"That name of Orient is one that sounds to me as a treasure. So that such A name may produce in someone's spirit its full and total effect it is necessary, first of all, never to have been in the vague region it determines [...]. So is the essence of a good subject of dreams."

Paul Valéry

§1. ORIENTALISM IN BRAZIL

The analysis of Chinese, Japanese, Indian and Moorish elements within the repertoire of Brazilian Baroque still remains an unexplored thematic source by Art History researchers.

The following is a succint listing of 'Oriental' motifs in Baroque buildings and monuments which lay beyond the borders of Brazil. In Mexico: the towers of the Mother Church of Tasco (near Acapulco), a frieze with dragons and pelicans in the Convent at Coixtlahuaca, the Indu figurations on the pulpit of the Mother Church of Huaquechula, and the 'Chinese stage' in the Cathedral of Guadalajara; in Peru: an overdoor with a sculpted elephant in the Colégio Jesuítico (Jesuit College) of Ayacucho; in Colombia: the High Altar with pheasants and elephants in the Church of San Francisco (Saint Francis) in Bogota; in Equador: the panel with a divinity in a vedic pose flanked by sea dragons in the Chapel of San Javier (Saint Xavier) in Nazca; etc. 1

Taking in consideration the vastness of the territory, it is noticeable that the scattered examples of this repertoire which exist in Brazil are confined to a geographically defined area. Gilberto Freire may be mentioned as the leading authority amongst the scholars who contributed towards the survey of 'Orientalism' in Brazilian culture. He explicited the facets of that genre in the Brazilian lifestyle, environment and culture. For this author "what may be ascertained is that by the late eighteenth and early nineteen centuries, in the entire American continent there were traces of such integral adaptation as in Brazil of elements such as the women's shawl, the ladies' turban, the palanquin, the esteira (mat), the quitanda (stall, exp1.: fruit and vegetables stand, small grocery store) the bangüê (handbarrow), fireworks, the rótula or gelosia (lattice-work shutter), the concave roof-tile, the corner tile shaped like upright cornos de lua (moon crescents), the azulejo (glazed tiles), the whitewashed house or brightly painted outdoor elevations, structures shaped as pagodas, the chafariz (drinking fountain), the Indian coconut and mango tree, the elephantiasis of the Arabs, the cuscus, the alfenim (exp1.: a kind of sweetmeat), the arrozdoce (exp1.: a dessert made with rice and sugar), cloves from the Molucas, cinnamon from Ceylon, pepper from Cochin, nutmeg from Banten, tea, textiles, porcelain and ceramics from China and India, perfumes from the Orient, [...]."2

Scattered in the North-Eastern Brazil, where colonization started early in the sixteenth century, one can still find several unspoilt examples of 'Orientalisms', the best preserved of all being a wardrobe with chinoiseries, in the Church of the Ordem Terceira do Carmo (Third Order of the Carmo), in Cachoeira, near Bahia. This wardrobe's internal and external decorations are pictorial panels representing brightly coloured human figures surrounded by trees, flowers and birds, on a pale continuous background.

The region of Minas Gerais is rich in 'Oriental' examples, particularly those derived from Chinese art. This article makes particular reference to the 'Orientalism' in Minas, as it specifically developed in the context of the evolution of the Baroque in this region.

Early travellers were quick to notice similarities in the architecture of certain constructions in the region of Minas Gerais and that of China. In the nineteenth century, Richard Burton3 described the similarities between the trussing of local Colonial roof structures and Chinese building techniques, the major difference being -- according to the chronicler -- that the latter were made of bamboo.

More recently Eugénie M. Brajnikov compared the vernacular eighteenth century architecture of Minas to Chinese architecture. The author remarked that the roofs' curved eaves of the old houses in Sabará,Mariana and Caeté were equally characteristic to Far Eastern construction typologies. The author also put forward the hypothesis that the reason for these architectural similarities most probably derived from the influence of the religious Orders on local Christian architecture. According to her, the Franciscans and the Jesuits were the main catalyzers for the import of 'Oriental' motifs into Brazil. 4 This hypothesis is difficult to articulate specifically in Minas were a Royal Law strickly forbade the Clergy and monastic Orders to settle in the region of Minas Gerais, the secular communities having to rely on Brotherhoods, Confraternities and Third Orders for spiritual support5. Transfers of motifs from Asia to Brazil must therefore have been alternatively effected.

Further similarities can also be observed. The broken pediments of some Churches and Chapels resemble the architecture of Chinese pagodas. Examples of this are to be found in the Churches of Sta. Rita, in Serro; of the Mercês (Mercy) and the Archconfraternity dos Anjos (of the Angels), in Mariana; of the Rosário (Rosary), Itabira, Sta. Bárbara (St. Barbara) and São Francisco (St. Francis), in Caeté; and in the Chapel of the Nossa Senhora do Ó (Our Lady of O), in Sabará.

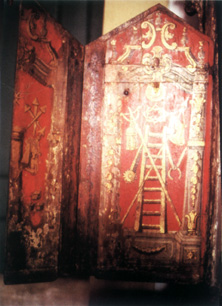

Oratory.

Eighteenth century.

Woodcarved and gilt. Museum of the Inconfidência [i. e.: related to popular movement 'Inconfidência Mineira'], Ouro Preto.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Oratory.

Eighteenth century.

Woodcarved and gilt. Museum of the Inconfidência [i. e.: related to popular movement 'Inconfidência Mineira'], Ouro Preto.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

In sculpture, there are less comparative examples. Equally important in content, but in a smaller scale, are a number of examples of religious statuary which exhibited so-called 'turquices' (expl.: from Turkey) a term which expresses the Arabian rendering of the figurines' racial affinities and exotic fashions. Such characteristics are found in the statuary in the forecourt of the Sanctuary of the Bom Jesus de Matosinhos (Good Lord of Matosinhos), in Congonhas do Campo, by António Francisco Lisboa, popularly known as o Aleijadinho (the Crippled). Robert Smith explains this genre deriving from a Medieval tradition in which all Biblical protagonists and Christian hagiography representations were to be rendered with capes, berets and turbans according to coeval Moorish fashions.

The Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archdiocese of Mariana) has a unique statue of St. Cecilia with a strong Chinese facial expression, hair style and garnments. This patron-Saint of musicians and Music ensembles was widely worshipped in Minas during the Colonial times, due. to the prolific musical activity of the region.

During the Baroque era, the Fine-Arts contacts between Brazil and the Far-East were best and most abundantly expressed in painting. Chinoiserie or 'chinesice'6 painting became popular, particularly in the religious context. Amongst the many examples in Minas are worth mentioning the following: the Sacristy doors and altar structure of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament) in the Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), and the seven surrounding panels of the High Altar in the Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó, both in Sabará; the Sacristy ceiling of the Chapel of the Soledade (Nostalgia), the organ and the twenty panels of backrests of the stalls of the Chancel of the Sé (Cathedral), and the windscreen in the Church of the Ordem Terceira do Carmo, all in Mariana; the niches of the side altars of the Mother Church, in Catas Altas; and the High Chapel in the Mother Church in Cachoeira do Campo.

These pictorial representations attest a variety of materials and techniques, such as the use of lacquer -- already greatly in vogue in Europe, during the seventeenth century7 -- and the appropriation of favourite themes in Chinese figurative painting, such as 'flowers and birds',8 pagodas, landscapes, vegetation (mulberry bushes, cherry trees, bamboos, and others) and animals. Also noticeable is the repetition of pictorial representations in gold on a red or blue monochrome background.

Interior of the chinoiserie panel of the oratory door -- detail.

Eighteenth century.

Symbols of the Passion framed by an architecturally scenographic arcade in gold paint highlighted in black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer vermillion monochrome background.

Museum of the Inconfidência [i. e.: related to the popular movement 'Inconfidência

Mineira'], Ouro Preto. Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Interior of the chinoiserie panel of the oratory door -- detail.

Eighteenth century.

Symbols of the Passion framed by an architecturally scenographic arcade in gold paint highlighted in black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer vermillion monochrome background.

Museum of the Inconfidência [i. e.: related to the popular movement 'Inconfidência

Mineira'], Ouro Preto. Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

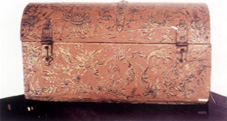

Ballot-box.

Eighteenth century. 'Flower and bird' composition in gold paint highlighted with black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer cinnabar monochrome background. Woodcarved and gilt.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Ballot-box.

Eighteenth century. 'Flower and bird' composition in gold paint highlighted with black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer cinnabar monochrome background. Woodcarved and gilt.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Statuette of Saint Cecilia.

Eighteenth century.

Polychromatic carved wood.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana).

Mariana. Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Statuette of Saint Cecilia.

Eighteenth century.

Polychromatic carved wood.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana).

Mariana. Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Ballot-box.

Eighteenth century.

'Flower and bird' composition in gold paint highlighted with black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer cinnabar monochrome background.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Ballot-box.

Eighteenth century.

'Flower and bird' composition in gold paint highlighted with black contours over a patinated imitation lacquer cinnabar monochrome background.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Statuette of Saint Cecilia --head detail.

Eighteenth century.

Polychromatic carved wood.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Statuette of Saint Cecilia --head detail.

Eighteenth century.

Polychromatic carved wood.

Museu Arquidiocesano de Mariana (Museum of the Archidiocese of Mariana), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

It is interesting to note that most of the pictorial chinoiseries occur in Churches built during the first half of the eighteenth century, most of them being Mother Churches. It is therefore possible to infer that this pictorial genre was considered as a refined contemporary type of decoration. Despite these pictorial figurations being in predominantly religious places and surrounded by images of Christian iconography, they clearly express profane themes. Neither are the subjects of these chinoiseries metaphorical or restricted to allegories, rather-- we feel --they are 'instruments' of Baroque artifice, expressions of the synthesis' efforts of this period of Art 'plastic Language'. According to Lourival G. Machado "they[the chinoiserie paintings] are only to be understood on decorative terms devoid of symbolical meanings, 9 thus aiming at an effect of "singularidade ornamental" ("ornamental singularity"). 10 Whatever their interpretation may be it should be emphasised that profane subjects in paintings are not a Baroque invention, but that the Baroque was the catalyser in the promotion of the "desacralization"11 of profane subjects within the Christian religious realms.

Façade.

Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença

Façade.

Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença

The 'porta de Macau' ('door of Macao'), in the Evangile side of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento.

Eighteenth century.

The 'old' door giving access to the Sacristy of the Church. Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament) in the Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The 'porta de Macau' ('door of Macao'), in the Evangile side of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento.

Eighteenth century.

The 'old' door giving access to the Sacristy of the Church. Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament) in the Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The High Altar seen from the nave.

The frameworks of 'old' door giving access to the Sacristy and the 'new' blind door -- symmetrically opposite -- are partially visible on the lateral walls of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament), respectively, on the right and on the left. Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The High Altar seen from the nave.

The frameworks of 'old' door giving access to the Sacristy and the 'new' blind door -- symmetrically opposite -- are partially visible on the lateral walls of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament), respectively, on the right and on the left. Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The 'porta de Macau' ('door of Macao') replica, in the Epistle side of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento.

Probably nineteeth century. The 'new' blind door symmetrically positioned opposite the 'old' real 'porta de Macau'('door of Macao'). Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament)in the Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception). Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The 'porta de Macau' ('door of Macao') replica, in the Epistle side of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento.

Probably nineteeth century. The 'new' blind door symmetrically positioned opposite the 'old' real 'porta de Macau'('door of Macao'). Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento (Most Holy Sacrament)in the Mother Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Our Lady of Conception). Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The iconographic analysis of these pictorial representations attest a repetitiveness in the composition of the figurations. For example, in the panels of the backrests of the Chancel of the Sé, in Mariana, there is a predominance of human figures, animals, birds, butterflies and architectural structures, and in a much smaller number, travel vehicules. Out of the twenty panels, fifteen depict hunting scenes. By the way in which several human figures appear alternately in a number of panels is clear that the artist worked with an originally reduced number of models assembling them in multiple positions within the overall composition of each panel. For instance; the hunters which are depicted in the second panel on the right are reproduced in the sixth, seventh and eighth panel also on the right. The 'Oriental' painted decoration in the Chapel of the Nossa Senhora do Ó, in Sabará, complies with a similar layout. Its seven octogonal panels are conceived from four basic shapes. The artist symmetrically displayed six larger panels crowned by the seventh, which is smaller and fits with the crux of the arch of the transept. Furthermore, the six lower panels are paired, respectively representing pagodas and birds. All the pictorial representations are devoid of volume, expressing a flattened composition solely animated by the suggested movement of the flying birds.

The paintings in the Sacristy of the Chapel of the Soledade, in Sabará, basically display configurations of flowers and birds painted in joyfull colours over a white ground evocative of the most graceful examples of Europen Rococo. The paintings in the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento of the Mother Church, in Sabará, are devoid of figuration, merely depicting pagodas and a variety of architectural structures. The original Sacristy door (the darkest and most damaged of the two) in this same Church was the prototype of another in the same location. Presently, they symmetrically flank the lateral elevations of the Church's Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento with the difference that the late copy is now a a blind door.

The aesthetic analysis of these works of art is now a virtually impossible task due to their past non-existent preservation conditions. Another factor is the lack of documentation such as the Church's log books, income records, expenditure logers, etc., apparently lost in a fire. A rare available register is a detailed drawing of the original door of the Sacristy notated by Eugénie Brajnikov, around 1950. Brajnikov12 noted that the depicted subject is the same as in namban screen art, 13 were European missionaries and traders were portrayed by the Japanese artists. It so happens that some of the elements of this composition bear strong resemblance to a number of motifs of the panels of the backpanels of the stalls of the Chancel of the Sé, in Mariana, particularly the human figures amongst the pagodas, the trees and the birds.

Popular oral tradition narrate that the 'porta de Macau'('door of Macao') of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento of the Mother Church, in Sabará, was given by a Portuguese King -- possibly Dom João V, who was the donor of the organ of the Sé, in Mariana, according to written documentation.

One of the key questions which has especially animated the debate of the researchers on the subject of 'Orientalism' in Brazil, is to establish the source of such imagery, mainly by defining a criterious aesthetic judgement for their manufacture. Regarding the production of some paintings it has been already possible to structure attributions' hypothesis. During the first half of the eighteenth century the painter Jacinto Ribeiro lived in Mariana. This is registered in the Livro de termos de amoestaçóes as follows: "[...] to this Borough of Nossa Sra. da Conceição dos Camargos came Jacinto Ribeiro, bachelor, who survives by his art of painting, natural from India and now resident in the area of this Borough of an age which he declared being thirty eight years to be admonished."14

Although his being the sole documented proof of a painter originally from the Orient, in Minas, at the time, it seems plausible that other painters from Asia were active in similar conditions elsewhere in the Colony. There is also the register of a Jesuit painter, Charles Belleville who "[...] in 1708, either surviving from a shipwreck or simply ill, and being so poor in health that was not deemed fit to continue his journey from China to Europe, settled in Salvador."15It is likely that after his lasting contacts with Oriental culture this Jesuit came to spread it in the Colony.

In a study of the Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó, in Sabará, 16 the author, Sylvio Vasconcellos, suggests that one of the sources for an 'Oriental' flavour incrementing the vogue of Chinese pictorial decorations was 'Chinese Export' wares -- besides the porcelains commissioned by the Companhia das Índias Orientais (Company of the Oriental Indies) -- frequently used in Brazil, particularly in the region of Minas Gerais. The porcelain from Companhia das Índias which during the eighteenth century came to Brazil, mostly remains nowadays in private hands, being rarely available for study by researchers. It is thus difficult to consolidate such suggestions. A fundamental source of information in this area is the pioneering study by Mafalda Zemella, 17 which certifies the effective trade between China and Brazil of such wares and porcelain. According to the author "Bahia acted as an importing entrepôt of goods shipped from Lisbon, either from Metropolitain manufactures or from other sources. It was through Bahia ([a port] nearer from Lisbon than Rio de Janeiro or Santos, being thus privileged with the advantage of lower freightage) that were imported to [Minas] Gerais, mirrors ornated with rich frames, wares from India, textiles from Damascus, and tapestries from the most famed European and Oriental factories [...]."18

Although the contemporary Portuguese Legislation strickly forbade this kind of trade, having in mind the contemporary inspection difficulties, it is supposed that it occured with frequency. Charles Ralph Boxer states that: "[...] the ships of the Carreira da Índia (India Route) which regularly anchored at Bahia on their way to Goa and Macao, were amongst the worst transgressors,'"19 Due to Macao's strategic location, from this City sailed ships to Portugal loaded with Oriental goods and products, later to be redistributed from Lisbon throughout Europe.

§2. "CULTURAL CIRCULARITY": A THEORETICAL SUPPOSITION

The expression "cultural circularity" attempts to synthesise an overview understanding of the historical cultural relations between the Orient and the Occident. In the specific context of this article it differs from Carlo Guinsburg's assertion, particularly when he contextualises it as "[...] a circularity which existed inbetween the dominant [social] classes and the subjacent [social] classes in pre-industrial Europe; a circular relationship elaborated on reciprocal relationships which concomitantly ascended and descended."20 Guinsburg's idea or "circularity" is here retaken not in direct reference to a "movement" between levels within one cultural compound but rather as a movement inbetween to distinct cultural groups. In the context of this article, "circularity" is to be understood as a "horizontal movement" independent from the stratification of a cultural hierarchy.

The commercial circuit of the Carreira da Índia's luxury goods and products fostering the "intercourse of cultural values"21 and the settlement of Asian born artists and artisans in the region of Minas Gerais, undoubtedly interacted in the production and diffusion of an 'Oriental' taste in Brazil. These factors were further affected by the surcharge tendency that the local painters of the Colonial period for copying imported European models. 22 The previous references made in this article to the organ of the Sé, in Mariana and to the 'porta de Macau' of the Chapel of the Santíssimo Sacramento in the Mother Church, in Sabará -- which motifs, as already stated have similarities with those of the panels of the backrests of the stalls of the Chancel of the Sé, in Mariana -- already refuted the possibility of these examples being the inspirational models for further 'Oriental' contemporary art production due to the discrepancy not only in their manufacture but also in the handling and technique of their compositions.

Frontal view.

Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó (Our Lady of 0), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

One (bottom on the Epistle side) of seven chinoiserie panels.

Eighteenth century.

Landscape composition in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer dark ultramarine monochrome background.

Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó (Our Lady of Ó), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The High Altar seen from the nave.

The seven chinoiserie panels incorporated in the carved and gilt woodwork lining the backwall can be seen surrounding the altar.

High Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó (Our Lady of Ó), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença

One (centre on the Epistle side) of seven chinoiserie panels.

Eighteenth century.

Landscape composition in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer dark ultramarine monochrome background.

Chapel of Nossa Senhora do Ó (Our Lady of Ó), Sabará.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Nonetheless the European influence is not to be discarded. All the findings of 'orientalismos' ('Orientalism') in Minas Geris clearly indicate that they are an historical consequence of previous European fashions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, originating in the mercantile and cultural maritime contacts with the East. This is not the right place to discuss the signifier and roots of the term 'orientalismos', which long became a standart in Art History terminology. But, in the particular context of this artile, the term 'orientalismos' came to acquire a more precise dimmension, meaning not only an "[...] aesthetic solution related to an aesthetic problem, but also [...] the outcome of a particular interest for the lands of the Orient; an interest specifically derived from the narrative tradition of Oriental Travel Literature."23

The facade.

Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Yaci-Ara Froner Gonçalves

The inner chinoiserie panels of the two doors (open) of the organ's box - detail.

Eighteenth century.

Architectural and paisagistic compositions in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer dark ultramarine monochrome background.

Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The organ with its musical box panels open.

Eighteenth century.

Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

The outer chinoiserie panels of the two doors (closed) of the organ's box-- detail.

Eighteenth century.

Architectural and paysagistic compositions in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer sanguine monochrome background.

Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Raquel Ferraz Proença.

Starting with the first exploratory travels of Marco Polo to China and continuing with the literary and iconographic testimonies left by all future Europeans travellers of the Orient, a defined 'image' of the East became gradually structured in the 'imagination' of the Europeans. This 'image' came to be generally accepted in the West as the cultural reality of those remote Civilisations. It was only in the eighteenth century that philosophers such as Montesquieu and Voltaire rationally questioned, in literary essays based on direct research on Oriental social and cultural sources, the acquired European 'image' of Oriental culture.

Voltaire's Zadig (1747), is a philosophical tale where secular Oriental wisdom is transmitted by the traits' description of the major protagonist of the story, Zadig, a Babylonian sage tangled in the meshes of his own destiny. The narrative cunningly explores a series of accidents experienced by Zadig in the course of his destiny, by giving sapient delivery recipes which the hero uses to free himself from the hazardous succession of events. Montesquieu Lettres Persanes (1721) uses the visionary travels of two characters who meander through France during the last years of the reign of Louis XIV [°1638, r.1643, †1715] as a moral and political critique of French society during the period of this absolutist King.

According to Paul Hazard "[...] if the eighteenth century was to be defined by a word or action then, probably, the term 'discovery' and the concept of 'travel' would be the most adequate."24 Antoine Galant's translation in French of the One-Thousand-and-One Nights (1704-1711) brought to the knowledge of the European public more precise notions of Oriental customs, usages and manners. Contemporary painters made an attempt to faithfully reproduce the lacquer and varnish techniques of China and Japan. Antoine Watteau (°1684-†1721) painted an interior decoration in the Chatêau de la Muette with chinoiseries and François Boucher (°1703-†1770) compiled in his Sequence de figures Chinoises pattern models which were to be widely copied throughout Europe. Boucher came to be the favourite painter of Mme de Pompadour, 25 the most prestigious painter of his times in France and one of the most praised French painters of the eighteenth century.

Derived from the contacts with the Orient, the European literary and iconographic 'exotic' material came to spark the imagination and curiosity of the Western public in general towards those Eastern lands, so adventurously remote and full of mystery. This artistic output came to inflate in the European market the aura and demand for rare and precious Oriental goods, such as the "ardentes especiarias" ("burning spices") -- as were so aptly described by Camões. 26 Equally, Chinese silk and porcelain were much sought after in Europe, not only for the exclusive clientéle they addressed and excessive prices they fetched, but because they were material presences of those cultures and tangible realities of their excellence. In Europe, until the eighteenth century the geographically charted Orient by the mercantile fleets and overland traders was generically known as 'Indies', although this appelation included the lands of Arabia, India, China and Japan.

A broad compilation of early European decorations with chinoiseries illustrates two major factors: first, that these decorations were mainly executed in secular aristocratic interiors; second, that in those palatial residences this type of decoration was particular to intimate study-rooms of small dimensions. The earliest example of this decorative genre is to be found in the Castle of Rosenberg, in Copenhagen, and was executed in 1617. The room is lined with wall panels depicting pseudo-Chinese compositions where human figures, painted in gold are scattered on a continuous green-and-black imitation of lacquer, background. Other outstanding eighteenth century chinoiserie decorations are to be found in the Royal Palaces of Aranjuez, near Madrid; Schönbrunn, in Vienna; Queluz, near Lisbon; and Stadt, in Low Saxony, Germany. One of the monumental interiors of the Old Library of the University of Coimbra, in Portugal, equally depicts figurative chinoiserie compositions on panels of alternated blue, red and green monochrome backgrounds. 27

The Chancel and the High Altar seen from the mouth' of the nave.

The twenty chinoiserie panels incorporated in the backrests of the stalls -- symmetrically opposite -- lining the lateral walls of the Chancel, are partially visible.

Chancel and High Chapel in the Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Yaci-Ara Froner Gonçalves.

Two Chinoiserie panels in the backrests of the stalls in the Epistle side of the Chancel-- detail (two out of ten panels).

Paysagistic and figurative compositions in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer sanguine monochrome background. Eighteenth century.

Chancel of the Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Yaci-Ara Froner Gonçalves.

Six Chinoiserie panels in the backrests of the stalls in the Epistle side of the Chancel-- detail (six out of ten panels).

Paysagistic and figurative compositions in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer sanguine monochrome background. Eighteenth century.

Chancel of the Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Yaci-Ara Froner Gonçalves.

Two Chinoiserie panels in the backrests of the stalls in the Evangile side of the Chancel-- detail (two out of ten panels).

Paysagistic and figurative compositions in gold paint over a patinated imitation lacquer sanguine monochrome background. Eighteenth century.

Chancel of the Sé (Cathedral), Mariana.

Photograph by Yaci-Ara Froner Gonçalves.

Europe was undoubtedely the access channel to an inspirational source which mixed plastic expressions resulting from the cultural intersection of disparate Asian Civilisations. Thus, paradigmatically originated, the European chinoiseries were later transported to the overseas Colonies of its major Western Powers, and specifically in Brazil, gave rise to the 'orientalismos' genre. The following phrase by Jose Maravall is an adequate conclusion to this essay: "[...] una cultura dispone siempre de préstamos y legados, los cuales le llegan de otras precedentes y lejanas, és algo facil de comprobar." ("[...] it is not difficult to ascertain that any culture is always a compound of borrowings and bequests, originating from others [cultures], preceding and 'distant'.”). 28

Translated from the Portuguese by: Maria Kerr

NOTES

1BUSCHIAZZO, Mario Jose, Influencias exoticas en la arte colonial, in "La Prensa", Buenos Aires, 29 Ab. [April] 1945 -- These and other examples were mentioned by this author in the mentioned article, which equally contain a number of references to Brazil.

2 FREIRE, Gilberto, O Oriente e o Ocidente, in "Sobrados e Mocambos", 2 vols. Rio de Janeiro, José Olympio, 1985, vol.2, p.424 [7th edition].

3 BURTON, Richard, Viagem do Rio de Janeiro a Morro Velho, São Paulo - Belo Horizonte, EDUSP-Itatiaia, 1976.

4 BRAJNIKOV, Eugénie M., Traces de l'influence de l'Art Oriental sur l'Art Brésilien du début du XVIIIe siècle, in "Revista da Universidade de Minas Gerais", Belo Horizonte, (9) Maio [May] 1951, pp.40-60.

5 BOSCHI, Caio César, Os leigos e o poder, São Paulo, Àtica, 1986 -- This is the most complete and up-to-date study on social organization in Minas Gerais.

6 The genre of Chinoiserie may be divided into four major Periods.

· 1650-1715: First Period -- There is a general tendency to directly adapt either original elements or close imitations to built 'structures'. Strong emphasis of lacquerwork and porcelain.

· 1715-1730: Second Period -- It develops mainly in Germany and more tamely, in France. The idea of a faithful replica is abandoned in favour of a creatively transformed exotic outlook.

· 1730-1770: Third Period -- The original elements are modified acquiring the particular characteristics of this genre, which are exceptionally expressed both in the Decorative Arts and in the paintings of Watteau and Fragonard.

· 1750-ca1800 Fourth Period -- It deals mainly with outdoor environments, specially garden layouts which avoid geometry in favour of a 'naturalistic' landscaping. See: YAMADA Chissaburo, Dei chinamode des spätbarock, Berlin, Würfel, 1936; ABRANTES, Dalva, Chinoiserie no Barroco mineiro, São Paulo, 1982, pp. 107-108 (mimeographed) -- MA Dissertation, Escola Central de Arte (Central Art School/(Universidade de São Paulo) University of São Paulo.

7 SCHÖNBERGER, Arno-SOEHNER, Alldor, Chinoiserie and the Exotic East, in "The Rococo Age: Art and Civilization of the 18th century", London - New York, Mcgraw-Hill 1960, p.87.

8 HOUGHTON, A. G., La pintura china, Buenos Aires,Mexico, Breviario del Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1954, p.39 -- According to the author 'flowers and birds' is a genre of Chinese painting which originated in the Tang Dynasty (618-906BC).

9 MACHADO, Lourival Gomes, O Barroco em Minas Gerais, I SEMINÁRIO DE ESTUDOS MINEIROS (FIRST SEMINARY ON STUDIES ABOUT MINAS GERAIS), Belo Horizonte, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, [n. d.], p.51.

10 ÁVILA, Afonso, Igrejas e capelas de Sabará, in "Revista Barroco", Belo Horizonte, (8) 1976, p.30.

11 CHAUNU, Pierre, A civilização da Europa clássica, Lisboa, Estampa, 2 vols., 1987, vol.1, p.55.

12 BRAJNIKOV, M. Eugénie, op. cit., p.52.

13 CAVALLI, Francesca, A missão jesuítica no Japão e a arte religiosa, in "Revista Barroco", Belo Horizonte, (12) 1981, p.324.

14 AEAM: Livro de termos de admoestações, fol. 75.

15 BARDI, Pietro Maria, Influxos vindos do Oriente, in ZANINI, Walter, "História da Arte Brasileira", São Paulo, Melhoramentos, 1975, p.91 [4th edition].

16 VASCONCELOS, Silvio, Capela de Nossa Senhora do Ó, Belo Horizonte, Escola de Arquitectura da Universidade de Minas Gerais, 1964, p.27.

17 ZEMELLA, Mafalda P., O abastecimento da Capitania das Minas Gerais no século XVIII, FFLCH, Universidade de São Paulo (University of São Paulo), São Paulo, 1950 -- Unpublished Ph. D Dissertation.

18 Idem., p.72.

19 BOXER, Charles Ralph, A idade de ouro do Brasil, São Paulo, Companhia Editora Nacional, 1969 p. 177.

20 GUINSBURG, Carlo, O queijo e os vermes: o quotidiano e as ideias de um moleiro perseguido pela Inquisição, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1989, pp.11-13.

21 LAPA, José Roberto A., A Bahia e a Carreira da Índia, São Paulo, Companhia Editora Nacional - Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1968, p.21.

22 LEVY, Hannah, Modelos europeus na pintura colonial, in "Revista do SPHAN", Rio de Janeiro, (8) 1944, pp.7-89.

23 BOURDIEU, Pierre, O poder simbólico, Rio de Janeiro, Bertrand, 1989, p.269.

24 HAZARD, Paul, A crise da consciência europeia, Lisboa, Cosmos, [n. d.], p. 17.

25 FRIEIRO, Eduardo, Orientalismos nas igrejas mineiras, in "O diabo na livraria do cônego", Belo Horizonte, Itatiaia, 1981, p.164 -- The author says that Mme de Pompadour, favourite of Louis XV, King of France, had a decisive influence in the promotion of chinoiserie amongst the French aristocracy.

26 CAMÕES, Luís de, Os Lusíadas, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1889, p.54, (Canto II, strophe 4).

27 ABRANTES, Dalva, op. cit., p.109.

28 MARAVALL, Jose Antonio, La cultura del Barroco, Madrid, Ariel, 1986, p.25.

* MA in History from The Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto (Federal University of Ouro Preto), Ouro Preto. Higher specialization in Archivology. Organizer in charge of the Arquivo Histórico do Centro da Memória Cultural (Historical Archive of the Centre for Cultural Memory), of the Municipality of Santos. Responsible for the inventory of forthcoming publication: Milícias do litóral Paulista (Militias of the Paulista littoral).

start p. 121

end p.