Mathematics since 1787 and had cleverly succeeded in gaining the good graces of the mandarins at the Chinese court and, most importantly, he regularly supplied them with "tabaco de Amostrinha" (snuff, and perhaps opium?), which he received as a special privilege from Macao and India. Fr. Alexandre was also responsible for administering the valuable assets of the diocese. He had grown used or perhaps forced to become used to bestowing magnificent gifts upon almost all mandarins or officers of the Chinese court who dealt directly with the Portuguese at the two churches of Nantang• or the Immaculate Conception (where the Bishop himself resided) and Dongtang• or Saint Joseph. 10

At the orders of the Emperor, Almeida, Rodrigues and Gouveia were to examine the astronomical instruments which Lord Macartney brought with him as a gift, and of course never failed to take every opportunity to plot and stir up hatred against the British, as we shall soon see.

In June 1793, another missionary was to enter upon the scene with entirely opposite aims.

The French ex-Jesuit Jean-Baptiste Grammont (° 1736-†1812?) had arrived in China in 1770 to serve as the court musician. He had witnessed the extinction of the Society of Jesus, the main divisions within it, the plotting and silences of the European priests in Beijing, and had lived in Guangzhou between 1785 and 1791. These six years of contact with people, particularly the British, who traded in the great city of the Pearl River, had turned Grammont into a servile friend, dedicated to the defense of the British interests.

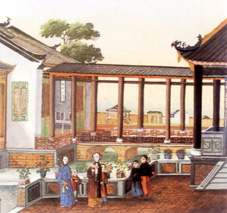

Palace with ladies and children.

Unknown artist. Late eighteenth or early ninteenth century.

Watercolour on paper. 49.6 cm x 37.7 cm.

In: PESSOA, António Sérgio, annot., Pinturas da China Trade II, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1990, ill. 19 [a collection of postcards].

Palace with ladies and children.

Unknown artist. Late eighteenth or early ninteenth century.

Watercolour on paper. 49.6 cm x 37.7 cm.

In: PESSOA, António Sérgio, annot., Pinturas da China Trade II, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1990, ill. 19 [a collection of postcards].

Shortly after his arrival on Beijing, Lord Macartney received two letters from Fr. Grammont delivered secretly by a Chinese envoy. The French ex-Jesuit pledged his unconditional support to the British ambassador and advised him to take great precautions against Br. José Bernardo de Almeida, the official interpreter of the embassy and a close friend of the Prime Minister He Shen and the Emperor. Grammont said that Almeida was capable of doing almost anything to ensure the failure of the British mission: 'If your Excellency wishes to tell the leading mandarin who will accompany you that you wish to have me in your retinue, whether as an interpreter or performing any other role which you may consider appropriate, and, at the same time, to inform the Emperor of this fact, then I am certain that all of the credit enjoyed by this missionary [José Bernardo de Almeida] will be eroded, that I shall at least have the possibility of opposing him and that I shall be able to destroy all these disadvantageous proposals suggested in some of the letters coming from Guangzhou and Macao, which are nothing but hotbeds of envy and malice.'11

Throughout Lord Macartney stay in Beijing, Grammont's unhealthy obsession and anger with Bernardo de Almeida and the Portuguese grew even stronger. But everything went badly for the French priest. Both the Chinese and the British overlooked him altogether. The interpreters and astronomers in the service of the Emperor of China, José Bernardo de Almeida and André Rodrigues, were promoted to transparent blue rank — three officials, grade three mandarins, which was almost at the very top of the hierarchy of the 'mandarinate'. The other interpreters, the French priest Poirot and the Italian priests Panzi and Adeodato, rose to opaque white rank — six officials, 'white glass' mandarins. Fr. Alexandre had been made a rank-six offcial since 1787. 12

On the 30th of August 1793, Fr. Grammont informed Lord Macartney: 'It is convenient that Your Excellency should know your friends. The Portuguese Almeida arrived in Beijing with the title of surgeon. There being no other Portuguese representative, he became a member of the Bureau of Mathematics and Astronomy, of those most rudimentary principles he is in complete ignorance. His talents as a surgeon have provided him with various acquaintances amongst the most important figures. Three months ago he had the good fortune to cure He Shen, the very powerful minister at the court, of a slight indisposition. Such is the origin of his fortune and this is why he had dared to wish to have the honour of being your interpreter. Fortune and honour that he will soon lose if Your Excellency manages to prevent him from being your interpreter at Jehol. [...] I further beseech Your Excellency to believe that it is not out of hatred or spite that I speak thus of this missionary. Everybody here knows that we have always been linked by the closest bonds of friendship. But the duties of friendship have their limits and are not at odds with the duties of justice.'

In the same letter, Grammont advises Lord Macartney to present valuable gifts to the Emperor's children and to the leading figures in the Court, concluding thus: 'It is absolutely essential that Bernardo de Almeida should not become in any way involved in the distribution or presentation of these gifts, because this will provide him with the best opportunity of increasing his worth and repeating his dishonourable intentions. And I also wish to warn Your Excellency that Messrs. Poirot and Raux [the head Lazarist of the French mission] n 'ont pas assez díusage du monde et sourtout du monde de ce pays-ci (are not used to the life of society, especially the society that exists here).'13

Who then was more accustomed to successful survival in such a society? José Bernardo de Almeida and his friend, the Bp. Alexandre de Gouveia.

Lord Macartney took the warnings of Fr. Grammont seriously. On his first meeting with José Bernardo de Almeida," [...] the ambassador was convinced of the accuracy of the picture that had been painted of him. A bad man, envious of all Europeans, except those from his own country."14

Not at all distressed by the cold reception which he felt had been given by the British ambassador, José Bernardo de Almeida continued to be the shadow of 'colao' Ho, the Prime Minister He Shen. The old Emperor Qianlong was at his summer residence in Jehol, two hundred kilometres from the capital and it was only when Lord Macartney visited him there that he learned of the British intentions. Frs. Almeida and Poirot were already in Jehol where they acted as interpreters, and much else besides.

Britain's claims on Chinese territory were absolutely inconceivable in the eyes of the Chinese and represented an insult to the old empire, the centre of the world,.

Here is a brief summary of the British proposals:

1. To allow the British merchants to trade at the ports of Zhousan,· Ningbo· and Tianjin; ·

2. To allow them to have a permanent establishment in Beijing to deal with British affairs;

3. To allow them a small area of land on the island of Zhousan, or in the neighborhood, as a store for their goods and residence;

4. To allow them a similar privilege in Guangzhou;

5. To abolish the transit duties between Macao and Guangzhou, or at least to reduce them to the standard of 1782; and

6. To prohibit the exaction of any duties, other than those stipulated by Imperial Decrees. 15

Such requests, which were handed to the Chinese on the 3rd of October 1793, received an immediate answer. On the 7th of October all the points in Lord Macartney's proposal, which had been presented on behalf of King George III, were rejected and orders were given for the embassy to leave Beijing and return to its own country. This was the supreme humiliation for the British, who would have to wait another fifty years to be able, in their turn, to humiliate the Chinese in the course of the Opium War (1839-1842) and finally gain the territory near Guangzhou which they had coveted since 1793. Only that this territory was not to be Macao, but the island of Victoria, or, in other words, Hong Kong.

Two years after Lord Macartney's departure Van Braam, who was the agent responsible for the Dutch business in Guangzhou and served unsuccessfully in 1795 as the Dutch ambassador to China, discovered that even the most valuable of all the gifts that Lord Macartney had offered to the Emperor had been prejudicial to the British interests. "The missionaries [André Rodrigues, Alexandre de Gouveia, and others] noted that the various mechanisms of the superb planetarium were worn and that the inscriptions on the various parts were in German. They informed the Prime Minister [He Shen] of these facts and he, already shocked by many features of the British embassy, made a report for the Emperor informing him that the British were nothing but crafty impostors. The Emperor was indignant and ordered the British embassy to leave Beijing within twenty-four hours."16

By 1795, Fr. Grammont had not forgotten Lord Macartney and the failures of his recent mission. Nor had he forgotten the Portuguese or Fr. José Bernardo de Almeida, his fellow missionary, an ex-Jesuit like himself, to who he was forever linked by the “[...] closest bonds of friendship.” Grammont wrote a letter to the Dutch ambassador in Guangzhou. Essentially the intentions of the French priest were no different from those which had first led him to write to Lord Macartney. He was now willing top place himself at the service of an envoy of the Dutch government, intending to gain for himself the dividend of a successful mission from a powerful European country and to 'stand up' José Bernardo de Almeida. But once again everything went wrong. The Dutch ambassador did not even gain any credentials from the Chinese court, who dismissed him summarily. The letter that Grammont wrote to Van Braam is, however, of great importance and I should now like to transcribe it almost in its entirety:

"Like all foreigners who do not know China excepts from books, these gentlemen [the British] were not familiar with the ways, customs and etiquette of the Court. They did not succeeded in having with then a European missionary who might have given them instructions and guidance.

Thus:

First: They did not bring any gifts for the Minister of State [He Shen], nor for the Emperor's children.

Second: They refused to perform the customary ceremony of greeting the Emperor, without giving any explanation for such refusal.

Third: They presented themselves dressed in clothes that were much too simple and common.

Fourth: They did not take the precaution of graisser la patte (greasing the palms) of the different people appointed to supervise the affairs of the embassy.

Fifth: Their requests were not made in the tone or in the style appropriate to the country.

Another reason for their failure, and in my opinion the main one, was the intriguing of a certain missionary [Almeida], who, imagining that this embassy might be prejudicial to the interests of his own country, continued to arouse feelings that were unfavourable to the British nation.

Furthermore, the Emperor is old, there is intrigue everywhere, machinations, such as there are in all countries. Besides, all the important figures, the Emperor's favourites, are people who are avid to receive gifts and riches."17

Nine years after Lord Macartney's unsuccessful embassy a British fleet was to be found stationed in front of Macao and preparing to disembark and occupy the small city. In panic, the Senate of Macao requested the help of the Portuguese priests who were close to the Chinese Court. Once more, Fr. José Bernardo de Almeida and Bp. Alexandre de Gouveia entered into direct conversation with the leading figures of the Empire.

Together they drew up an extensive Memorial, dated the 19th of August 1802, addressed to the "[...] Prime Minister of state [...]" in which, amongst many other questions, they spoke of 1793 and Lord Macartney's embassy.

In 1966, in a commentary on this Memorial which he published and translated from Qing Jiajingchao waijiao shiliao· (Diplomatic Documents from the Reign of the Emperor Jiajing), Beijing 1932, Lo Shu-fu· states as follows: "This Memorial shows that during Macartney's mission, the Portuguese priests at Court did secretly undermine British interests by deliberately instilling the fear that Britain had annexed territory everywhere and would do the same with China."18

What does the memorial of these two Portuguese priests in fact say?

"We, So Dezhao [José Bernardo de Almeida] and Tang Shixuan [Alexandre de Gouveia], and other Portuguese companions, state with all due respect that we have voluntarily exiled ourselves from our own country, many leagues distant from this Empire, in order to place ourselves at the services of the magnificent Emperor of China, from whom, in the course of our residence at this Court for so many years, we have received great and repeated benefits, for each of which we cannot worthily show our gratitude, notwithstanding all the diligence with which we endeavour to show our recognition through the limited services that Your Majesty has entrusted to our care.

We recently received a letter from our compatriot, the attorney of the city of Macao, who resides thereat, in which he gives us to understand that the city is currently involved in a most arduous negotiation, which may result in consequences that are not only of the greatest import for its residents, but also extremely pernicious for the very monarchy of China.

It is well known that the Portuguese residents of Macao have been overwhelmed with the infinite favours bestowed upon them by the magnificent emperors of the present dynasty of China, in the observance of those laws and ordinances they have long enjoyed supreme tranquillity and peace.

Amongst the various Western nations, however, that come from outside regions to trade with China, there is one kingdom known as England [Great Britain] whose people have the distinctive character of being deceptive and insincere. For several decades now, this nation has proposed and continues to harbour the ambitious design of absorbing into it all that there is, for which purpose it frequently makes use of the apparent and feigned pretext of trade, with which it conceals its occult and deceitful instincts. The fame, kindness and protection of the Chinese monarchy, which with its virtue, wisdom and power supports and defends its subjects, has so far prevented the English from revealing their sly projects.

In the year 58 of Emperor Qianlong's reign [1793], they sent a huge ship with presents to the emperor and, amongst many things for which the English deceitfully asked, their requests were designed not only to improve their trading relations but they also asked that they should be given an adjacent island, all with the aim of being able to carry out their premeditated designs. Yet, as the great predecessor of the present Emperor [now Jiajing] fortunately understood their ploys and did not assent to their deceitful wishes, they went away. However, notwithstanding their not having succeeded in the purposes for which they had come, they nonetheless have not relinquished their clams, no have they lost sight of any opportunity of achieving their designs. [...]

Previously, having gained entry to a kingdom in India known as Bengal on the pretext of trading, they ended by extinguishing it. First they requested in the kingdom a small place for their interim residence, thereafter introducing many people and warships, and swallowed up this kingdom which is adjacent to Tibet, as may be known in China. This is not the only area in which the English have made use of some stratagems sand if they manage to achieve their ends in China, peace and quiet will not last long in this empire. The Portuguese, however, have existed in this Empire for more than two centuries without so far having given the Emperors no cause for feelings of distrust or disquiet. [...]

For the benefit of this protection that we hope to achieve, we are eternally grateful.

It is with due veneration that we, So Dezhao, Tang Shixuan and companions, have the honour to address this petition to your Excelencies."19**

* MA by the University of Lisbon. Former lecturer of Portuguese at the Department of Foreign Languages of the University of Beijing.

NOTES

** Revised version of the paper: ABREU, António Graça d', Dom Frei Alexandre de Gouveia, Bishop of Peking, and Lord Macarteney's Embassy (1793), in ELEVENTH CONFERENCE OF THE EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION OF CHINESE STUDIES, Barcelona, Pompeu Fabra University, 4-7 September 1996 — [Oral communication...].

1 STAUNTON, George, An Authentic Account of an Embassy to the Emperor of China undertaken by order of the king of Great Britain; including the Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants; and preceeded by an account of the cause of the Embassy voyage and voyage to China [...], 2 vols., 2 vols., London, John Stockdale, 1797, vol. l, p.233.

2 BARROW, John, Travels in China, London, 1804, p. 111.

3 GUIMARÃES, Ângela, ed., Uma Relação Especial: Macau e as Relações Luso-Chinesas (1780-1840), Lisboa, Ed. Cies, 1966, p.49 — For a brief summary of these Instrucções and the appropriate commentary by the editor.

4 AHU: Caixa [box] 15, doc.46, Carta de Alexandre de Gouveia, em Beijing, a Martinho de Melo e Castro, em Lisboa, 3 de Novembro 1786.

5 COATES, Austin, Macao and the British: 1637-1842: Prelude to Hongkong, Hong Kong - Oxford - New York - et al, Oxford University Press, 1988, p.78 foll.

6 PEYREFITTE, Alain, O Império Imóvel, Lisboa, Gradiva, 1995, p.12 [The Portuguese edition of the French original].

7 AHU: Macau, Caixa [box] 19, doc.36, Vasco Luís Carneiro de Sousa e Faro, em Macau, para a Corte [de Portugal], em Lisboa, 22 de Dezembro 1972.

8 Apud PEYREFITTE, Alain, op. cit., p.317 — For an unpublished letter from Fr. Amiot to the Minister Bértin, dated September 1774.

9 AHU: Macau, Caixas [boxes] 8-12, Cartas de Jose Bernardo de Almeida, em Beijing, ao Bispo de Macau, Dom Alexandre da Silva Pedrosa Guimarães, em Macau, 1775-1779 — For the scores of letters, written by José Bernardo de Almeida, in Beijing, to the Bishop of Macao, Dom Alexandre da Silva Pedrosa Guimarães, between 1775 and 1779 —A suggestion of possible sources for this biography.

10 ABREU, António Graça d', Dom Frei de Alexandre Gouveia, Bispo de Pequim, in "História", Lisboa, (152) Maio [May] 1992.

11 PRITCHARD, E. H., Letters from Missionaries at Peking, in "T'oung Pao", 31 (2) 1934, p.12.

12 Qingshilu 清实录 (Chronicles of the Qing Dynasty), 1432, 19 b ó For the Chinese document which speaks of these promotions which speaks of So Dezhao (José Bernardo de Almeida) as the "[...] leader of the interpreters and the other westerners which he has brought with him to Jehol."

13 PRITCHARD, E. H., op. cit., pp. 18-21.

14 Apud PEYREFITTE, Alain, op. cit., p. 150.

15 CRANMER-BYNG John L., Lord Macartney's Embassy to Peking, in "Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, (4) 1957, p. 173.

16 PEYREFITTE, Alain, op. cit., p.285.

17 CORDIER, Henri, Histoire générale de la Chine, Paris, 1920, vol.3, p.381.

18 LO Shu-fu, A Documentary Chronicle of Sino-Western Relations, 2 vols., Tucson, University of Arizona, 1966, vol. 1, p.344, and vol.2, p.539 — for the commentary.

19 AHU: Maço [Pile] José de Torres, livro [bk.] V, no540 — Transcrição do Memorial de Jose Bernardo de Almeida e Alexandre de Gouveia, em Beijing, ao primeiro ministro da China, em Beijing, 19 de Agosto 1802.

— For the text of this memorial.

The secretary of the British embassy, John Barrow, learned of this same text in 1803, which he immediately commented in his Travels to China, published in the following year. For Barrow, our missionaries, by making all these accusations, stirred up yet more hatred and caused the imperial power to exercise greater vigilance over all foreigners resident in China.

The fact of the matter is that after 1799, with the death of the Qianlong Emperor and the subsequent death sentence of the previously all powerful Prime Minister He Shen, the protector of Frs. José Bernardo de Almeida and Alexandre de Gouveia, the situation of the missionaries in Beijing underwent considerably more difficulties.

start p. 161

end p.