In 1253, Friar William of Rubruck was dispatched by King Louis IX and Pope Innocent IV to seek an alliance with the Mongols against the Moslems. From Friar William's travel book Itinerarium we have an account of his experiences during his travels. Another travel book worthy of note is that of Sir John Mandeville. This book, translated into many European languages and first appearing in Anglo-Norman French in 1356-7 and in English in 1375, is not only a geographical and cultural guide but also gives romantic and fantastic accounts of what Sir John witnessed on his travels. Undeniably, however, the most famous and reliable source is that of The Travels of Marco Polo. This book offered medieval Europe a glimpse of the strange and exotic world of the Far East as no other book had ever done before. It is with these great travellers in mind, then, that the reader can consider the work of Fernão Mendes Pinto entitled Peregrinação (Peregrination), an extensive work in Portuguese which was published in 1614, thirty one years after his death.

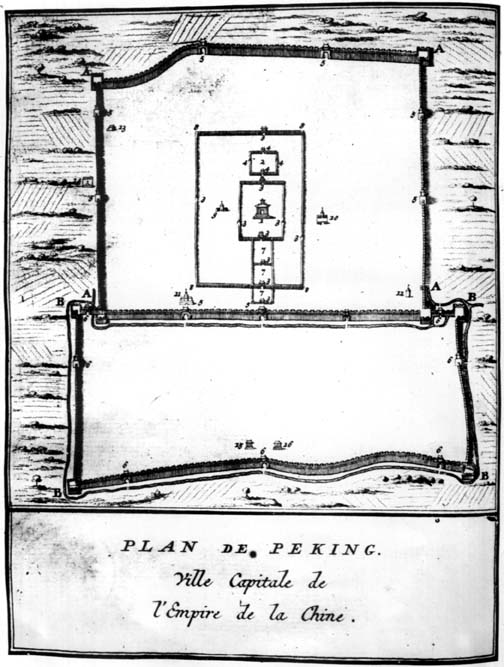

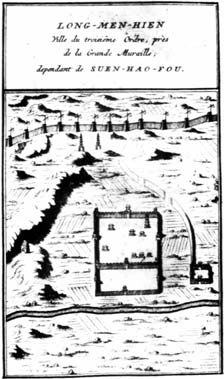

In J. B. Du Halde, 'Description.... de l'Empire de la Tartarie Chinoise' (Haye, MDCCXXXIV).

In J. B. Du Halde, 'Description.... de l'Empire de la Tartarie Chinoise' (Haye, MDCCXXXIV).

In his work Peregrinação, Fernao Mendes Pinto, as the representative of 15th century man, explores the cities of the East. He explores these cities on both physical and metaphysical levels. In this article, we are not looking for any limits of truthfulness in a positive sense. Neither will we try to identify any places where Fernao might have been. Our approach to this extensive work, which does not fit into any literary trend, will be based on the principle that as a literary work it has room for creativity, fiction and imagination. As a literary work featuring a journey as its main theme, it is the representation of a qualitative transformation caused by men, the agents of transformation and its driving force. Based on the above, we come to the conclusion that we are dealing with the transformation of the country man into the city man and that this change was brought about because the City was being sought, the aim of the journey being the discovery and definition of a City, not the unreal but the real City, even though it corresponded to the 'Mito de Megalópolis' (Megalopolis Myth) reported by Lewis Mumford in A Cidade na História, University of Brasilia.

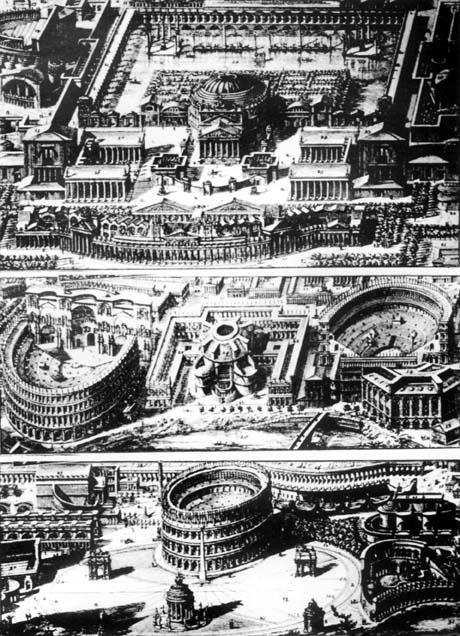

The megalopolis myth, as seen by Piranesi's urban-architectonic views - detail of 'Il Campo Marzio' by Piranesi (in 'The Imaginary Views', Miranda Harvey, Academy Editions, London).

The megalopolis myth, as seen by Piranesi's urban-architectonic views - detail of 'Il Campo Marzio' by Piranesi (in 'The Imaginary Views', Miranda Harvey, Academy Editions, London).

In fact, the feeling one gets when reading Fernão Mendes Pinto's complex, intricate and endless route is that only the City deserves to be described and observed. Jungles, forests, castles, fortresses, settlements and towns are just milestones on the way to the City of Peking (chapter 89): Going up the river we did not see any village, city or building worth mentioning in the first two days. However, there is a great number of towns and settlements of two to three hundred inhabitants along the river banks. From what we could see, these people seem to be fishermen whose lives depend on their own work. Inland, there were just huge pinewoods, chestnut trees, orange groves and cornfields, wheatfields, rice paddies, corn, millet, vegetables, flax and cotton (...) However, Fernão continues, delaying his progress only when he is forced to do so. His goal is the City.

Anticipating the conclusion, we could very well say that in Peregrination the Eastern, exotic City is both a metonym and and an icon, corresponding to an image which, through the experience transforms expectation into reference. In fact, having to face the foreigner from the other side of the world, from a nation so remote that so far no book or account has ever made any reference to our name, nobody understands our language, the Oriental functions in absentia, building an image which he can only grasp through dialogue. The Oriental will learn only what the European is willing to tell him and he has no means of checking it. His knowledge is therefore limited by the informants, by their interest or strategy, as a means of self-defense or of accomplishment of their goals. One example among many is as follows (chapter 4): (At Fumbau settlement) we went with Anrique Barbosa and forty Portuguese to the place where the princess lived (...) She told us to sit down on some mats (...) and asked us (...) about new and curious things (...) and the power that the King of Portugal held in India, how many fortresses there were (...) and what countries they were in as well as other similar things. The account adds that she seemed to be pleased with our answers.

On the other hand, the European will act in praesentia. This will favour the process of analogical thought which shapes both similarity and dissimilarity. In Peregrination the subject thinks analogically and analogy is used to bring Reality closer. This approximation can come up as a metamorphosis due to either hyperbole or to euphoric or dysphoric effects.

In fact, it might be said that analogical thought remains in the narrative and descriptive language of Peregrination where we can very often find sets of similarities based on analogies:

'Reconstructions of Pantheon and Baltus Marcelus and Statilius Taurus Theatres'; Il Campo Marzio, Piranesi.

'Reconstructions of Pantheon and Baltus Marcelus and Statilius Taurus Theatres'; Il Campo Marzio, Piranesi.

1 - Linguistic, shown by expressions such as which means, which in our language means, and so forth;

2 - Economic values, giving exchange rates of currencies, namely in relation to the cruzado;

3 - Dignitaries and ranks: Indian priests who (...) are like Capuchin friars, the chifun was the mayor; whipping men who are like our torturers or police agents';

4 - Institutions: 'Each one of these prisons has one institution that gives them assistance, like the Misericórdia, which helps the poor;

5 - Social events, banquets, ceremonies, meals, plays, parties, etc;

6 - Religious rituals and institutions: hell, devils, churches, etc;

7 - Aesthetic, ethical and cultural values;

8 - Greatness, spaces where the concept and image of the City is included;

According to Gilbert Gadoffre ('Analogie et Conaissance', page 48) À la Renaissance on part des rapports constatés entre les éléments d'un groupe, on les compare avec ceux qui existent dans un autre groupe et si les deux systèmes de rapports sont semblables (ou équivalents) on parle alors d'analogie. However, based on mechanisms of analogy, he describes the City according to a hypertrophic paradigm, the image of desire which morphology has created by itself, when he refers to Peking: This City of Peking, a metropolis like any other in the world with its grandeur, police, wealth and so forth.

. </figcaption></figure>

<p>

<I></I>From chapter 95 we may conclude that to Fernão Mendes Pinto the grandeur was the most fluid morphological element which characterized the City. He can therefore speak of large cities like Peking and Nanking and of small cities like Pacão and Nacau. However, he does not distinguish cities by their grandeur. That distinction is made with other settlements according to the following hierarchy: cities, towns, villages, settlements, fortresses and castles (chapter 91). Besides its grandeur, the City is the place where power rests. Still far from Peking, calling at Hainan island, an Oriental offers him the following advice which made him very curious (chapter 45): <I>If you are surprised with this, which is small in size, what will you say when you see the city of Peking where the Son of the Sun lives with his court? </I> The place where the power lies is of course the place where aristocracy lives. People are related to the grandeur of buildings, yet one more element that integrates the urban morphology. Upon arrival at Pacão and Nacau (chapter 92) he emphasizes the aristocracy: <I>(Pacão and Nacau), both small yet noble. </I>In chapter 97, upon arrival at Inquinilau he stated that: <I>It is a large, wealthy city with many things and noble people riding horses and walking. </I>Regarding aristocracy and grandeur, he made the following comments: <I>All these aristocratic streets feature arches at every entrance with doors that are closed at night, most of them having fresh water fountains </I>(chapter 88)... The city is also a complex body, where political, administrative, economic and religious bodies are related to each other. It is here that all human resources are mobilized and all surplus is collected and kept. There one can find <I>the Cãs, Anchancis, Aitaus, Tutões and Chumbis, people who rule provinces and domains </I>(chapter 88). In the City one does not live only for work as in the village referred to earlier. Quite the contrary, the city collects all surplus wealth and translates it into grand monuments, buildings and spectacular houses. It is also the meeting point of an exogenous population and therefore a cosmopolitan environment as described in the following excerpt: <I>Large fairs filled with people from various regions and abundant supplies. </I>On the other hand, work is not just a matter of survival, on the contrary, it covers industrialized work which leads to large scale organized trade: <I>The city (Nanking) had ten thousand silk looms. </I>Still in chapter 90: <I>In Xinligau and in another city five leagues up north, most of China) Such accumulation of surplus wealth is the reason behind the city's grandeur and ostentation and that is why it featured very tall towers of six and seven floors in size with gilded spires. In these towers they store their weapons, ammunition and treasures as well as their silk and very rich items such as fine porcelains. (chapter 88).

Such accumulation of surplus wealth is the reason behind the city's grandeur and ostentation and that is why it featured very tall towers of six and seven floors in size with gilded spires. In these towers they store their weapons, ammunition and treasures as well as their silk and very rich items such as fine porcelains. (chapter 88).

However, in addition to the elements that shape the city on the inside i. e. its grandeur, police, wealth and abundance, there is one factor that marks the existence of the City as a sociocultural body: it is the wall which protects the Ctiy from outside. While describing Nankin, which seemed to be the preview to the metropolis (Peking), Fernão Mendes Pinto, after locating the city and assessing its size ( eight square leagues), distinguished one or two storey houses' from aristocratic houses, Featuring a wide range of ornaments on their roof spires (...) All in all showing grandeur', he pointed out the wall: The city is surrounded by a wide and well built wall with one hundred and thirty doors and bridges over basements. Thus the City is an enclosed area, protected and secure since Each door had a doorman with two archers to check every entrance and exit. He added that It features 12 fortresses, similar to ours, with bastions and very tall towers.

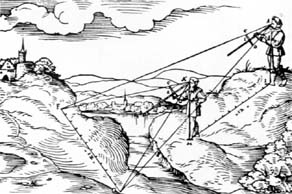

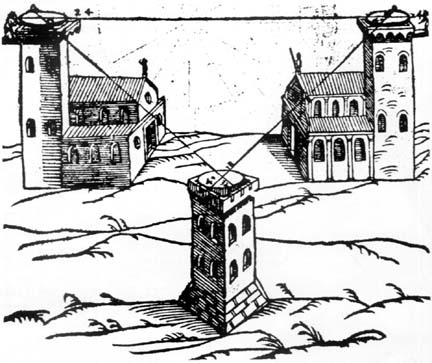

How to draw the plan of a city with a compass (drawing taken from a study by the most important humanist architect, Leo Battista Alberti, mid 15th century).

The description of this wall and its fortifications is paradigmatic and defines the City in itself. Cities may vary is size and wealth: there are large and small cities, good and not so good. However, they are all protected by fences. As regards the small city of Mindoo, Fernão reported that on the section towards the jungle, there was a salt water lake (chapter 96). Salt water which was not drinkable therefore turning it uninhabitable. The wall is the prime element that distinguishes the city from a village, as this features no wall. According to Fernão, the wall also marked a difference between the city and the town, as the latter featured a wall without any fortification or protection. In chapter 90, Fernão stated that After we left these fields behind, ten to twelve league fields, we reached a town called Iunquileu, surrounded by a brick wall with spikes on top but without battlements, bastions or towers.

Enclosing a space defines demarcation between an organized or cosmic space in accordance with Mircea Eliade's terminology, and the exterior chaotic space. The protecting wall serves as a reminder that exterior forces wish to invade or fall upon the City, protected on the inside in order to keep its stability. Eliade identifies the sacred space, the temple and the palace as the centre of the world: La cloture, le mur ou le cercle de pierres qui enserrent I'espace sacré comptent parmi les plus anciennes structures architectoniques connues des sanctuaires. He added that Il en va de même des murailles de la cité: avant d'être des ouvrages militaires, elles sont une défense magique, puisqu'elles reservent, au milieu d'un espace chaotique, peuplé de démons et de larves (...) un espace organisé, cosmisé, c'est à dire, pourvu d'un centre (Traité des Religions, p.318).

Souchao, featuring its walls, temples, pagodas and buildings (picture taken from a book by J. B. Du Halde).

This is why, throughout Fernão's long journey in search of the City or cities, all of them correspond to the enclosed space paradigm. Let us see a few more examples: On the fourth day of our journey we arrived at a city called Pocasser, twice as big as Canton and surrounded by a very strong brick wall with towers and bastions similar to ours (chapter 89). We left this city the day after (...) We then arrived at another city, this one was Xinligau, which was also very large, with fine houses and surrounded by brick walls. At their ends there were two strong fortresses with towers and bastions, like ours, and drawbridges at the entrances (chapter 90). However, this space could not be isolated from the rest of society. On the contrary, the wealth, commerce and life of the city dictate that it cannot be isolated from those outside influences which contribute in a positive way to the life of the city. For example, Nanking had one hundred and thirty city gates with bridges over moats. As with all other cities, all movements were carefully checked. The description of this wall and its fortifications defines the city and is paradigmatic. Cities may vary in size and wealth. There are large and small cities, some good and others not so good. However, they are all protected by fences. As regards the small city of Mindoo, Fernão reported that on the section towards the jungle, there was a salt water lake (chapter 96). Salt water, being undrinkable, therefore made the city uninhabitable. The wall is the prime element that distinguishes city from village, and this featured no wall. According to Fernão, the wall also marked a difference between the city and the town, as the latter featured a wall without any fortification or protection. In chapter 90, Fernão stated that after we left these fields behind, ten to twelve league fields, we reached a town called Iunquileu, surrounded by a brick wall with spikes on top but without battlements or towers. In the case of the city of Peking, where the crystallization of the imagination develops along the Peregrination until a climax is reached, features not only one wall, but is enclosed by two very strong brick walls with three hundred and sixty doors. On each door there is one castle with two very tall towers, houses and drawbridges. Paradigm, hyperbole, metonym and icon, Peking arises, with its grandeur and civilization, wealth and abundance, to the admiration and amazement of the naive observer, keen to absorb difference and disproportion. The preface to the description of Peking is worth recalling: This city of Peking of which I promised to provide more information than I have got so far, is so grand that I almost regret the promise I made. I do not really know where to start, because it is not like Rome, Constantinople, Venice, Paris, London, Seville, Lisbon or any other European city. Nor does it look like any other city that I know of in the world. Perhaps I dare say that no other city can be compared to this huge Peking, with its grandeur and sumptuousness featured in its buildings, wealth, abundance, (...) people, customs, vessels, justice, government and peaceful Court (chapter 107).

It is the true image, or according to Lewis Mumford, the 'Myth of megalopolis', perhaps the final stages of the urban development representing the hyperactivity of human concentration, thus creating metropolitan model patterns.

This perception of the city seems to encapsulate Fernão Mendes Pinto's search. It is also interesting to note that Peking occupies the centre stage in this novel of desire and knowledge. Until Mendes Pinto reaches Peking the reader is swept along on an upward curve of expectation. After Peking, the curve descends slowly until it comes to rest in Almada, not a city, but a town in Portugal where we conclude our unfinished search.

In J. B. Du Halde, 'Description... de I'Empire de la Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise' (Haye, MDCCXXXIV).

* Professor at the Social and Human Sciences Faculty of Lisbon's New University

start p. 66

end p.