PORTUGAL - SECOND HALF OF THE 19th CENTURY

Camilo Pessanha was born in Coimbra in the same year that the Minister for Justice Barjona de Freitas, abolished the death penalty in the Assembly: The Penalty that punishes blood with blood, kills but does not correct, vindicates but does not improve things. (1)

In 1867, the very same Assembly approved the Viscount of Seabra's Civil Code, which replaced at long last the outdated Ordenações Filipinas**.

Camilo Pessanha at the age of sixteen.One of the rare photographs of the poet,in Camilo Pessanha - A Imagem e o Verbo by Daniel Pires (to be published by ICM), taken from Camilo Pessanha: Elementos para o Estudo da Sua Biografia e da Sua Obra by António Dias Miguel.

Camilo Pessanha at the age of sixteen.One of the rare photographs of the poet,in Camilo Pessanha - A Imagem e o Verbo by Daniel Pires (to be published by ICM), taken from Camilo Pessanha: Elementos para o Estudo da Sua Biografia e da Sua Obra by António Dias Miguel.

We added this legal note because Camilo Pessanha was a renowned lawyer in addition to being the greatest poet of Portuguese symbolism.

At the time, Portugal was enjoying the peace brought about by the Regenerationist Movement. This was a literary movement inspired by a new European scientific belief. From 1865/66, the Regenerationists opposed an academic generation whose beliefs they considered to be stagnant. The old, conformist ideas had survived under the renowned poet António Feliciano de Castilho, the posthumous Arcadian as he was called by the young Regenerationists.

Each day, by train from France and Germany, there came trends of new things, ideas, systems, aesthetics, shapes, feelings, humanitarian interests (2)which helped the establishment of the Realism school and influenced the Lisbon Casino Democratic Conferences, an event promoted by Antero de Quental and Eça de Queirós.

Meanwhile, Camilo Pessanha was growing up: My childhood by name alone, since as far as I can recall, I did not have one' was in various places, always moving with his father who was a magistrate: Coimbra, Tábua (his mother's town in Beira Alta), Azores and Lamego.

In 1884, at the age of seventeen, he joined the Coimbra University on the same day he was to be legitimized. Even though this late legitimation gave him social dignity in the academic environment, he was never able to eradicate the grievances suffered since he was a child due to the fact that his mother was condemned to the role of a maidservant or a housekeeper:

Quem poluíu, quem rasgou os meus lençóis de linho,

Onde esperei morrer, - meus tão castos lençóis?

Do meu jardim exíguo os altos girassóis,

Quem foi que os arrancou e lançou no caminho?

Quem quebrou (que furor cruel e simiesco!)

A mesa de eu cear, - tábua tosca de pinho?

E me espalhou a lenha? E me entornou o vinho?

- Da minha vinha o vinho acidulado e fresco...

Ó minha pobre mãe!... Não te ergas mais da cova.

Olha a noite, olha o vento. Em ruína a casa nova...

Dos meus ossos o lume a extinguir-se breve.

Não venhas mais ao lar. Não vagabundes mais.

Alma da minha mãe... Não andes mais à neve.

De noite a mendigar à porta dos casais.

By the time he started his law course, the Portuguese delegation to the Berlin Conference had left for Germany. This was held under the auspices of Bismark for the setting up of the new international law concerning colonial possession. In order to be accepted, the historic right argued by the Portuguese called for an effective occupation which required a new division of Africa among Europe's richest and most developed countries. Portugal, a poor country with a weak military force and scarce labour to carry out the colonization process, saw its secular influence in Africa in danger.

Taking advantage of this climate, the Republican Party accused the monarchy of not being able to respond to the murderous insults from abroad.

But in 1890, with the Ultimatum, the most serious insult made to the country's historical past, criticism reached new heights. Guerra Junqueiro said:

A Pátria é mortal a Liberdade é morta.

Noite negra sem astros, sem sem faróis!

Ri o estrangeiro odioso à nossa porta.

Guarda a infâmia os sepulcros dos heróis! (3)

What about Camilo Pessanha? His vibrating Portuguese emotions forced him to write the following lament:

Eu vi a luz em um país perdido.

A minha alma é lânguida e inerme.

Oh! Quem pudesse deslizar sem ruído!

No chão sumir-se, como faz um verme...

What a shame to be born in Portugal!, said António Nobre... As soon as people realized this social and cultural decadence, something that the poets had been aware of for quite some time, they developed mixed feelings of uneasiness and unrest, the fin de siècle disease, Decadentism.

In 1885, still free from Decadentism, Camilo Pessanha wrote his first poem - "Lúbrica"- warm, sensual and oneiric, which foretold his adventure in the East:

Quando a vejo, de tarde na alameda,

Arrastando com ar de antiga fada,

Pela rama da murta despontada,

A saia transparente de alva seda,

E medito no gozo que promete

A sua boca fresca, pequenina,

E o seio mergulhado em renda fina,

Sob a curva ligeira do corpete,

Pela mente me passa em nuvem densa

Um tropel infinito de desejos:

Quero, às vezes, sorvê-la, em grandes beijos.

Da luxúria febril na chama intensa...

Desejo, num transporte de gigante,

Estreitá-la de rijo entre os meus braços,

Até quase esmagar nesses abraços,

A sua carne branca e palpitante;

Assim, quisera eu, exausto, quando,

No delírio da gula todo absorto,

Me prostrasse, embriagado, semi-morto,

O vapor do Prazer em sono brando:

Entrever, sobre fundo esvaecido,

Dos fantasmas da febre o incerto mar,

Mas sempre sob o azul do seu olhar,

Aspirando o frescor do seu vestido,

Como os ébrios chineses, delirantes,

Respiram, a dormir, o fumo quieto,

Que o seu longo cachimbo predilecto

No ambiente espalhava pouco antes...

Mas não posso contar: nada há que exceda

A nuvem de desejos que me esmaga,

Quando a vejo, da tarde á sombra vaga,

Passeando sozinha na alameda...

Coimbra is a romantic and inspiring place. There the poet found an environment which induced him to write poetry. However, the city on the Mondego River was also a bohemian place, where the student ventured in the night life and absinth, a fashionable liquor in the Academy which destroyed his weak body and transformed him into a moving skeleton where only the nerves are alive, as reported by his colleague and friend Alberto Osório de Castro.

This escape from the daily life was probably due to his secret love for D. Madalena Canavarro. Disenchanted and sick, the poet sought shelter in poetry and failed to pass his fourth grade at the Law University. He finally graduated in 1891 and started working as assistant delegate to the Royal Attorney General. Later he worked as a lawyer in Óbidos, but this was not the life he wanted.

As the Government Gazette invited candidates for a teaching post at the newly established Macau High School, he applied and left for the territory.

He left, missing the present, the only real time, the one in which one actually lived, to face a future that the poets felt was potentially dangerous. It was the beginning of his eternal exile, a contradiction which the poet was never able to overcome:

CAMINHO

Tenho sonhos cruéis; n'alma doente

sinto um vago receio prematuro.

Vou a medo na aresta do futuro,

Embebido em saudades do presente...

Saudades desta dor que em vão procuro

Do peito afugentar bem rudemente,

Devendo, ao desmaiar sobre o poente,

Cobrir-me o coração dum véu escuro!...

Porque a dor, esta falta d'harmonia,

Toda a luz desgrenhada que alumia

As almas doidamente, o céu d'agora,

Sem ela o coração é quase nada:

Um sol onde expirasse a madrugada,

Porque é só madrugada quando chora.

He arrived in Macau in 1894 and started teaching philosophy at the High School, where he met Venceslau de Morais, who like him, was a voluntary exile.

Autógrafos de poemas corn variantes, correspondência, dedicatórias e fotografias de Camilo Pessanha, by Arnaldo Saraiva.

Autógrafos de poemas corn variantes, correspondência, dedicatórias e fotografias de Camilo Pessanha, by Arnaldo Saraiva.

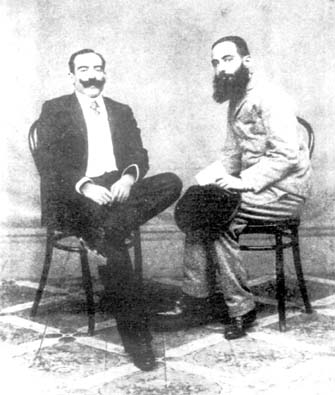

Photo of Camilo Pessanha taken in Macau (by Wen-Man Fook) with Horácio Poiares who, like him, was one of the first teachers at the High School which was founded in 1893. With the same attire and looks he is featured in one photo taken in Oporto (Guedes/Neves Guimarães). Taking into consideration Dias Miguel's statement that Camilo grew his beard only after his first trip back to Portugal, we believe that this photo was taken in 1897 whilst the Oporto one was taken towards the end of 1899. However, the latter was reproduced by the very same Dias Miguel in a book of his and it is referred to as dating from around 1897, or that it was a photo of Camilo's youth, by which time he should have been over 30. Danilo Barreiros has another photo of these two friends taken in Lisbon. The poet's sisters had more than one copy of this photo and a copy of a similar one taken on the same occasion, but he is standing. Photo and caption were taken from "Persona 10", published by the Centro de Estudos Pessoanos, Oporto, July 1984 in Autógrafos de poemas com variantas, correspondência, dedicatórias e fotografias de Camilo Pessanha, by Arnaldo Saraiva.

Photo of Camilo Pessanha taken in Macau (by Wen-Man Fook) with Horácio Poiares who, like him, was one of the first teachers at the High School which was founded in 1893. With the same attire and looks he is featured in one photo taken in Oporto (Guedes/Neves Guimarães). Taking into consideration Dias Miguel's statement that Camilo grew his beard only after his first trip back to Portugal, we believe that this photo was taken in 1897 whilst the Oporto one was taken towards the end of 1899. However, the latter was reproduced by the very same Dias Miguel in a book of his and it is referred to as dating from around 1897, or that it was a photo of Camilo's youth, by which time he should have been over 30. Danilo Barreiros has another photo of these two friends taken in Lisbon. The poet's sisters had more than one copy of this photo and a copy of a similar one taken on the same occasion, but he is standing. Photo and caption were taken from "Persona 10", published by the Centro de Estudos Pessoanos, Oporto, July 1984 in Autógrafos de poemas com variantas, correspondência, dedicatórias e fotografias de Camilo Pessanha, by Arnaldo Saraiva.

PREVAILING CONDITIONS IN MACAU AND CHINA IN PESSANHA'S TIME

According to the 1879 census, there were 60,000 inhabitants in Macau of which 4,431 were Portuguese, 78 were foreigners and the remaining were Chinese. On Taipa and Coloane there were 8,100 inhabitants, of which only 45 were Portuguese.

In 1884 there were 2,698 Chinese vessels in Macau harbours, but the city looked poor, which was a sign of its fall in trading and fishing terms. Gone were the glorious days when there were no competitors to match its ships which controlled the South China Sea trade. Anyway, Macau was not a burden to the throne. In budget terms, the city's revenue and expenditure were balanced in the last decade of the monarchy. (4)

Macau was also experiencing the consequences of the Opium War (1839-42) between dominant Great Britain and the decadent Chinese Empire, a war which reinforced the power held by the former and emphasized the downfall of the latter.

Portugal followed the new trends implemented by the European superpowers towards colonialism. A clear definition of Macau's political framework was required, as relations between Portuguese and Chinese during the previous three centuries featured many advances and setbacks. These followed the wills and circumstancial interests of the leaders of the Macau-Canton-Peking triangle.

It is in accordance with this Western way of thinking that both Ferreira do Amaral's term and the diplomatic discussions leading to the 1862 (which was never ratified by the Chinese) and 1887 Treaties (which granted Portugal the perpetual right to occupy Macau and its possessions) must be taken into consideration.

But Macau was also a gateway to the huge Middle Empire and Camilo Pessanha wasted no opportunity to observe with a lawyer's eye and describe a disintegrating world and an imperial system which was collapsing irreversibly.

With his friend Venceslau de Morais he went very often to Canton.

Nineteenth - century China experienced a series of events that changed its internal organization, such as an extraordinary increase in population during a period of economic recession; a corrupt and inefficient administration which collected the much needed money from the poor people; the Opium War with mass imports of the drug creating a hard to handle inflation, moving the trade from Canton to Shanghai and causing the ruin of bankers, shippers and traders; the outrageous uprising in the Taiping revolution which although based on religious affairs, had signs of violent hostility against the Manchus; and finally, the humiliating defeat in the Sino-Japanese war in 1894 which as stated by Pessanha, finally removed the fashionable yellow peril.

According to Venceslau de Morais, Japan exposed China to the world, showing the very poor conditions of its populace and the infamous opulence of its nobility, discredited and turned into an easy prey by the blond European who would soon humiliate it.

In a preface to Dr. Morals Palha's Esboço crítico da civilização chinesa, Camilo Pessanha gives an account of priceless historical, juridical, literary and cinematographic value. In fact, Pessanha's language is a visual and pictorial language which unlike poetry, carries us quickly and realistically to the effervescent Canton at the turn of the century:

Usually, my tours featured these spots, the Nam-Hoi court; (...) and in the suburbs an alley referred to in the tourist maps as an execution ground.

Inside the court, a huge ground floor like all 'yamens' or Chinese public buildings, and like all the others, empty and dirty, the arrangement follows that of our churches. In the place corresponding to the high altar, there is a small table covered in red cloth at which the district judge or 'chi-un' very seldom sits. I have never seen him there... At the sides there are similar tables for assistant judges and advisors, who on behalf of the district mandarin prepare all prosecutions. These are really very simple since they deal only with questioning. If the defendant confesses, they sentence his beheading; if he pleads not guilty, he is "taken care of" until a conclusion is reached. In view of this, most defendants plead guilty. I have attended many of those trials. The assistant mandarin, a fluffy noble wearing dirty clothes, presided over the session in silence. Next to him, the interpreter questioned the defendants (the many dialects make this officer indispensable) and the clerk took all the necessary notes. The defendant, carrying heavy chains on the neck, wrists and ankles, knelt down over his hands. Defendants were no longer human; they were just things, miserable rags covered with mud and dirt. They seemed to be taken from the awful sewage system. Their hands, the skinny and fragile hands with entwined fingers looked like dead arachnids. Anybody who witnesses such a thing will never forget it...

At one stage, some scoundrels started to move quickly, bringing benches, boards and bamboo poles and disposed of them in accordance with a plan (...) I realized quite naturally who those scoundrels were. According to the Sinologists they were the satellites: bailiffs, panderers, executioners, in a word the court parasites. One of the miserable human beings lying on the floor was brave enough to plead not guilty, and was of course to be tortured. It was about time for me to leave.

Likewise, his accounts of the pain inflicted at the execution ground are beyond what the Western sensibility can take.

In addition, Pessanha wrote some symbolic poems describing violent scenes in prisons which turned 'wild beasts' into 'quiet, mute and contemplative beings':

According to Venceslau de Morais, Japan exposed China to the world, showing the very poor conditions of its populace and the infamous opulence of its nobility, discredited and turned into an easy prey by the blond European who would soon humiliate it.

In a preface to Dr. Morals Palha's Esboço crítico da civilização chinesa, Camilo Pessanha gives an account of priceless historical, juridical, literary and cinematographic value. In fact, Pessanha's language is a visual and pictorial language which unlike poetry, carries us quickly and realistically to the effervescent Canton at the turn of the century:

Usually, my tours featured these spots, the Nam-Hoi court; (...) and in the suburbs an alley referred to in the tourist maps as an execution ground.

Inside the court, a huge ground floor like all 'yamens' or Chinese public buildings, and like all the others, empty and dirty, the arrangement follows that of our churches. In the place corresponding to the high altar, there is a small table covered in red cloth at which the district judge or 'chi-un' very seldom sits. I have never seen him there... At the sides there are similar tables for assistant judges and advisors, who on behalf of the district mandarin prepare all prosecutions. These are really very simple since they deal only with questioning. If the defendant confesses, they sentence his beheading; if he pleads not guilty, he is "taken care of" until a conclusion is reached. In view of this, most defendants plead guilty. I have attended many of those trials. The assistant mandarin, a fluffy noble wearing dirty clothes, presided over the session in silence. Next to him, the interpreter questioned the defendants (the many dialects make this officer indispensable) and the clerk took all the necessary notes. The defendant, carrying heavy chains on the neck, wrists and ankles, knelt down over his hands. Defendants were no longer human; they were just things, miserable rags covered with mud and dirt. They seemed to be taken from the awful sewage system. Their hands, the skinny and fragile hands with entwined fingers looked like dead arachnids. Anybody who witnesses such a thing will never forget it...

At one stage, some scoundrels started to move quickly, bringing benches, boards and bamboo poles and disposed of them in accordance with a plan (...) I realized quite naturally who those scoundrels were. According to the Sinologists they were the satellites: bailiffs, panderers, executioners, in a word the court parasites. One of the miserable human beings lying on the floor was brave enough to plead not guilty, and was of course to be tortured. It was about time for me to leave.

Likewise, his accounts of the pain inflicted at the execution ground are beyond what the Western sensibility can take.

In addition, Pessanha wrote some symbolic poems describing violent scenes in prisons which turned 'wild beasts' into 'quiet, mute and contemplative beings':

Na cadeia os bandidos presos!

O seu ar de contemplativos!

Que é das feras de olhos acesos?!

Pobres dos seus olhos cativos.

Passeiam mudos entre as grades,

Parecem peixes num aquário.

- Campo florido das Saudades

Porque rebentas tumultuário?

Serenos... Serenos... Serenos...

Trouxe-as algemados a escolta.

-Estranha taça de venenos

Meu coração sempre em revolta.

Coração, quietinho... quietinho...

Porque te insurges e blasfemas?

Pschiu... Não batas... Devagarinho...

Olha os soldados, as algemas!

In the poem entitled 'Branco e Vermelho', the poet featured the endless caravan of subjugated men:

Na areia imensa e plana

Ao longe a caravana

Sem fim, a caravana

Na linha do horizonte

Da enorme dor humana,

Da insigne dor humana...

A inútil dor humana!

Marcha, curvada a fronte.

Até o chão, curvados.

Exaustos e curvados,

Vão um a um, curvados,

Os seus magros perfis;

Escravos condenados,

No poente recortados,

Em negro recortados,

Magros, mesquinhos, vis.

A cada golpe tremem

Os que de medo tremem,

E as pálpebras me tremem

Quando o açoite vibra.

Estala! e apenas gemem,

Palidamente gemem,

A cada golpe gemem,

Que os desequilibra!

Sob o açoite caiem,

A cada golpe caiem,

Erguem-se logo. Caem,

Soergue-os o terror...

Até que enfim desmaiem!

Ei-los que enfim se esvaiem,

Vencida, enfim, a dor...

Outstanding and short, full of symbolism, featuring various rapid meanings and surrounding musicality. It was an intimate work, the purest and most mature creation of Portuguese symbolism.

^^ INTERROGAÇÃO

Outstanding and short, full of symbolism, featuring various rapid meanings and surrounding musicality. It was an intimate work, the purest and most mature creation of Portuguese symbolism.

^^ INTERROGAÇÃO

Não sei se isto é amor. Procure o teu olhar,

Se alguma dor me fere, em busca de um abrigo;

E apesar disso, crê! nunca pensei num lar

Onde fosses feliz, e eu feliz contigo.

Por ti nunca chorei nenhum ideal desfeito.

E nunca te escrevi nenhuns versos românticos.

Nem depois de acordar te procurei no leito

Como a esposa sensual do Cântico dos cânticos.

Se é amar-te não sei. Não sei se te idealizo

A tua cor sadia, o teu sorriso terno...

Mas sinto-me sorrir de ver esse sorriso

Que me penetra bem, como este sol de inverno.

Passo contigo a tarde e sempre sem receio

Da luz crepuscular, que enerva, que provoca

Eu não demoro o olhar na curva do teu seio

Nem me lembrei jamais de te beijar na boca.

Eu não sei se ê amor. Será talvez começo...

Eu não sei que mudança a minha alma pressente...

Amor não sei se o é, mas sei que te estremeço,

Que adoecia talvez de te saber doente.

Floriram por engano as rosas bravas

No inverno: veio o vento desfolhá-las...

Em que cismas, meu bem? Porque me calas

As vozes corn que há pouco me enganavas?

Castelos doidos! Tão cedo caístes!...

Onde vamos, alheio o pensamento,

De mãos dadas? Teus olhos, que um momento

Prescrutaram nos meus, como vão tristes

E sobre nós cai nupcial a neve,

Surda, em triunfo, pétalas, de leve

Juncando of chão, na acrópole de gelos...

Em redor do teu vulto é como um véu!

Quem as esparze -quanta flor-, do céu,

Sobre nós dois, sobre os nossos cabelos?

I hope that I will be able to take at least half, if not the full amount from some of them. </I>

</p>

<img src=)

Facsimiles of the case mentioned: cover, first page and last page signed by Camilo Pessanha.

For the first time, Pessanha was appointed Assistant District Judge in January 1899, and Property Registrar the following month. However, he took over the posts only on June 23rd, 1900. (5)

In 1904, magistrate Camilo de Almeida Pessanha, acting judge, was subjected to slander by two lawyers, Luís Gonzaga Nolasco da Silva and Manuel da Silva Mendes, who accused him of relaxing his duties towards the justice services, against which they submitted the relevant complaint to the Governor of the Province.

Four Chinese defendants were accused of stealing by the Royal Attorney General, and as the holder of the post was unable to carry out the proceedings, Judge Pessanha appointed Luís Gonzaga Nolasco da Silva as 'ad hoc' prosecuting council's agent by the judge. He took over the job and requested that stolen objects be checked by experts and witnesses interrogated. Even though there were various people arrested, the judge did not act as fast as he was expected and the prosecuting council's agent released the defendants, since fifteen days had elapsed from the date they had been arrested. Judge Pessanha replied as follows: The respect I have for your opinion notwithstanding, I am not able to accept your request. The defendants are not accused of theft, but robbery instead, which according to the previous legislation was called violent robbery. In this case arresting without proven offence is accepted.

As far as I understand and except otherwise stated, in the mentioned article of the New Reform, article 988 shall not apply to Macau and the provisions fixing a maximum of fifteen days for a defendant to be kept in prison without trial, since the defendants are Chinese. The law does not set out any limits on the number of times a person can be arrested for the very same crime. Otherwise it would be absurd, as the same arrest following mere accusations or hints calls for the continuation of the custoday until the accusation or hints have been proven unfounded. Furthermore, releasing prisoners and rearresting them for eight or fifteen day periods would only worsen the prisoners condition. Unfortunately, the preliminary instructions for the prosecution have yet to be finalized, due to the work-load of this court, which is also slowing down all affairs related to this case. However, that is meaningless. The special conditions affecting the colony justify that defendants be kept in prison until the trial takes place. The pro secuting council should be informed of this, but in the meantime the case shall be reopened.

Unhappy with this decision, Luís Gonzaga Nolasco da Silva appealed to Goa's Court of Appeal. He provided a comprehensive account of the affair and strongly opposed the judge's reasoning:

Sir! This was a case of negligence and disrespect for the court. Like these, many other people remain in prison without proven guilt. Less than a month ago some twelve prisoners petitioned for their release, based on the same reason, and God knows how many more are waiting for their cases to be resolved. The judge should not justify this for lack of time. It is lack of work, it is negligence and disregard for other people's rights (...) The negligence is such that some lawyers filed a complaint against the judge, which was given to the Governor of the Province to be passed to His Majesty.. The most significant complaints against the judge were:

A defendant was found not guilty, but he had to remain in prison because the judge forgot to sign the relevant release papers. Many criminal sentences are just pencil-written and unfounded notes, on the back of files; besides, some of the files have been closed without any remarks. Also ordinary sessions have no fixed time and sometimes they do not take as long as is required by law.

Sir! These and other anomalies by the Macau Court have been putting the good name of Portugal at stake, as well as damaging the reputation of the judicial authority. Therefore, it is necessary to finish with this state of affairs because as the prosecution council's agent I will not tolerate this any longer. Although the accused may be Chinese, nevertheless individual freedom should be respected and the law should also be respected, without any sophisms or fake interpretations(...).

Camilo Pessanha (second row, far left) in a group of teachers and pupils of the Macau Lyceum. Also visible are Silva Mendes, Luís Gonzaga Gomes and António Conceição.

Judge Pessanha wrote the following concerning the above-mentioned complaint:

Sir! I will keep my decision. I feel that the appeal against my decision is an accusation against the judge. The same accusation was apparently submitted by two lawyers to the Governor of the Province. I have not been informed of that complaint and if it has ever been submitted, it should remain secret. It seems to me that one of the complainants is the prosecution council's agent himself and I will refrain from replying to that accusation (...).

The judge then explained his decision in accordance with his sincere interpretation of the law, stating that in the Ordinances in force when the Reform was published, there was no difference between theft and robbery; they were one of the cases in which property was removed from third parties and that was punished in accordance with the circumstances in which that had happened - it could be by force or violence against people, or by breaking-in which was violent (...) I know very well that courts have been focusing on a different spirit than the principle I defend in my decision. If my interpretation is not the best, the Court of Appeal shall correct it.

The Court of Appeal supported the appellant...

This small set-back and the heavy work load might have worsened Pessanha's poor health. In 1905 he arrived in Portugal so sick that he questioned whether he would be able to endure the return trip:

When I left Macau I had no hopes of reaching this place that I miss so much, to which my soul belongs (...) My bones belong to the unpleasant ground of my exile, thanks to an absurd and invincible fate (...)

Another file dated from 1909, which we have also looked into, consists of an appeal to the Goa Court; in this case, Camilo Pessanha was just the lawyer of those who lodged an appeal.

The motive of the appeal was the arrest of four people, three Portuguese and one Chinese, in accordance with a decision by the Registrar, acting Judge of the District Court, Augusto Carlos Afonso Marques (6). The prisoners were suspected of withdrawing from the Government Exchequer, operating in the Banco Nacional Ultramarino's branch in Macau, a total amount of $43,890.00 patacas by means of counterfeit public bonds.

In this allegation, he dismantled, logically and coherently, the whole process which was to become the 'case of the file'. Significantly enough, Camilo Pessanha called it 'Disorientation' and in the final summing-up he explained why he used this name. However, the Goa Court confirmed the accusation against the defendants and did not acquit them.

The final note was a violent accusation against 'the lack of the most elementary means of investigation in the Territory, which prevented any effective repression against criminality' allowing almost every serious crime to remain unpunished. More serious was the way people were condemned, based almost exclusively on evidence from witnesses, as there were no other means of additional investigation.

According to Pessanha, the solution would be the setting up of a Proceedings Court and the relevant ancillary bodies in order to dignify the image of justice in Macau, which was the only practical proof in the Far East of Portuguese culture and colonizing ability.

These are some excerpts of Pessanha's allegations: But there are other crimes, more serious than that of fraud, regularly committed in Macau which remain unpunished. However, no one seems to worry about this. In certain years, arson, a very serious crime, is very common; this one of the cases in which the law allows suspects to be arrested without proven guilt. Very seldom does the court takes notice of those arson cases and if so, very few cases are finalized. And above all, no arsonist has ever been found guilty and condemned in Macau.

Poisoning, a very common crime in China, is one of the worst crimes and very wisely all legislators consider it more serious than murder. It is believed that in Macau poisoning is also very frequent. However, statistics do not mention any case of poisoning. This crime can be detected only through a toxicological test and Macau lacks a proper laboratory and there is no way one can request such tests from any other laboratory. Therefore, poisoning is not referred to in statistics. (...) In view of the signs of torture that corpses show or other signs that give those corpses a disturbing aspect suggesting ritual mysteries, those homicides would cause a huge public uproar. (...) In Macau, they go unnoticed due to an affective and moral apathy which seems to be a general stupidity.

And what do the authorities do about it?

The Police Commissariat reports to the Court that a corpse has been found and presents two witnesses. The judge carries out a direct check and questions the witnesses, who in general neither know the victim nor anything about the crime: they were chosen because they were passing by when the police arrived.

After this, the file is kept in the Notary until new evidence is brought. It would be an interesting exercise to find out how many cases like those are still awaiting a decision. I am talking about crimes which have not become void because they have been committed within the last fifteen years, and those crimes which have become void, which have been committed within the ten years prior to that fifteen year period. Very seldom one is able to identify the victim, and to find out who the murderers are is even more rare. An exceptional case is when they are in fact arrested.

THE END OF THE END

In 1925, one year before his death, Camilo Pessanha was appointed acting principal of the High School, but a few months later he resigned from the post due to ill-health. The poet could now free himself from the fatal disease of not being able adapt to life; a life that through a very unpleasant fate divided him between two abysses so far away from each other.

The poet could now accept, with ironic distance and quiet apathy, the fate of all men:

Porque o melhor, enfim

É não ouvir nem ver...

Passarem sobre mim

E nada me doer!

Rixas, tumultos, lutas,

Não me fazerem dano...

Alheio às vãs labutas,

Às estações do ano.

E eu sob a terra firme,

Compacta, recalcada,

Muito quietinho. A rir-me

De não me doer nada.

He longed for his death, a sweet fainting which would take him to the immortal serenity of

'(...) céus claros e amenos

Doces jardins amenos,

Onde se sofre menos,

Onde dormen as almas.'(7)

Sleep at last, without desiring nor missing things that have been lost or not achieved.

This text was presented by the author in the Judgement Hall of the Macau District Court during a cultural event organized by the Macau Juridical Institute on November 23rd, 1988.

Photograph of Camilo Pessanha with his friends Carlos Amaro and José Pereira Martins taken during his last visit to Lisbon.

** The Ordenações Filipinas, named after Filipe I (who reigned between 1580 and 1598), were issued in 1603 and remained the basis of legal practise in Portugal until the introduction of the Civil Code of 1867.

NOTES

(1) Report of the Minister for Justice Affairs, Augusto César Barjona de Freitas, a preface to the proposal for the abolition of capital punishment which was submitted to the Parliament on June 18th, 1867.

(2) Eça de Queirós-in 'Geração de 70' - Dicionário de Literatura.

(3) Guerra Junqueiro - 'O caçador Simão' - Finis Patriae.

(4) História de Portugal by Joaquim Veríssimo Serrão - Vol. X (1890-1910) - Editorial Verbo.

(5) During this Conference, the Macau Juridical Institute gave us the opportunity to go through some of Camilo Pessanha's lawsuits. From these we have chosen two: one in which the poet takes part as acting judge and the other one as a lawyer. Currently, his juridical heritage is being put together, microfilmed and computerized under our guidance.

(6) In accordance with a decree dated February 28th, 1919, Camilo Pessanha, Properties Registrar of Macau, resigned from that post to which he was appointed on February 16th, 1899 (Government Gazette no. 22, dated May 31st, 1919).

(7) Quoted by Danilo Barreiros in O Testamento de Camilo Pessanha -Lisbon, 1961.

* Graduate in History (Coimbra University), teacher of Macau's History, researcher.

start p. 74

end p.