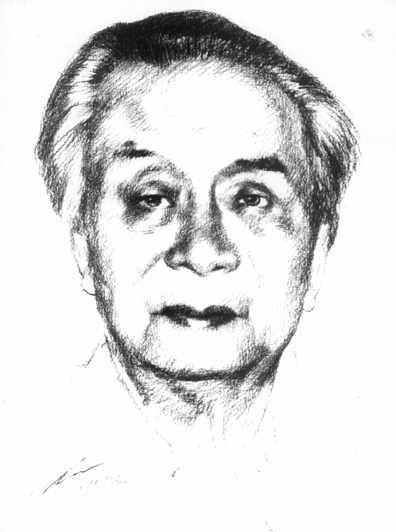

AI QING 艾青

LEI CHI NGOK 李志 X LI ZHIYUE

1996. Pencil on paper. 21.0 cm x 30.0 cm.

AI QING 艾青

LEI CHI NGOK 李志 X LI ZHIYUE

1996. Pencil on paper. 21.0 cm x 30.0 cm.

[INTRODUCTION]

I remembered that 27th March was his eighty-sixth birthday, so I sent a congratulatory telegram the day before. Who could have foreseen that on the same day he would fall ill again and lose consciousness, never again to wake up? From that day on a layer of cloud overcast my heart, for forty days in all. I wanted to pray to God that things would not turn out as I anticipated. My heart leapt whenever the phone rang, as I was terrified that it would be a call from Beijing·

But the call came through in the end. Gao Ying's• distant, wavering voice was heard on the line:

—"He is finally gone, a couple of hours ago. He said nothing, it was quite peaceful..."

I looked at my watch: it was seven o'clock, early morning on 5th May. A light mist was clearing. In the courtyard one or two roses were blooming bright red: our motherland was blessed with blue skies. But he had departed. The man who had conquered the gloom of the world with pure strength of spirit and brought blue skies to the people he loved so dearly...

§1. THE FRIENDSHIP WE SHARED IS ROOTED DEEP WITHIN MY HEART

After he had 'returned,' one of the most moving pieces of poetry he wrote was Zhi wangyou Danna zhi ling• (To the Spirit of my Late Friend Danna). I once told him how I thought about this poem. He nodded, and started to recite it very softly:

“多麽可贵又多麽艱辛——

像火災後留下的照片,

像地震後掀起的瓷碗,

像沉船露出海面和桅杆… …”

("The friendship we have at present,

How precious and yet what hardships —

A photograph left behind after a fire,

Tiles dislodged after an earthquake,

The masts of a sinking ship sticking out of the sea...")

Having recited thus far he paused and said:

—"The friendship that most commonly exists between people is like the water in a brook, trickling and burbling, but meaningless once it has flowed on downstream. It is that unspoken bond of friendship rooted in the deepest recesses of the heart which is remembered for life."

I recalled these words now, and I was so moved that my heart pounded: which variety was my friendship with him?

Seventeen years ago, as the whole nation was 'greeting the springtime of a lost generation' [the post-Mao reforms of the late 1970s], when he found out that the hardship I had suffered in my youth was linked to the political injustices he had endured, he wrote me a letter: "I would very much like to learn more about your plight and how your life is now. Can you return to Nankai daxue• (Nankai University)? What help would you need to go back there?"

During that first summer of the 1980s, as I was rewriting Ai Qing lun• About Ai Qing), I went and stayed with him for a fortnight or so in the house in Shijia hutong• (Shijia Lane) where he lived. One time I was going to see friends at the Renmin wenxue chubanshe· (People's Literature Publishers). He walked with me as far as the door of the Publishers building and was going to return home from there. I went inside and talked with my friend Yang Kuangman• (Kuangman) for half and hour and then came back out to find him round the corner to the right of the doorway, leaning against a lamp post watching the street. I was amazed:

— "What are you still doing here?"

He laughed youthfully:

—"I was afraid you might get lost, so I came back to wait for you!"

Ai Qing at the former Universidade da Ásia Oriental (University of Oriental Asia), now the Universidade de Macau (University of Macao), in Macao.

Photograph taken in 1987.

Ai Qing at the former Universidade da Ásia Oriental (University of Oriental Asia), now the Universidade de Macau (University of Macao), in Macao.

Photograph taken in 1987.

During the third summer of the same decade, I went back to the house with a copy of Ai Qing lun•(About Ai Qing), which had just been published. As we ate together in the Beiwei fandian• (Northern Restaurant), I said:

— "I feel as if my life is only just beginning." After a long silence he looked right at me and said emphatically, pausing between each word:

— "That is how it should feel your whole life!"

During the FOURTH NATIONAL WRITERS CONGRESS, ·we were both staying in the Jingxi bingguan• (Jingxi Hotel). He was on the eighth floor and I was on the ninth, so we often got together in the evenings and talked into the night. We talked about poetry, the places we had grown up in, our love lives, about my life as a cowherd and his time in exile - we talked and talked. He said earnestly:

— "We must still put our faith in Socialism. Socialism is the only way of solving our country's problems."

Ah, I almost forgot a time in late spring 1991, when I went to Beijing to attend the CREATIVE ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC COLLOQUIUM.• I arrived in the evening of the first day, so it was not until the afternoon of the second day that I went to East 43rd Street to see him. He was having great difficulty walking, and limped up to greet me when he saw me. Straight away he asked me:

— "When did you arrive?"

When he learned that I had been in the capital for nearly a day, he was displeased, and said:

— "So why did not you come over yesterday?"

I did not have time to explain the whole story in detail before he said:

— "You will stay here tonight then!"

He would not take no for an answer.

I also cannot forget a time at the end of May 1992, when he returned to his home town of Jinhua• for the second time in ten years. I stayed with his family for three days. On the fourth day I wanted to make a hasty departure for Hangzhou· to preside over the defence of a Master's degree dissertation at the University. Very early in the morning, I went to say goodbye to him. He said:

— "No - you must stay here!"

With these words he tugged at my hand and had me sit down next to him. Not saying a word, first one minute passed, then another... I was not going to be able to get away that morning, clearly. When I tried again after lunch to say my farewells, his face suddenly flushed red and he shoved my shoulder and blurted out:

— "You are going then? So go!"

It is said that poets have fiery temperaments. Maybe on that occasion he had predicted that this was our final farewell.

Even more memorable is May 1993, when he heard that my wife Chen Ruiying• and I had published a joint collection of poetry entitled Yidian yuan• (Yidian Garden). With his trembling hands he wrote a Preface for it in spidery handwriting, in which he referred to his friendship with me. "Hanchao's relationship with me has had its ups and downs. He began to study my writing back in the 1950s when he was a university student, and graduated with a dissertation nearly twenty thousand words long. Unfortunately he was branded a Rightist in 1957, when it was that same dissertation which finally condemned him. After his rehabilitation in 1979, he picked up his study of my works where he had left off. It was this undertaking and general good fortune which brought us together as friends."

These unfading memories now seem dreamlike in quality, but they are all memories of real events. Looking out at the courtyard bathed in sunshine, the green grass and the fresh flowers brings to mind May 1982. When he first went back to his home town after returning from exile, we went for a long walk by Xizihu. (Xizi Lake). We talked of our love for the seasons. I said:

— "May is my favourite: "The first month of summer swells with the luxuriance of every tree and flower." It is such an invigorating and life-affirming season."

He suddenly asked:

— "Which sorts of sentences do you like best in my writing?"

— "We should be thankful for life, because of all the significant things we can do while we are alive," I quoted.

He laughed like a child, quite uninhibited. I can still see him laughing today - the expansive laughter of a true kindred spirit. At the same time I am aware that between the two of us, close friends despite a great difference in age, was forged a friendship rooted deep within our hearts.

Ai Qing at the former Universidade da Asia Oriental (University of Oriental Asia), now the Universidade de Macau (University of Macao), in Macao.

Photograph taken in 1987.

Ai Qing at the former Universidade da Asia Oriental (University of Oriental Asia), now the Universidade de Macau (University of Macao), in Macao.

Photograph taken in 1987.

§2. HIS GREAT LOVE FOR THE SUN AND LIFE'S VERDURE

That time when I stayed at his house in Shijia Lane, I helped him edit a draft transcript of a recording of him talking at the Qingchun shi hui· (YOUTH POETRY CONVENTION) hosted by "Shikan"• ("Poetry Magazine"). It was later published under the title Yu qingnian shiren tan shi• (Talking Poetry with Young Poets). The day after I had been entrusted with this task, I got up at dawn, switched on the light and set about editing it. Suddenly I saw someone's shadow passing outside the window and going out into the yard. I did not think of it at first, but then I remembered his habit of getting up early to write, but surely this could not be him? I pushed open the door and went outside. A tall man was standing in one corner of the yard by the gourd plant enclosure - it turned out to be him, absorbed with full concentration on enjoying the flowers just appearing on the gourd plants. I walked over and said softly:

— "Are you looking for inspiration?"

He looked round at me and with a dreamlike look in his eyes said:

— "Look how beautifully they are shaped. The stamens in the centre, with the petals set harmoniously around the outside, all symmetrical, all perfectly arranged. Who was the architect? Life itself!" Just at that moment a butterfly happened to fly by and penetrate the stamens. He said with a chuckle:

— "It is love - the butterfly loves the flower!" Looking around, he pointed at a pile of coal and the broken stones from the rockery fired his imagination: "Perhaps the coal is thinking of the thickly forested slopes of Changbaishan• (Changbai Mountain), and the rockery is reminiscing about Taihu• (Tai Lake). There is life everywhere in this place."

— "Is that how you came to write Mei de duihua• (Coal Conversation), Jiaoshi• (Rocks) and Yu huashi• (Fish Fossil), from these morning pilgrimages in search of inspiration?"

—"You are quite right!"

He patted me on the shoulder, and pointed towards the gate:

—"Let's go and take a look at the early-risers!"

He led me out of the gate. As he walked, he called over to me the following profundity:

— "To love poetry is to love living, and to love living means to love life itself!"

He marched out with brisk strides.

Thinking back, I cannot help feeling sad. I never again saw him stride with the same vigour; now his tall, imposing shadow has vanished forever. Yet those words: "To love poetry is to love living, and to love loving means to love life itself," are perpetually reverberating in my heart. The contacts I had with him after that, his various perspectives on life, history and poetry all made me relate even more to those words.

Another memory from that time in May 1982 when we were strolling around Xizi Lake chatting was a conversation about the life force of the seasons. this conversation played a key role in the forging of our friendship. I said:

—"Your creativity has peaked twice. Once was in the late 1930 and early 1940s, typified by Xiang taiyang• (Towards the Sun); and then again in the late 1970s and early 1980s, which is best represented by Guang de zange• (Song in Praise of Light). You could liken these two peaks in creativity to two seasons rich in life force."

He pondered this for a moment and then said:

— "You cannot give me the credit for that; it is part of what it means to be Chinese, part of our era. One event was the kang Ri zhanzheng• (War of Resistance Against Japan), when the whole nation rose on a wave of patriotic fighting spirit; the other was the gaige kaifang• (Open Door Policy), which spread democratic fervour throughout the whole country. Of course, it could still be claimed that these two periods were just times in my career as a writer when external life forces peaked."

— "But I still maintain that since it was this era brimming with life force which wrought the great poet in you, it was you who pioneered this period of poetry rich in life force -I do not expect you to agree with the second half of that, by the way!"

—"Quite so!"

— "At the very least, it is clear that these two peak periods and a few of your key works are all concerned with a passionate craving for the sun and the green of plants, which reflects how much you love the light and growth. You must agree with that!"

He laughed and joked:

— "You really know how to stick the barbs in!"

After this he sank once more into thoughtfulness:

— "It is true that I do love the sun. I have written plenty of poems singing the praises of the sun. Because the way I see it, it is a poet's job to give people the courage to aim for ideals, and we always see the sun as the symbol for optimism and idealism - and of course it is the sun which is the source of all life, which is something I laid particular emphasis on in Guan de zange (Song in Praise of Light.)"

— "It boils down to the fact that love for life is the starting point of the quest for beauty in your poetry. Because you love life, you eulogise the sun and praise green things. How often does the phrase "life's verdure" occur in your poetry?"

As we talked about these things, we had reached the stretch of road between Zhaoqing si• (Zhaoqing Temple) and Duan qiao• (Duan Bridge). On either side of the road there are unusually tall parasol trees, bushy with leaves of a deep green hue which hang over the road and embrace it with a thick canopy. Setting out along this stretch of road it seemed as if there was a sky of green foliage. He seemed to have become rather excited, and muttered:

— "This green is so lovely! I have not been to Hangzhou• for years, and this time I find it greener than ever. Look at these parasol trees, the lotus leaves on the lake, the open lawns on this side and the willows over there by the embankment. It is all one wide swathe of green. Hangzhou seems to be living through a season particularly rich in life force."

— "Did not coming to Guangzhou• leave you with the same impression? That was why you wrote the poem Lüse• (Green):

“刮的風是綠的,

下的雨是綠的,

流的水是綠的,

陽光也是綠的。”

("The wind blows green,

The rain falls green,

The water flows green,

The sun shines green.")

And it prompted some people to accuse you of writing vague poetry. They said they could not understand it!"

— "Right. I have travelled to many places in the last few years, and it always seems that our country grows greener and greener; the verdure spreads to their hearts too. It really seems as if the era rich in life force you mentioned has really returned. And if people criticise, then it is because they..."

— "If they do not understand how to live life or how to enjoy living, then they're also unable to understand poems like Lüse (Green), are they?" He patted me on the shoulder again and chuckled:

— "Your logic's got holes in it."

§3. SINGING WHILE BEARING THE CROSS OF HUMAN FATE

Reminiscence is always painful, but it also makes me think more deeply about him.

During the two months which have passed since he left this world, I have got up early almost every day to read his works. Most recently I have been reading Shilun• (On Poetry), which he wrote fifty-seven years ago. I have read it many times before, but just now I have been reading it afresh, and it seems unlike the book of theory it is, but more like a long lyrical poem. He delivers a clever monologue to the world facing him. I read for the third time the third section of the piece entitled Fuyi· (Enlistment): "Do not make empty predictions about human fate, do not use the tone of the prophet: 'Come with me, all of you!' Position yourself instead amongst the people who are looking for a road to follow: breathe with them, share their joys, their sorrows and their thoughts; live and die with them. Only then will you be able to fashion your words into an authentically human cry."

These words acted as a magnet which drew out all my deepest memories. I had a true sense of this poet who loved life, enjoyed living it and encapsulated these ideas in his poetry. It was as if his spirit was bearing the cross of human fate.

I also want to mention a time in 1980 in Shijia Lane, and describe the circumstances under which I first met him there. I went to his house at noon on the 1st of August. Gao Ying had prepared a sumptuous lunch to welcome me. I do not drink, but on this occasion I broke my rule and drank a toast with this trusted pair of friends. After the meal we took time to sit down to talk. We talked about the prospect of combining the living room, the reception room and the writing room into a single, long, allpurpose room. I was sitting on a sofa which was placed along the east wall; he was sitting on an armchair in front of the desk, casually but fondly touching with one hand the big pile of journals and papers on the desk, some of them old, some not so old, in various languages. A blazing sun shimmered beyond the blue curtains at the western window, while the inside of the room seemed peculiarly serene and calm. We talked for two hours or more in this room, where the atmosphere was racing with his inspiration. He began to talk of the times when he suffered, and how people from all over the country and all over the world started to inquire into his whereabouts because they were concerned by what might have happened to him. Suddenly I felt a dazzling brightness before my eyes. The fierce rays of the sun burst into the room. He pulled the curtain open and looked fixedly out at the television aerial which had been amateurishly fitted to the withered trees outside. A sense of solemnity welled up inside me, as if the combined sounds of the whole world calling him were converging in this study. Most resonant was the call of the mine workers: "We have been searching for you for twenty years, we have been waiting for you for twenty long years [...]." Suddenly he turned round, slapped his hand down on the pile of books and papers on the table, and said urgently:

— "I am just an ordinary man who writes poetry, no different from a worker who operates machinery or a farmer who works the land. So why did so many people in the world care for me so much, and seek me out when I was faced with difficult times?"

He paused for a while, and his voice softened again, almost as if he was talking to himself:

— "When I think about how many people in the world placed their trust in me, and remembered me as if I were their own family, longing for me to sing out for the fate of humankind, to take up the cross once more: how could I hesitate even for a moment?!

Once again I was moved, reminded of Antaeus in Greek mythology. With no regard for the customary discretion usually required when meeting people for the first time, I gushed forth, uninhibited:

— "When Antaeus was united with the earth, he was endowed with incredible strength. In your case, the 'earth' is the human race you have spent your life singing out for. In the same way, your feelings belong to a world which remains steadfastly optimistic in the face of hopeless dread. Just as you celebrated that pile of coal in the yard, you are still able to smile when you look out to sea, even though its waves battered you until black and blue. You are not a poet obsessed with grief. But in Zhi wangyou Danna zhi ling• (To the Spirit of my Late Friend Danna), you say that the sound of your own poetry 'also contains the bitterness of grief even in its most joyous moments,' so it seems that you are a poet who dwells on grief after all. Why is this?"

He took out a cigarette and lit it, and sat back down in the armchair. He handed me a copy of a poem Chensi• (Contemplation), which he had written the year before. He smiled with his eyes and said:

—"Last year, when I was on the train from Guangzhou to Shanghai, I looked at the rice paddies on either side of the railway track and the workers labouring on in spite of the rain. I speculated on the tacit agreement which must exist between these people and the earth they worked. Their bounteous harvest was assured, and their lot was bound to improve, but I was still unconvinced. A wave of melancholy engulfed my heart, and I had to write a poem. You asked me 'why?'; I ask the same question 'why?' many more times in the poem. Maybe I am asking myself: "Why... Why... is my heart still so full of melancholy?" To be honest, I have never in my life known true happiness — only sorrow."

At the time I was soothed by his deep, dulcet tones and by everything that his words implied. For a moment I was unable to speak. I just looked at him in silence; he looked back at me, also silent. I have no idea how much time passed in dialogue without words, but then came the question of how to bring our communication to some conclusion. Thinking back now, the topic of our conversation was extremely important, but I had not realised this at the time. It was not until May 1995, when he returned once again to his home town and I heard him telling a story at a banquet, that I fully comprehended the extent of the insight into the realm of his emotions which our conversation that year had given me. The story he told was prompted by the table laden with fine foods which greeted him.

He said:

— "All this fabulous food! The old homeland has really prospered. But let me tell you all a story. There was once a peasant who lived in hard times - times are always hard for peasants! He died, and was summoned to heaven by God, who said to him:

— "You suffered all you could when you were alive; now you have arrived in heaven, you will be given everything you desire: just say the word!" The peasant thought hard for some time and then replied:

— "I want dumplings!"

I was severely shaken by this. It was clear that he was constantly aware of the plight and sorrow of the people. Of all people, it was the peasants who suffered the most. This was why the the thought of peasants suffering which had affected him since his early years went on to forge feelings buried deep in his heart. Even though, like Antaeus, he was forever bonded to the earth, joyful, firm and fearless in his resolve to sing out for the future of humankind. Except that whenever he felt that the fate of humankind was not changing for the better, he was unable to disassociate himself from the suffering peasant he felt in his heart. So in the end I understood: he was bearing the cross of the fate of humankind, singing his way through life to the end of his days.

§4. A FIGURE ESTABLISHED ON THE BASIS OF AN AMALGAM OF DIVERSE CULTURAL INTERACTION

People have said that he was proud, that he was sarcastic. I can find no way to reconcile these criticisms with the facts of his life. His South-Eastern Chinese temperament made him extremely surly at times, but in fact he instinctively showed respect for other people, always initially seeing people in their best light. I have seen him lose his temper quite shamelessly and cause people acute embarassment, but then later go and pat the same person on the back and say:

—"Do not be angry!" This is indicative of an inherently modest and unassuming outlook on life. It made him uniquely able to adopt an affirmative stance with in his dealings with people in the literary world. Once we were talking about the Jiuye shipai• (Nine Leaves Poetry Group). He made the positive comment:

— "That woman Chen Jingrong• is a genius." On another occasion, as we talked about Tian Jian•, he said:

— "When some people write poetry, they have no grasp of imagery. Tian Jian is wonderful, he can really feel it. This is how he wrote of Lu Xun's• death:

“呼喊著,

呼喊著。

走近10月的,

河邊,

他停息了。”

("Shouting, Shouting. As he approached the October river bank, He stopped, It is so full of life, solid and profound.")

One time we were discussing Dai Wangshu• with Jiang Yunfei•, a researcher from Zhejiang shifan daxue· (Zhejiang Teacher Training University). He said:

— "This poet has something to contribute. The body of his poetic writings is not large in volume, but it is pithy and moving. You always say that I favour the use of everyday spoken language in poetry — well the credit for that should go to Dai Wangshu, since it was he who first had the idea. I simply took it up from there."

It was attitudes and views such as these which made his poetic soul like a sponge soaking up water. He was adept at feeding on various kinds of poetic 'nutrition' to build up his own poetic frameworks. Perhaps it was exposure to diverse cultural associations which completed him. He became a decisive component in a generation of great poets.

The day before the opening of the FOURTH NATIONAL WRITERS CONGRESS, I was with Xin Di,• Tang Shi· and some other leading poets. Along with my friend and contemporary Li Yuanhai,• we all went to pay him a visit at his new home in Fengshou hutong· (Fengshou Lane). Everyone talked excitedly in his living room. Gao Ying was running round in circles looking after us, and she was made busier still by the fact that she too loved to talk. Suddenly he said:

—"Hart Chao has written an article about me. He told me it was called Striding Into the World of Poetry Wearing Shackles, a very vivid image, rousingly effective. But the truth is that I was not shackled. In fact, I entered a Guomindang· (Kuomintang) prison carrying a volume of poetry and emerged from it into the world of poetry."

He meant nothing special by this remark, but his audience listened with glee. I for one was following his every word with rapt attention, pondering the diverse patterns and structures of his poetry. He once talked with me about the question of influences in writing. I suggested that ones mode of thinking itself was one aspect of the arrangement of ideas which was subject to influence from other sources. He was very much in agreement, saying:

— "These days, a broad variety of world culture is available for the whole planet to share, so influence should also be global in nature. When it comes to the specific source of that influence, the corpus of another writer's work, or one book, one passage or even one sentence can exert the crucial influence."

— "So that is why [Fanerhalun] was your springboard into the poetic world!"

—"Exactly. I like [Fanerhalun]'s poetry very much. I actually translated one collection of poetry into Chinese while I was in prison: The Country and the City. The lyrical perspective and imagery have influenced me all my life. I have also been influenced by Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Whitman, Mayakovsky and Sandburg at one time or another. I remember one sentence in a poem by Rimbaud, a description of the sound of church bells ringing. He wrote: "The purple sound of the bells." Sandburg described the fog in an American harbour as having arrived "[...] like a cat stalking on tiptoe [...] arching its back, the settling down to watch the harbour and the city, not about to leave." These things all influenced me."

—"But in Dayan he — wo de baomu•(My Nanny the River Dayan), you describe the Dayan River as "the purple spirit." In your epic poem Kuimie, wu• (Crumbling Collapse & Fog), the fog is likened to an old person with long loose silvery grey hair, barefoot, leaning on a stick, clambering effortfully out of the wet swampland and wandering directionless. These images seem far more evocative, inspired by deeper feeling than those other writers!"

—"Those two examples might give people reason to think I was lifting ideas from them verbatim, though they are both purely coincidental. My original intention was to make use of the influence their thinking had on me, the approach of novel associations and innovative imagery. For instance, I read Li He's• poetry, and while I have forgotten everything else, there is one sentence which sticks in my mind. It is about a beautiful woman rising early and sitting down at her dressing table to put on her make up. She carelessly drops a hairpin on her naked leg, which the poet recounts thus: "The jade hairpin fell, making no sound." The word Li uses for "no sound" is quite exquisite. In this case it could be said that a single sentence had an effect on me. It enabled me to develop the imagery in my work more deeply. There is enough to sustain a whole lifetime of work."

Listening to him talk, I suddenly saw the light. Without waiting for him to finish what he was saying, I interrupted:

— "No wonder the blazing flame in your long poem Huoba• (Torch) is described as "[...] shattering the night [...] smashing the night piece by piece." The association in this perhaps owes something to the influence of that line of Tang• poetry: "[...] black clouds weigh down the city to the point of collapse"?"

Once again he patted me warmly on the shoulder and said:

— "You are very sharp! People who write poetry must want to achieve, they must want to assert artistic authority and express their personality. They must be receptive to a wide range of stimuli, not restricted by nationality or race. We must all cherish and make use of the common cultural wealth of humanity; we can apply our own assessments to this wealth and transcend it. Good examples of this are Neruda, a Nobel Laureate, and [Xikemeite], who was imprisoned for many years for revolutionary activity. They are friends of mine, and I like their poetry very much. Neruda's writing is expansive, [Xikemeite]'s is deep and brooding. Apparently one night some time in 1957, Neruda called my name as he stood by the sea in Chile, facing out to the Atlantic Ocean. I do not know if this story is true or invented, but our friendship is definitely real. [Xikemeite]'s epic poem [Zhuoya] is better than mine. He writes about [Zhuoya]'s throat, saying that a necklace, a gift from her lover, should be hung round it; it should not be harnessed with a rope. His writing is very moving and profound - an extraordinary example of poetry which I cannot compete with. But I am who I am, and they are who they are. Their special talents provide me with inspiration, so it is worth my while to study them for my own personal use. A measure of egocentrism is permissible in this instance; in fact it is obligatory, so do not criticise me for it."

We looked at each other and laughed. Yes, he is a great poet who built himself up from the basis of an amalgam of diverse cultural interaction.

CONCLUDING EPITAPH

The scenes from these recollections and illusions have flitted one by one across the screen of my memory. Is the final scene to be of a figure lying in serene sleep amongst fresh funereal bouquets, with both wise eyes closed? It has to be accepted that he has left us for good. But at the same time I refuse to accept it. I want to take hold of him and say:

— "Do not leave! Can't you wait a while? I have not yet finished relying on you yet."

I will never forget him saying to me on two occasions:

— "Your study of my poetry has made you suffer as I did, though the situation has improved now. I have one request: could you have through my writing and find out for me the thread which runs through all my work?"

Ten years flew by after that request. How much water flowed under the bridge during that time, as I read his poems and wrote research articles about him. I have already written a portion of the three hundred thousand words of criticism and biography, commissioned by Chongqing chubanshe· (Chongqing Publishers). That common thread could turn up at any moment, but he will not be around to learn what it is. He slipped away quietly...

At present, writing Shilun• (On Poetry) is at the top of the agenda, and the third section of Fuyi (Enlistment) is still in my sights. Visions of past events are constantly flashing through my memory anew. I have bursts of inspiration: it feels as if I am pushing open a door into a holy place, enabling me suddenly to see that line stretching and winding back to the beginning of the century, enshrouded in a pall of gun smoke. On both sides of the line are countless millions of people brandishing shovels, shouting and surging forward. But on the line, there is one individual who is keeping up stride for stride with the thronging people. This person is Ai Qing. He placed himself in the midst of humans seeking a road to follow. He adds his voice to their call, shares their joys and sorrows, lives and dies with them. He sounds his bugle as he walks along.

The sound of his horn echoes far and away, carrying with it his very life blood. In the far reaches of the wilderness is an inscription in many languages:

"Ai Qing — Great Poet of the Twentieth Century."

Written during the afternoon of 23rd July 1996 at Shishan, Xizi Lake Peninsula, Hangzhou.

Translated from the Chinese by Justin Watkins

* Professor in the Department of Chinese at Zhejiang University.•

start p. 137

end p.