Tea plantation under Chinese supervision, in the Botanical Gardens of Rio de Janeiro.

In: RUGENDAS, Johann Moritz, MILLIET, Sérgio, trans., Viagem pitoresca através do Brasil, Sao Paulo, Livraria Martins, 1949 [2nd edition].

Tea plantation under Chinese supervision, in the Botanical Gardens of Rio de Janeiro.

In: RUGENDAS, Johann Moritz, MILLIET, Sérgio, trans., Viagem pitoresca através do Brasil, Sao Paulo, Livraria Martins, 1949 [2nd edition].

Author of numerous articles and publications on related topics, amongst others: O descobrimento do Japão pelos Portugueses: 1543 (The Discovery of Japan by the Portuguese: 1543), Rio de Janeiro, 1943; Nagasaki: cidade portuguesa no Japão (Nagasaki: A Portuguese City in Japan), Lisbon, 1969; Notícias da visita feita a algumas terras do Alentejo pela primeira embaixada japonesa á Europa:1584-1585 (News of the Visit to some Places in Alentejo by the First Japanese Embassy to Europe:1584-1585), Evora, 1969; O galego Pero Diez, um dos primeiros europeus que descreveram o Japão (The Galician Pero Diez, one of the First Europeans who Described Japan), Vigo, 1971; Os roteiros do Japão do Códice Cadaval (The Japanese Itineraries of the Codex Cadaval), Lisbon, 1972; Macau e o comércio português com a China e o Japão nos séculos XVI e XVII (Macao and Portuguese Trade with China and Japan during the Sixteenth and the Seventeenth Centuries), Macao, 1973; O Namban-ji, Templo dos Bárbaros do Sul, de Kyoto (The Namban-ji, the Temple of the Barbarians of the South, in Kyoto), Macao, 1976.

INTRODUCTION

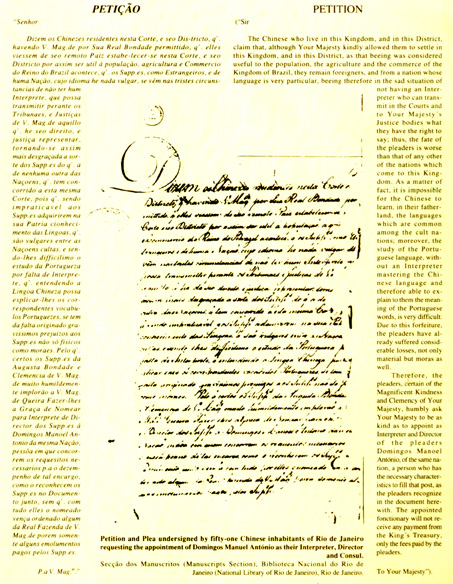

The history of the relations between Macao and Brazil remains unwritten. A great deal of researching among Brazilian, Macanese, and Portuguese documentation, as well as among documents from other sources, is yet to be done.

Far more numerous than is generally thought, are the references to Chinese articles in Brazil, mainly in the documents and chronicles of the eighteenth century and of the beginning of the nineteenth: tea, medicines ('Chinese root', rhubarb, etc.), several different qualities of cloth ('Nanjing silk', scarves, blankets, jackets, satin quilts, 'Nanjing cotton', etc.), paper and silk paintings, fans, jewellery, lacquer boxes, pottery, flowerpots, earthenware, ceramics, 'Macao crockery', furniture, art objects, fire-crackers, etc.

More than half a century after the independence of Brazil, one of the elements in the Diplomatic Mission that went to China to discuss the first Treaty between the two Empires was amazed to find furniture which was familiar to him in Guangzhou:"[...] huge beds which are still found in Portugal and Brazil, brought from Macao by our grandparents."1

How did the beautiful and strange sculpture of a Chinese lion showing its teeth, which guards the entrance of the church of the Franciscan Convent of Sto. António (St. Anthony), find its way to Paraiba? 2

§1. NEWS OF THE CHRONICLER GONÇALVES DOS SANTOS IN HIS MEMORIAS (MEMOIRS)

The relations between Macao and Brazil became increasingly more intense in the period in which the Portuguese Royal Court stayed in Brazil (1808-1821). The chronicler Fr. Luís Gonçalves dos Santos (°1767-†1844), also known by the nickname of 'Father Perereca', gives, in his important work Memórias para servir á história do reino do Brasil, much news on this subject, which we will summarise. 3

(Ansicht vom Schloβe Sa. Cruz vom Osten und dem chinesischen Garten). View of the Santa Cruz farm[fazenda]. THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.227.

(Ansicht vom Schloβe Sa. Cruz vom Osten und dem chinesischen Garten). View of the Santa Cruz farm[fazenda]. THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.227.

In 1809 a ship arrived in Rio de Janeiro carrying a great number of Portuguese who, having been prisoners of the French on the 'Island of France'** in the Indian Ocean, managed not only to negotiate their departure to Brazil but also to secretly buy a large amount of seeds of Oriental plants which were cultivated in the local Botanical Garden. Among them was Rafael Botado de Almeida, Senator of Macao, who played an important role in the repatriation process and in the risky acquisition of the new vegetal specimen.

The chronicler mentions the Alvará (Ruling) signed by the Prince Regent Dom João, in the 13th of May 1810,"[...] through which he kindly exempted Chinese merchandise, directly exported from Macao to the State of Brazil aboard Portuguese ships, from paying the entry fees in the Brazilian Customs. Likewise, through the licence of the 7th of July, he granted exemption from tithe contribution and entry Rights."4

Concerning this Ruling he adds the following considerations:

"Through these Régios Diplomas (Royal Statutes) we can clearly see the measures that the Regent Prince Our Lord constantly adopts so as to enrich and make prosperous His vast Empire of Brazil, enlivening commerce, favouring agriculture, and stimulating industry. In effect, if Rio de Janeiro and Bahia are to become the trading posts of the merchandise of China, what profits can not we expect for the future of this commerce with Asia? Once foreign traders find, in any of these great markets, the goods in which such a long journey, great expenses and risks are involved, they most certainly will choose to come to Brazil instead of travelling as far as Macao and Guangzhou. The Portuguese of both hemispheres will be able to carry these very same Chinese goods aboard their own ships, and take them to the ports of Europe earning great profit, since those [goods] are exempt from entry Rights in the ports of Brazil."5

(Fischender Chinese am Flope Alcobaça, Januar [?] 1816). Chinese man fishing at the River Alcobaça, January 1816.

Prince MAXIMILIAN OF WIED.

Early nineteenth Century. Ink on paper.

RÖDER, Josef-BALDUS, Herbert, Maximiliano, Príncipe de Wied: Viagem ao Brasil, 1815-1817: excertos e ilustrações, São Paulo, Melhoramentos, 1969, p.35.

(Fischender Chinese am Flope Alcobaça, Januar [?] 1816). Chinese man fishing at the River Alcobaça, January 1816.

Prince MAXIMILIAN OF WIED.

Early nineteenth Century. Ink on paper.

RÖDER, Josef-BALDUS, Herbert, Maximiliano, Príncipe de Wied: Viagem ao Brasil, 1815-1817: excertos e ilustrações, São Paulo, Melhoramentos, 1969, p.35.

Fr. Gonçalves dos Santos also mentions the Ruling, dated from the 4th of February 1811 which, in order to stimulate commerce and navigation, revoked the Ruling of 8th of January 1783, the Decreto (Decree) of 29th of January 1800 and the Rulings of 17th of August 1795 and 25th of November l800:

"Being inapplicable in the current circumstances and unsuitable for the high purposes which the same Royal Lord established in the organisation of a whole plan and general system of commerce, which encompasses all the Countries and Domains in the four parts of the World and intends to eliminate the obstacles which closed a part of the ports in his Domains to the commerce with other ports in his very same Domains, His Royal Highness, considering that the geographical position of Brazil is in itself the most favourable and appropriate for the constitution of a commercial Empire between Europe and Asia, decided, by the same Ruling, to liberalise through ample concessions to His faithful subjects, the direct commerce and navigation on the seas of India, China, bays, rivers and islands, both national and foreign, beyond the Cape of Good Hope, as well as in the ports of Portugal, Brazil, Azores Islands, Madeira, Cape Verde Islands, West African ports, and neighbouring islands belonging to His Royal Crown; abolishing all the restrictions which, for so many years obstructed the ways of prosperity, opulence and power which in former times raised the Portuguese Nation to the highest peak of its glory."6

In a note of 1815, concerning the opening of the Brazilian ports, the chronicler mentions the "[...] Chinese who came from Macao in great numbers and established themselves in the Court." -- then in Rio de Janeiro. In another note, he mentions their presence in the celebrations of the acclamation of Dom João VI: "[...] there, we could see, mixed with Portuguese, foreigners from many a nation, English, French, Germans, Italians, Spanish and even Chinese, in avid expectancy of being witness to the glorious acclamation of our August King."7

Finally, we would liked to mention the transcription, by the chronicler, of two documents of the same date which correspond to the geminating of the City of Rio de Janeiro with Macao. On the 6th of February 1818, day of the acclamation, in Rio de Janeiro, of the King Dom João VI, He signed two Rulings; one, granting the treatment of Senhoria to the Câmara Municipal (Municipal Council) of Lisbon, and another one granting the same treatment to the Leal Senado (Loyal Senate) of Macao:

Ruling 1 -- "The King, bring to the knowledge of all who see this Ruling that, being my will to distinguish with high appreciation the Municipal Council of this City of Rio de Janeiro which, besides being the capital of the Kingdom of Brazil also had the honour of witnessing My Glorious Coronation, and swearing by the inhabitants of this City, who gave me the most faithful and decisive proofs of their loyalty and love to My Royal Person: determine to grant it the status of Senhoria. This shall be fulfilled as herewith."8

The Ruling concerning Macao reveals that the City sent a Deputy to Rio de Janeiro, to represent it in the ceremonies of the King's acclamation:

Ruling 2 -- "The King, bring to the knowledge of all those who see this Ruling that, being my will to give to the Loyal Senate of Macao a testimony of the consideration which it deserves to Me for the services which it has rendered in the fulfilment of the duties which have been commissioned to it, and especially by the faithful feelings of love and loyalty shown towards My Royal Person by sending from so far a Deputy to congratulate Me for My Ascent to the Throne and to through him pay homage in this most happy day of My Coronation: determine to grant it the status of Senhoria. This shall be fulfilled as herewith."9

§2. MACAO AND THE BOTANICAL GARDEN OF RIO DE JANEIRO

According to the Baron of Rio Branco, the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro was created by a Ruling dated the 1st of March 1811. 10

Meanwhile, before that date, "the first species from abroad" arrived in Rio de Janeiro: seeds brought from the 'Island of France' with the help of Senator Rafael Botado de Almeida, as mentioned by the chronicler Gonçalves dos Santos. The ship which carried them arrived in Guanabara in July 1809.

The Chefe de Divisão (Division Chief) for the Royal Navy, Luís Abreu de Vieira e Paiva, who led the repatriation, was praised by King Dom João VI for having brought the seeds:

"His Royal Highness praised the Chief, not only for the mentioned service, but also for the important acquisition to the Country, of twenty boxes of exotic plants and spice trees which were offered to His Highness, in order to enrich His States of Brazil with the Asiatic preciosities which in former days M. M. Poivre and Menonville, in 1770, had acclimatised on the Island of France."11

Among the seeds were muscade, camphor, avocado, leeche, mango, cloves of India and grapefruit. The seeds were immediately sent to the Quinta Real (Royal Farm) and to the "Garden of the Freitas lagoon" by order of King Dom João IV. That Garden was a place, close to the Gunpowder Factory of the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon, which the Prince Regent had reserved to the acclimatisation of plants and where, soon afterwards, the Botanical Garden was installed.

Soon after the arrival of the Oriental seeds and, surely, due to the enthusiasm caused by this arrival, the Junta de Comércio (Board of Commerce)issued an Edital (Edict), dated from 27th of July 1809, publicly expressing that the Prince Regent had authorised "[...] the mentioned Board to establish prizes to award those who successfully acclimatise anywhere in My States and Domains, the fine spices of India, and those who introduce the culture of plants, aboriginal or foreign which are required in pharmacy, dying and other arts."12

Thus, in July 1809 the seeds arrived. On the 27th July of the same year the Ruling established prizes to award those who acclimatised the plants. On the 1st of May 1811 the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro was created.

In a Report dated from the 4th of March 1813, published in the newspaper "O Patriota" in that same year, the Division Chief Videira e Paiva emphasised the help of Senator Botado de Almeida and others in the acquisition of the seeds:

"It is a duty of justice to mention how important is the success of such an interesting acquisition to this State, the efforts, secrecy and money of the mentioned Senator Botado de Almeida, Francisco João da Graça and António José de Figueiredo, ship's doctor; the names of these three good Portuguese are worthy of being remembered for posterity, due to the many patriotic acts practised by them in that Colony during our imprisonement."13

But the contribution of the Senator of Macao to the Botanical Garden was not limited to that action. Upon his return to Macao in 1812 he sent at the request of Luís de Abreu, seeds of tea, as is mentioned in the Report:

"I think it is also my duty to inform you that having requested my dear friend Rafael Botado de Almeida, Senator of Macao, to be sent the seeds of the tea plant, I received last year a great number of them which I have distributed, giving them to His Excellency the Lieutenant General, the Deputy of the Royal Board of Commerce, José Caetano Gomes, and to several other persons."14

The Lieutenant General mentioned by Luís de Abreu was Carlos António Napiôn, Director of the Gunpowder Factory of the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon and of the attached Botanical Garden.

But the contribution of Macao does not end here. Through the City of the Holy Name of God also came the first Chinese immigrants, to cultivate tea in the Botanical Garden.

§3. THE CHINESE AND THE CULTIVATION OF TEA IN THE BOTANICAL GARDEN OF RIO DE JANEIRO

According to several historians, the project to introduce Chinese settlers in Brazil is due to the Earl of Linhares, Dom Rodrigo de Sousa Coutinho, who was the Minister of Foreign Affairs and War, in Rio de Janeiro, from 11th of March 1808 until his death on 26th of January 1812. Some foreign travellers who arrived in Brazil years after the death of the minister also attribute the initiative to him.

Meanwhile, we still have to find the documentation concerning the arrival of the first Chinese, in order to clarify several doubts, such as the exact date of arrival, their number, where in China they came from, contract conditions, etc. 15

Johann von Spix and Karl Friedrich Philipp von Martius, who arrived in Rio de Janeiro in 1817, visited and described the Botanical Garden and they mention the Chinese who worked there:

"Several beautiful alleys of bread-fruit trees from the Pacific Ocean (Artocarpus incise), ironwood trees of dense foliage (Guarea trichilioides) and mango trees cut the plantation, which is divided in regular squares, the most important goal being the cultivation of the Chinese tea plant. Until now six-thousand small plants, three feet apart from each other, have been planted, in rows. The climate seems to be favourable to their growth; they are in flower in the months of July and September, and the seeds ripen quite perfectly. Also this example, besides other attempts to cultivate Asiatic plants in America, confirms that, above all, the equality in latitude is important for the prosperity of the transplants. Tea is cultivated, harvested and toasted in the same manner as in China. The Portuguese Government has dedicated special attention to the cultivation of this plant, whose Chinese product is annually exported to England, to the value of twenty-million Escudos. The ex-Minister, the Earl of Linhares, sent for a few hundred Chinese settlers, in order to bring to light the culture and manufacture of tea. It is said that those Chinese were not coastal inhabitants, who seek exile in Java and the neighbouring islands, and like the Galicians from Portugal and Spain, who look for work there; they were people from the interior, especially chosen for their skills in the cultivation of tea."16

When these two German scientists visited the Botanical Garden, only a few Chinese were actually living there, taking care of the plantation, harvesting and preparation of the tea leaves, working under the supervision of the Director of the Gunpowder Factory, Colonel João Gomes Abreu. The majority of them were already living at the fazenda (farm) of Santa Cruz.

(Chinesen von der koenigl Thee Pflanzung zu Sa. Cruz). Chinese workers from the tea plantations of Santa Cruz

THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.233.

(Chinesen von der koenigl Thee Pflanzung zu Sa. Cruz). Chinese workers from the tea plantations of Santa Cruz

THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.233.

The leaves were harvested twice a year, submitted to a process of drying in clay ovens and then rolled. The Director offered tea of different kinds, according to the time of the harvest, for them to taste:

"The flavour was strong. However, it was far from the exquisitely aromatic taste of the finest Chinese qualities of tea; it was somehow sour and earthy. This, however, should not be a matter of regret in any branch of this culture, for it is a natural consequence of an acclimatisation which is not yet complete."17

Another German traveller, the draughtsman Johann Moritz Rugendas, who visited the Botanical Garden almost a decade after, begins is description by stating:

"The attempts which up until now were made to cultivate tea are mainly due to the former Minister, the Earl of Linhares. Some years ago he sent for a quantity of seedlings and a few Chinese to take care of them and he made a farm behind the Corcovado, on the shore of the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon, near the Jardim das Plantas [Botanical Gardens]. The number of bushes was, in 1825, six-thousand."18

In many places Rugendas almost repeats the same information of Spix and Martius, like the distances between the bushes, the harvesting, drying in clay ovens, etc. And even the flavour:"[...] it does not have the fine aromatic flavour of the prime quality Chinese varieties; on the contrary, it has a bitter, earthy taste." He also thought that that was due to the fact that the plant was not yet acclimatised, and presented two possible answers -- deficiencies in the treatment of the leaves, mainly during the drying process, and the careless choice of the Chinese (perhaps not all of them were acquainted with working with tea before). He praised the experiment attempted by the Government and said that, although until then the results nor been entirely satisfactory, nevertheless they should start to improve very soon.

(Chinesische Kleidung neben der Art Tabak zu rauchen). Chinese Outfit and how to smoke Tobacco.

THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.117.9 (3-4) Outono-Inverno [Autumn-Winter] 1975, p.75.

(Chinesische Kleidung neben der Art Tabak zu rauchen). Chinese Outfit and how to smoke Tobacco.

THOMAS ENDER Early nineteenth century. Ink on paper.

In: FERREZ, Gilberto, O Brasil de Thomas Ender: 1817, Rio de Janeiro, Fundação João Moreira Salles, 1976, p.117.9 (3-4) Outono-Inverno [Autumn-Winter] 1975, p.75.

Furthermore, he commented on the great expenses of England in the acquisition of Chinese tea(three-million pounds -- weight paid in Piastras), and considered the entry of Brazil into that market as a benefit:

"The number of Chinese settled near the Rodrigo de Freitas lagoon and the farm of Santa Cruz is of more or less three-hundred and among that number only a few are involved in the culture of tea: many are servants, others cooks. The Chinese adapt very well to the climate of Brazil and some of them even marry."19

Another German traveller, Carl Sneider, also mentioned, about the same time (1825), the culture of tea:

"The tea, which the Portuguese King Dom João VI transplanted to Brazil around 1816, is the only product of exception, for it is collected according to the rules. With great pain and difficulties they sent for Chinese from their faraway Country, to cultivate tea in Brazil with the methods used in China. It was a fortunate and successful idea. The tea which is produced here is only slightly inferior to the Chinese variety."20

The information collected by Seidler, stating that the Chinese came around 1816 is corrected by documents which show the presence of Chinese in August 1814, in Bahia and Rio de Janeiro, and in September of the same year, in the Real Fazenda of Santa Cruz, as we shall see next.

Seidler criticises the lack of supervision in the plantation, and says that if it was made with some care and intelligence, Brazil would soon be producing all the tea needed for its consumption, making a great economy each year. Meanwhile, the Government, in spite of being in a "[...] state of financial wreck, thinks that it is of no use to improve that species, which could one day bring the greatest profits. [And he adds:] Of course, the English do all in their power to create obstacles to those plantations; but is it possible that such a great independent Empire like Brazil is unable to energetically fight this vile spirit of speculation of its uninvited guests?"21

The English Maria Graham, who was at the Botanical Garden in 21st of December 1821, writes in her journal:

"This garden was destined by the King for the culture of spices and Oriental fruits and, above all, to the culture of tea which he had sent from China along with a few families used to its culture. There is nothing more prosperous than the group of the plants [...] I particularly noticed the jambo (Jambo mallaca) of India and the longona (Euphoria longona), a kind of litchi from China."22

§4. CHINESE AT THE REAL FAZENDA OF SANTA CRUZ

The Arquivo Nacional do Rio de Janeiro ([ANRJ] National Archive of Rio de Janeiro) keeps documents about the Chinese who were sent to the Real Fazenda of Santa Cruz, a former propriety of the Jesuits, incorporated to the assets of the Crown in the second half of the eighteenth century and adapted as a summer palace, when the Court moved from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro as a result of the invasion of Portugal by Napoleon's armies. 23

In September 1814, the Chinese were taken to Santa Cruz to choose the lands where they should settle:

"After taking the Chinese to visit and choose the lands for their plantations in the Real Fazenda, the Officer António Gomes da Costa told me that at first they were pleased with the site in Morro do Ar and the one of Chaperó and, when I spoke to them myself, I was told the same. Morro do Ar is very close to Hespanhóis and to the farms of the slaves and the Chaperó is already settled. However, since the Chinese only want a small portion of land, for their plantations are different from those in this Country, they can be placed wherever Your Excellency desires."24

On the 24th of December 1814, the Minister of the Navy and Overseas, António de Araújo e Azevedo (who later became the Earl of Barca), wrote to the Treasurer of the farm of Santa Cruz, João Fernandes da Silva: "In view of the need to send a few Chinese there, I request that you warn me when the house which is being prepared for them is ready."25

On the 7th of January 1815, the Treasurer answered from Santa Cruz, saying that the "[...] house for the settling of the Chinese will be ready by Monday the 9th of this month; the delay was due to continuos rains that have occurred lately."26

The accountancy of the Real Fazenda of Santa Cruz registers several expenses with the Chinese. A bill of the 31st of January 1816 refers the expenses with "[...] paint for the doors of the Chinese (China vermilion), white lead, linseed oil, etc.). [...] With the Chinese themselves were also spent 432.00 réis for forty-eight sacks of rice, 120.00 réis for forty-five kilos of bacon, 13.20 réis for twelve kilos of salt and a monthly salary of 32.00 réis paid to forty-five Chinese, totalling 1,440.00 réis)."27

Another Bill of the 31st of May of that year mentions seventy-five sacks of rice, more or less seventy-five kilos of bacon, salt and monthly salaries of 32,00 réis paid to seventy-five Chinese, totalling 2,304.00 réis."28

On the 30th of April there was a bill concerning the same kind of products: rice (105 litres), bacon and salt, and monthly salaries of 32.20 réis paid to 69 Chinese, totalling 2,208.00 réis."29

The Conta de diversos gêneros de ordem do conde da barca, Ministro e Secretário dos Negócios da Marinha e Domínios Ultramarinos (Accountancy of the Earl of Barca, Minister and Secretary of Naval Affairs and Overseas Domains), dated on the 28th of February 1819, mentions again the same products and "[...] the payment of monthly salaries of 32.00 réis to fifty-four Chinese, totalling 1,718.00 réis."30

The last accountancy document we have researched, the Receita corrente da administração da Real Fazenda de Santa Cruz, de 1. ° de Maio a 31 de Dezembro de 1821 (Revenue of the Administration of the Real Fazenda de Santa Cruz, from the 1st of May to the 31st of December 1821), mentions among the salaries to the employees of the farm, "[...] 229$840 to the Chinese."31

Dated the 6th of October 1816, there is a description of the celebrations and ceremonies made by the Chinese on the previous day and is included in the report send by the Treasurer João Fernandes da Silva to the Earl of Barca. Due to its extreme interest, it is published here for the first time:

"[...] in compliance with what Your Excellency had determined I went to the celebration to which the Chinese had invited me. Arriving at noon in the company of my family and the Officer António Gomes da Costa, leaving the patrol at the farm, so as not to cause any surprise, I found them at the cafe, with a table laid outside the house, opposite the gate of the cafe facing the direction were the moon rises. There was half a roasted pig on the table, a duck on one of the sides, and a plate with pig entrails on the other, two bottles of firewater, two candleholders with lighted candles, and a few cups. On the floor, by the table, there was a mat to which they came in groups of three, taking their shoes off and kneeling on top of the mat to kiss the soil, then they would get up to cut a piece of the pig entrails into a bowl, going around the table to sprinkle the ground by using two chopsticks with which they eat; they would then kneel on the ground once more and return to their place while another group would follow in the same way. After having finished this procedure they cleared the table and all went to eat on the ground, joyfully offering us their food; and after the meal they brought a few books in Chinese writing, giving me one of them and another to the Officer. We took the books and then returned them, while they sat on the floor, each with his book, and started to sing in dissonant voices; by then it was already night time. From there I went to visit the ones in the new house, the ones in charge of the tea. They were also very joyful and offered us tea and peanuts. The moon was already high on my return home, after which I sent the patrol to see, as discreetly as possible, if there was any disorder. However, the Chinese finished their celebrations quietly. This afternoon, according to the orders of Your Excellency, I shall call the patrol back for it is not needed anymore in this case."32

On the 10th of December 1817 the German scientists Spix and Martius arrived at the farm:

"In order to benefit the Fazenda of Santa Cruz the previous Minister, the Earl of Linhares, arranged houses for the majority of the Chinese settlers who were sent to the country."33

They saw that only a small number of Chinese were living there at that time. The majority had left for the City to make a living from the commerce of "[...] small Chinese artifacts, especially cotton fabric and firecrackers. They observed that diseases, homesickness and inability to adapt to the new environment had caused a great number of losses among the Chinese. Those who remained made small plantations of coffee and of their favourite flowers, jasmine and basil, around their small and very clean huts."34

name="RETLAB2002200040037">35</a></html>

The Bohemian doctor Johann Emanuel Pohl, who came to Brazil with several other scientists accompanying the entourage of Princess Leopoldine, was at the Real Fazenda of Santa Cruz on the 19th of February 1818 and he makes a reference to the Chinese in his book <I>Viagem ao interior do Brasil (Voyage to the interior of Brazil): </I>

"First one comes to a beautiful little house with coloured lanterns and similar objects with Chinese inscriptions. In fact, this is a colony of about thirty Chinese who the King called from their homeland with the wise political intention of introducing tea into this Country."<html><RETLAB2002200040038><a href=javascript:GoToTags("LAB2002200040038") name="RETLAB2002200040038">36</a></html>

He saw about one-hundred-and-fifty bushes almost one meter tall, which seemed to him to be a variety of <I>Thea bohea, </I> which is grown in the Province of Fujian. The plant was growing well even in the sandy soil, in rows which were twenty metres long and forty-five metres wide. The plantation was "[...] watched by a solemn faced Chinese, walking back and forth."

Pohl noticed that the soil and the climate were undoubtedly, suited to the culture of tea but he said that"[...] unfortunately there was a mistake in the selection of the planters and, besides this, it seems that due to a totally wrong point of view, they ceased to make the privileges of the Chinese depend entirely on the success of the tea plantations. The Chinese, of course, care much less about them than they do about the profitable culture of coffee or the quiet business of selling used articles, something which they do in Rio de Janeiro and other Cities."<html><RETLAB2002200040039><a href=javascript:GoToTags("LAB2002200040039") name="RETLAB2002200040039">37</a></html>

He furthermore adds that due to the small dimension of the plantation, the revenue was disproportionately inferior to the expenses, and that the King was forced to dismiss the Chinese and put the exploration in the hands of other workers.

The English Maria Graham was in the Real Fazenda in 24th of August 1823 and left a pleasant description of the "China of Santa Cruz", in her journal:

"I went to the tea plantations, which occupy many acres of a rocky hill, exactly reproducing, as I suppose, the habitat of the plant in China. The introduction of the culture of tea in Brazil was a favourite project of the King <I>Dom</I> João VI, who brought the plants and the workers from China at great expense. The tea which was introduced here and at the Botanical Garden is considered to be of superior quality. But the amount is so small that up until now there isn) 38

38