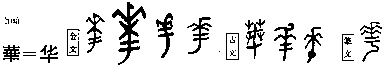

Hua

(flourishing; prosperous; brilliant)

Hua

(flourishing; prosperous; brilliant)

PRELUDE

Decidiram os organizadores deste Encontro que a sua língua veícular fosse o Inglês. Assim, e até para evitar eventuais desentendimentos oriundos, não das diferentes culturas, tema do nosso encontro, mas de várias línguas em presença, direi estas breves palavras de saudação em Inglês.

First of all I want to welcome all of you, especially those — as the Chinese would say — 'coming from afar guests'. Our humble and small Association feels really honoured with your distinguished presence. I am sure we will have the opportunity to learn many valuable things from your rich and various experiences. Our thanks also to the Cultural Institute of Macao, here represented by its President, Dr. Gabriela Pombas Cabelo who has organized this meeting. A very special thank to Dr. Gary Ngai, • whose dream, first mentioned to me last year, is coming true today.

I said small Association not out of modesty. We are, indeed, very small in almost all aspects you can imagine of, except perhaps in hopes and expectations.

When I arrived in Macao some ten years ago, this territory had a total area of sixteen square kilometres, the city itself only having six square kilometres. That was still the situation when a few years later, half a dozen pioneers created the Associação de Literatura Comparada de Macau (Macao Comparative Literature Association).

The Macao Comparative Literature Association started then, in a sort of equilibrium with the size of the city. Looking backwards, one could, I guess, go on drawing parallels between figures of 'natural' and 'cultural' dimensions.

For instance, the University of Macao which soon will be turning sixteen, had existed little more than six years at the time of the creation of our Association — exactly the same number as the kilometres of the city — whereas the Department of Portuguese Studies had more or less sixteen full-time teachers, exactly the number of kilometres of the whole territory of Macao.

Due to constant land reclamation, and according to the most recent topographical data, the territory of Macao has now an area of twenty three square kilometres.

I can see the smiles in your faces. It does look minimal, this difference of seven square kilometres, even if we consider their possibilities in vertical terms, the obvious architectural and urbanistic rule in Macao. However, if we think that these seven kilometres represent an increase of one third of the territory's whole original area in less than ten years, than it can be considered an amazingly big difference. And, from that point of view, are not we entitled to consider our city... how shall I put it... enormous? Or, in other words, we are small all right, but we have the capacity to grow fast.

As we are physically growing not out of any gift of Heaven, but by Man's effort, I can see no reason why we should not be able to grow culturally, in our own field with the same vigour we can see all around us.

In fact it seems to me that in terms of Comparative Studies, both for Literature and Culture, this practice of reclamation is already going on. In the sense that, where yesterday there seemed to be no space at all, there is today a new territory ready to be measured, analyzed and in a word, worked.

When a Chinese scholar of Macao presents, in a university of Guangzhou, a Thesis on 'Macanese Literature', she is, in fact, reclaiming land. When some time later she presents her work to an international conference in Europe, a paper she called The Cultural Importance of Macanese Literature, we can see that she has gone one step further: she has now built something on the ground she first defined and prepared.

If the area of Comparative Literature studies in Macao has increased one metre or half a kilometre since the creation of our Association, I do not think it is for our generation to measure. I believe what is important is what Macao people experienced when confronted with Dr. Wang Chun's• work1 — in a conference organized by the Macao Comparative Literature Association and described by one of the participants as an historical moment.

The fact that up to that moment, the literature written by the so-called 'Macanese' (the Eurasians of Macao, who we can say are the symbolic representation of the unique multicultural soul of the city) had never been the object of any study by any Chinese scholar. And very few from Portugual either. At that moment intellectuals of the three communities were meeting for the first time on 'Macanese' ground, made common by Dr. Wang Chun's work. It made obvious our sense of belonging together to a special place and to its own special culture, which is something very rare indeed in Macao, no matter how many clichés we make about the mixture of West and East. The cliché had become an emotional experience.

But that is not all. Other Chinese scholars have meanwhile been publishing articles on this part of the Literature of Macao. And others are actively engaged in research, either into the literature written in Chinese or the literature written in Portuguese, locals or expatriates, mostly to be presented as Ph. D. dissertations in Chinese universities. The fact is that Chinese scholars from Macao, coming from a sort of a three dimensional cultural world, speaking the three languages-culture of the territory, seem to be better positioned than most for these Comparative Studies.

I do not pretend immodesty to the point of suggesting that the Chinese members of our Association are better, or have greater responsibilities than their colleagues from other cities' or countries' Associations. But I do not think that we should miss the occasion to stress their basic potential advantage. Indeed, being familiar with the Portuguese cultural works as well as, of course, with the Chinese works, they are in an ideal position to interpret the two literatures and the two cultures. They are the ones that can really take some sort of global look, which I find promising in terms of a multicultural city like Macao.

Although in our Association we have not yet reached one active scholar per square kilometre, if the land reclamation happens to slow down we can catch up with it very easily.

It is interesting to note that although the tradition of 'giving lands to the world' has been traditionally associated with the Portuguese, at the moment in Macao it is the Chinese who are contributing, at a much larger scale to the modern adventure of land discovery and giving land to the world. The reasons for this on the Portuguese side are too complex to be brought up here. Of course, the languages probably being the instruments of this twentieth century navigation, our recent official insistence on teaching Portuguese and tending to forget the importance of learning Chinese, has turned against us. Fortunately it may turn out a blessing in disguise for the Chinese...

The situation being as it is in Macao, what we need to join the dance as a real partner on the Portuguese side is, above all, literary translations. As long as as a community we cannot read what the other community writes, we can never speak, seriously, of a comparative literary study. Since we have lost so many centuries in the field of Sinology, it is out of the question to win the remaining four years until Macao returns to mainland China. But we may try not to loose them entirely.

And that is why the present director of the Macao Comparative Literature Association puts such a great emphasis on the task of translation. Our vice-president, Dr. W. W. Huang has recently given the example — he himself translated a collection of Portuguese folk tales into Chinese. 2 Not knowing Portuguese he has used an English version which is not ideal but, it is obviously very much worthwhile.

Our Association is not only very small but also very poor. The paradox is the usual — we do not receive more money because we do not do more things, and, of course, we can not do things because we do not have the money. Besides, Macao Comparative Literature Association is also very young and so naturally, rather inexperienced.

To help its members, the Association needs help. We believe this is the occasion to ask, very formally, but also very sincerely, for the cooperation of the International Comparative Literature Association in the person of its president, Dr. Gerald Gillespie. As well as the collaboration from associations of China, namely the one from Guangdong, whose president Professor Rao is already involved in 'Macanese things', due to having so many post graduate students in Macao, we also need the help of the Portuguese Association, represented here by the nicest hostess we ever had, Prof. Margarida Losa, at the last Congress, in May, in Oporto. Apart from many other talents, I happened to find out, with the greatest delight, that she is also a student of Chinese. It is so encouraging to find a Portuguese tongxue·...

I do not forget the members of the Israel Comparative Literature Association and the Netherlands Comparative Literature Association, here with us: both Prof. Ziva Ben-Porat from Tel-Aviv University and particularly Prof. Segers who showed me his interest in Macao as a living laboratory of daily cultural interchange and permanent reshaping of cultural identity. From his knowledge and teaching experience in this new and exciting field we still expect to profit in ways yet to be defined.

Please do not be afraid that we will ask you for your money. What we would really like to receive from you is new ideas, information and opportunities for our members, who are involved in research programs — to attend courses, seminars, workshops, either organized at your own universities or preferably in Macao.

Thank you very much.

INTRODUCTION

The term 'literature' is complex enough. I can still remember the definition, often repeated by one of my former professors — the one I most respected and admired. "Literature is this and that and plus, that which is not yet literature." The term 'Macanese' is the most polemical word in Macao's fundamental vocabulary. So, the two together can become something quite hot; as the Portuguese would say, a 'batata quente', a 'hot potato'. The underlying idea being something that, as soon as you receive it, you try to pass on to others, as fast as you can, to avoid burning your fingers.

Today, having this 'hot potato' in my bare hands, and being supposed to handle it for a reasonable amount of time — for the sake of the Introduction — I really feel puzzled at how to start. How shall I begin? Especially because unlike Elliot's Prufrock who did not dare disturb the universe, I would like to inflame, rather that moderate, this round table.

Let us make a visit to a translation course that I taught in the University of Macao. In the beginning the students would always use expressions such as 'Literatura da China' ('Literature of China') or 'Cultura de Portugal' ('Culture of Portugal'), instead of the more Portuguese and eventually differentuated expressions 'Literatura Portuguesa' ('Portuguese Literature') or 'Cultura Portuguesa' ('Portuguese Culture'). For native speakers of Chinese it seems very difficult to understand the nuance between each kind of expression, due of course to grammatical differences, mainly in class words, which do not entirely correspond in the two, or three languages here evolved.

I would like to highlight the real difference in meaning, that Portuguese speakers feel in those pairs of expressions, in order to try to make it work as a differentiating concept in the context of 'Macanese Literature'. Or, shall I say 'Literature of Macao'?

It seems to me that 'Literature of Macao' raise no major problems, being a sort of a 'cold and tasteless potato': anything written or published in this place, using one of the languages present, that is the official ones, Chinese or Portuguese, will be immediately entitled to it. I can imagine Dr. Zheng Waiming• will not agree with me, since on one hand, he seems to be much more liberal in the question of the languages. On the other, a little bit more restrictive in terms of themes.... but I hope that later on, during our discussion, he can better explain his own concepts.

'Literatura de Macau' seems to me a comfortable but rather meaningless label. A Chinese from mainland China or an expatriate, a huqiao,• as well as a local born Chinese, as long as they work here can claim it equally as a locally born or locally raised Portuguese or an expatriate Portuguese can. That is what is happening in the field of the plastic arts, especially in painting, where the painters of Macao include natives from many countries and languages, some of them having no relation whatsoever with Macao's old or recent history. Which does not mean that they are not creating today's history and are very important indeed.

Whereas 'Literature of Macao' leaves everybody indifferent, 'Macanese Literature' arouses almost everybody. 'Macanese Literature' is of course, the works written by 'Macanese authors'. But who is a 'Macanese author'? The question lies of course with the word 'Macanese'. Up to very recently there was a sort of community agreement. The 'Macanese' were Eurasian, mostly from Chinese-Portuguese marriages. So 'Macanese Literature' implied a genetic criterion while 'Literature of Macao' had a geographic one. Although not very appealing due to some kind of racial prejudice, it has its own points. We know that the specific Eurasian community of Macao is spread out over almost all the world. So their works written anywhere and in any language would, automatically become 'Macanese Literature'. And probably very well, as is the case of a recent book of memories (of Macao), written in English, and titled The Wind Amongst the Ruins, by the 'Macanese' Edith Martini, published in New York. 3

So, to summarize: while 'Literature of Macao' is a big territorial bag, where all communities and languages, and, even different literary systems can coexist, 'Macanese Literature' is a sort of tiny little pocket inside the big bag, reserved for the works produced by one of the territory's communities.

Now if we accept Dr. Zheng Waiming's thesis — and I can see no reason why we should not, not only because it seems so reasonable, but also because he puts it in such an elegant and delicate way — "[...] with the passage of Time, it is only natural that Chinese Literature, in its large sense, will include the works of Hong Kong and Macao [...]," we will have to admit another factor — nationality — which still complicates the definition of 'Macanese Literature'. And what about the present moment, this period where Time has somehow not yet passed over Macao, how shall we differentiate and classify it in order to study it?

And if I agree that in the future the inclusion of 'Literature of Macao', namely the one written in Portuguese in the Chinese Literature, has to be considered, I have for the sake of logic to admit that the 'Literature of Macao', past and present, namely the one written in Chinese until at least 1999 can be included in Portuguese Literature in its large sense, as well.

Yes, why not? It seems such a fascinating idea, so enriching for the Portuguese side. (I can only speak of my side...) As actually it is nothing new... There is, for instance, this fantastic Aomen Jilue· (Monograph of Macao),4 in the beautiful translation5 of the great 'Macanese' sinologist Luís Gonzaga Gomes, work which I have no doubt has been adopted by the Portuguese community of Macao as one of its most cherished works of art. So cherished that it even originated another work of art by a team of Portuguese architects, about the city whose images have as subtitles lines of poems from the Chinese book. That means that the most Chinese of all Chinese books about colonial Macao belong synonimously to Chinese and Portuguese Literature. That is what I would consider to be the cultural miracle of the 'Literature of Macao': it is not only multilingual and multicultural but also multinational.

Within it though, it still remains to define, in this "pre-post colonialist period" as the Hongkongnese historian Zheng Miaobing· 6 has so adequately called our time, the corpus that we, who live in Macao usually call 'Macanese Literature', written by the Eurasians, in Portuguese (with the only exception, that I know of from Edith Martini). It is mostly characterized by a distinctive praxis of their authors, who move quite freely from one culture to another,. speaking both Portuguese and Chinese — a personal situation which is obviously reflected in what they write, more than how they write.

They are generally texts about Macao, and about the 'Macanese', that is about the Chinese and the Portuguese in Macao and their descendants. There are also quite a few about Chinese only, namely the short stories of Deolinda da Conceição — not many about the Portuguese only.

Of course they belong to Portuguese Literature, being written in Portuguese, by Portuguese citizens, in a territory administered by Portugal and formally belonging to the Western literary system. But having been born and grown in Chinese land, the texts, like their authors, are so fertilized by this Chinese soil that it is somehow difficult to put aside any intimate relationship with Chinese Literature.

Some Chinese scholars, like Wang Chun for instance, have detected in them some formal characteristics which generally belong to the Chinese literary system. I myself think that is specially true in terms of the culture conveyed by them, rather than in their literary strategies. [...].

There is a poem by Leonel Alves, a 'Macanese' poet to which my above mentioned friend and colleague called my attention. I find it particularly interesting because it reflects the way a 'Macanese' sees himself: not just a mixture of two parts forming a different one, neither here or there, but a permanent dynamic tension of two worlds:

"Dark is forever the colour of my hair,

Chinese eyes, Aryan nose,

Asian spine, Portuguese chest,

[... and he goes on...]

Heart Chinese, soul Portuguese."7

In this sense only the Eurasians are 'Macanese', although a few Portuguese and a lot of Chinese are also 'born in Macao', the real meaning of the word 'Macaense' in Portuguese. Because only born in them, like in the city itself, was this kind of personality who adopts both cultures as their own. In other words, the 'Macaneseness' is more of a praxis than a birth certificate. No Chinese would ever consider himself a 'tusheng', the Chinese equivalent for 'Macanese', born in the locality. And the very few Portuguese who would seriously describe themselves as 'Macanese', probably 'quase macaense' ('almost Macanese'), will feel obliged to define why: due to the fact that they lived here all their lives or married a Chinese or a 'Macanese', or speak Guangdongnese.

While the 'Macanese' tend to use their writing as a search for a 'Macanese' soul, looking and writing from the inside, the theme of the 'wo shi shei ';• the Portuguese expatriates tend to seek the exotic in Chinese Macao or the 'Chineseness' of the Chinese in their writing. When they write about themselves it is usually the theme of nostalgia, the point of view of the person in exile. Exile can be something very appealing to the Portuguese. But I will not elaborate. [...].

One last point. For the so called 'Macanese Literature', and as I said before, I would prefer to speak about contacts, daily contacts with Chinese literature and culture, rather than literary influences in the sense of what foreign elements we can find in this national work. And this for another reason: up to what point is Chinese Literature foreign to a 'Macanese'? Please do not answer me with the argument that 'Macanese' as a rule do not read Chinese. Stories, novels, poetry, theatre, opera, literary culture in the broad sense, does not circulate only in books. It is also in the air. It circulates orally. And the 'Macanese' community breathes Chinese culture, maybe more than Portuguese culture, at least in recent years. For them, even though traditionally illiterate in Chinese, the real sharing of cultural codes is very probably a better instrument to NOT misread the cultural text than a very good efficiency in reading characters would be, acquired outside by a foreigner, without any real life to support it.

To summarize: in one hand, the inclusion of 'Macanese Literature' in Portuguese or Chinese national literatures is not only provisory but also irrelevant — whatever makes its 'Macaneseness' depends on the historical moment and is independent of the language it is written in. From the oldest 'Macanese' poems written in patois, a sort of Creole from the Portuguese, until our age where Portuguese is dominant, with the only intrusion of English being the case of Edith Martini, I can very well see the future open for 'Macanese Literature' to be written in Chinese as well.

The fact that the so called local administrative localization has, even for me, something of enormous value for the young generations of 'Macanese', who can now speak and read/write Chinese as well as Portuguese. Nobody can foresee what will they do with this new skill. Apart, of course from becoming local leaders as the government expects. I myself have total confidence that some of them will not waste this enormous cultural instrument which is being put in their hands just on administrative and political matters.

So being, the 'Macanese Literature' can be many things plus that which is not yet. It is this openness, characteristic of the 'Macanese' culture and community, that is the most enthusiastic challenge to the whole territory of Macao. Because, let us admit frankly, if it were not for the 'Macanese' both in their physical selves and in their spiritual and cultural productions (among which, the city, both in its concept and design as well as architecture, is one of the most prominent) what other cultural meaningful and permanent mixtures could we find to have happened, in the past as in the present, between the eastern owners of the land and the Western people who have dared to come all the way from the da xi yang guo· to settle here?

NOTES

1 WANG Chun, Macanese Literature of Portuguese Expression, in "Review of Culture", Macau, (25) October-December 1995, pp. 221-240.

2 Dr. W. W. Huang's collection of Portuguese folk tales into Chinese.

3 MARTINI, Edith, The Wind Amongst the Ruins, New York, Vantage Press, 1993.

4 YIN Guangren• (TCHEONG-Ü-Lâm) - ZHANG Rulin• (IAN-Kuong-Lâm), Aomen Jilue (Ou-Mun Kei-Leok). • See: ZHAO Chun Chen, • "Monograph of Macao" and its Annotations, in "Review of Culture", Macau, (19) April-June 1994, pp. 102-109.

5 TCHEONG-Ü -Lâm - IAN-Kuong-Lâm, GOMES, Luís Gonzaga, trans, Ou-Mun Kei-Leok: Monografia de Macau, Edição da Quinzena de Macau [...], Lisboa) Macau, [Leal Senado] Tipografia Martinho, 1979.

6 MIAOBING, Christine Zheng, Macao: A "pre-post-colonial" Era, in "Review of Culture", Macau, (19) April-June 1994, pp. 95-101.

7 WANG Chun, op. cit., p.221.

Also see: ALVES, Leonel, Filho de Macau, in "Por caminhos solitários", Edição do Autor [Author's Edition], [n. d.][1983-?], part. 1, p. 34.

* BA in Portuguese Language and Literature by the Faculdade de Letras Universidade Clássica de Lisboa (Classic University of Lisbon), Post-graduation courses in Chinese Linguistics by the Universidade de Macau (University of Macao) and language courses by the Beijing University of Language and Culture" and the Zhongshan University, · in Guangzhou. President of the Associação de Literatura Comparada de Macau (Macao Comparative Literature Association), Macao.

start p. 5

end p.