THE PORTUGUESE VOYAGES-ORIGIN OF THE FIRST DIRECT CONTACT BETWEEN EAST AND WEST

The misty Orient, with its "hidden new people, never before seen", had, in the colourful words of Diogo Velho, become a reality: "everything has now been discovered, what was distant is now within reach, future generations will certainly attain the treasures of the Earth" (1).Not only did Vasco da Gama's journey open a new trade route for commerce from the Orient to the West, it also caused the Arab and Italian traders to go bankrupt. At the same time it was the last step in the attempt to tame the "Terrible Ocean" first undertaken by Prince Henry the Navigator. For two centuries cartography, cosmography and navigational techniques had been developed and improved. There is evidence of this in the Portugaliae Monumenta Cartografica and in the geographical and cartographical notes made by the Portuguese travellers on the most remote corners of the Earth, until then unknown to Europe. There is other documentary evidence such as the letters written by the Portuguese Missionaries, Álvaro Velho's diary of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama, both diaries from da Gama's second voyage (one written by Tomé Lopes, the other anonymous), Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis by Duarte Pacheco Pereira, Summa Oriental by Tomé Pires, Peregrinação by Fernão Mendes Pinto, Pêro Lopes de Sousa's diaries, Duarte Barbosa and Francisco Rodrigues' writings, the anonymous Livro de Rotear, the anonymous diaries of Pedro Álvares Cabral's voyage to Brazil and India, João Lisboa's Livro da Marinharia, Arte de Marear by Francisco Faleiro, Dom João Castro's Roteiros, Tratado da Sphaera and Cartas, Bento de Góis' notes, Padre António Andrade's Novo Descobrimento do Grão-Cataio dos Reinos de Tibete and his travel notes.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN THE ORIENT

As a result of their scientific voyages to India in search of the Christian Monarchs, Portugal brought pepper for the kitchen gardens. More importantly, driven by faith and heroism, Portugal awakened a petty, greedy southern Europe to a concept of the world as a stage on which history could be enacted. Geographically, Portugal constitutes a small strip of territory on the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula. Even at the height of its expansion it could never have attained the size of population needed to conquer and control the expansive area with which it had come into contact, defined as the 'Mundo Português' in the Treaty of Tordesilhas. At large in vast areas, limited only by the sea and the sky, the Portuguese sought and promoted friendly relations with the people with whom they came into contact and, in general, respected the various ethnic differences. This formed the basis for the exchange between Portugal and the Tropics. The effects of this are seen in the Portuguese mentality. At the same time, they created small replicas of their own social structure: wherever they went they built humanitarian institutions for the benefit of all those who sought relief from distress regardless of religious or racial differences. In the Orient their settlements and fortresses were based around the parish church with its school, the Royal hospital, the Santa Casa da Misericórdia and, occasionally, an orphanage and a hospital for the poor. These humanitarian establishments were funded by donations from the Knights of the Order of Christ (who had always had connections with the Church) and by the profits from the very same settlements which apportioned money to these physical and spiritual ministerings, whether religious or lay, in the name of God and the King. Their activities, based on a concept of the brotherhood of man (2), were in blatant contrast to the other "Christian" European nations which built odious, economic empires in the Orient in the name of Christianity and racial superiority.

CONSEQUENCES OF THE PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN THE ORIENT

What were the consequences endured by the ancient civilizations of the East and, in particular, the coastal areas, due to the arrival of European vessels? The first major European influence, and the most positive, is evident in the title which several kings of the East who were in contact with the Portuguese Crown bestowed upon themselves: 'Brother of the King of Portugal'. This is evident in the following passage:

"at that time I had no assistance other than that of the gods by whose grace and benevolence I had a small Portuguese fleet commanded by my lord and brother Duarte Pacheco Pereira, a noble of the Portuguese Court...". (3)

1 - Tapestry in Portuguese and Indian style. Detail of one of the "news" tapestries ordered by Dom Manuel I to commemorate the arrival of the Portuguese in India which illustrated the meeting of East and West and reflected the impact of and the fascination with the exotic in Europe.

1 - Tapestry in Portuguese and Indian style. Detail of one of the "news" tapestries ordered by Dom Manuel I to commemorate the arrival of the Portuguese in India which illustrated the meeting of East and West and reflected the impact of and the fascination with the exotic in Europe.

It is interesting to note that this fraternal attitude was established by the King of Portugal in his first dealings with the kings of the Orient:

"Great and powerful Prince Zamorin, King of Calicut by the mercy of God; we, Dom Manuel, by the grace of God King of Portugal and the Algarve, Lord of the African seas and Guinea, convey our greatest respects to the one whom we so much love and admire... and our wish to talk with you and cooperate with you in the spirit of brotherliness and love which befits Christian kings...". (4)

This message, delivered by Pedro Álvares Cabral, formed a basis for economic and political relations between different countries, marking the start of international law. It also demonstrates that the kings of India and of the Orient were not against the establishment of settlements by the European navigators nor their religion so long as they did not have recourse to violence. This condition was set by Zamorin, a Hindu prince who already knew the Christians of São Tomé on the Coromandel coast. Chrisian missions in the East, when peaceful, were extremely successful as is demonstrated by the method adopted initially by the Brothers of Saint Augustin.(5) Benefitting from their knowledge and culture they first converted members of the oriental royal families and the aristocracies such as: Prince Dom Afonso Nordim and Dona Filipa, the children of the bailiff of Ormuz; Dom Jerónimo Joete, son of King Turumsha of Ormuz and heir to the throne; his sister, Dona Margarida, and his nephew, Dom Filipe; the queen of Kurdistan, Guativanda Dedopoli; the king of Pemba, Dom Felipe; the prince of Melinde, Dom Antonio Clingoliat; Dom Aleixo de Meneses "a high-ranking descendant of the Great Mogul" and his brothers Dom Carlos and Dom Filipe; Dom Martinho, Prince of Arracão, son of the Mogul king and Nicolau Rebelo his cousin; Dom António do Rosário; Dona Mónica de Graça, daughter of the High Treasurer of Macassar etc., etc. (6).

Many of these Oriental Christians led exemplary lives when their conversion was due to sincere conviction and not economic and political pressures, for instance Dom Manuel and Dom João da Cruz, relatives of the monarchs of Cochin and Calicut who were baptized in the Portuguese Court (7). Some of these converts devoted themselves, in turn, to the Conversion of the East. Included in this category were Dom João da Cruz, Dom António, Prince of Bosnia, Gaspar da Graça's brother, Father Tóme da Madre de Deus, Father Agostinho da Conceição from Cochin "the greatest theologian of his day, so great that even today he is still referred to only as Father Agostinho the master. He was a man of virtue, his life was exemplary... he held positions of the greatest authority in the Church... The Jesuit, Father Cipriano, imprisoned by the Inquisition after driving the best theologians of Goa to their wits' end, was turned over to Father Agostinho the Master who came out victorious having left the heretic convinced of the superiority of Catholicism over his own dogma" (8).

This leads us on to the documentation of the conflicts between the religious orders, who, under the cover of Christian virtues, but at times forgetful of them, caused civil disorder and shameful mass baptisms. This was, quite obviously, against the evangelical tradition, and was motivated by an anxiety to attract the substantial donations which the King of Portugal, as Patron of the Orient, made to the Church and the religious institutions (9). Completely abusing their position, they claimed all kinds of pernicious privileges from Portugal and the Orient, taking advantage of the "jurisdictional immunity" of the archdiocese of Goa, the viceroys of India and the Portuguese monarchs. This is proved by the theft of Goa's revenue and the constant protests of the viceroys, governors and archbishops of Goa. Even the P pe expressed concern:

"The Pope is happy to know that Your Excellency wishes this to become part of his holy see. There are great works to be done in those parts, not for the ambition nor desire for honour which many brothers have". (10)

The missionaries made excellent innovations in the cultural exchange between Portugal and the Orient, cultures which seemed to have nothing in common. They were pioneers in exploiting the cultural traditions of old India, thus establishing a base for cultural adaptation and the Indianization of Christianity. Roberto de Nobili is a good example of this. He went to a meeting of the castes and became a "Sansayi Brahman", living with Hindu priests in the "ashrams" with whom he discussed the Veda while preaching the word of God. Father Tomás Estevão published a remarkable Indianized version of the Gospels, the Xtrista Purana, which is still of great interest today. Dom Francisco de Garcia, the bishop of Cranganor was the greatest defender of the Indianization of the Christian faith and contributed much to this aim. He freely used Hindu philosophy and folklore in his missionary work because he realized that in essence Hindu philosophy was not only profound but also that its basis was not fundamentally different from that of Christian ideals. Not understood in their time, this tiny minority group of Portuguese missionaries living four hundred years ago, was in fact, the precursor of the modern Catholic Church's ideology proclaimed in Vatican II.

Portugal did not restrict itself only to missionary work and establishing social contacts. Portugal was also involved in educational, scientific, linguistic, cultural, artistic and humanitarian activities. Portugal's humanitarian work in the East was not only the first, it was also one of the greatest feats in the history of mankind. Although dispersed and fragmentary, documentation shows that Portugal created the Santa Casa da Misericórdia for the "service of God and the King", putting into practice the ideal of fraternal love and devoting time, effort and money with no motive other than charity:

"This Portuguese company is called the Misericórdia". These good men have paid wonderful tribute to God, our Saviour by helping the needy".(11)

The proliferation of the schools in the Orient was another example of the Portuguese influence. Afonso de Albuquerque's small parish school in Cochin (12) expanded over all the Portuguese settlements and, as early as 1541, there was a seminary in Goa for "young men from Malay, Malacca, China, Bengal, Siam, Gujerat, Mozambique, São Lourenço and many other nations who could benefit from an education" (13), funded by the King of Portugal who donated a substantial amount from the revenue of Goa "to sustain those who are now studying and those who will study in the future" (14).

The regulations of the College of Saint Paul ordered that there should be "a grammar master in charge of all the students who must learn and study well their subject as with the teachers of the other sciences, arts, logic, philosophy and theology..." (15). Music was one of the most important disciplines in the domain of the arts (16). Several of the students were "already good grammarians and whatever they may be taught they study with great diligence and love" (17). Several Jesuits complained in their letters of the lack of a good library and good teachers:

"... they have the will but no masters to teach them well, to teach them to speak Latin nor to make them memorize except the Rules of Anthony and then only in a confusing way". (18)

Yet, this was generally believed to be one of the best Jesuit colleges in the world and was the most outstanding example of Portuguese schools in the East (19). It was through this institution that printing techniques were introduced to the Orient.

Another positive influence was that Portuguese was the "lingua franca" of the East for almost three centuries (20). The linguistic developments from this were interesting. Some Portuguese words were introduced into Oriental languages and, conversely, many oriental words were introduced to European languages through Portuguese, such as sandalwood, nawab, satin, zamorin, mandarin, lascar, balloon, bamboo, jaggery, curry, copra, betel, sago, sepoy, cha, chintz, cashmere, bengaline, kabaya, cambric, etc. The "cartaz" (trading charter) and the "feitoria" (trading settlement) gave excellent support to the commercial transactions in the Orient. Several other Portuguese words were imported into the Orient after some phonetic adjustments. Monsignor Dalgado cites the following examples: "armário" (cupboard), "biscoito" (biscuit), "câmara" (town-hall), "cadeira" (chair), "chave" (key), "couve" (cabbage), "gentio" (heathen), "grade" (railing), "hospital" (hospital), "música" (music), "provisão" (supplies), "provimento" (provisioning), etc. The meaning of some of these words was altered to a greater or lesser degree during these linguistic transactions. For example, the Mandovi, which is the name of the river which flows through the cities of Goa and Panjim was altered in meaning by the Portuguese as is demonstrated in the following document:

"... we presented Governor Dom João Castro with the accounts and he has seen fit to exempt our regiment from the payment of the tax of the Mandovim which is the customshouse...". (21)

"Of all the European nations to traverse the seas in search of the fabulous Orient, only Portugal displayed a more lasting interest than the simple, highly profitable economic exploitation, achieved through military superiority, which was carried out by most of the European countries in Asia... In contrast to this, Portugal's influence was felt in a wide variety of human activitieslegal, social, religious, political, linguistic, artistic, scientific, cultural, humanitarian among the most important; activities which no other country repeated in Asia".

"Pagoda" ("da-goba"), the oriental word for a temple or idol, became the word for a golden coin used in the State of India. Although this word has been imported by other European languages, it is only in Portuguese that "pagoda" has acquired an additional connotation. Now it is used to mean merrymaking and festivities but originally it was synonymous with destruction. This was probably due to the destruction of the pagodas on the Island of Goa during the reign of Dom João III.

The words "pag" (salary, payment) and "pagar" (to pay, but used as a noun) were adopted into Indian as "pag", "pagar" and "pagari", the latter synonymous with stipend (22). "Pagari" is widely used in several Indian languages to describe a bribe in a rent, business or real estate contract. This "pagari" is probably a derivation of the Portuguese word even though its meaning has departed from the original.

The word "caste", from India, has been adopted by many languages both in the East and in the West. However, this word has developed a connotation of rigid social divisions which never existed in the language of origin. Nowadays it means the whole area of socio-political discrimination.

"Rendiero" (rent collector), from the word "renda" (rent) was absorbed into Konkani (an Indian language) to mean "a subcaste of Sudras who live in rented accommodation and rent out palm trees for making fermented palm juice" (23)".

"Burro" (donkey) was used for a short period of time in several Indian languages but now it is only used in Konkani and Singalese and only in its figurative sense.

As well as striving for better geographical and cartographical understanding, Portugal contributed to the fields of medicine, agriculture, zoology and botany. The Portuguese carried out comparative studies on oriental and occidental medicine which were of immense scientific value. Garcia da Orta was at the forefront of the field. Even today his work Os Coloquios dos Simples e as Drogas e Cousas Medicinais da India, published in 1563, is a rich source of scientific information.(24) The Portuguese also introduced certain medicines into the Orient such as quinine (Chinchona Officinalis) from Peru, introduced in 1676, and Herba Malabarica (Holarrhena Antidysenterica) from India, introduced in 1563.(25) Both of these drugs were already being used by the Portuguese for treating dysentery (26). Thus the Portuguese not only brought medicinal knowledge from other parts of the world, they also studied the properties of plants native to India with an aim to finding an effective treatment for local ailments which were often fatal due to a lack of available remedies.

The Portuguese also studied the wildlife in the East. They took specimens of several unknown species back to Europe (27) and effected exchanges of species between the Orient and the most far flung corners of the "Mundo Português", thus enriching the fauna of the East.

The "flora of Asia and, in particular, of India has Portugal to thank for the introduction of many plants which came originally from America. Many of them grow spontaneously covering large areas of ground and are of great use" (28). Among those ornamental plants which Portugal took to the Orient were the Jacaranda Mimosifolia and the Peltophorum Ferrugineum Acutifolia from Brasil (29) and the Plumelia Acutifolia (red jasmine). The latter was to become one of the most popular trees in the East, believed by the Buddhists of Sri Lanka to be the Tree of Life. At the turn of the 17th century this tree also held a significant place in the cultural life of Portugal and was used as a metaphor for the night jasmine in the oriental poetry of Rodrigues Lobo (30).

The various other plants which were introduced or popularized by the Portuguese influenced the economy and the eating habits of the Orient. The pineapple was taken from Brasil to India in 1548 (31), The papaya was taken from South America some time before 1656 (32). The guava was taken, probably from Brasil, at the beginning of the 17th century (33). The potato was introduced some time before 1615 (34). It is not known when exactly the Portuguese took the tomato from Brasil (35). By 1570, capsicum was being cultivated in Goa (36). In Goa it was given various names: a fresh pepper was described as "green" and there was also the "button" pepper, the "dry" pepper and the "round" pepper. These derivations were possibly due to the attempts to cultivate the pepper in the East to substitute or to complement the black pepper. Although corn is mentioned in the Veda it was the Portuguese who brought it into common use in the East (37). The same was true of the cabbage. There were already several kinds of oriental cabbages but, as is reflected by the use of the word "kobi" in many Indian languages (the Portuguese for "cabbage" is "couve"), its increased use was influenced by the Portuguese. The Portuguese may have been responsible for taking the peanut from Brasil to the East. The cashew was certainly introduced by them over four centuries ago, making India the largest producer and exporter of this nut and its derivatives, now commanding 90% of the world market (38). The mango, "queen of fruits", was perfected thanks to the Portuguese who introduced the technique of grafting to Goa thus allowing a greater variety and quality of produce (39). Even now, in horticultural competitions, the mangoes from Goa are invariably deemed to be the best in the Indian subcontinent. Here is an interesting text which reflects Portugal's desire to spread agricultural knowledge (40):

"My friend, the Governor of the State of India. I, the King, send you my highest regards. I have charged Father João de Brito, who is at present passing through your State, and the Church representative in the Province of Malabar with seeking out men practised in growing cinnamon and black pepper to be taken to Bahia to cultivate them there. I ask you to assist them with the necessary expenses and request that you send the men on the first boat which leaves for Bahia where they will come under the responsibility of the relevant governor who has already been given orders. Lisbon, the 10th of March, 1609. The King."

It is evident that no other country took such an extensive interest in the environment as did Portugal.

Artistic exchange was also an important aspect of the relations between Portugal and the Orient. Indo-Portuguese art is considered to be the most beautiful example of this. The establishment of the "Casa dos Vinte e Quatro" (The Chamber of Twenty Four), with legislative powers and participation in the Senate of Goa (41), was the basis for a complex process of cultural osmosis. This development has still not been fully examined, although several specific studies have been done which reflect an extremely rich artistic heritage (42). The Portuguese took new techniques which were adopted by the artists and craftsmen of the Orient, particularly in India. The mixture of the highly stylized traditional techniques with the new ones brought by the Portuguese produced new artistic styles which reflect a permanent tension between the old and the new. These factors combined perfectly in an irreversible cultural symbiosis which escapes all preconceptions about artistic categories. Sculpture, statues, religious art, music, furnishings, tapestries, embroideries, goldsmithery and painting are the best examples of Indo-Portuguese art.

The detrimental effects of the Inquisition and the Provincial Councils in Indo-Portuguese art cannot be denied. According to the Rev. Prof. Dr. Silva Rego this was in line with the mentality of the day which deemed that "he who ruled ordained the religion"; the case in Europe as much as in Africa and Asia (43).

The Portuguese found in the Orient peoples who still adhered to their ancient civilizations although they were already in decline. This is particularly true of the status of women, the standard by which any age, civilization or society can be judged. The influence of Hinduism covered all of the Orient and at its height, especially in the Vedic period, the status of women was raised to the privileged position of intermediary between the gods and men. No religious or social function could begin without their beneficial presence. However, when the Portuguese arrived they found the position of oriental women to be one of abject degradation where they were nothing more than scraps of human flesh to be thrown onto a funeral pyre or herded together for ritualistic prostitution in some of the temples which had, in other times, honoured them.

2 - Indo-Portuguese table - ebony inlaid with ivory.

Among the first laws to be drawn up in India was a ban on suttee, ordered by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510 because the burning of "innocent lives" was contrary to "Moral Justice" (44). Respect for women was further attained through later laws such as making their social situation legal, providing them with economic assistance and legalizing their right to inherit (45). This process was promoted to a great extent by Viceroy Dom Constantino de Bragança who, through the Church and the Inquisition, consolidated his right to impose equality between men and women according to God's law and the law of men. He strove to establish legal, social and religious infrastructures which would attract women to Christianity, at times coming into conflict with other socio-religious groups of the State of India which condoned the degradation of women.

THE ATTRACTION OF MONEY

The defeat at Alcaçar-Quibir and the disappearance of the old Portuguese aristocracy affected all of the colonies and shaped a new path for them. While Brasil became the last stronghold in defence of Portuguese nationality, the State of India, which stretched from the Cape of Good Hope in Africa along the seas, trading settlements and fortresses on the coasts of Asia to Nanking in China believed itself to have been left to its own devices with no fleet to defend them from attacks by the Spanish, English, Dutch, or French, who in their hurry to establish commercial companies for the economic exploitation of the Orient, had frequent recourse to spying, piracy and even the abuse of religion so as to carve out vast colonial empires in the areas that already came under Portuguese control. For example, the "route" used by the French Apostolic Vicars in the Orient was very interesting. Also, the Portuguese ships "S. Filipe" and "Madre de Deus" which were captured by English pirates had on board not only fabulous treasures from the Orient but also extensive documentation of the trade between Portugal and the East. With Elizabeth II's approval, this information was used to establish the "Company of Merchants of London Trading to the East Indies" in 1600, which later became the "London East India Company" (46).

Portugal believed that support for their independence in the East would come from the Pontiffs of Rome. This loyal nation at its peak had always used a portion of the magnificent profits gained from trading with the East for missionary work in that area because, at that time, "the Popes had their hands full with the business of Rome and the rest of Europe and could not consider converting heathens due to lack of money. They had nothing. The action of the Portuguese Monarchs was almost a favour" (47). Yet Rome, forgetful of its moral authority, played politics. Portugal's problems began when Rome refused over a long period of time to recognize Portugal's independence from Spain. This attitude was the "principal cause of the rapid decay of Portugal's missionary work" (48). Another political problem was that Rome handed over some of the Portuguese territories in the Orient to the "Loyal Doctrine" and to its "Apostolic Vicars". Rome bent under pressure from haughty, imperial France and Spain who were fearful of issuing laws contrary to the papal edicts. After the restoration of the Portuguese monarchy, the Spanish crown was strongly opposed to the Portuguese colonies. This was particularly obvious in their attitude towards the sending of missionaries to the Orient. They were opposed to the appointment of missionaries from the Portuguese colonies who were often not even Portuguese (49), showing complete disregard for the "Apostolic Bishops and Vicars" who were appointed by Rome.

Forced into a situation which it did not wish, Portugal had to fight not only against the mercenaries who came from Europe to seize part of the commerce between Portugal and the East, but also against the political and religious encroachments being made by the other European nations with the support, more or less overt, of Rome. Consequently, chaos was thrust upon the Orient as a result of problems originating in Europe.

The position of the State of India became untenable due to the wide area of land it encompassed. Small areas of spontaneous resistance developed. Thus, at this critical point, the intervention of the Hindus from Goa in several of the Indian courts was very significant. They carried out tactfully all the missions with which they had been trusted, financing with money of their own the expenses which were not funded by State (50). Sometimes it was actually the oriental princes who defended the long established friendship between the Orient and Portugal. For example, in 1620 the Prince of Tanjor, Ragunath Nayque, sick of Dutch and English piracy, signed a peace and trade treaty with the Danes on the condition that there be friendship between his state, Denmark and Portugal (51). It is interesting to note that one of the many attacks that Goa suffered was in 1641 when the Dutch invaded Goa from the sea and Prince Adil Can Adilshah surrounded the city on land. When Prince Adil Can Adilshah found out that the Portuguese monarchy had been restored he retreated immediately, saying that he was a friend of the King of Portugal while the Dutch continued their attack until being defeated (52). The resistance in the East gradually fell away, however, due to the strength of the mercenaries. There are two more examples of this resistance worth mentioning. One of them, Solor and Timor, is still in existence. Its resistance was carried out very shrewdly. The other was in Siam where the local reaction to several kinds of intervention by various European countries produced unexpected results.

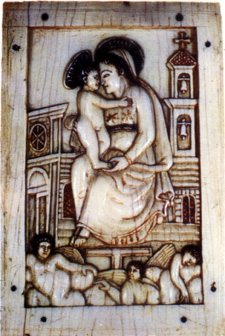

3 - The Virgin with the Holy Infant - bas-relief on an ivory plaque (Indo-Portuguese art.)

The first mention of Solor is included in news on a large area of Indonesia. At first a group of islands was called Solor but then the name was used for only the one island. Timor is first documented by the Portuguese in a letter from Rui de Brito Patalim to Dom Manuel, written in 1514 (53). The first descriptions of Solor and Timor are to be found in a letter from Father Baltazar Dias, written in 1559 (54) which makes it evident that the Portuguese missionaries held great authority in these islands.

The Dutch invaded Kupang on the extreme west of Timor in 1651. They incited King Amavi and King Amanense (local chiefs) to kill the tiny number of Portuguese who were on the island (55). This created a rift between the natives and eventually led to a resistance struggle by the locals against the Dutch. The Dutch tried to end this uprising by repeatedly invading Batavia. The local resistance was initially led by the King of Oé-Cussi, Mateus da Costa. Later he was joined by António Hornay (born in Timor), and Simão Luiz (from Larantuca in the island of Flores). Simão Luiz was named "Captain Major of the South" by Viceroy António de Melo e Castro. After various incidents António Hornay became the undisputed leader from 1672 to 1696. Noticing that the State of India was weak, António Hornay decided to place a powerful political and economic autonomy under Portuguese Sovereignty. He monopolized all the business in the islands of Solor and Timor and sent the Viceroy his contribution for the defence of the State in gold. When the King of Portugal sent the Governor of India a letter in 1690, requesting the opinion of his Council on the use of the islands of Solor and Timor, António Hornay became the centre of attention in the State of India. The opinions which were expressed at this time (1691) reflect the situation of total abandon in which the possessions of the Portuguese Crown in the Orient found themselves. They also reflect António Hornay's extraordinary political awareness. He was possibly the most lucid amongst the first champions of local autonomy within the Portuguese colonies whose structure was, at that point, not ready to understand the legal and political potential of this progressive ideology.

CONCLUSION

These facts and documents speak for themselves of this tragic age for the Orient, victim of violent attacks from Europe carried out in the name of a common god and of varied kings. Of all the European nations to traverse the seas in search of the fabulous Orient, only Portugal displayed a more lasting interest than the simple, highly profitable economic exploitation, achieved through military superiority which was carried out by most of the European countries in Asia. In contrast to this Portugal's influence was felt in a wide variety of human activities - legal, social, religious, political, linguistic, artistic, scientific, cultural, humanitarian among the most important; activities which no other country repeated in Asia".

It can be concluded that the Portuguese voyages and navigations not only benefitted Portugal through the contact they had with the Orient but they also created an extensive cultural exchange between Portugal and the East which brought some benefits, more or less diffuse, to various coastal societies in the East.

NOTES

(1)Garcia de Resende: Cancioneiro Geral, Coimbra, 1910, pp. 177 - 183: Diogo Velho's "Da Caça que se Caça em Portugal", written in 1516.

(2)Diogo do Couto: Década VI, Lisbon, 1786, ch. 4, p. 7: "The Monarchs of Portugal at all times attempted to unite both spiritual and temporal powers to such an extent that one never functioned without the other".

Ferreira Martins: História da Misericórdia de Goa, Goa, 1910-1914.

Silva Rego, Rev. Prof. Dr.: Documentação Para a História das Missóes do Padroado Português do Oriente, Lisbon, 1947-1956.

de Sá, Rev. Dr. A. B.: Documentação Para a História das Missóes do Padroado Português do Oriente, Lisbon, 1954-1956.

Livro das Monções, ed. Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, Lisbon, 1974, bk. 1, ff. 103 - 127: "Regimento dos Memposteiros Mores e Memposteiros Pequenos para a Rendiçao dos Cativos" written on the 3rd of January, 1562.

(3)Lopes de Castaneda, Fernão: História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses, Lisbon, 1551, bk. 1, ch. 67: a letter from the King of Cochin (Iterama Maratinquel Unirramacoul Trimunparti) in which he declares his thanks to the King of Portugal and ennobles Duarte Pacheco Pereira by giving him a coat of arms, probably the only event of its kind in the history of the Orient.

(4)See the "Vimioso Collection" in the National Library of Lisbon, ms. 7638, doc. 35, ff. 61 - 64: a copy of a letter which "King Dom Manuel wrote to the King of Calicut and sent via Pedro Álvares Cabral, captain of the first fleet to go to India after its discovery by Vasco da Gama" on the 1st of March, 1500.

Silva Rego: ob cit. vol. I, doc. 4, pp. 15-21.

(5)Silva Rego: Portuguese Colonisation in the 16th Century: A Study of Royal Ordinances, Johannesburg, 1959.

(6)Silva Rego: Documentação para a História das Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente, Lisbon, 1958, vol 12, pp. 62-66.

(7)Gaspar Correa: Lendas da Índia, Lisbon, 1858, tome 1, vol I, pp. 220-232.

Silva Rego: ob cit, vol II, doc. 91, pp. 256-261: a letter from Dom João da Cruz to Dom João III, written in Cochin on the 15th of December, 1537.

(8)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol XII, pp. 37-56.

(9)Silva Rego: O Padroado Português do Oriente, Lisbon, 1940, pp. XV- XXIV of the Introduction and pp. 3 - 30.

(10)Silva Rego: Documentação para a História das Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente, idem, vol II, doc. 89, pp. 247- 248: a letter from Pedro de Sousa de Távora to Dom João III, written in Rome on the 12th of April, 1537.

(11)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 8, p. 44: a letter from S. Francisco Xavier to S. Inácio de Loyola, written in Goa on the 20th of September, 1542.

(12)See Cartas de Afonso de Albuquerque, Lisbon, 1884, tome 1, Carta IX, pp. 44 - 45: a letter written from Afonso de Albuquerque to D. Manuel on the 1st of April, 1512.

(13)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 1, pp. 8 - 9, note 6: a letter from Dom Sebastião to the State of India.

(14)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 69, p. 334 and vol II, doc. 96, pp. 293-308.

(15)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol II, doc. 75, p. 356 (Regulations of the College of Saint Paul).

(16)Silva Rego: Documentação Ultramarina Portuguesa, ed. Gulbenkian II, Lisbon, 1960, pp. 541 - 543, "Conquista da Índia per humas e outras armas reaes e evangélicas", from the "Egerton Collection" in the British Museum, Codex 4, bk. 4, ch. 7, ff. 188 - 190, 1646.

Almeida Calado: "Documento Seiscentista", Brotéria, January, 1957.

(17)Silva Rego: Documentação para a História das Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente, idem, vol III, doc. 108, p. 517: a letter from the Chapter of the Cathedral of Goa to the King of Portugal, written on the 15th of October, 1547.

(18)Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 52, p. 188: a letter from Father Nicolau Lanciloto to Father Martinho de Santa Cruz in Coimbra, written in Goa on the 22nd of October, 1545.

(19)Silva Rego: Documentação Ultramarina Portuguesa, ed Gulbenkian II, pp. 543 - 546.

(20)Lopes, David: A Expansão da Lingua Portuguesa no Oriente nos Séculos XVI, XVII e XVIII, Porto, 1969: Portuguese was the language most Europeans learnt first to qualify them for general conversation with one another as well as with the different inhabitants of India. Throughout the eastern seas, nearly every European trading factory found it necessary to employ at least one Luso-Indian Christian professional interpreter and 'writer' of Portuguese. The language was more widely spoken in Batavia than Dutch, and in Madras and Bombay more widely than English..."

Hamilton, Captain Alexander: A New Account of the East Indies, re-edited by Argonaut Press, 1930, p. 7. Dalgado, Monsig. S. R.: Influência do Vocabulário Português em Línguas Asiáticas, Coimbra, 1913.

(21)Silva Rego: Documentação para a História das Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente, idem, vol III, doc. 108, p. 520: a letter from the Chapter of the Cathedral of Goa to the King of Portugal, written in 1547.

(22)Dalgado, S. R.: ob cit, pp. 116 - 117.

(23) idem, p. 131.

(24)idem, p. 33.

(25)Watt, Sir George, C.I.E., C. M., L.L.D., F.L.S.: The Commercial Products of India, London, 1908, p. 320.

(26)Colthurst, Ida, F.H.S., F.Z.S.: Familiar Flowering Trees in India, Calcutta, 1937, pp. 83 - 86.

(27) de Goes, Damião: Crónica do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel, part III, ch. 4, pp. 185 - 193 and part IV, ch. 18, pp. 43 - 48: "jaguars, lions and elephants, monsters and talking birds, porcelain, diamonds, all of these were commonplace...".

Garcia de Resende: ob cit, see note 1.

Gaspar Correa: ob cit.

(28) Dalgado, S. R.: ob cit, p. XVIII of the Introduction.

(29) Colthurst, Ida: ob cit, p. 51 and p. 85.

(30)Vieira Velho, Selma: A Influência da Mitologia Indiana (Hindú) na Literatura Portuguesa nos Séculos XVI e XVII, (doctoral thesis at the University of Bombay), ch. 8.

(31)Singh, Dr. Sham; Krishnamurthi, Dr. S. and Katyal, S. L.: Fruit Culture of India, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, 1963, pp. 184 - 191.

(32) idem, pp. 175-183.

(33) idem, pp. 155-164.

(34) Watt, George: ob cit, p. 1028.

(35) Singh, Dr. Sham et al: ob cit, pp. 192 - 198. Ambekar, G. R.: The Crops of the Bombay Presidency, Department of Agriculture of Bombay, Government Central Press, Bombay, 1933, part II, p. 110.

(36) Watt, George: ob cit, pp. 264 - 266.

(37) idem, pp. 1132-1139.

(38) idem, pp. 65-66.

Singh, Dr. Sham et al: ob cit, p. 372.

Garcia da Orta: Coloquios dos Simples e Drogas da Índia, ed. Imprensa Nacional, Lisbon 1891, Coloquio Quinto.

(39) Dalgado, S. R.: ob cit, p. 4.

(40)Livro das Monções, idem, bk. 55B, f. 348.

(41)Cunha Rivara: Arquivo Português Oriental, f. 2, p. 4, doc. 1 art. 5.

(42) dos Santos, Reynaldo: O Império Português e as Artes; Oito Séculos de Arte Portuguesa; A India Portuguesa e as Artes Decorativas; A Torte de Belém; 0 Manuelino.

Keil, Luís: Ourivesaria Portuguesa dos Séculos XII a XVII; Porcelanas Chinesas do Século XVI com Inscrições em Português; Faianças e Tapeçarias; Alguns Exemplos da Influência Portuguesa em Obras de Arte Indiana.

da Silva Couto, João Rodrigues: Os Cálices na Ourivesaria Portuguesa do Século XII ao Século XVIII; Alguns Subsídios para o Estudo Técnico das Peças de Ourivesaria, no Estilo Denominado Indo-Português; A Prataria Indo-Portuguesa; A Arte da Ourivesaria em portugal.

de Vasconcelo, Joaquim: A Pintura Portuguesa nos Séculos XVI e XVII; Da Arquitectura Manuelina; História da Ourivesaria e Joelharia Portuguesa.

Souza Viterbo: O Orientalismo em Portugal no Século XVI; A Exposição da Arte Ornamental.

Saldanha, Mariano: "A Cultura da Música Europeia em Goa", Revista Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos, Lisbon, 1956, vol VI, p. 3.

Rodrigues, Lúcio: The Mando - A Look Before and After in Soil and Soul in Konkani Folk Tales, Bombay, 1974.

(43) Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 54, p. 203.

(44)See Cartas de Afonso de Albuquerque, idem.

(45) Silva Rego: ob cit, vol III, doc. 54, p. 208.

(46)Silva Rego: "1622 - Ano Dramático na História da Expansão Portuguesa no Oriente e no Extremo Oriente", Memórias da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, Lisbon, 1977, tome 18, p. 33.

(47)Silva Rego: O Padroado Português do Oriente, Lisbon, 1940, p. 11.

(48) idem, pp. 63 - 64.

(49) idem, p. 41.

(50)Silva Rego: Raízes de Goa, Lisbon, 1969; "Os Ingleses em Goa", off-print from Estudos Políticos e Sociais Lisbon, 1965, vol III, no. 1.

(51) Lopes, David: ob cit, pp. 9 - 53.

(52) idem, pp. 51 - 53.

(53) de Sá. A. B.: ob cit, vol I, doc. 9, pp. 66 - 74.

(54) idem, vol II, doc. 54, pp. 344 - 348.

(55) Livro das Monções, idem, bk. 55B, ff. 265 - 293.

*Doctorate in Portuguese Literature from the University of Bombay (St. Xavier's College); researcher on the Portuguese presence in the Orient and on Hindu influences in Portuguese literature of the 16th C..

start p. 84

end p.