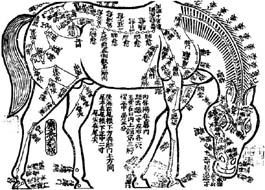

Engraving of a diagram of the horse showing its acupuncture points.

Engraving of a diagram of the horse showing its acupuncture points.

Taken from The Chinese Repository, vol VII, December, 1838, N°8 - Article I. "Notices in Natural History: 1, the ma or horse"

Seventeen pages of the Pun Tsaou are filled with an account of the horse, treating of the uses of the various internal and external parts of his body in medicine, and the mode of their exhibition in diseases. The manner in which the subject is here treated affords a good instance of the usual order pursued by the compilers of that work, in their descriptions of the numerous articles included in Chinese materia medica, - and we will for once follow them, as well to show our readers this order, as to tell them what the Chinese say of that favorite and noble animal. To do this, it will not, however, be necessary to enter into all their minutiae regarding pills, boluses, &c., but simply to give the principal points under each section.

Sec. I

"Name explained. Le Shechin says, 'Gan Heu remarks, the horse is a warlike animal; the character ma represents its figure, head, mane, tail, and legs'. What was originally written, in outline thus , is now reduced to馬, ma. Different names are applied to stallions and mares, and to colts of various ages and colors, which are very numerous; for which see the Urh Ya.

, is now reduced to馬, ma. Different names are applied to stallions and mares, and to colts of various ages and colors, which are very numerous; for which see the Urh Ya.

Sec. II.

"Gan King says, 'There are horses of many colors, but for medicine the pure white is the best; though if the animal has a few spots, as in his eyes, mouth, and hoofs, they need not be regarded'. Le Shechin says, 'Wild horses are found in Yunnan and Shanse; generally speaking those found in the north and west are superior to those in the south and east, which are small and weak. The age is known by the teeth, which at first are small, but increase as the animal grows older. Its eye reflects the full length image of a man. If he eats rice, his feet will become heavy; if rats' dung, his belly will grow long; if his teeth be rubbed with dead silkworms or black plums, he will not eat, but this is removed by rubbing them with mulberry leaves; if the skin of a rat or wolf be hung in his manger, he will not eat. He should not be allowed to eat from a hog's trough, lest he contract disease; if a monkey is kept in the stable, he will not fall sick'.

Sec. III.

"The flesh of a pure white stallion is the most wholesome; if it is bitter or cold it is noxious". Many authors are quoted with regard to the wholesomeness of horseflesh, whose opinions differ. One says, "that those who eat the flesh of diseased horses, nine out of ten die; it should be roasted and eaten with ginger and pork". Another remarks, "To eat the flesh of a black horse and not drink wine with it, will surely produce death." Le Shechin recommends eating almonds, and taking a rush broth, if one feels uncomfortable after a meal of horse-flesh. - It may here be added, that we have seen this article of food for sale in the shambles of Canton, and it is probably eaten more frequently in the northern provinces than in this region.

VOL. VII N°. VIII.

Sec. IV.

"The fat lying on the top of the head is sweet, and unwholesome in only a slight degree. It will cause the hair to grow; brighten a dark visage, and cure flabby skin on the hands and feet." It is a general principle in Chinese pharmacy, of which this is an illustration, that any part taken from an animal affects the same part in the patient.

Sec. V.

"Le Shechin says, 'In the Han dynasty, a spirit was made from mare's milk'. The milk is sweet and cooling; when made into kumiss its nature is bland; and drinking it reduces the flesh.

Sec. VI.

"The heart of a white horse, or that of a hog, cow, or hen, when dried and rasped into spirit, and so taken, cures forgetfulness: 'if the patient hears one thing he knows ten.' "

Sec. VII-VIII.

The lungs, and liver, are here described, "The liver is very poisonous. Woote of the Han dynasty says, 'When eating horse-flesh, do not eat the liver.' 'He who eats liver of a horse will die,' says another." The Chinese ascribe the noxious properties of the liver to the want of a gall-bladder, which is known to be wanting in the anatomy of the horse. The gallbladder they suppose to be the seat of courage; and in ridicule say to a poltroon, "I'll send you to buy a horse's gall-bladder." In Kanghe's dictionary there is a mode of demonstrating the noxious properties of a horse's liver, peculiarly Chinese: "The horse corresponds to fire, and as fire cannot produce wood, (which is the province of water,) therefore the horse has a liver without any gallbladder; and as the gallbladder is the effluence of wood, (which corresponds to the liver,) and is not complete in the liver, therefore if one eat it he will die."

Sec. IX-XI.

"The kidnies," says Le Shechin, "contain an inky fluid which is allied to the bezoar of the cow, and calculi of the dog, but its properties were unknown to the ancients." The placenta of the colt as a remedy in obstructed menstruation.

Sec. XII.

"Above the knees, the horse has night eyes (warts), which enable him to go in the night. They are useful in the toothache".

Sec. XIII.

"The teeth and grinders are to be burned to ashes, and if mixed with spittle and administered to children, the dose will cure their shivering fits".

Sec. XIV-XVII.

"The bones of the body, head, and legs, and the hoofs are efficacious." "If a man is restless and jolly when he wishes to sleep, and it is required to put him to rest, let the ashes of a skull be mingled with water and given him, and let him have a skull for a pillow, and it will cure him." The same preservative virtues appear to be ascribed by the Chinese to a horse's hoof hung up in a house, as were supposed by our ancestors to belong to a horse shoe when nailed upon the door.

Sec. XVIII-XX.

"The skin of a bay horse will hasten delivery." The mane and tail are useful.

Sec. XXI-XXIV.

The brains, blood, perspiration and excrements, are prescribed; the first three are highly poisonous. "Whoever has any of the blood of the living horse enter his flesh, in one or two days it will become a large swelling, and gradually joining his heart, kill him; if in cutting a horse, he wounds his hand, and the blood enters his flesh, that same night he will die."

In this manner are the various subjects, treated of in the Pun Tsaou, discussed; and by means of general indices, and the use of different sizes of type, the student can quickly refer to any topic he is investigating, Wild horses are said to exist in Kansuh and Leaoutung, and also beyond the western frontiers; they are smaller than the domesticated animal. The skin is in demand for making garments, and its flesh (so the Chinese say) has the same flavor as that of the common horse.

Although the Chinese cannot be said to have carried the culture of the horse to very high perfection, judging from the sorry looking ungroomed, animals, with large knots in their tails, which we see in this part of the empire, still they have not entirely neglected the veterinary art. We have now lying before us in the Ma King a work in four volumes octavo, containing about 400 pages entirely devoted to this subject; the treatment of the camel and cow is appended in a fifth volume. The work was written in the first part of the 17th century, in the reign of Wanleih, by the brothers Yu Yuen and Yu Hing; and afterwards corrected by Tung Ke. It contains 112 plates, 150 songs, and directions for making 300 prescriptions. It is divided into four parts. The first part consists of 12 essays and as many metrical pieces, explaining the mode of feeling the horse's pulse, which is placed in his breast; describing the different parts of his body; and giving the accounts concerning him transmitted from antiquity. The writers have sometimes chosen the form of poetry to convey their researches, and many of the essays are thrown into the form of conversation, in order to enliven a dull subject. The second part gives the diagnosis of the seventy-two diseases to which the horse is subject, comprising directions how to ascertain what part is affected from the pulsations. The third part contains eight sections on the eight states of health (as cold, hot, empty, solid, &c) of the horse, with plates illustrative. There are also reports of 74 conversations held between Tung Ke the correcter, and Yu Yuen the author, concerning the mode of treatment to be pursued when the symptoms were thus and thus; and the reasons for certain peculiarities about the horse. The fourth part describes the kinds of food he should have, among which pulse, grass, grain, tea, soup and water are mentioned; and the whole concludes with directions for compounding the medicines and the mode of administering them.

We have time only to give this author's criteria of a good horse, but should think from the hasty examination of its contents that the Ma King might afford some interesting notices to one well acquainted with the veterinary art. "There are thirty-two marks, of all which the eye is the pearl; next you must see if the head and face are proportionate, but he who wishes to know how to distinguish a good horse, and does not examine the books of former ages, is like a blind man going in a new road. The eye round as a banner-bell, color deep; pupil bean-shaped, well defined, with white striae; iris with five colors, - he will be long-lived: nose with lines like the characters kung and ho,-he will see forty springs: the forehead higher than the eyes; mane soft with ten thousand delicate hairs; face and chops without flesh; ears like a willow leaf; neck like a phoenix's, or cock's when crowing; mouth large and deep, with lips like a box close joining; incisors and molars far apart; tongue like a two edged sword and of good color; the gums not black, - he will have long life: lean as to flesh, fat as to bones; never starting at sounds nor fearful of sights; the tail elevated is reckoned a good sign; head inclined and neck crooked, with three prominences on the crown; sinews like a deer's; bones of legs small, and hoofs light; fetlocks shape of a bow; breast and shoulders broad, but little projecting forward; head long and loins short; belly hanging, and the hair on it growing upward; hoofs strong and solid; knees high and joints uniform; flesh on the back thick, making it round as a wheel; scapula like a pe-pa, and femur inclined; and tail like a flowing comet, hairs all soft." Such the Chinese give us as the principal characteristics of a good horse.

start p. 24

end p.