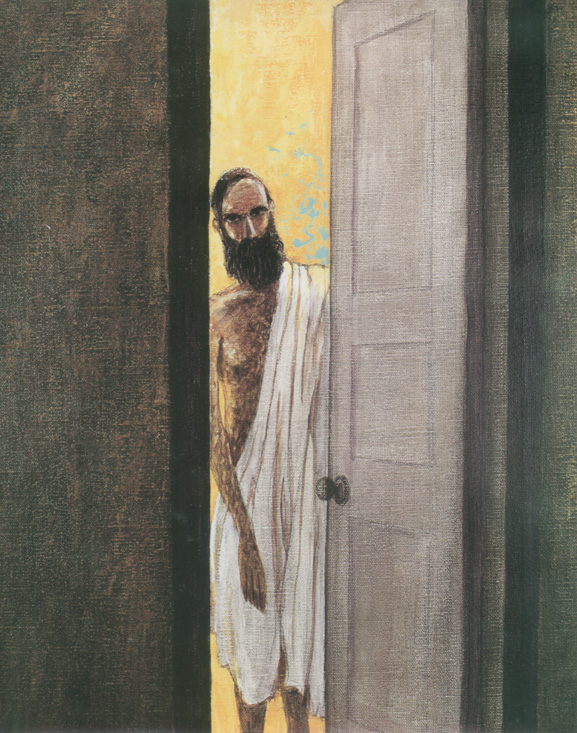

Painting by Nuno Barreto (acrylics on canvas,46cm×38cm)

Painting by Nuno Barreto (acrylics on canvas,46cm×38cm)

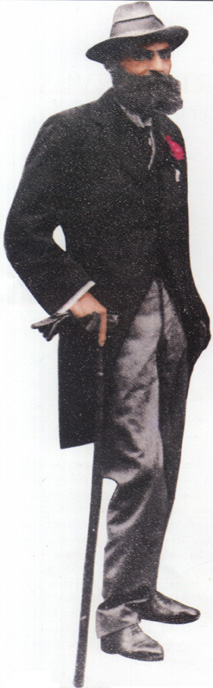

Pessanha's personal seal

Pessanha's personal seal

"PESSANHA in shirt sleeves" points the way towards an introduction into the private world of Camilo Pessanha. It is an attempt to draw back the curtains veiling the purity of Camilo the man to reveal his physique, psychology, his traits of character and the circumstances in which he lived. This is a glimpse of a man through a door which has been pushed ajar. Eye-witness accounts are provided by those individuals who observed Camilo in his semi-naked state, the bony sculpture of a fakir, a living corpse shrouded in a sheet as he used to lounge in the inner precincts of his home on Praia Grande.

It is man's tendency to shroud himself in veils, in cocoons. These makeshift garments envelop him in a budding mystery. Clothing and homes together obscure the individual and as such can take on a genuinely ontological dimension. They protect and establish barriers against the world, that shared space in which we all play out our lives. By removing his clothing, we reduce the individual to his most basic self. By peeling off layers of clothing, man can reconquer states preceding his own Being. Thus the initiate conceals himself by rebuilding his own paradise or by recreating an artificial paradise.

It is licit only for each individual to undress himself. Cruelty, in its avarice, invades solitude and reveals secrets in order to expose that which has been imposed and to degrade that which is out of the ordinary.

As Madame Cornuel noted sharply, "no man is a hero to his valet" and there are indeed many aspiring valets. Advocates all of them, the Devil is nothing but a voyeur.

Our justification lies simply in the fact that our motives in bringing so many diverse scraps to light are not diabolical but rather intended to build up a portrait of Camilo the private man. There is, of course, no sense in putting a private life under the microscope if there is no intention of explaining the mystery of artistic creation through psychoanalysis. Frequently, the path of detailed discovery is an exercise in finding the lowest common denominator.

On the contrary, we have omitted those comments which most obviously reveal signs of envy (such as the person who dared to say of Pessanha that "he is not a poet in the true sense of the word"), in the knowledge that by printing them we would be lowering ourselves to the same level.

The following excerpts are simply an attempt to provide the reader with a full length portrait of Camilo Pessanha, a picture of the reclusive somnambulist at home in his bedroom. By doing so, perhaps we will be able to reconstruct the personality of a man who held onto his private life with the most extreme tenacity.

The source of most of the excerpts is a collection of personal accounts compiled and edited by Dr. Daniel Pires in his book Homenagem a Camilo Pessanha (IPOR/ICM, 1990). Where necessary, explanatory notes have been added. There are also some letters written by Camilo Pessanha himself. Illustrations have been provided by Nuno Barreto, Carlos Marreiros and Victor Hugo Marreiros.

The material should open up paths for new research into the relationship between biographical fact and poetic creation, highlighting the Aristotelian claim that Poetry is greater than History in that it transcends the constraints, pains and corruptibility of daily life.

Particularly relevant to this concept is António Quadros' introduction to his study of the poet's works, Obras de Camilo Pessanha, Clepsidra e Poemas Dispersos (Europa-América, 1988):

What man does is what he is and what a man is can only be attained through what he does. Poetry is essentially a creative process - poiesis -- a magical process of a greater being, an artistic being, the alchemy of rhythm, song and the word. Through this poiesis the poet creates himself or recreates himself as he was in the beginning. In his poetry he seeks to find his essence in the fluid existence which consists of an unstoppable future and constant corruption. It is as if each poem were the receptacle in which something of his own substance can be held, that which is most genuine, most profound, most imperceptible, something which in the implacable finality of time would be forever lost.

Thus a poetic work is a kind of double evolution of the poet: it is there to stay for ever. A poem can be a conscious release or a subconscious confession, exorcism or aspiration, sincere or feigned. It can be the vision of something unspeakable which can only be alluded to through metaphor or symbols or it can be the expression of a tragic inner discord. However, a corpus of poetry which brings together the axial moments of a writer's dispersed existence is reduced to its essence in the effort and liberation of poetic composition. It builds up a picture of the writer which is more accurate than that which others may have seen on a day-to-day basis and possibly more accurate than that which he himself saw in the blurred mirror of introspection. Poetry communicates on more than one level, there are layers of meaning which lead beyond the meaning of the words themselves.

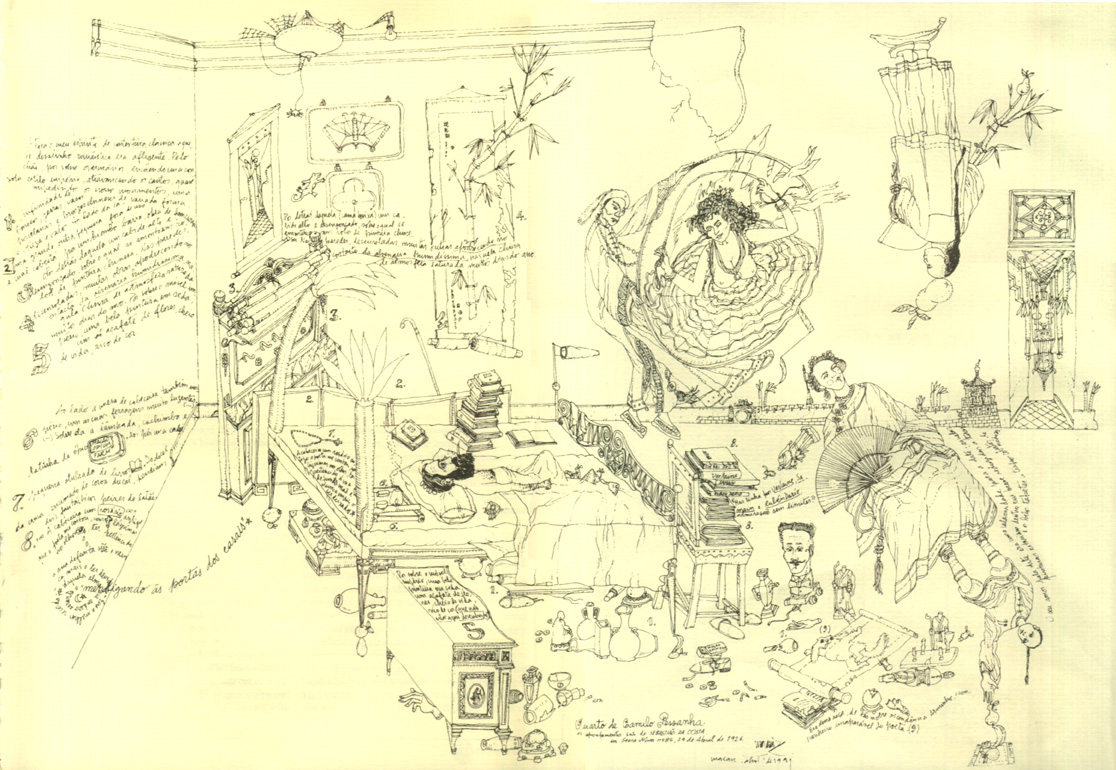

THE articles about Pessanha include a second section dealing with his house in an attempt to rebuild it based on the scanty literary documents and urban records which have survived. There is also an article on where number 75, Praia Grande actually stood and what it might have looked like.

A different slant is provided in the article which explores the profound relationship between the man and the house, the nearest thing we have to a microcosm, a universe which is organised (or disorganised) by man's spirit. This is what Gaston Bachelard meant when he talked of the house and its rooms as being written by great poets and writers. Thus they serve as tools for analysing the inner life of the individual.

By reading Camilo Pessanha's house, we discover a search for and the protection of privacy, the frontier separating the outside world and its need for objective reality from the inner sanctuary.

By entering Camilo's house, we take by surprise the bastion of privacy in the ultimate shelter of his bedroom. The labyrinths of chaotic antiques lead like ramparts, decoys and defensive infantry protecting this solipsistic sanctum.

The poet usually only allowed his dogs into his bedroom, particularly Arminho. By the window sat another pet: his parrot, the irrational messenger communicating with the outside world (or perhaps echoing the voices and shadows inside), an outside world full of scenes which filled the casements of his bedroom window.

In a comer of the room stood the central fortification of his shelter, the sanctum sanctorum of his hallucinatory vigils and long trials: his bedstead with its iron bars where he would lie in the foetal position, his knees drawn up to his chin, his lanky body scarcely discernible under the cornucopia of sheets.

There, in his house within a house, he lay like a mollusc in the security of its shell, retreating from lukewarm maternal limbs into dissolution in the vast seas of the subconscious. ("Sleep. Do not breathe. Do not breathe.")

Pessanha's room seems to suggest a death chamber, reflected in the silence of his pleading: "Oh, death come quickly/ Awaken, come quickly/Relieve me quickly".

Camilo Pessanha comes to mind as a poet and soul caught in the extremities of decadence, lost in a lost country in search of exile and freedom. This a man who, in his letter to Carlos Amaro, expressed his desire to Never to arrive where I'm going... to travel for ever on a ship going nowhere. This is the poet who hoped to slip away "like dying water" because he felt that For the best, in the end, Is neither to hear nor to see... For them to pass over me and to feel no pain!... And I on terra firma, compact, trodden, Terribly quiet. Laughing because nothing pains me.

Pessanha took refuge in lethargy as a result of his desire for solitude. He combined the crepuscular character of the Portuguese with the crepuscular weight of the symbolist and the anguished sensibilities of fin-de-siècle decadence.

With no world, lost in a lost country, Camilo turned in exile to the pathetic consolation of the opium addict, his solipsistic imagination making its way through an improvised illusion of a world. He became engulfed in dreams and soporific stupors as children do when they hope to escape from the objective realities of the world.

Camilo and his house: his house within a house where he could take refuge from his incessant search for finality. A strong-house but lacking the thick, rigid walls, a house which combined and almost merged with his personal identity. After the mother-house which conceals us, envelops, absorbs and accompanies us always, the mollusc's shell comes as a natural progression for it can cover the vulnerable softness of the living body.

It is unfortunate that Camilo Pessanha's house was completely demolished a few years after he himself passed away for this was surely a point in the city marked by a truly intense, dynamic experience.

This was the house where the poet kept his concubine closeted in absolute privacy in a complex relationship with the protectress and creator of his own world. She was the maiden who would always gather up his deathlike carcass in linen sheets.

Camilo and his bed. The cradle of his evasion, his hallucinatory voyages, his hoped-for dissolution. There, at least, he must have discerned that to die is merely to be born backwards.

RC POSTER

Drawing by Carlos Marreiros "Camilo Pessanha's bedroom" (China ink on cartridge paper, 68cm×42cm)

start p. 5

end p.