"Macau has a floating population

which unlike that in our cities, is really

a floating one. Traditionally these people "are

born, grow up, marry and die on boats", The majority

only moves on land after death. Their boats are world-famous.

The Chinese junk has been continuously used as a symbol of

some exotic romanticism, associated with the tourist image

of South China. Nevertheless, the inhabitants-crew of

the Chinese boats have a less brilliant status. In fact, the

nostalgic fascination that this marine technology

seems to exercise, has been accompanied by

an obvious disinterest in the people".

Any anthropologist, or sociologist, working in Macau is immediately faced with the need of defining the boundaries of his research. Macau's social reality is highly heterogeneous. The small size of the Territory(1) fails to show its huge sociological complexity, and the researcher faces a society in which a wide range of social groups have proliferated side by side. These groups are mutually marked by primordial elements such as race, language and ethnic history (2). Hence, the following questions are pertinent: what makes these groups keep their identity without mingling through a cultural adaptation process after centuries of co-existence; and what makes the different groups hold together in a common society despite the said diversity and lack of apparent elements of union?

The equation of the multiple differences participating in this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this work; its aim is just to study one of its aspects, in the light of reflection arising from empirical observations that are now the subject of our research - the fishing community of Macau. South China's fishing people were the first inhabitants of the area currently known as Macau, and the neighbouring cities of today's Hong Kong and Guangzhou. These people were referred to more than a thousand years ago in Chinese texts. The existence of these people as a clearly defined group, now and throughout that considerably long period of time becomes the subject of our approach.

Macau has a floating population which unlike that in our cities, is really a floating one. Traditionally these people "are born, grow up, marry and die on boats". The majority only move on land after death. Their boats are world-famous. The Chinese junk has been continuously used as a symbol of some exotic romanticism, associated with the tourist image of South China. Nevertheless, the inhabitants-crew of the Chinese boats have a less brilliant status. In fact, the nostalgic fascination that this marine technology seems to exercise, has been accompanied by an obvious disinterest in its people. Discriminated by the land people, forgotten by the government, this population is practically unknown in terms of concrete data or any other sociological evidence.

The demographic census figures mere approximations: 10,000 people may be living permanently on boats and use them for a water-based livelihood; it is estimated that there are around three million people in these conditions in Guangdong Province; many more may live along the coastline from South-East Asia to Japan. Most of the local boat people are composed of fishermen, and the remainder are engaged in various types of transportation; a small minority work on land, and use boats only as their home. The fishing sector is the major extraction industry in Macau. However the lack of data makes the appraisal of its actual economic value very difficult.

South China's boat people represent an extreme case of adaptation to the environment. This is also one of the reasons why they are little-known; the study of a nomadic group living on boats encounters specific difficulties. The collection of statistical data of any nature becomes extremely difficult. The most conventional methods of data-collecting and sampling seem inefficient, in the presence of such fluidity and movement of the subject; the economic information obtained from fish dealers is doubtful, because they are afraid of interference by the government; finally, its bibliography in terms of the social sciences is very scarce and such a study has yet to be made in Macau. Now that our knowledge of the Chinese civilisation is fully documented, our lack of information in this area is felt more strongly. The social characterization of Macau's fishing community should base in scientific terms all actions set up or to be set up by the Government concerning this sector. All and all, becoming aware of this social-cultural reality is the first step to both overcome bias and attitudes based on ignorance, or misunderstandings, and to contribute to a more dignified human perception of this population.

South China's fishermen are divided into two large groups which are known, in Cantonese, by Tanka (蛋家) and Hoklou (鶴佬).

The Hoklou Group speaks a less known version of the Fukien (southern Min) dialect which resembles Tiuchew (in Cantonese Chio Chao), although it is difficult for the natives of this language to understand their centre of diffusion seems to have moved from the Fukien Province to the Swatow and Swamei areas on the North coast of Guangdong Province. They then spread to the North East, along the Fukien coast, and South East down to Hong Kong, where they are just a small minority of the local boat people living mainly in the Tai Po area. Although we have been unable to detect concentration of Hoklou in the area of Macau so far, that does not mean that they are not in the territory. The direct translation for the Cantonese word 'Hoklou' is 'Tall Man' which is a derogatory term. This seems to come from the fact that the first syllable of the word Fukien - that is Hok-Kien in that dialect, has the same tone as the word Hok-'gran' (Grus Chinensis in zoology), in Cantonese. Isolated as they are due to their difficult language, the Hoklous are one of the groups less mentioned in anthropological literature and, apart from sporadic references, we are unaware of any paper, dealing exclusively with them. Besides the language, a distinctive feature of the Cantonese boat people, signs of this sub-culture can be found through other external characteristics; we refer to certain details in the construction of their boats; these present main-rails stretching to the prow with drawings in the form of eyes painted on tacks and referred to by the Cantonese fishermen as "tai ngán kâi", (大眼鷄) which literally means "chicken with big eyes", a mockery as such drawings are uncommon to them. The miniature kept by the Chinese temple at Barra, in Macau, has the above characteristics, which further suggests that in the past there was a significant number of Fukien fishermen in this area(3).

The majority of the fishermen in the Guangdong province - and certainly almost the whole community of fishermen in Macau - are Tanka, which is the Cantonese word for the people living on boats and speaking Cantonese. This is a derogatory term and usually the Chinese characters for it are (蛋家). This is interpreted as "egg house(s)" or egg family(ies)" which is sometimes explained by the shape of a certain type of boat, used by these boat people. We have heard this explanation from many land people, and have also found it in the "Glossário do Dialecto Macaense":

"(...) The tanka is a fishing boat, or a short haul means of transport, which also serves as a residence. It is partially covered with a tunnel-shaped canopy, from which comes the name. Tanka (Etymon-ch), literally "egg house" i. e. egg-shaped house - possibly because the small boat, with its canopy, looks like a floating egg. The word 'ka' also means family, and this is why it is applied to the sea people (...)".

(Batalha 1977:277-8)

However, there exists another version, evidently more widespread in Hong Kong:

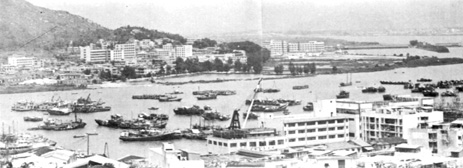

A view of Macau Inner Harbour.

A view of Macau Inner Harbour.

"(...) It is said that these people used to pay taxes in the form of eggs (...) the poor fishermen had no money, no silver coins tinkling in their pockets, probably they exchanged fish in the market for goods found on land. They raised poultry on board the vessel, and paid taxes with eggs to the tax collectors (...)And for this reason this people have been named Tan-Ka-a term which is simultaneously official and colloquial, logical and picturesque (...)".

(Kani 1967:6)

Even though interesting - whilst revealing how the land people see the sea people-these explanations are not satisfactory, mainly because in the old Chinese texts the boat people were sometimes known as " 蜑 " in Chinese. Although the pronunciation of " 蜑 " is the same as " 蛋 " tan, "egg", its meaning is very different (Kani 1967:6). We are therefore led to believe that the character 'egg' was used, amongst others, to transcribe phonetically the word Tan, which etymologically had another meaning. A different reasoning in the form of a hypothesis claims that the word was originally referred to an aboriginal tribe of South China, and later applied to the boat people (Lo 1963: Ho 1965: Eberhard 1968). We will be focusing on this matter in due course. For now as we lack evidence, let's take these assumptions as conjectures - the origin of the term remains unknown and awaits a philological clarification. Anyway, the word Tanka carries a disparaging stigma, and even though used among the fishing folk themselves, it is considered offensive when used by other people. This is somewhat identical to the manner in which ethnic minorities resent the manner in which the language expressions defame them, or the way they are denied a human status. Against this they call themselves (水上人) 'soi seong ian', which literally means "people on the water". The fact is that the sea people resent being discriminated against as a scorned social minority who, traditionally, occupied the lowest rank of South China's social stratification. The land people point them out as examples of sexual promiscuity and other less desirable characteristics, and it is always said that in old times they were banned from settling on the land, marrying land people, as well as sitting for Imperial Examinations.

The bureaucratic recruiting system in China was through public written examinations, organized by the State. On the one hand bureaucrats had, in fact, access to power - and on the other hand, the administrative structure required at least one bureaucrat in each district. In addition, examinations were open to every class; with this, Imperial Examinations took up a crucial role in social mobility. However, as we stated previously"(...) not all the Chinese were able to compete for these literary titles, as the State examinations were banned up to the third generation, to all individuals engaged in dishonourable professions, such as: quacks, fortune--tellers, astrologers, physiognomists, actors, descendants of prostitutes, executioners, government department servants, jailers and beggars. In 1733, the Emperor Iong-Tcheng included in the number of banned people, the Tan-Ka, a race of Autochthons engaged currently in a sea life, which was and still is considered to be inferior to the Chinese (...)".

(Gonzaga Gomes 1952:15)

Professor Chen Hsu-ching, who carried out extensive documentary research in this field, agreed however that although a small number of fishermen could have attained the lower ranks of bureaucracy, he could not find any Imperial Law, or other legislation excluding the Tanka people. This leads to the conclusion that banning was caused by local bias, and not by any official policy. (Chen 1949:109).

Pursuant to the above considerations all this seems justified as if fishermen were seen as belonging to a "race inferior to the Chinese", or as if the population in question was not, in fact, Chinese.

In fact the land people tell stories regarding their alleged physical deformities - one of which, collected by Barbara Ward (1965:115), states that the fishermen are born with six toes on each foot-and frequently the educated Chinese give them special anatomical features.

The confubalutory nature of many of these assumptions/suppositions can be found immediately by direct observation, since no morphological abnormalities can be seen as fishermen go often barefoot. On the other hand, there are certain physical features that make boat people easy to spot:

"(...) With the muscles well developed, strong chests and tanned skin, fishermen are the healthiest class among the Chinese people. They are short and sturdy, their lower limbs slightly shorter, probably because they have been spending most of their lives, over generations crouching in the low and narrow cubicles of their boats. This also changes their way of walking, which is easily spotted when they are seen in the streets (...)".

(Gonzaga Gomes 1949:34)

However, these physical traits which mark the fisherman (a darker complexion, a swinging walk, relative hipertrophy of the upper body in comparison to a relative hipotrophy of the lower limbs), could easily be explained by an adaptation to an aquatic way of life, rather than by hypothetical racial differences. In fact, this was the conclusion that Chen (1935), Balfour (1941), Ward (1965) and Anderson (1970) arrived at. This seems to be the official position of the People's Republic of China as well, since it does not include the Tanka in the list of its 65 national minorities (Fei 1981). The criterion of direct observation could also be applied in linguistic terms, Tanka as anyone can hear speak Cantonese, albeit with an accent and vocabulary related to their own way of life. The linguist, John McCoy, of Cornell University, who carried out some field research on the speech of the Kau Sai fishermen (New Territories, Hong Kong), found that the use of words related to fishing and life on board - even though a relatively small number - could cause a strange feeling to a native of the same language, who is not familiar with the respective context, as those words are used so often; this fact, together with the phonological differences (accents) could lead the researcher to exaggerate the varieties, which in fact are minimal in a linguistic relation (McCoy 1965-50). The author was therefore unable to find in the fishermen's speech any non-Chinese grammatical or phonological elements, supporting the hypothesis of their tribal origins. (McCoy 1965:60) It should be stressed that, contrary to popular opinion, the boat people do not have a language of their own, or in other words, South China's fishermen speak different languages - the so-called Chinese dialects - which refer to, like the various sub-dialects, the speech of the coastal regions of their homeland (McCoy 1965). However, it is also true that the vast majority of boat people remain illiterate; boat people very seldom marry land people (ethnic endogamy) and, when it happens, only boatwomen get together with land men (hipergamia), never the other way around (hipogamia) as far as we know; and the group has exposed itself to prejudices, which is part of its psychological characteristics. These are projected through the group's attitudes of reserve and distrustfulness towards strangers and authorities. The origin of South China's boat people has been the subject of many theories. Although the scope of our job is not the examination of the physical and cultural origin of the Tanka people, one should take into account all theories.

As we have seen, according to popular opinion and the scanty literature about the fishing community, the cultural differences found are due to the fact that they are not Chinese, i. e. they are not descendants of Han (漢)- unlike the other Cantonese people. If this supposition is not examined it will work as a myth, that is, people will take it as an explanation which, regardless of its validity, serves to justify attitudes and explain behaviour.

We will not focus on the Chinese encyclopaedists' narratives who say that the boat people, and other "barbarians", originated from animals. These narratives are compiled by Cheng (1935) and we will no longer mention them. Likewise, Westerners have speculated on hypothetical migrations from the Philippines, Malaysia or India (Menard 1965). However these inferences have no evidence, and the historical data, together with linguistical and ethnographical facts, support the idea that South China's boat people have lived here since they are known as a group.

One of the most credible theories is that the people are descendants of the region's aboriginal tribes. Our approach follows that of Wien (1954) who based his work on Eberhard. According to these authors, the boat people are descendants of the Yueh (粤); these who correspond to the 'Viet' people of Vietnam, were inhabitants of South China when the Han Chinese (in Cantonese Hon), coming from the North settled in this area 2,000 years ago. The concept of Yueh comprised many tribes, which were absorbed by the Chinese, or forced by them to move down South; one of these groups - the Tan, where the word "Tanka" comes from-resisted the process of assimilation, thus preserving their identity. This could have been the boat people's origin. However, according to Eberhard, the Yueh culture was not marked with distinct features, but rather it was the result of the mingling of different cultures, that preceded the designation of Yueh as a political concept in the VIIth century B. C. This fusion process - encompassing at least Yao, Tan and T'ai (or Chuang) elements-was interrupted by the advance of the Han and absorbed into its culture, (Wiens 1954:41-43). Well, if the Yueh culture comprised Tan elements these should either be part of South China's complex socio-cultural structure, or at least integrated in it partially; anyway these cultures could not have been strange amongst themselves. Furthermore there are no clues leading to the conclusion that this assimilation process stopped after the VIIth century B. C. In fact, there is evidence that in the later centuries, the Han culture absorbed what used to be Yueh - or expelled beyond its frontiers those who resisted the assimilation.

It seems therefore reasonable that, in the 2500 years which followed the emergence of the Yueh as a political concept, there had been plenty of opportunities for the Tan - being more accessible than the remote mountain tribes - to be assimilated by the neighbouring population. Finally, with the lack of biological, linguistical and cultural data on which to base the idea that the Tanka represented the survival of South China's protocultures, it seems difficult to refute the idea that the boat people are neither more nor less descendants of Han, than the other Cantonese people (Ward 1965:118)

Another theory supports the idea that the boat people comprise descendants of the land people, who sheltered at sea in times of war, or political crisis. An inspector of Shanghai's Marine Customs gives the following account:

"(...) During the Sung Dynasty there was an Emperor who was at war with his enemies. Having to participate in a campaign, he left the destiny of the nation in the hands of his two trustworthy ministers. It is a sad thing to have to relate that these ministers were irresponsible in their duties, to the extent of conspiring with the enemy. When the emperor returned triumphantly, he became so furious that he ordered the issue of a decree. From then on, the two ministers with their respective families and parents, their women and children, the household servants and their descendants, their domestic pets and their poultry were ordered to live on boats as to never again live on land. Furthermore, they were forbidden to appear as candidates for Imperial Examinations, neither could they assume any official position nor own any land (...)"

(Worcester, 1959:94-95)

A view of Macau Inner Harbour.

A view of Macau Inner Harbour.

Likewise, it is said that the boat people of the River Min,

"(...) are supposed to be descendant of certain groups which organized a revolt, in the beginning of the Manchu dynasty against the oppression of the conquerors coming from the north, and on account of this crime, were deprived of owning land - so dear in the heart of all chinese - being condemned to live, for ever, on boats (...).

(Sowerby, 1929:26)

Professor Chen Hsu-ching, during his research in Shannan, in Guangdong province, found a genealogical record of the Liang family saying that its ancestors had chosen this way of life to avoid hostilities during the Sung dynasty (Chan 1946:18-19). More recently, at Castle Peak, Hong Kong, some similar testimonies have been collected.

"(...)" Chau Wing-yiu, son of a fisherman, educated in Hong Kong and London Universities, thinks that the "floating" population descends from Chinese of the north, faithful to the Sung dynasty, that took refuge at sea to escape from the Monghols (...) many fishermen are direct descendants of the land people which had taken refuge during insecure times of Taipeng Rebellion, or in times of scarcity, in the XIX century.

There are still many people who recount the events of these periods, which were told to them by their grandparents (...)".

(Anderson, 1970:14-15)

Thus, all this seems to suggest that, during the course of history, demographic movements from the land to the sea have occurred, which further supports the theory that boat people are not of a different race. Currently there is a movement in the opposite direction - the technical innovations which have been introduced in the past 20 to 30 years (mechanization, refrigeration, trawlers, new types of deep sea fishing vessels, etc.), have been followed by a demographic movement towards the land, where fishermen can go unnoticed in the local population. Our observations in Macau confirm that those who settle on land tend to become less 'detectable' by finding new jobs and allowing them to school. So their origin goes unnoticed throughout the years, as people tend to hide it.

The above theories try to account for the origin of sea people. However, none of them seem to stand on solid ground. As a result of this, the following conclusion still stands as valid:

"(...) It is still unknown which tribe or race they belonged to or whom they mingled with(...)".

(Chen 1935:272)

Although the possibility of boat people being influenced by tribal features should not be put aside, there are signs that they are not a homogeneous group. On the other hand, land people do not seem exempted from the influence of the said tribal features.

At first, South China's fishermen, with their highly specialized way of life, present an extreme case of adaptation within the Chinese culture - which evolved from a society of agricultural origins; their nomadic life adapted to an aquatic environment prevented them from going to school. This kept them away from a civilization which evolved under the influence of a powerful written tradition. It is therefore only natural that the above conditions brought up a set of socio-cultural features respective to the fishermen that are still to be characterized. In other words, and recalling what has already been said, if the Tanka had remained socially apart despite co-existing nearby, the land people's attitude of not considering them Chinese, could be valid - not in a racial but in a cultural sense.

Thus, as seen before, the usual arguments that isolate the Tanka in social terms would be: prohibition to live on land, the exclusion from the Imperial Examinations and the practise of endogamy.

We are aware that pursuant to an Imperial decree in the VIIIth century boat people were allowed to live on land (Tien 1985: VIII), those who did were able to mingle with the land people, but for those who stayed at sea, it was almost impossible to enjoy any sort of schooling. This had serious implications, particularly during the old regime as we know. Nevertheless, we are more interested in considering this problem from a different angle. Some of the reasons which are often given, regarding the uniformity and continuity of the Chinese civilization, during a considerable span in time and space, are related to the existence of its flexible writing system, associated with certain historical circumstances which enable the rise of a bureaucracy. This kept talents flowing, thanks to a public examination system. One of the remarkable features of the examinations through which access was gained to the ranks of bureaucracy and consequently, the education required for sitting for the examinations, which sometimes lasted for over twenty years - focused mainly on classic texts, in particular the social doctrines of Confucius. By and by the bureaucrats stood out from the remainder of the vast society, as throughout the years and all around the country the confucian rules, values and ideas were followed. Their social behaviour was therefore shaped by it - they were the literati, the gentry.

san u-"Sacred fish" in the Temple of Barra (Ma Kok Miu)

san u-"Sacred fish" in the Temple of Barra (Ma Kok Miu)

Also, given the reputation of the literati it is not surprising that these ideal patterns were admired, even though they could not always be followed. These patterns were also used as guidelines for the social stratification by those classes aiming at the ascent to the higher ranks. Moreover, the sanctions on the social order were imposed by bureaucrats, who were themselves literati and this assured a wide influence of these patterns. (Fei 1946,1953; Ch'u 1957; Krache 1957). If the above is to be taken as valid, we could think that the social system was more homogeneous in respect of those sectors under the influence of the literati. On the other hand, a wider heterogeneity could be expected, both in time and space, in those sectors where those patterns were meaningless. The fact that, until recently, very few Tanka had access to any form of education could explain the assumption that their social organization had significant deviations from the ideal pattern of Chinese culture. However the facts collected do not give ground to this assumption. The language, the social structure, the personality and other cultural aspects of the boat people present variations which, in general, fall within the limits of variation found in the Chinese culture.

The traditional picture of the social isolation of the Tanka seems to minimize the fact that over the years boat and land people have been closely related in economic terms, regardless of their ethnic origins and cultural features that differentiate them. The fishing sector is not economically isolated as it is an economic sub-system of any town in which fishermen operate. It is mainly a branch of industry with lack of capital which depends on the extraction of a precarious natural resource - fish. This industry calls for a relatively high capital expenditure on boats and equipment, and it takes place in a culture where some expenditure is socially required - for example for a wedding - and high. There are several ways of getting the money needed, the most usual being through the fish dealer ( 魚欄 u lan), who is a landman, by means of loans. In exchange, the fisherman undertakes the selling at a reduced price of the fish to the creditor, and he then, re-sells it to the market. The fisherman receives the net revenue of the sale, i. e. after commissions to the dealer and retailer. The creditor's commission is not fixed and may change according to the amount due. Meanwhile, the fisherman buys equipment and other goods, often on credit, from retailers, who are also land people; the borrower pays what and when he can afford to; pursuant to tradition, all debts should be settled by Chinese New Year. This means that borrowing money from a fish dealer forces fishermen to buy on credit from retailers. This credit and loan system encompasses two aspects that must be pointed out: on the one hand, without it (the system) production would not be feasible long-term credits acting as lubricants on the economic systems on which they depend are not exclusive of South China; on the other hand, it is mainly a localized system - i. e. transactions are made through inter-personal relations, and both loans and credits are granted on trust rather than through a bank guarantee, or bondsman. It does not require any formality other than a gentleman's agreement. This system seems to be associated with the upsurge of inumerous small fish shops: on one hand the creditor has already got some money, on the other hand the number of borrowers that he may have enough trust in and therefore take the risk for is of course very limited. So, this market does neither follow the Government's policy nor free competition rules. Instead it is governed by inter-personal relations - social ties which create economic ties and economic relations dependent upon personal relationships. This is one of the reasons why fishing communities are relatively stable. This stability is in fact far superior to the one commonly, ascribed to them mainly by the gross caricatures that represent these communities as wandering nomads; without a permanent basis the fishermen would be unable to obtain the loans and credit essential to them. These inter-personal relations between the boat people and the land people, on which the fishing economy is based, and founded on a mutual understanding over a long period, need regular and frequent contacts, which often comprise entertainment in tea-houses and restaurants. In the light of this continuing interaction with people whose life styles they must adopt if they are to have some prestige in their society, the Tanka could only have kept a different culture if they had strongly rejected this assimilation process. That is what happened to certain tribes in the inner mountains of the Guangdong province - e. g. the Yao and the Li. However, an opposite trend has been experienced as it is foreseen that the current modernization process will speed up the cultural adaptation process towards the land culture.

To this end, we must stress that boat people have however retained some features which differentiate them from the Han culture or, at least, from the social pattern of the literati. These distinctive features will be examined in other works to be presented later; we will for now list very briefly those differences:

1) The fishermen do not have lineage or clans, and do not consider extended forms of kinship beyond the joint family; central position in the social organization of South China's rural communities (Freedman 1958, 1966; Baker 1968).

2) Some features of their marriage rites are not seen among the land people.

3) They use wooden figures instead of the "Ancestral tablets" (神主牌 san chu pai) to represent and venerate the souls of their deceased relatives.

4) They consider certain fish as sacred (神魚 san u), and when they catch them, they offer them to the Gods in the temples.

5) They consider themselves less vulnerable to the influence of geomancy ( 風水 fong soi, literally wind-water), than the land people are.

6) They have their own songs, quite different from those of the land.

7) They use a certain hat, and the women use a characteristic type of ear-ring and bracelet.

Below are some features that we referred to before:

1) They live mainly on boats, or in some cases in huts built on stilts on the shore.

2) They specialize in ways of life based on water: fishing, the transport of cargo and passengers, etc.

3) The dominant majority relegates them to the lowest rank in South China's social stratification.

4) The land people consider them a separate group; the boundaries of this differentiation are drawn by marriage constraints - they practice endogamy, even though hipergamy is allowed and hipogamy is unknown.

5) They speak Cantonese with slight variations in dialect; the vast majority remains illiterate.

From a different angle the fishing community has a cultural and social environment that in general is similar to other Chinese communities in other contexts. On the other hand, the features that have been specified above are not that important as they are part of superficial variations on a background of undoubtful Chinese characteristics. In spite of this, the boat people remain a distinct group, and one is led to conclude that their stigma remains unchanged which makes this problem even more intriguing: not that they are discriminated against because of their physical or cultural differences - we have seen that those differences are not as big as we thought - but because they are so similar and yet they are represented as if they were quite different. Everything would be explained if the land people 'saw' the fishermen as something that is not "Chinese": people who live on boats and make a living by fishing- and who do not have the qualities of agrarian respectability and make a living by transporting cargo, or 'even worse' passengers. The latter occupation which corresponds to the general public's idea of the waterfront - and consequently, the most typical one to them - is one of the ways of life of the Tanka. Among them there are many female 'captains' and this presents a clear deviation from the traditional role of women in Chinese Society. In fact, among the fishermen there are very few female 'captains' for social (obtaining credit) and physical reasons - deep sea fishing would be unsuitable to women. However, in sheltered waters, women whose husbands works on the land, or, for example, their unmarried daughters, engage themselves in the transport of passengers in small crafts in the dock and anchorage areas. It is interesting to note that the Macanese dialect has a special word for these women the "tancareiras". The masculine of this word is used to refer to the whole of the boat people - the "tancareiro" is applied generally to the fishermen, even though as pointed out, it is a stereotype, which seems to be able to captivate the imagination of the land people (cf. Batalha 1977:277-8; Senna Fernandes 1950).

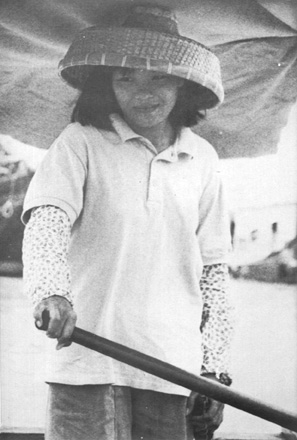

A "Tancareira" - a woman in charge of transporting passengers in Macau Inner Harbour.

Anyway, no matter how many pseudo-characteristics are granted to the boat people, which are just ethnocentric projections of the land people, the explanation of how some cultural differences remain has still to be given. The way researchers have been dealing with the matter makes any conclusion difficult to arrive at. For example, it was suggested that the "sacred fish" cult could prove the tribal origin of the population, as being related to the Yueh cults of dragons and serpents (Eberhard 1968); however it was also accepted that it could be just another form of adaptation to the aquatic life by recognising the mysterious nature of certain sea animals (Anderson 1972); or it was suggested that these and other elements, for example the bracelets and earrings, presented merely some of the many regional variations found in other parts of China and are just representing distinguishing marks and local pride (Ward 1965). This last idea seems to be more reasonable, and we would prefer to develop it as assumption. This seems to lead to the interpretation not in opposition but rather in addition to these cultural features as "social symbols": in other words, instead of trying to understand this culture abstractly, it appears necessary to see it "in action", i. e. in a social context. This can be better appraised if we take a specific case. Let us take, for example, the variations in ethnic costumes, and consider the different bamboo hats that are characteristic in South China folklore. Everywhere the need to protect the head from the sun is emphasized; the more important people carry parasols while the working class cover their heads with hats. There are several types of bamboo hats, and these are generally identified with the different ethnic groups revealing thereby their preferences. These differences go almost unnoticed in urban areas but nowadays can still be seen in the rural areas of the New Territories, in Hong Kong: "(...) The fishermen use a type of bamboo hat that has the shape of a bowl, which is inexpensive, but strong enough to fit on the head as an inverted bowl. It is not so vulnerable to squally winds like the hats with broad flaps and, therefore is preferred by the people of the sea. The people of the land call it the Tanka hat, whereas these people call it "bamboo hat". It is very rare to see the land people with these hats (...)".

(Blake, 1981:111,)

On the other hand, Hakka (客家) farmers use another type of hat, which is known by this name:

"(...) This type of hat consists of a bamboo interlaced disc of approximately 40 cms in diameter. It has an opening at the centre that fits to the. head. Above the opening a piece of cloth is folded which is tied with a band that goes around the brim and below the chin. In the rim of the disc is stitched an edging of cotton cloth, with a width of about 4 cms. This edging gives a feminine touch to the hat and has simultaneously a practical and expressive value. It protects the face from the sun and protects the skin of the face. It also acts like a veil that emphasises female modesty. This hat is used exclusively by women (...)".

(Blake, 1981:109)

1 Statuettes used by fishermen to represent the deceased relatives exhibited for sale by a seller in Macau.

2 A symbological miniature of the foundation of the Temple of Barra (Ma Kok Miu).

Interesting enough, in other regions the same hat characterizes other social groups:

"(...) I have observed in films about a commune in the region south of Paoan (in the province of Canton) that the women used "Hakka hats" and that the men used hats in the shape of a bowl (...)".

(Blake, 1981:117)

The hat with the fringe which is generally associated with groups of 'Hakka' language, has regional features, with many variations. These can even exclude other Hakka groups in other geographical areas. This refers to the 'sense of positions' of some elements of identity, of community, that at times, were thought to be deeply rooted in its racial or cultural substratum. We are probably bringing up a subject that may lead us to a better understanding of the problem we have been focusing on: an ethnic group which does not seem to derive its identity from the same cultural features everywhere, but from the sense of position derived from the role it plays in a social context instead. In this case the cultural polarity between the boat people and the land people conceals a relation of social inter-dependency and is consistent with an explorative pattern of certain resources based on an organization of some roles - fishermen vs. farmers, labour force vs. capital, etc. We have already established that the fact that some cultural differences remain unchanged does not seem to make sense in terms of tribal stability - for, as seen before, the continuous interaction might have given way to a process of cultural adaptation.

Now, I would like to attempt to go a little further by suggesting that these groups are aware of and maintain these differences during - and not despite this interaction. Although the process of interaction leads to a process of cultural adaptation, it does not necessarily eliminate the boundaries between ethnic groups, but on the contrary, it may lead to its ossification. It stabilizes the differences between each group, according to the position that each of them has in a process of social organization of their cultural differences. Hence the boat people's identity seems to be not so much related to their racial or cultural isolation, but rather to their social relationship with the land people. This relation of alterity is expressed dramatically in one of its sayings, in which they portray themselves as: (水上一條龍;陸上一條蟲"soi seong yat t'iu long; lok seong yat t'iu ch'ong" (true dragons at sea; miserable worms on land).

1 An association of a clan in Macau.

2 An association of natives in Macau.

3 "Lanes" - fish merchants in Macau.

Although the local traditions and external influences give way to a clear contrast in the social context of Macau, it should be taken into account that the former, have a remarkable wide range of features. The Portuguese administration adopted a 'laissez-faire' attitude of not interfering in local customs, allowing a relatively free expression of the traditional social organisation, provided it does not interfere with the status quo. These cultural differences among the local communities, even though generally without causing erosion at the level of the basic social structures and fundamental values, at times assume "ethnic niches" which are a rhetorical pretext of some being more 'Chinese' or more 'civilised' than others - the two categories being used as synonyms.

Among the Chinese, the family name and the genealogical connections, the language and dialect, the place of birth, and professional specialization are the traditional criteria which classify persons or groups and structure the interaction. Sometimes the application of these criteria puts fishermen beyond the civilization boundaries. However, anyone who has been in touch with the boat people knows that they claim that theirs is a Chinese origin regardless of their culture being changed by a process of adaptation that the majority of the land people does not have to face. The analysis of the polarity between the boat people and the land people brings up, however, a complexity of social ties which guarantee a certain kind of order, in a context where a more superficial appreciation could see the germs of anomy. This process of social organization of the cultural differences in Macau and South China, seems to lack further analysis and research.

Translated by João Libano

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Eugene N.

1970 The Floating World of Castle Peak Bay. Washington D. C.: American Anthropological Association.

1972 Essays on the South China Boat People. Taipei: Orient Cultural Service.

Balfour, C. S.

1941 "Hong Kong Before the British". T'ien Hsia Monthly, vol XI, pp 330-352,440-464.

Baker, Hugh

1968 Sheung Shui, A Chinese Lineage Village. Palo Alto: Standford Univ. Press.

Batalha, Graciete Nogueira

1977 Glossário do Dialecto Macaense. Coimbra: Instituto de Estudos Românicos.

1987 "Este nome de Macau..." Revista de Cultura, n° 1, pp 7-15.

Blake, C. Fred

1981 Ethnic Groups and Social Change in a Chinese Market Town. Hawaii: University Press of Hawaii.

Chen Hsu-ching

1935 "The Origin of the Tanka". Nankai Social and Economic Quarterly, vol 8, n° 2, pp 250-273.

1946 Tanka Researches. Canton: Lingnam Univ. Press.

Ch'u T'ung-tsu

1957 "Chinese Class Structure and its Ideology". In: J. Fairbank, ed., Chinese Thought and Institutions. Chicago: University Press of Chicago.

1961 Law and Society in Traditional China. The Hague: Mouton.

Eberhard, Wolfram

1968 The Local Cultures of South and East China. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Fei Hsiao Tung

1964 "Peasantry and Gentry: An Interpretation of Chinese Social Structure and its Changes".American Journal of Sociology, vol LII, n° 1, pp 1-17.

1953 China's Gentry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Freedman. Maurice

1958 Lineage Organization in Southeastern China. London: The Athlone Press.

1966 Chinese Lineage and Society. London: The Athlone Press.

Ho Ko-en

1965 "A Study of the Boat People". Journal of Oriental Studies, vol 5, n° 1-2, pp 1-40.

1966 "The Tanka or Boat People of South China". In: F. S. Drake, ed., Proceedings of the Symposium on Historical Archaeological and Linguistic Studies on Southern China, Southeast Asia and the Hong Kong Region.

Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp120-123.

Kani, Hiroaki

1967 A General Survey of the Boat People in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong: New Asia Research Institute.

Kracke, E. A.

1957 "Religion, Family, and Individual in the Chinese Examination System" In: J. Fairbank, ed., Chinese Thought and Institutions. Chicago: University Press of Chicago, pp 251-268.

Lo Hsiang-lin

1963 Hong Kong and its External Communications Before 1842. Hong Kong: Institute of Chinese Culture.

McCoy, John

1965 "The Dialects of Hong Kong Boat People: Kau Sai". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol 5, pp 46-64.

Menard, Wilmon

1965 "The Sea Gypsies of South China". Natural History, vol 74, n° 1, pp 12-21.

Senna Fernandes, Henrique de

1950 "A-Chan, a Tancareira". Reeditado em NAM VAN Contos de Macau. Macau: Edição do autor, 1978.

Sowerby. Arthur de C.

1929 "By the Waters of the Min". China Journal, vol 10, pp 21-28, 243-248.

Tien Ju-Kang

1985 "Foreword". In: Barbara E. Ward, Through Other Eyes. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Topley, Marjorie

1964 "Capital Saving and Credit among Indigenous Rice Farmers and Immigrant Vegetable Farmers in Hong Kong's New Territories" In: R. Firth and B. S. Yamey, eds., Capital, Saving, and Credit in Peasant Societies. Chicago: Aldine, pp 157-186.

Ward, Barbara E.

1955 "A Hong Kong Fishing Village". Journal of Oriental Studies, n° 1, pp 195-214.

1965 "Varieties of the Conscious Models: The Fishermen of South China" In: M. Banton, ed., The Relevance of Models for Social Anthropology. London: Tavistock, pp 113-138.

1966 "Sociological Self-Awareness: Some Uses of the Conscious Models".Man, vol 1, n° 2, pp 201-215.

1967 "Chinese Fishermen in Hong Kong: Their Post-Peasant Economy". In: Maurice Freedman, ed., Social Organization: Essays presented to Raymond Firth. Chicago: Aldine, pp 271-288.

1985 Through Other Eyes. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Wiens, Harold Jacob

1954 China's March Toward the Tropics. Hamden: Shoe String Press.

Worcester, G.

1959 The Junkman Smiles. London: Longmans.

** The research behind this article was carried out under a scholarship granted by the Instituto Cultural de Macau (I C M), whom we are very grateful to. As it was written to conform to one of the conditions agreed with I C M, it is not without reserve that I present this text. It marks the end of the first atage of a Social and Cultural Anthropology research on the fishing community of Macau. The short period in which it was written served as a reflection break in the field study I am currently undertaking. With this purpose in mind I aimed at a well informed public although not necessarily specialized in Anthropology or the ethnographic field focused in the article.

NOTES

(1)The total land area of the territory of Macau is 15.5 square kilometres, of which 5.4 sq. kms. pertains to the peninsula, 3.5 sq. kms. to Taipa island, and 6.6 sq. kms. to Coloane island.

(2)According to the demographic estimation based on the last census of 1981, the population of Macau is 426,000, of which 6,500 live on Taipa and 3,700 on Coloane. The population density is 25,200 inhabitants per square kilometre in the whole of the territory, and 68,800 per square kilometre in the Macau peninsula. However these figures are just a rough estimate as it is difficult to assess the number of illegal immigrants who, since China's open-door policy in 1979, have been flowing continuously into the territory daily. Only about 3% of the overall figure are of Portuguese origin, the majority of whom are Euro--asian (hetero-descendants of various cross-breeding) who show a preference in using Chinese as their language of communication. The Chinese majority is divided into different language groups (dialects), Cantonese being the prevalent, and acting as lingua franca between the groups. Cantonese people are also sub-divided into groups with small dialect variations and, apart from these, there are pockets of Tiuchew (Chio Chao) from the Swatow area of the Guangdong Province, and the Hakka, whose origin has not been determined. The various languages are supposedly associated with small cultural variations, and this also conditions interaction. Finally, the territory has received migrations from groups originated from several areas in the region experiencing economic and political tension (Vietnam, the Philippines, etc.). The European group which lives in Macau on a temporary basis should also be added to this melting pot.

(3)The Chinese Temple at Barra, Ma Kok Miu (媽閣廟) is dedicated to goddess A-Ma (亞媽) which literally means "Mother", referred to as the protector of the boat people, Tin Hau (天后). This is the most significant building for Macau's boat people and is located at the entrance of the Inner Harbour, which shelters the majority of the territory's fishermen. The Barra Pagoda, from which the name Macau derives, was there before the arrival of the Portuguese who also referred to it. Graciete Batalha confirms it without quoting any sources: "(...) at the time, the tiny population of this peninsula was mainly formed of fishermen from the Fukien province, and it was they who erected the aforementioned temple at Barra, establishing there the cult of the goddess of A-Ma (...)". (Batalha 1987:12)

Translated by João Libano

* Dipl. in Clinical Psycholgy (ISPA), Lie. in Ethnological and Anthropological Sciences (ISCSP), Mastership in Social Anthropology (King's College, Cambridge) Scholarship holder of ICM.

start p. 9

end p.