[INTRODUCTION]

Gaspar Frutuoso [°1522-†1591] wrote the Saudades da Terra e do Ceo (Nostalgic Memories of the Earth and Heaven) during the last stage of his life between 1580 and 1591 when he was living on the Island of San Miguel in the Azores. He left the manuscript for publishing once he had died. The work itself sets out to reconstruct the history of Madeira, the Canaries and the Azores in a documental way, concentrating on the lives of naval commanders from these Atlantic archipelagos. The bestowing of the captaincy of Machico to Tristão Vaz da Veiga in 1582, led the illustrious chronicler to include an eulogy for this. Curiously enough this section of the work contains interesting references to Macao, the Portuguese settlement which Tristão Vaz would have travelled through as captain of the 'Japan voyage'. However some of these references are not backed up by any other contemporary or later source.

Could Gaspar Frutuoso have obtained an account directly from the captain who had taken up his post on 1584, years after having returned from two trips to the Far East? This is one hypothesis which perhaps merits some consideration as on the one hand Gaspar Frutuoso had amassed a considerable library with more than four hundred books. However on the other hand the handwriting of the eulogy differs somewhat from that of the author of Saudades [...] (Nostalgic Memories [...]). Besides the account of Machico's captain activities, in the part that deals with China, reveals a fleeting knowledge of Portuguese living conditions in those areas, therefore coming from certainly more than one living witness. In any case the information given in the Saudades [...] (Nostalgic Memories [...]) seems to confirm that around 1568, a little more than a decade after its founding, Macao's population had grown at a great rate thanks to the Luso-Japanese trade on the one hand, and the benevolence of the Guandongnese mandarins on the other.

19

CHAPTER XXIII

On a great victory which captain Tristan Vaz da Veiga won in China against a powerful Chinese corsair, and how he almost completed a fortress at the Port of the {Holy} Name of God, where the Portuguese were settled in China.

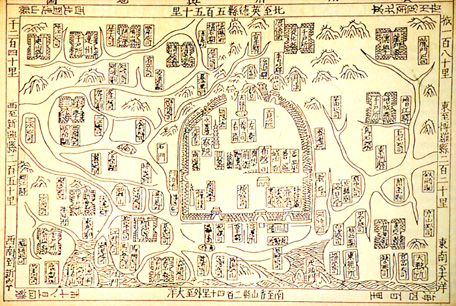

Plan of the city of Guangzhou.

ANONYMOUS Chinese.

Sixteenth century.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau - Instituto de Promoção do Comércio e do Investimento, 1966. p.42

Plan of the city of Guangzhou.

ANONYMOUS Chinese.

Sixteenth century.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau - Instituto de Promoção do Comércio e do Investimento, 1966. p.42

This captain journeyed around China where, up until then, they did not want to permit Portuguese there except for trading, and left walls erected which could very well be called a fortification. It was approved by the Chinese mandarins, who, until that time, [only] with work and bribes allowed them to even make a thatched house. And this was the situation. He arrived from Japan to the port of the Name of God, 1 where the Portuguese were settled in China, at the beginning of the year [one-thousand, five-hundred and] sixty eight, which at the time was commanded by Captain-Major Dom António de Sousa who had replaced Dom Diogo de Meneses in the 'voyage' granted to him. 2 As the customs duties had not yet been paid3 and without these one could not establish trading, he could not make ready in time to cross over to {Portuguese}** India, or Malacca, [and] he was forced to stay in China over winter.

A Chinese pirate had sailed around there for some years and from small beginnings, was now so powerful that he was the master of the seas. As there was no-one to stop him, if not the Portuguese, he decided to descend onto the settlement where they were living, and with this in mind he chose a period in which he would find fewer people there, which was [after] the Captain-Major's {ships} had left for Japan. 4 Therefore all the vessels from the previous monsoon had gone away, and those who were to come had not [yet] arrived.

On the 12th of June he appeared in front of the port {of Macao} with approximately a hundred sailing ships, among which there were more than forty very large vessels, and he came to anchor a league from the port. The next day, at dawn, he came to land [at a time when] there were less than a hundred and thirty Portuguese in the settlement, among which there were some very old and some very young {people}. [Some] of them were sent by Tristan Vaz da Veiga to his nao, which was in the port, making thirty-five of forty of them, to defend it, and he went with those remaining to confront the enemy a little way beyond the settlement, and there he waited for them to disembark5 from their vessels. And as they had distanced themselves from the ships, he fought them and thanks to God, there being three or four-thousand men, among which there were one-thousand five-hundred muskets or more, and they were so few that they did not even amount to ninety Portuguese and their servants, he won a victory over them and made them retreat back on board four times that day. They {i. e., the Portuguese} killed a lot of people and took many muskets and weapons from them {i. e., the enemy}, which had been left to make their load lighter, and they were in such a hurry that some of vessels in which they had come capsized and many drowned.

It seems like this victory was an act of God, because taking into account that on a very vast field and from very big hills, four Portuguese, who when they arrived on top could not even stand up, made so many people flee, so it did not seem like anything but God's {work}. This victory was not so easily won as thirteen or fourteen men were killed, three of them Portuguese and the others servants; they {i. e., the enemy} wounded forty or fifty from either party; for his part two shots hit him but both did little damage.

A Chinese government officer and his attendants.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, HINO, Hiroshi, Japanese trans., Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Tokyo, 1989, p. 171.

A Chinese government officer and his attendants.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, HINO, Hiroshi, Japanese trans., Tratado em que se Contam Muito por Extenso as Coisas da China, Tokyo, 1989, p. 171.

On this day the enemy were put to fright in such a way that they did not dare attack except from far away. So their captain attempted to see if he could take their {i. e., the Portuguese} nao, and fought for it for two or three days, at first with rowing boats, trying to sink it with artillery he placed in them, then with six boats, the biggest of his fleet, each chained to each other, he endeavoured to board it. However those on board defended it in such away that he {i. e., their captain} gained as little at sea as on land, and one way or other lost six hundred men, according to what was known later on. He had them like this for [about] eight days, during which Tristan Vaz was with his men in the field day and night, with enough work outside the settlement, so that they did not bum it because it was very large and spread out and the houses were made of wood and straw.

At the end of all this, the mandarins from Guangdong sent him {i. e., the captain} an appointed mediator so [that] he stopped fighting Tristan Vaz, and [the mediator ordered] him not to fight with the pirate, and that he should obey the king of China. This man sent by the mandarins went with messages from his fleet to the field, where Tristan Vaz was, and managed to make peace between them. Once it was agreed [the peace], they wrote to each other [Tristan Vaz and the Chinese pirate], and sent gifts to each other, and [this] was something which Tristan Vaz wanted, because, apart from the settlement being in great danger, the time had come for the return of those ships from the other coast, which, as they came from different areas, each one would arrived on their own, and he was afraid of seeing others taken without being able to help them.

Upon leaving this port {i. e., Macao} the pirate went around Lamao, · which was an island approximately seven or eight leagues from the Portuguese settlement, because there he was determined to meet with the Guangdongnese mandarins to make their common causes. And as a cunning corsair, he proceeded to distract them with hopes of limiting allegiance to the [Chinese] king and to do this he went on to attack Guangzhou city, which was a very fine, grand city. He plundered all the suburbs and set them on fire, taking all their {i. e., the mandarins'} fleet which they had in the river and on the shores, which were more than a hundred ships, some of them very large ones, chose the best ones and burnt those which were of no use to him, and them like this for about fifteen to twenty days.

This news reached Macao and Tristan Vaz. Together [the corsairs] said that they were to turn to the Portuguese again. It was just at this time that Dom Melchior Carneiro 6 arrived, who the King Dom Sebastião had sent as Bishop. It became apparent to everyone that they should build a fort in the settlement to defend themselves until the return of the ships from the other coast and [until] people from the countryside had been gathered together. The Bishop and Fathers of the Society of Jesus advised Tristan Vaz to order [a fort] to be built, and to give incentives to the men [so that] they would help. And as he intended that the fort they were to build would not only be a solution for their present circumstances, he ordered it to be [made] with walls of clay and mortar.

With the good command that [Tristan Vaz] had over everything, he began to put everyone to work and a lot was done in a few days. He gathered together all the Portuguese in groups of five and six, placing the wealthy with the poor and those with large families with those of small, so that they remained the same in one way or other. From these {groups} he made twenty subdivisions, giving the overseeing of each to those who appeared to be the most diligent, thus making ten subdivisions in all, much in the same way as the Christians did, and gave each one a section of wall. The Fathers of the Society of Jesus and those from St. Peter's also played their part. The competition7 between them grew in such a way than each one had their own a task and had to finish their stretch first as a matter of pride. And so without preparation of any kind, with the gateways of planks, which they had unnailed, within sixteen days they had done over two-hundred and seventy-one arm's lengths {about 2, 20 metres x 271,00} of mud and plaster wall, with six hand splays {about 0, 22 metres x 6,00} underneath and five and a half on top, and fourteen to fifteen in height.

While carrying on with the effort involved in this project, Tristan Vaz still found it necessary to confront another pirate who was plundering the coast very close to the settlement [Portuguese] with twenty three ships and which was preventing provisions reaching there. The mandarins were very insistent in asking him for help and sent some ships to the port. Tristan Vaz ordered fifty Portuguese, some Christians and some slaves to be stationed in four of them, which left Macao at dusk. At dawn they attacked the scoundrel, taking eleven of the twenty three ships along with many people and ammunitions. The [other] twelve managed to take refuge as they were faster. The gallantry of the Portuguese had been so great everywhere that a king of such a kingdom as China was not so powerful against a pirate that he could confront him without the help and favour of the Portuguese. They had experienced this so often that one of the tasks which the Chinese chief-commanders now had was to excuse themselves for asking for help so often.

There were four square in plan lookout posts around the walls and they had no time to do it any other way, with a trench on the outside, which was made of earth taken from the walls. As Tristan Vaz wanted to make a small shelter in order to finish it quickly, the circumference could not measure less than four-hundred arm's lengths {eight-hundred and eighty meters}, because of a hill which was above the port which they incorporated so it would not be exposed. Also on the other hand, it could not be too small because the settlement was growing quickly. There were many couples there too, Portuguese as well as native inhabitants, and at that time there were five thousand Christian souls in that port and they would not fit into a small place.

During the time that the pirate was there, it was a pity to see so many homeless women and children with no place to take shelter. At least Tristan Vaz had such [pity] for them, that, not being the Captain-Major, although he could have been, according to a proviso from King Dom Sebastião, while waiting for the arrival of the following Captain-Major, he abandoned his nao, which carried all his merchandise, which was no small amount, very anxious that some disaster could befall it, giving preference to safeguard the security of the settlement, for there were more valuable goods to be defended on land than those he had on board of his nao. The task was not finished until the wall was complete, out of fear that the mandarins would not approve it. {But} he had to be satisfied with completing the stretch of wall so far, because that remaining to be done was along the shoreline where each man made his pier within his access way. He resolved to force them to built them in such a manner that they would remain piers within the wall. And the wall, at that time, was made good enough to defend them {i. e., the settlement} and would very easily end up being a stronger fortification.

The situation being thus, Manuel Travassos arrived as to take the post of Captain-Major, and wanted to finish the project very much, but understood that for the time being the Guangdongnese mandarins would not take well to the fortifications being completed. Tristan Vaz felt the same way [too]; that they should refrain from [building] until there was another opportunity; and the Captain-Major waited for this. And while Tristan Vaz was still in China, it was commanded an assembly of all Portuguese, and that from [the revenues] of the ships which came to port each year, a certain percentage was to be kept back so that those walls were maintained and so there was an arsenal of gunpowder and ammunition if it were needed.

It would have pleased Our Lord that this would be the beginning of Portuguese kings coming to have many cities and fortresses in those parts {i. e., in China}. And it was extremely fortunate that it was Tristan Vaz who had began this because the first steps to a great conquest were prepared there, spiritually as well as practically, which would lead to another and without it, if it had not been for a miracle, it would have been impossible. There are many great and wealthy kingdoms of fertile and bountiful land here and with very weak and traumatised inhabitants who obey their king out of pure fear, without having any love for him.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce

For the Portuguese translation see:

SANDE, Duarte de, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Livro Segundo das Saudades da Terra, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura":, Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.130-132 & For the Portuguese modernised translation by the author of the original text, with words or expressions between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese translation, see:

[FRUTUOSO, Gaspar] RODRIGUES, João Bernardo de Oliveira, ed., Livro Segundo das Saudades da Terra, [p. n. n.], 1979, pp.167-172& Partial transcription.

NOTES

** Translator's note: Words or expressions between curly brackets occur only in the English translation.

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Gaspar Frutuoso's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, p.132.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics «" " » - unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated.

1 Tristan Vaz da Veiga [Port.: Tristão Vaz da Veiga] was captain of the 'Japan voyage' of 1567.

2 It was not uncommon for the awarded recipient of the 'China voyage' to sub-allocate the concession [or sell his rights] to someone he trusted, the more so as the 'voyage' involved considerable risks.

3 "[...] os direitos não eram ainda feitos [...]" (lit.:"[..] the rights had not yet been fulfilled [...]"): meaning, that the Chinese had still not charged the usual customs duties.

4 During its first years, Macao had a fluctuating population which changed according to the timings of the [yearly] 'Japan voyage', where many of the traders spent part of the year.

5 "alargassem" ('lit.: become distant'): meaning, 'afastassem' ("disembark").

6 Dom Melchior Carneiro, Bishop of Nicea and Apostolic Vicar in China and Japan, arrived in Macao in 1568. In spite of never having been appointed as 'Bishop of Macao', he was the first prelate to exercise these functions in the Portuguese Colony.

7 "competência" (lit.: 'concurrence'): meaning, 'competição' ("competition")

* MS., Ribeira Grande/Azores, ca 1591.

start p. 15

end p.