"In the afternoons, when, after intense work, the muscles in my body could no longer benefit from an invigorating game of tennis, I used to go to the poet's quarters in search of spiritual refuge."

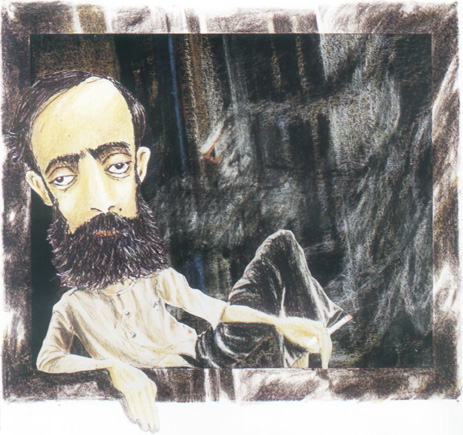

"The poet was always at home at that hour, lying in his bed. He spent whole afternoons like that, only going out very occasionally. Once the door opened, you went through the two entrance halls and then turned sharp right to reach his room. Then you pulled back the door curtains and through the yellowed grill saw the dreamer's black beard and tiny bright eyes."

"The poet lay there in his simple clothes, like a fakir or an Indian mystic, saying "Come in, come in!" in a voice feeble yet with sharp crescendos. I would pull up a chair next to him and the dogs which had followed me would leap on and off the bed like clowns in a circus. However, it was always his favourite, Arminho, who succeeded in chasing off the others and positioning himself in his unchallenged spot next to his owner, on his legs or by his head licking his hair. That was how he slept at night.

Pessanha would be reading and smoking at that time of day, dressed in a short vest, his cigarette-burnt sheet barely covering him. Nearby stood the bedside table, its fittings recently silver-plated in the workshop of a friend (unworthy of his friendship) in eager, meagre gratitude for getting him out of some legal problem. On top of the table, a lamp, a pipe and a tin of opium. Beside it, a small chair loaded with books. Hanging over the headboard, crowned with a duke's coronet, were two fantastic tin fish. An old rosary hung from the headboard which, with tears in his eyes, the poet told me had belonged to his late mother and which he always had by him. It was the dearest souvenir of a soul which had wandered through life, "begging at the door of matrimony".

"This was the atmosphere in which Camilo Pessanha received his visitors.

We would talk of a plethora of things: history, Chinese art, poetry and our own times were our favourite subjects. Pessanha rattled on, hardly letting his companions make any comments or offer their opinions. He repeatedly cleared his throat as he spoke and gave out short laughs, exposing the black mouth of an opium smoker, a revolting, cavernous abyss.

From time to time the parrot next to the window would screech in unison with him while he continued his perorations or made some acid remark about life and men. His heart, like that of all of us, was light cast with shadows and there was some truth in his reputation as a 'razor tongue'. Once, when we were talking about the merit of the newer and older generations of poets, there wasn't a single one who came up to scratch."

"He was not averse sinking to the level of the local intrigues and scandals in that moral cesspit. That honest man (who had never sought after money) and who could have been a millionaire had he so desired had neither time nor forgiveness for those Portuguese who sold their soul and the honour of their nation for a few thousand patacas."*

"The horror he felt at the deaths in the revolutionary strike of 1922 can naturally be explained by his excitable nature as he rejected all forms of violence."

"After these artistic diversions, we would go back to his room. As the evening drew in, the poet's energies would fade and his gaze would grow weak. He was missing something, the stimulant on which his life now depended. On my first visits, he still kept up some pretence; later on he just apologised, rang the bell for his Chinese concubine and asked her to prepare his opium. The honey-coloured ball passed thrice over the flame of the lamp: three pipefuls. The poet drew on each, finishing it in two or three puffs, not in a single draught like the adept Chinese smokers.

I was watching a scene out of de Quincey or Claude Farrère. Then he would come out of his torpor, regaining his lucidity and vivacity, his nerves coming to life once again: more words, more ideas, more fire."

"At the same time every afternoon (and once every morning so they told me) he partook of his three lumps of opium, a moderate amount compared to that smoked by Orientals and one which cost him a hundred patacas per month. His Chinese friends knew that his favourite present was a few tins of the drug and they would occasionally send him some from the "Macao Opium Farm", the most famous, sought-after opium.

He almost always spoke Chinese in a lively voice with his Chinese companion during this operation and took up the conversation with me later on. His face was weather-beaten, opium-drawn, his eyes deep-set, his gaze strangely mad, making him resemble a Greek poet incarnate re-telling the legends of his age. When he recited Chinese poetry he had translated, dream almost became reality. He was a ghost declaiming messages as deep and old as the world.

Arminho would alternately stretch himself out indolently or sit up and stare at us questioningly, rather like the ceramic lions which guard the Buddhas in the temples. No doubt his genealogy might have provided the answer to this resemblance.

When he accompanied Pessanha to school, he would lie under his table and yawn at the endless speeches proffered by the ad hoc historian. When lunchtime drew near, he still wouldn't move: loyalty won over hunger."

Sebastião da Costa

Seara Nova, Nova, nº 85, April 29, 1926

Illustration by Carlos Marreiros (fragment)

Illustration by Carlos Marreiros (fragment)

"Camilo Pessanha, school teacher and brilliant advocate in the halls of this county, was, effectively, a scintillating, irreverently caustic spirit who took delight in a sardonic, sneering mordacity. He was the victim of a dreadful physical anguish which undermined his sickly existence and the deathly effects of opium which he smoked to excess. Hostage to his art too, his was a tortured soul which was bound by a desire to attain perfection, always seeking that which merited publication. This meant he felt obliged to score out, correct, erase, recuperate and rework the same poem countless times which resulted in the deplorable shortage of works written by him."

Luís Gonzaga Gomes

Notícias de Macau, February 11, 1962

"The central figure in this triptych was the poet Camilo Pessanha, a strange and popular figure in this Colony where he spent a large part of his life. He likened it to a caricature of himself: squat, skinny, appallingly skinny, his frame bowed down, his legs giving way at the knees, dragging his feet...; his frock coat hanging; his trousers longer than his legs and tucked up above his ankles; a thick Muslim beard; his clothes slipping all over his body with their legacy of all the accidents he had met on his travels through life... A big flower, fleshy and fresh in his button-hole... and an overflowing, ostentatious greeting in the seventeenth century style..."

O Eco Macaense, May 7, 1932

"In those days, the commonest form transport was the rickshaw, pulled by one coolie and pushed by another. Lara Reis, however, went to his lessons on a bicycle. There were few cars in the city and out of the Lyceu' s teachers it was only Dr. Santas Almas who later on acquired an olive-green Buick which was his pride and joy. However, in the hands of its owner, it hardly proved a rapid way of moving around: Santas Almas' Buick and Father Sarmento's Chevrolet competed to see which could move most slowly through the city streets. The peace of mind of these two men behind the wheel was quite painful to watch. Both Mateus de Lima and Pessanha had their own rickshaws. At around that time, however, Luís Aires da Silva was responsible for bringing in the modern rickshaws from Shanghai with their elegant shape, brilliantly varnished bodywork, and lowslung wheels cushioned with tyres making them easier to pull. Set against these innovations, Pessanha and Mateus de Lima's rickshaws with their high wheels rimmed with thick rubber and cracked varnish would have been better off in a museum than transporting two such respectable people.

Illustration by Carlos Marreiros (fragment)

Illustration by Carlos Marreiros (fragment)

As quicker modes of transport had still not arrived in the city, it was not surprising that teachers often arrived late for their classes and that when they had two lessons in a row they would remain engrossed in conversation, forgetting their pupils completely."

Luis Gonzaga Gomes

(excerpt from original documents in the

Macau Historical Archives)

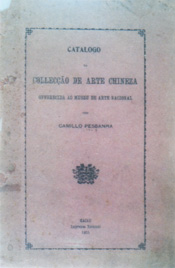

[AOC] "I have known Camilo Pessanha for a long time. He is a true poet and a true dreamer. But he is also timid and a misanthrope. Camilo Pessanha never wrote down any of his poems. He creates them when he feels inspired and keeps them stored in his memory. He only consents to reciting them to his closest friends. Some time ago, after I heard somebody else recite his poems, chopping and changing them mercilessly, I thought it was absolutely essential to publish his best poems in a volume. Then, without telling the poet of my intentions, I asked him to dictate his work as I wanted to keep a note of it. Camilo Pessanha dictated some exquisite poems to me. This was how Clepsidra was born."

[FC] "It's really strange. Both the poet and the public owe you their gratitude. Of course, in the wake of his success, Camilo Pessanha will publish more..."

[AOC] "Of course! Camilo Pessanha is in Macau and there is not a peep from him. Believe you me, he does not hanker in the slightest after fame."

Maria Fernanda

Ana Osório de Castro interviewed by the

writer Fernanda de Castro in Diário de Lisboa,

April 21, 1921

"He always wore the same clothes; as it was summer, a loose, sleeveless shirt which had once been white, and a grubby sheet which covered his legs up to his midriff. He always received his guests in bed, talking with a certain eloquence. He gave off the air of a skeleton which moved as if by magic and in whose eyes, although they had a cast and were different colours, all his energies were concentrated. This was how the great writer Blasco Ibañez found him after requesting Governor Rodrigo Rodrigues to take him to see the poet Camilo Pessanha."

José de Carvalho e Rego

Notícias de Macau, February 11, 1968

"During his long stay in Macau there was not another lawyer who could equal him. His was always the last word, taken and respected as such by colleagues and magistrates even though his indolent, undisciplined lifestyle and not always sociable habits meant that he never had too many clients."

"And while he had a strong grounding in law, once he had demolished his adversary with legal arguments, he had no misgivings whatsoever in turning cruelly on him like a tiger, tearing him to shreds with sarcasm, kicking the life out of him. He did it with such words and in such a way that to avoid being further ridiculed his victim would face him and with a contented, grateful look (as opposed to a hostile frown) would say morituri te salutant."

Silva Mendes

Ideia Nova, nº 13, March 18, 1929

"Pessanha unwrapped the book which he recognised and then opened the letter to read it.

He read it surreptitiously and was going to place it next to the book when, drawing it towards his fiery eyes again, he read the end once more and in a flash of hot temper threw it violently away.

I could not understand that sudden change in temper. I watched his body stiffen and his face become consumed by anger.

These attitudes were not usual: I had already known the poet some years and had noticed that his frequent, violent reactions were more usually expressed through irony or biting comments which while searing, were not accompanied by physical gestures reflecting his emotions."

"Green Hat"

A Voz de Macau, April 18, 1944

"His legal knowledge was extensive and well-served by his exceptional intelligence. This made him the lawyer of many other lawyers who would visit him discreetly in the evenings to ask his advice on even the most unimportant matters.

Confronted with the ignorance of some of his colleagues, his vanity would lead him to comment the following day to his friends:

There was another one round yesterday. But what have these people studied? They don't know anything, not even how to make a simple request, because they don't know how to write.""

He spoke with difficulty, interspersing his sentences with guttural groans which emanated from his cavernous mouth dotted with the remains of teeth blackened by opium smoke.

He laughed at everything and nothing, a satanic laugh. His strange, macabre face made an impression because of the grubby beard and an impertinent squint which meant you could never tell where he was looking...

He questioned everybody's honesty, integrity and competence, particularly his colleagues, with such immense dissatisfaction that he sometimes ran up against trouble and was even attacked by the County Delegate, Dr. Lencastre da Veiga.

He was assured of impunity due to his physical frailness and so his irreverence sometimes reached the stage of insolence, falling over himself with apologies as soon as he saw he was in danger of being punished as he often deserved.

Ngan Yen, "Silver Eagle", Camilo Pessanha's companion(photograph published in Revista de Portugal, November, 1940)

Ngan Yen, "Silver Eagle", Camilo Pessanha's companion(photograph published in Revista de Portugal, November, 1940)

His distraction and total lack of interest in clothing meant that he was almost always ridiculously dressed and it was quite common for him to wear a green sock and a white one.

I knew him for years on end with the same Panama hat which must have been white at some point but had ended up filthy, the same dark amber as his fingers which were stained from cigarettes and opium.

In summer he would receive his closest friends at home without a scrap to cover his body as he lay on a permanently unmade bed with piles of files, rags and dogs which he said were his best friends.

When he smoked opium, which was four or five times a day, he became absorbed, stretched out on his bed like a fasces of bones covered in wrinkled, crusted skin with the appearance of a corpse waiting to be laid out.

He was totally unaware of time and never got to trials, lessons or the Registrar's office on time, nor for any meetings to which he was called.

His watch, which he took everywhere with him, was sometimes unwound for days and days."

Francisco Penajóia

Renascimento, vol. 4, nº 4, October 1944

"Camilo was well known and respected by the Chinese who surrounded him every time he went out into the street. They chattered on to him in the ancient tongue of the Heavenly Kingdom which had, as it became monosyllabic, acquired a further prosodic element: the tones which have no counterpart in any other language. Chinese is imbued with an oratory and poetic value, as I heard from Camilo."

"Before the afternoon set for our visit to his museum, I went in the morning to look for Camilo in his huge old house which was somewhat livened up by fifteen philosophical, leisurely relatives, all of them Chinese. Taken to his room in silence and with ceremony, as a "great friend", I found him curled up on his spartan bed made of steel and wire like a sleepy, dishevelled student. Sleeping like that, with his knees tucked under his chin, he looked like a tiny yellowed wrinkled up wisp of a willow leaf.

A gilded bronze Buddha sat in front of the open window with a slightly smiling ecstatic face and an expression of transcendent serenity.

Two joss sticks burned at the window with an aromatic scent of aloes-wood, the wonderful incense from Angkor Temple and all of that Far Eastern ritual.

Winding its way up the window was a flowering branch of the Chinese aguila-wood.

Two joss sticks burnt slowly in the sunlight in honour of the Earth and dead souls, as Camilo told me later on.

Sam-Khun came into the room with great ceremony wearing blue silk trousers and a silk tunic of the same black as her felt slippers, her black plait heavy with the oil of camelia flowers and bearing a lacquered tray with tea for me and the divine drug for Camilo.

After being softened gently in the flame of some ignited alcohol, Sam-Khun silently, patiently prepared the smoking black ball for the bowl of the traditional long bamboo pipe. The acrid emanations of that other-worldly magic filled the air in the room.

Camilo inhaled deeply and gradually cheered up as if he had been touched by a fairy wand.

He was another man, full of vitality and expansive in his joy. He quickly got dressed and we both went to lunch with my wife in the Hotel Boa Vista where he also dined.

The three of us returned to his home, Camilo still fired with the energy, the physical euphoria, proportioned by that morning's opium."

Father António Maria de Morais Sarmento who was with Camilo Pessanha in his final moments of life and heard his last words, spoken with "astonishing calm": everything is ending... everything rotten... everything material... (photograph lent by Luís Sá Cunha)

"This Camilo was no longer the same as he had been in Macau. Denied his opium, difficult to obtain in Lisbon, Camilo turned to alcohol instead, "et quel démon est plus terrible que l'alcool?"as Baudelaire had once said about Edgar Allan Poe.

My heavy work load in the courts kept me fully occupied and I had no time to go with him at night on his visits during the early hours of the morning to cafes and bars in the city centre, starting his rounds on the square at the end of Rua do Alecrim.

The frenetic stimulation of the cocktails and grogs he imbibed swept him off his feet and he absolutely shone with charm and a critical intellect. People sometimes said that at times his irony could be most penetrating and his sarcastic tongue devilish. Only China could really offer him any serenity and calm for his poor, crucified nerves."

"Camilo left a deep impression on all those who met him or dealt with him personally in the Far East.

He was almost only soul, sweetly ironic and benevolent and completely emaciated. With his large glistening eyes and his long black beard (which had never turned grey), he enjoyed a status of Byzantine mystique in the Portuguese Far East. He was a poetic genius and a major inspiration and one day his work will be inscribed on some solitary rock in Camões' Grotto to lie amongst the lichen, impassive in the life of the city and the delirious fury of the typhoons."

Alberto Osório de Castro

Atlântico, 1942

"In fact, there was something about Verlaine in Camilo Pessanha -- and it was true that he liked to recite the works of the great French poet in the Bohemian literary world: he led a similar life, an unrepentant night owl but more refined for he replaced the beer and absinthe of the Café Procope in Paris with Chinese opium and, when he was in Europe, Scotch."

"Camilo Pessanha was a strange person! Of average height, lean with a greenish complexion framed with his black beard which he claimed was exactly the same as that of Joao de Deus... Partial paralysis of his face had left his right eye immobile and that was the cause of his characteristic squint. At night his glaucous green eyes were like cats' eyes. Feline too was his stance when criticising other poets, including Camões and Antero. Walking along Rua do Arsenal and Rua do Ouro late at night on his way back to the hotel, he would stop to recite his poems which echoed in the silence of the early morning...

Armando Boaventura

O Século Ilustrado, August 2, 1952

"Whenever he came to Lisbon he searched out the cafes which most resembled those huge bars in ports across the world. One day, after watching from a distance the illuminated, tanned Christ-like figure with his hungry eyes and bushy beard, I turned to him and said "You are beautiful!". There was a moment of amazement - my amazement. And then he said"I am the abortion of a great beauty".

Story told by Carlos Amaro

Diário de Lisboa, March 3, 1926

"Henriqueta Pacheco Jorge Barreiros talks of her teacher Camilo Pessanha with a special affection. Now over eighty years old, Henriqueta was sixteen when she was a pupil of the poet.

He was different from all the other teachers. The way he taught made us all feel more at ease.

Pessanha gave his lessons on the same level as his students. It was unusual in those days for teachers to sit with their students and not on the dais. He always had Arminho with him. His little black and white dog was an inseparable companion, even during lessons.

The poet taught anything and everything in his History classes, only occasionally going back to the set programme: We never got any further than Egypt! During the classes Camilo Pessanha would get off the subject and talk of anything: journeys, adventures, books. He could take any historical subject and make it into a completely improvised talk without ever having to turn to books... he had a prodigious memory.

Obviously he was adored by his pupils: We really liked him. We were always surprised when it was time to finish the class. Time went so quickly that when the lesson ended we would always be ready for more... Even though he didn't teach the usual material, he was an excellent teacher.

He was an unusual looking man but his students did not find him unattractive or repulsive: We didn't think he was ugly. He was very thin, he had bags under his eyes and always had a stoop - but he was not ugly."

André Barreiros

Lisbon, March 10, 1990 (unpublished)

"I'm sorry for not having written sooner when you were taking such an interest in my life in your letters to auntie - what has become of Camilo? It is not ingratitude, as you well know, but this sadness which comes over me due to those small miseries, the depressing limitations of life and my own weakness which condemn me to this solitude. It is my own fault that I am drowning helplessly and cannot even reply to the letters my friends send.

Of course you will realise that some letters which I sent as soon as I arrived expressing my satisfaction did not in fact reflect anything other that a momentary desire to delude both myself and others into the comparative well-being that a change of surroundings always brings."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to his cousin José Benedito

Óbidos, August 9, 1893

"My father will have told you of the dreadful state in which I find myself. I left Macau with no hope whatsoever of ever reaching this tower of nostalgia where my soul belongs as well you know. Oh, my aching bones! They are tied to an absurd, invincible destiny of unfriendly exile. How many times have I said that I would wish to end my days in that lovely old house in Marmelos...

Camilo Pessanha's grave where he is buried with his son and daughter-in-law in the cemetery of São Miguel Arcanjo in Macau

The desire to come back to the things and people I love has never been so strong as when a doctor I trust told me that I would never be strong enough to undertake the voyage home. Now I tremble with a desperate energy which forced me to get up from the bed in which I had been imprisoned for the last five months and made me board ship; and I tremble too from my poor, sickly body's resistance which was capable of suffering the forty days of this sorry voyage with no doctor, no treatment, no special diet, no nurse or even a friend to take care of me..."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to his cousin José Benedito, 1905

"What strength I have found since being in Portugal for five or six days! I feel life surging up from the ground into my feet. If I were to stop walking around, I would surely turn into an old oak tree.

Tomorrow I will be in Lisbon to sort out the licence from the council and then I will go to Arelho to watch the waves battering against the stones. And then I will go to Mouronho to cut wood, and on to Lamego, São Pedro de Val Do Conde and then travel to fairs and pilgrimages with gypsies and smugglers and assassins..."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Osório de Castro, 1896

"I am only writing to you today because I have not written to anybody since embarking. It's that malaise into which I fall for long stretches at a time yet which allows me to work on cases, read books and study Chinese. Do anything, in fact, which can distract my attention and tire my spirit and which can inhibit me entirely from looking into myself for a single moment and writing a letter.

I arrived on May 21st, and I'm getting along a little better. At least I have my days almost filled and I pass my free time by reading. While there [Portugal] I couldn't even do that: I was living in a state of convulsive exaltation which prevented me from getting enough rest to be able to read two lines in a row. Even while I was on board. Can you believe that I spent the entire fifty days of the voyage languishing in a chair unable to read even Ruben Dario whose work I had bought in Barcelona?"

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Alberto Osório de Castro, 1918

"P. S. - Do you know what I most wish for now? Never to arrive where I'm going... to travel for ever on a ship going nowhere.

Imagine how fate can change. During my last days in Lisbon, I felt truly oppressed by the fear of the dead sea of the voyage between two abysses, each so far from the other, and for which my soul is in constant anguish."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Carlos Amaro, January 1909

"Farewell, The monotonous life on board ship is stupefying, brutalising. What's more, today there was some rocking which left me with a headache and my stomach feeling most upset. The worst thing is the latent pain which lies at the base of that torpor. People suffering paralysis must feel a constant, numbing pain like this..."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Carlos Amaro, February 1909

"Farewell, my dear friend. I send you from Macau the constant numbing pain of my soul, an ache which is almost asleep while my eyes flicker during the day from sight to sight but which takes its revenge at night (in nights of ghastly heat from Singapore) in the most dreadful nightmares. I wake up shouting, aching and exhausted with my head soaked in perspiration. The night before last I dreamt that I was arguing with my brother Francisco, or at times my brother Manuel and that my arms were pinned. Pinned arms, the constant fear in all my nightmares..."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Carlos Amaro, February 1909

"I can truly say that inside my heart I carry an altar with three or four icons and that I spend my life in front of it in uninterrupted ecstasy. Other than these few distractions (one of them as you know is the frightful anguish of my soul) there is nothing which is truly authentic for me in this world through which I have passed like a sleep walker."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Ana Castro Osório, November 1906

Father Sarmento, described by Henrique Senna Fernandes as "one of the most characteristic figures in Macau in his day" (photograph lent by Luís Sá Cunha)

"I went myself to the Post Office to register everything with a receipt in view of the news carried by the papers that the seas in the West are far from safe. On my return home I lay down as usual to take stock of a job well done. Naturally, while Silver Eagle (I will soon be sending Trindade Coelho a picture of the poor little thing [his concubine]) was preparing and serving my comforting drug, I gradually began to enter into that lucid delirium so characteristic of hypnosis. If you can forget where you are, you can recreate entirely different situation in another place or another time as if you were living two lives at the same time, each at a great distance from the other. My imagination took me far off td the sterile agitation of life in Lisbon, the vain, aggressive tumult of life where I wandered despondent and down-trodden for five awful months. In the background was a succession of delirious figures whom I knew in better times: Braga from the play, his eyes demented, Américo de Oliveira, Rocha the cork dealer, Burnay the caricaturist, the poet Antunes Belo and so on and so on..."

Camilo Pessanha

Letter to Henrique Trindade Coelho

November 1916

Illustration by Victor Hugo Marreiros (mixed media)

*Whenever he met one of those undesirables in the street, it was said that he gave them a special greeting by reverently doffing his hat and placing it over his heart meaning that he was sending them to hell.

start p. 11

end p.