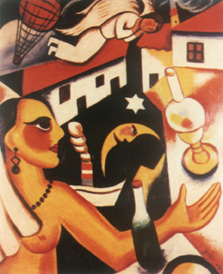

"A Late Symhony" (oil painting 1924, private collection).

"A Late Symhony" (oil painting 1924, private collection).

Through an extremely singular assimilation of a Matissean

register, the works of Júlio soon incorporated,

in sense of having made it their own, a deep orientalizing

inclination which eventually gave them one of their most

interesting global perspectives.

Through an extremely singular assimilation of a Matissean register, the works of Júlio soon incorporated, in the sense of having made it their own, a deep orientalizing inclination which eventually gave them one of their most interesting global perspectives.

That perspective, which was never really understood in its long and original course, started to materialize, becoming denser and denser, through his series of drawings in which nankin on paper became more and more important, defining a sort of immediate relationship between idea and execution which may certainly not be among its least important connections with that alleged orientalism.

We now know how traditional Chinese painting imposes such control of technique which makes the final results admit no change or correction, how it presuposes decidedness in the line, the discipline of the hand, abandoned to spontaneous gesture. Thus, Júlio did practise it throughout the years, and the possibility might even be considered of his growing interest in drawing having had to do with that search for discipline - an expression, necessarily, of an inner tranquility, of a certain sagesse. (1)

On the other hand, Chinese painting has also, for centuries, presupposed the "non-realistic" presentation of a certain place, favouring instead the idea of that same place, which appears only as a suggestion. A non-naturalistic value in which, without losing its place as the referent, Nature is always interpreted, that is, transfigured into a new language.

That was exactly the fact which rendered the discovery of Chinese tradition so important for modern western painting: the deviation by reference to naturalistic codes, which threatened to turn painting into a mere mimetism of the real, considering the latter as transparent, denseless data, that is, insusceptible of being interpreted.

On discovering the freedom of traditional Chinese painting, the modern artists in the West could give free vent to a conception of the work of art which was not anchored to a passive reality, but which sought, beyond its immediate surface, the signs of a deeper dimension. That was the way it undoubtedly happened with Matisse, as well as with all of those who were able to become aware of such an extraordinary possibility, as it later happened with the so-called American Abstract-Expressionists who rediscovered, in Eastern calligraphy, the expressive potentiality of gesture, as a sequence of an automatic register of emotions which was culturally sanctioned by surrealist theories of automatic production either written or painted.

It thus happened, giving a new impact to the capacity for inventing painting itself in the West, such as, in the beginning of the century, it had been necessary to discover Black art so that cubism might be built upon such foundations as were also decisive as a discovery of cultural worlds to which the West had remained closed during all the centuries of ethnocentrism which dominated it.

It was in that perspective that Júlio understood (and that it is rare in the Portuguese art of the present century) the importance of this discovery and was able to assimilate it with intelligence and originality. That is why the Nature he painted was never a naturalistic one but, instead, it was always interpreted; it was a personal understanding of Nature.

And it is certainly interesting to notice how the presence of animal and vegetal elements-birds, flowers, animals, or even the human figures which emerge almost as emanations of Nature, its complaisant inhabitants - is extremely close to the recurrent themes of the oldest plastic culture of China, namely, to those which, in the 8th century, guided the first academy of Chinese painting 'the brushwood', which was to have a decisive influence upon Western painting.

Simultaneously, his painting is always about essence, i. e. about the search for the elements and their representation as a "state of mind": thus, for instance, in the series Poet where the figure of the poet is a tutelary one and is supposed to represent not this or that particular poet, but the very concept of Poet.

This search for the essence (the word 'essence' is, by the way, the title of one of the books of poems which he published under the pseudonym of Saúl Dias) is as genuine in his plastic works as it is in his poetry, where the predominance of words referring to Nature is evident, in the same way as the economy of words and images he used is fundamental; sometimes evoking the Hai-Ku in his extreme simplification, he tried to achieve the highest and most intense form of poetic communication through maximum restraint.

Finally, it would be interesting to reflect upon the fact that calligraphic writing and drawing have always been so close in Eastern culture; but Júlio could not find a solution there, for he was a Westerner. Curiously enough, his poetic and plastic works always followed each other, evidencing the same anxieties and playing, on separate levels, upon that which he knew to be one and the same thing: the need for expressing a vision of the cloud which was dictated by his sagesse .

And that he did, keeping both fields apart, but never forgetting the fact that he was refering himself to a spirituality, almost to a mysticism, in the contemplation of Nature and Life which appertained to his way of understanding things.

And by so doing, Júlio was following an intuition suggested not by the mere understanding of certain values in European modernity, but maybe more profoundly by the deep bonds which have for centuries linked Portugal, the westernmost country in Europe, to a culture which manisfested itself in the East, and through the knowledge brought by the 16th century voyages of the Portuguese in their search for unknown worlds and which has been amply echoed in much of our art, from furniture to faience, from architecture to jewellery.

Júlio was, in fact, re-discovering that deep heritage in our own culture, materializing the Eastern aphorism which says that what is on top is like what is under. That was wisdom in him as well.

Translated by João Libano

T. N. (1)Wisdom, in french in the original.

*Poet, critic, essayist; Asst. Professor of Historical Arts of the University of Minho and member of the International Association of Crities of Arts.

start p. 72

end p.