§ 1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. STATEMENT OF SUBJECT

The Portuguese settlement in Macao has been established for over four-hundred years. During this period, the Western culture brought about by the Portuguese came into contact, and consequently, intermixed with the Oriental culture of the Chinese. In the pages of the present study, an attempt is made to survey these mutual influences in the field of architecture, with regard to the ideas and characteristics that make up the special type of architecture as found only in Macao.

1.2. REASON FOR SELECTION OF SUBJECT

The architecture in Macao represents a side branch in the architectural development of the Orient; it is the link between two different types of architecture: the Oriental and the Western. The many fine buildings in Macao are specimens of a special type of architecture with the characteristics of both Chinese and Portuguese architecture. With the coming of modem redevelopment, they are now fast disappearing, and it would be more and more difficult for a research on these mutual influences in the future.

1.3. CONTRIBUTION IT IS HOPED TO MAKE

The study would reveal the way by which the Chinese and the Portuguese have successfully adopted the good qualities of their own architecture, and combined them into a functional and harmonious style, particularly suitable for the conditions in Macao. At present the development of Chinese architecture has almost come to a standstill. Unlike the case of Japan, the modem Western architectural philosophy and technology have not been well assimilated into the traditional Chinese architecture. The architecture of Macao can serve as an example of how this was achieved in the past. With the analyses made after the study, a similar approach may be worked out in the near future, leading to the ultimate modernisation of Chinese architecture.

1.4. METHOD OF RESEARCH

The research is conducted mainly by observation and reference -- observation for the characteristics of the existing buildings, and reference for their history. By determining the age of the buildings, the sequence of the different stages in the development of Macao architecture can be worked out. The specimens are then analysed with regard to plan, construction and decoration. Thus it can be found out how the mutual influences of Chinese and Portuguese architecture affect the architecture of Macao.

The study is mainly concerned with those examples where both Chinese and Portuguese influences are found. Particular attention is being paid to those examples erected in the earlier period, and now rapidly decreasing in number.

The period designated for the study extends from the earliest time before the coming of the Portuguese to Macao (i. e., before 1557) up to 1937, the start of the Second World War in Asia. The study on the pre-Portuguese period is intended to give a picture of what the local architecture in Macao was like without any Portuguese influences. The year 1937 may be considered as the latest limit in the development of Macao architecture under the mutual influences. By this time, both Chinese and Portuguese influences had virtually disappeared, their previous predominance being taken over by the modem international style of concrete construction. The majority of the buildings erected after the Second World War are generally of low quality, and very often, entirely out of tone with the architectural character of Macao. Hence, the period after the start of the Second World War is excluded from the study.

1.5. TERMS OF REFERENCE

In this Report 'Macao Architecture' is considered as that special type of architecture with both Chinese and Portuguese characteristics, as found in Macao. It generally excludes those buildings purely Chinese or Portuguese in architecture.

The term 'Portuguese Architecture' in here interpreted as including all the European influences in Macao. Basically,' Portuguese Architecture' is not a distinctive style of its own; it is a mixture of various foreign influences, Moorish in the earlier period, and the Italian in the later days. With the exception of certain characteristic features, it is largely in common with the architecture found in the Mediterranean countries of Europe.

§ 2. PART I: GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF MACAO

2.1. GEOGRAPHY OF MACAO

2.1.1. POSITION AND SIZE

The Portuguese administered Territory of Macao stands on the western shore of the Zhujiang (Pearl River). The Guia Lighthouse, on Macao's highest hill [Guia Hill], is on the co-ordinates of 22° 11' 51" N., and 113°32' 48" E. This Territory consists of a peninsula on which was built the city of Macao, with the Islands of Taipa and Coloane to the south. The peninsula is about 3 miles in length and 1 mile at its widest part, being joined by a narrow isthmus to the Island of (Guang: Chung Shan). The total area is approximately 6 square miles, with the peninsula occupying 2.1 square miles, Taipa 1.4 square miles, and Coloane 2.5 square miles. The highest point is the Coloane Height (Alto de Coloane) at 685 ft.

2.1.2. PHYSICAL FEATURES

Macao peninsula is irregular in form, being 8 miles in circuit, with a number of small hills, namely Colina de Guia (Guia Hill) and Colina de Penha (Penha Hill). One side of the peninsula is carved into a semi-circular bay, known as the Praia Grande (Pray a Grande); the other side with the Ilha da Lapa (Lappa Island) opposite forms the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour). The soil of Macao is granitic. The reclamations around the city and at Taipa have resulted from alluvial deposits.

2.1.3. CLIMATE

The climate is tropical monsoon, with a mean annual temperature of over 20℃ [Centigrades]. The humidity is high, ranging between 75% and 90%. Precipitation is also high, varying from 40" [inches] to 80", coming mainly between April and September, often accompanied by typhoons. The hottest month is July, with an average temperature of 28.3℃, while the coldest is January, with 14.6℃. The month with the greatest humidity is April, the driest being October and November.

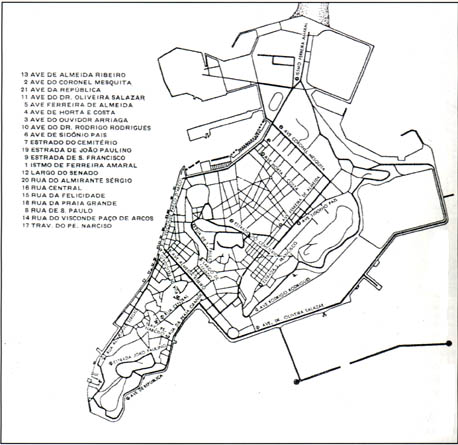

[MAP OF MACAO].

[Ca1970].

In: WONG Shiu Kwan, Macao Architecture/An Integrate of Chinese and Portuguese Influences, Offprint nos 2-3 of the "Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões", vol. 4, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1970, p.13 -- hereafter: Macao Architecture.

[MAP OF MACAO].

[Ca1970].

In: WONG Shiu Kwan, Macao Architecture/An Integrate of Chinese and Portuguese Influences, Offprint nos 2-3 of the "Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões", vol. 4, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1970, p.13 -- hereafter: Macao Architecture.

2.1.4. POPULATION

According to the 1960 Census, the population of Macao totals 169,229 of whom 160,764 are Chinese, 7,074 Portuguese, and 561 others. Of the Portuguese inhabitants, 5,119 were born in Macao, 1,080 hailed from Portugal, 1,178 from the other Portuguese administered Overseas Territories, and 597 born elsewhere. At present, due to the influx of people from the neighbouring countries, the population of Macao is estimated at 280,000.

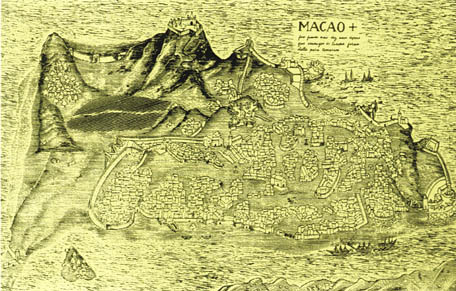

Macao in 1632 -- probably the earliest picture of the place.

After a picture in Antonio Bocarro's Livro do Estado da India Oriental.

In: Macao Architecture, p.20.

Macao in 1632 -- probably the earliest picture of the place.

After a picture in Antonio Bocarro's Livro do Estado da India Oriental.

In: Macao Architecture, p.20.

2.2. HISTORY OF MACAO

2.2.1. BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE

Macao was used as a port long before the coming of the Portuguese. The harbour offered an excellent shelter in stormy weather, and was used by fishing crafts as well as trading junks. The Hakka, original natives from Shandong, settled in and around Macao during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Traders from Fujian and the Léquias (Liuqiu Islands) began to use this port during the Yuan dynasty (1278-1368). The earliest known settlers in Macao were two small families from Fujian, one with the surname of Tsum and the other Ho, who made their homes in the Mong Ha [Guang.:] valley. The legend attributed to Neang Ma, the patroness of the seafarers, dated from the early days of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The shrine subsequently erected at the entrance to the port gave the name 'A Ma Kao' to the place, which was later adopted by the Portuguese pioneers for their new settlement.

2.2.2. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SETTLEMENT

Portugal was the first European nation to establish colonies and trading posts in the Orient. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, she had acquired settlements on the coasts of East Africa and India, with Goa as the main centre of trade. Through Afonso de Albuquerque, one of the first Governors of Goa [ i. e., Portuguese India], the Portuguese initiated an eastward expansion of trade to China. The capture of Malacca I presently Melaka] in 1511 intensified the development of the scheme. As early as 1513, Jorge Álvares led an expedition across the South China Sea, and placed a padrão at Tamão (Tunmen), the Island of Lintin [Guang.], near Nanton (Guang: Nam Tau).

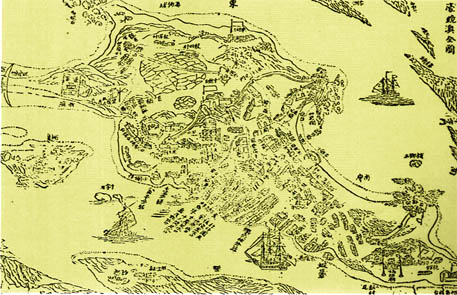

[The peninsula of Macao].

Reproduced from Hsiang-Shan Hsien-Chih. Print.

Former Luís Gonzaga Gomes collection.

In: Macao Architecture, p.22.

[The peninsula of Macao].

Reproduced from Hsiang-Shan Hsien-Chih. Print.

Former Luís Gonzaga Gomes collection.

In: Macao Architecture, p.22.

In 1517, the Portuguese Embassy under Tomé Pires was sent to China to establish relations with the Chinese. However, misunderstanding with the local Chinese officials led to hostility between the two people. Meanwhile, another expedition under Martim Afonso de Melo Coutinho was attacked by the Chinese fleet at the mouth of the Pearl River in 1522. Ultimately, both attempts failed without any achievement. Nevertheless, in time, trading occurred at various places on the coasts of Guangdong, Fujian and Zhejian, as far north as near [Liampó] (Ningbo) without the official approval of the Chinese authorities.

In 1554, Leonel de Sousa, a Portuguese Captain, concluded an Agreement with the Chinese, whereby permission was granted for the Portuguese to trade in South China. Goods were exchanged during the months from August to November on the Island of Sanchuão or São João (Shanchuan Dao; or St. John's Island) fifty miles southwest of Macao. Temporary straw and bamboo huts were erected for the Portuguese, and were usually destroyed when they departed. Between 1554-1555, this "Fair" was moved to (Lampacau) Langbaijiao which was used until 1560, when as many as five to six-hundred people had settled there.

The Portuguese first reached Macao in 1534, to dry the goods which were damaged during the typhoon. By 1553, temporary trading sites were set up in Macao, and in order to get special facilities for themselves, the Portuguese offered an annual ground rent of five-hundred taels of silver to the Chinese authorities. In 1557, as a reward for the extirpation of the pirates who infested this part of the South China coast, the Portuguese were given the permission to build their permanent residences in Macao. The year 1557 is generally considered as the date for the founding of the city of Macao by the Portuguese.

The Praya Grande, Macau, 1841.

T. ALLOM.

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 2, p.45: Macao Architecture, p.25 -- top.

The Praya Grande, Macau, 1841.

T. ALLOM.

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 2, p.45: Macao Architecture, p.25 -- top.

2.2.3. THE ORIGIN OF THE NAME

Long before Macao came into the story of the early Sino-Portuguese relations, the place was known as 'Kum Tau Im Chong' [Guang.], meaning 'Salt-pan of the Golden Basket'. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) it formed part of the District of Xiangshan, and was then known as 'Haojing' (Guang.: 'Hou Keng'), meaning 'Mirror of the Oyster', or 'Hoi Keng' [Guang.], meaning 'Mirror of the Sea'. These variations are all linked with the famous bay, now called (Praya Grande), which forming such a pleasant circle, reminded some poetically minded Chinese officials of a mirror. The most common name now used is 'Aomen', meaning 'Gateway to the Sea-Mirror Bay'.

The Portuguese version is derived from the term 'A-Ma-O', or 'A-Ma-Cao', meaning 'Bay of Ama', the goddess of the Fujianese sailors. The old temple dedicated to this Goddess at the entrance of the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour) antedates the coming of the Portuguese pioneers. The first Portuguese settlers of 1557 called their home 'Povoação do Santo Nome de Deos de Amacao na China', (Settlement of the [Holy] Name of the God of Macao in China). [sic] In 1586, the status of a city was granted by the Indo-Portuguese authority at Goa with the official name of "Cidade do [Santo] Nome de Deos na China" ("City of the [Holy] Name of God in China "). However, this never became popular, and the name of the Chinese Goddess continued to be perpetuated in the more usual form of 'Macao'.

2.2.4. EARLY PERIOD, SIXTEENTH CENTURY

At the outset, the Portuguese were somewhat hesitant about any intensive development of Macao. There were doubts to the safety or permanence of the settlement, and both Shanchuan Dao and Langbaijiao were still frequently used by traders. Nevertheless, the early years of the settlement saw the erection of warehouses, residences, civic and ecclesiastic buildings, which were eventually followed by forts and barracks. By 1563, the population, originally some five hundred Portuguese, increased to nine hundred, exclusive of children, besides Mallacans, negroes, and other detainees, when settlers from Langbaijiao moved over to Macao.

View of the town and harbour from the hillside under the Guia Fort, 1840.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 2, p.27; Macao Architecture, p.25 -- bottom.

View of the town and harbour from the hillside under the Guia Fort, 1840.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 2, p.27; Macao Architecture, p.25 -- bottom.

More and more Chinese came into Macao to do business with the Portuguese. They generally lived in their own villages or in houses set up on the outskirts of the city. The two people had friendly dealings with each other. In 1573, the Chinese authorities resolved to build a wall across the isthmus which separates Macao from the main-land. Within this limit, as early as 1587, a civil Mandarin was appointed to reside and govern the city in the name of the Emperor of China. The Portuguese were not allowed to build new churches or houses without a license from the Chinese authorities.

The early Portuguese settlers in Macao governed themselves and enjoyed complete personal liberty without any control or direction from the Indo-Portuguese Government at Goa. In 1586, the place was granted the status of a city by the Viceroy, and a few judicial officers were appointed by the authorities at Goa. A democratic form of municipal administration was evolved. The citizens elected representatives, who in their turn nominated three residents as Aldermen. These three, together with three local Legal Officials and a Secretary formed the Leal Senado (Senate/Municipal Council), in whom the governorship of the city was really vested.

The position and security which the city enjoyed resulted in its selection as a centre for religious activities in the Far East. In 1575, the Diocese of Macao was established by Papal Bull.

The early town form was dictated by a ridge high ground running from the north-west to the south-west, and it was on this spine that the main road system developed. The northwestern area adjacent to the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour) was the site of the first development. The south-western section developed after 1590 and grew in the vicinity of the parish Church of São Lourenço (St. Lawrence's).

2.2.5. THE GOLDEN AGE: SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

The trade with Japan at the beginning of the seventeenth century contributed to a large extent to the extraordinary prosperity which spurred the quick growth of the city. The Portuguese became the principal intermediaries and carriers of trade between China and Japan. At the same time, there was also a profitable trade carried on with the Philip-pines in Chinese goods. Enormous fortunes were made, and the subsequent prosperity aroused the interests of the Dutch and Spaniards on the city.

In 1622 the Dutch assaulted Macao, but were driven off with heavy casualties. This event also disturbed the Chinese, and induced the Chinese authorities to permit the Portuguese to fortify the city.

By 1630, the population of Macao consisted of 437 Portuguese and Eurasians, and 403 native Christians, exclusive of women and children and Chinese. The Chinese population at this time was about ten-thousand; and if to these were added the large number of slaves, the total figure would be between fifteen and twenty-thousand.

The city boundary was defined by strong walls erected between the Fortaleza de São Paulo (Fortress of St. Paul's) and the sea. Nearly all level sites had been occupied. Large, open squares were retained near the churches and public buildings. Development grew up at the Praia Grande (Praya Grande) along the waterfront, and gradually spread towards the centre of the city. Control was exercised on building materials, which had to be fire-proof. There were six convents and monasteries, with three parish Churches, name Sé (Cathedral), São Lourenço (St. Lawrence's) and Santo António'(St.Anthony' s), the chapel of São Lázaro (St. Lazarus') being built outside the city for the lepers.

In 1639, the Portuguese were driven out of Japan. The loss of the Japanese trade was compensated to some extent by new markets in Timor and Macassar [presently Makasar]. The restoration of King Dom João IV to the Portuguese throne in 1640 resulted in the disruption of the trade with Manila. Although the peace of 1668 between Portugal and Spain renewed the trade, the profits had diminished considerably. The blocade of the Malacca Strait by the Dutch virtually cut off Macao from Portugal. In 1685, the Emperor Kangxi (r.1662-†1722) opened Chinese ports to foreign trade, a measure which was unfavourable to Macao. The Mandarins sought to enfranchise Macao as a Chinese port, and the Hebo [Guang.: Hopu] (Chinese Customs Commissioner), was sent to Macao in 1688. Here officials collected duties on all shipment of goods from Guangzhou. This gave a fatal blow to the economy of Macao. A period of depression followed; Macao was falling off from its ancient splendour.

2.2.6. THE DECLINE: EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES

On the opening up of the Chinese trade, an increasing number of foreign merchants, including those of the British East India Company, established their offices and residences in Macao. Meanwhile, Portuguese trade itself was almost exclusively confined to the Siamese market. Portuguese shipping ceased to be an essential factor in the city's economy.

In 1831, a typhoon struck Macao and destroyed many houses at the Praya Grande (Praya Grande). The Church of Nossa Senhora da Penha de França (Our Lady of Penha de França) and the Sé (Cathedral) were severely hit, and it took some time before the damages could be repaired. This was succeded by a disastrous fire, which burned down over four-hundred buildings, mainly in the Chinese quarter of the city. In 1835, another tragedy occured with the destruction by fire of the most celebrated building in Macao, the Church of São Paulo (St. Paul's), of which only the façade survived.

From about 1850 onward, the Portuguese population increased very slowly, in comparison with the Chinese community. In 1835, the population of Macao was estimated at 34,628, which was made up of 4,628 Portuguese and other Europeans, and 30,000 Chinese of whom 13,000 were Christians. No permanent industry existed. The revenue was mainly raised by gambling monopolies. Many of the great houses of the former wealthy Macao merchants fell into neglect, or became the crowded dwellings of the poor. A major development occured from 1850 onwards in the western part of the city between the Rua do Seminário (Seminary Street) and the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour). This area had been only sporadically developed during the seventeenth century. Most of the new buildings were small. The old city gates and their adjacent walls were demolished to allow for residential expansion towards the Portas do Cerco (Border Gate or Barrier Gate).

In 1874 another typhoon struck Macao, causing damage to innumerable houses in the Chinese quarter, so much so that many of them had to be completely renovated.

In 1880, industry was established at the isthmus adjacent to Ilha Verde (Green Island), where a cement factory was opened. Small metal-work and ironmongery shops also appeared. From the end of the nineteenth century, it became obvious to the Macao authorities that if Macao was to prosper again, new harbour facilities were required. As a result of this, many of the projects considered between 1890 and 1910 were concerned with the dredging and reclamation of areas for new Porto Exterior (Outer Harbour) installations.

2.2.7. THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

In 1910, the work of the new Porto Exterior (Outer Harbour) installations commenced, but was interrupted by the First World War (1914-1918).

In 1921, the work was resumed, and the government of Portugal provided the financial support. The proposal involved the construction of an outer harbour and ancillary maritime installations, which would cover an area of about one-hundred and forty acres. Ten million Patacas were allocated to the project, and the contract was awarded to the Netherlands Harbour Works Company. By 1923, a four-mile channel had been dredged from the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour) to the sea, and a breakwater was completed in 1926. The reclamation project resulted in the creation of a new Porto Exterior (Outer Harbour) and the acquisition of a large area of land in the southeast, which would eventually provide the much needed sites for civic and residential buildings.

In 1910, the population of Macao was 74,866, of whom 71,021 were Chinese, 3,061 Portuguese, and 244 others. The outbreak of the civil disturbances in China, followed by the spread of the Second World War after 1937, led to a rapid rise of population to 245,194 in 1939. There was a considerable strain on the existing accommodation and the available building sites.

In 1941, refugees further added to the difficulties. However, Macao remained neutral in the Second World War, and was spared from Japanese occupation.

Macao is a unique city, embracing both Chinese and Portuguese in a cosmopolitan community. Endowed, as it is, with such limited resources, it continues to survive. Its character remains intact; it was sufficiently well developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and is rich with the architectural heritage of its glorious past.

§3. PART II: THE DEVELOPMENT OF MACAO ARCHITECTURE

The evolution of Macao under the mutual influences of Chinese and Portuguese architecture can be roughly divided into four periods as follow:

A. Before 1557 -- That is before the coming of the Portuguese and the establishment of any permanent Portuguese settlement in Macao, there being no Portuguese influence involved in the local architecture;

B.1557-1700 -- The early period with little mutual influences of Chinese and Portuguese architecture, Portuguese influence being generally prevalent in Macao;

C.1700-1900 -- The year 1700 roughly marking the beginning of the climax in the development of the mutual influences, Chinese and Portuguese architecture being fused into a special style;

D.1900-1937 -- The introduction of rein-forced concrete to Macao and the rise of the Inter-national Style, with the decline of the mutual influences to virtually non-existent by 1937.

3.1. BEFORE 1557

Before the coming of the Portuguese, the little peninsula now known as Macao was the home of a few fisherfolk, with a number of matsheds clustered near the two temples, which were then in existence. Today, these two temples can still be seen in good conditions; they are the Ma Kok Miu (Ama Temple) and the Kun Yam Miu [Guang.].

The Ama Temple, Macao.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 1. p.66; Macao Architecture, p.34--top.

The Ama Temple, Macao.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 1. p.66; Macao Architecture, p.34--top.

The Terrace and shrines in the Ama Temple.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 1, p.68; Macao Architecture, p.34 -- bottom.

The Terrace and shrines in the Ama Temple.

T. ALLOM

Coloured print.

In: The Chinese Empire, 2 vols., 1858, vol. 1, p.68; Macao Architecture, p.34 -- bottom.

Ma Kok Miu (Ama Temple) as it is today.

Photograph taken in the late Sixties.

In: Macao Architecture, p.35.

Ma Kok Miu (Ama Temple) as it is today.

Photograph taken in the late Sixties.

In: Macao Architecture, p.35.

3.1.1. MA KOK MIU (AMA TEMPLE)

The Ama Temple was originally a simple shrine, dedicated to the Goddess Neang Ma, the patroness of the seafarers in Fujian. It was first erected in the early days of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The existing complex of the Temple dates from the construction during the reign of Wanli (r.1573-†1621). Wether the present form of the Temple is an exact reproduction of the one antedating the coming of the Portuguese to Macao is unknown, as very few records of the place before 1557 are available. However, the fact that the Temple has been sacredly preserved in its original form for over four hundred years, it may be assumed that the present complex somehow retains the main characteristics of the pre-Portuguese building, if not the whole of it. Hence, the Ama Temple may be considered to be an example of Macao architecture, antedating the coming of the Portuguese, and therefore, free from any Portuguese influence.

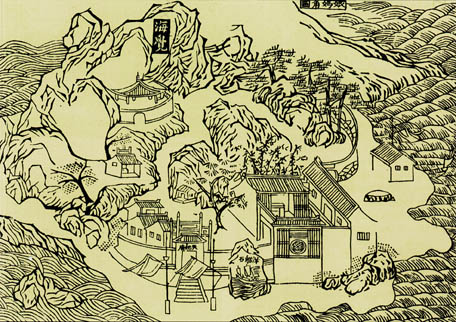

Ma Kok Miu (Ama Temple), in 1746.

Appears much the same as it is nowadays.

The two flag-poles in front of the Temple no longer exist. The rock in the foreground is carved with the junk miraculously saved by the Goddess Ama.

In: TCHEONG-Ü-Lâm [YIN Guangren] -IAN-Kuong-Iâm [ZHANG Rulin], Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Aomen jilüe]: Monografia de Macao [Macau Monograph], (Edição da Quinzena de Macau [..], Lisboa), Macau, [Leal Senado] Tipografia Martinho, 1979, ill. opp. p.90 -- hereafter: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; WONG, Macao Architecture, p.33.

Ma Kok Miu (Ama Temple), in 1746.

Appears much the same as it is nowadays.

The two flag-poles in front of the Temple no longer exist. The rock in the foreground is carved with the junk miraculously saved by the Goddess Ama.

In: TCHEONG-Ü-Lâm [YIN Guangren] -IAN-Kuong-Iâm [ZHANG Rulin], Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Aomen jilüe]: Monografia de Macao [Macau Monograph], (Edição da Quinzena de Macau [..], Lisboa), Macau, [Leal Senado] Tipografia Martinho, 1979, ill. opp. p.90 -- hereafter: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; WONG, Macao Architecture, p.33.

The Ama Temple is situated on a romantic site at the entrance of the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour) of Macao. It leans against a rugged mountain, known as the Colina da Barra (Hill of the Bar [better known as Colina da Penha (Penha Hill)]), and is composed of three parts, arranged in the midst of boulders and trees.

The front part of the complex is defined by an enclosure of dwarf walls connecting the various boulders of granite. Behind the entrance porch is a small courtyard which gives access to the principal building of the complex dedicated to the Godess, 'Ama' or 'Neang Ma'. A flight of steps, winding up the hill side, lead to two other buildings, the higher one dedicated to Kun Yam, the Goddess of Mercy, and the lower one to the God of Great Benevolence [Hongren]. The buildings have structural gable walls supporting a timber roof. The roofs are covered with glazed tiles with characteristic Chinese upturned eaves. The walls are stuccoed and painted in red and green.

3.1.2 KUN YAM TONG (KUM YAM TEMPLE)

The older of the two Temples in the Kun Yam Tong, situated in Mong Ha. It is known to exist in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in the form of a small sanctuary with a tiny altar, consecrated to Kun Yam (The Goddess of Mercy). Subsequent development and extension of the Temple took place in the Ming dynasty, and the present buildings date from 1627. The Temple was restored during the reigns of Jiajing (r.1796-†1821) and Tongzhi (r.1862-†1875). As with the case of the Ama Temple, no [written] records attest the form of the pre-Portuguese building. However, unlike the Ama Temple, the reconstruction in the later ages brought in Portuguese influences, particularly in the monastic buildings at the side of the Temple.

3.2. 1557-1700

The early settlers of Macao, including both Chinese and Portuguese, tended to build their houses in the same way as in their own native countries. They tried to maintain their traditional life in their new home. They were, as yet, still too fresh with the ideas and techniques of their new friends. However, as time went on, the use of local materials and the employment of the Chinese craftsmen in the work inevitably led to some Chinese influence on Portuguese architecture, such as in the roof construction and in the application of Chinese decorative features. Generally speaking, the mutual influences of this period were small, being more in the way of the Chinese influencing the Portuguese than vice-versa.

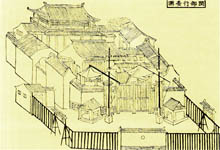

[Untitled].

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.74; Macao Architecture, p.37.

[Untitled].

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.74; Macao Architecture, p.37.

It was during this period that most of the churches in Macao were built. They are well maintained and preserved in their original forms without much changes. Some of the residential buildings can still be seen in certain parts of Macao, namely in the vicity of the Churches of Santo António (St. Anthony) and São Lourenço (St. Lawrence). They were strongly built with massive walls and heavy structural members, the majority of the surviving examples are predominantly Portuguese in architecture.

Lin Fong Miu (Lin Fong Temple) at Avenida do Almirante Lacerda [Admiral Lacerda Avenue].

Erected in 1592 and restored in 1876.

The Temple is typically Chinese in its architecture, with rich decorations in terracotta work. The plan is symmetrical and is similar to that of Kun Yam Tong [Kun Yam Temple].

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.166; Macao Architecture, p.39.

Lin Fong Miu (Lin Fong Temple) at Avenida do Almirante Lacerda [Admiral Lacerda Avenue].

Erected in 1592 and restored in 1876.

The Temple is typically Chinese in its architecture, with rich decorations in terracotta work. The plan is symmetrical and is similar to that of Kun Yam Tong [Kun Yam Temple].

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.166; Macao Architecture, p.39.

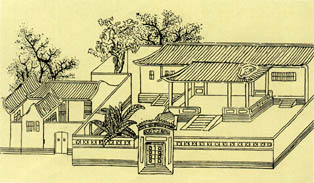

The headquarters of the Hopu [Hebo] (Chinese Customs commissioner) in Macao.

Erected in 1688 and demolished in 1849.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.38; Macao Architecture, p.40.

The headquarters of the Hopu [Hebo] (Chinese Customs commissioner) in Macao.

Erected in 1688 and demolished in 1849.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.38; Macao Architecture, p.40.

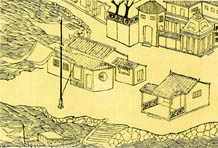

Shore office of the Hopu [Hebo] (Chinese Customs Commissioner) at the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour).

[Active between] 1688 and 1849.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.42; Macao Architecture, p.41.

Shore office of the Hopu [Hebo] (Chinese Customs Commissioner) at the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour).

[Active between] 1688 and 1849.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.42; Macao Architecture, p.41.

The Leal Senado (Senate House).

In the seventeenth century.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.44; Macao Architecture, p.42.

The Leal Senado (Senate House).

In the seventeenth century.

In: Ou-Mun Kei-Leok [Macao Monograph]; ill. opp. p.44; Macao Architecture, p.42.

3.2.1. SÃO PAULO (ST. PAUL'S CHURCH)

The collegiate Church of São Paulo (St. Paul's) was completed as early as 1603, with the present façade added between 1620 and 1637, and the steps built in 1640. The elements composing the façade are an extraordinary mixture of Medieval, Classical and Oriental forms. Local crafts, arts, and traditions have been infused into the features to express an entire sermon in stone to the worshippers. A large part of the work was done by Japanese Catholics in Macao, many of whom were experienced craftsmen.

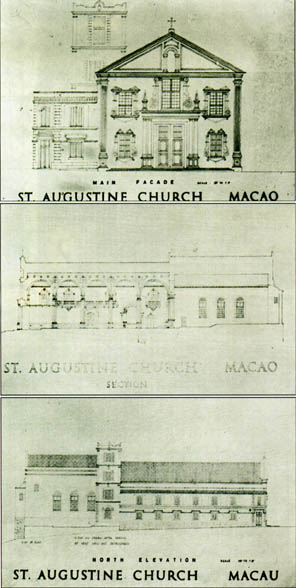

3.2.2. STO. AGOSTINHO (ST. AUGUSTIN'S CHURCH)

The Spaniards are said to have built it in honour of Nossa Senhora da Graça (our Lady of Grace), but having received orders to withdraw to Manila in 1589, the Portuguese friar succeeded. The church was repaired in 1814.

The character of the building is Iberian. The façade is decorated with elaborate stucco work, picked out in white against a background of a pastel shade of yellow. Windows and doors are painted green, offering a strong contrast on the façade. The roof is constructed of Chinese tiles upon a timber structure of fir poles in the round.

3.2.2. STO. AGOSTINHO (ST. AUGUSTIN'S CHURCH)

The Spaniards are said to have built it in honour of Nossa Senhora da Graça (our Lady of Grace), but having received orders to withdraw to Manila in 1589, the Portuguese friar succeeded. The church was repaired in 1814.

The character of the building is Iberian. The façade is decorated with elaborate stucco work, picked out in white against a background of a pastel shade of yellow. Windows and doors are painted green, offering a strong contrast on the façade. The roof is constructed of Chinese tiles upon a timber structure of fir poles in the round.

In: BRUNT, Michael Hugo, An architectural survey of the jesuitic seminary church of St. Paul's, Macao, in "Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong, 2 (1) 1954, plate X; Macao Architecture, p.43 -- top.

In: BRUNT, Michael Hugo, An architectural survey of the jesuitic seminary church of St. Paul's, Macao, in "Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong, 2 (1) 1954, plate X; Macao Architecture, p.43 -- top.

São Lourenço [St. Lawrence's Church], situated at Rua de S. Lourenço [St. Lawrence's Street].

On a little eminance in the heart of a residential district, is known to exist by 1618, the exact date of the foundation being unrecorded. ** Although the church was subjected to alterations and reconstructions through the ages, the main structure remains little changed since it was first built. Architecturally, the building is Iberian, with great care ande delicacy in its detail and decoration. It has a pitched Chinese tiled roof supported by timber trusses. Chinese terracotta panels are incorporated in the stone walls as decorative features.

In: Macao Architecture, p.45.

São Lourenço [St. Lawrence's Church], situated at Rua de S. Lourenço [St. Lawrence's Street].

On a little eminance in the heart of a residential district, is known to exist by 1618, the exact date of the foundation being unrecorded. ** Although the church was subjected to alterations and reconstructions through the ages, the main structure remains little changed since it was first built. Architecturally, the building is Iberian, with great care ande delicacy in its detail and decoration. It has a pitched Chinese tiled roof supported by timber trusses. Chinese terracotta panels are incorporated in the stone walls as decorative features.

In: Macao Architecture, p.45.

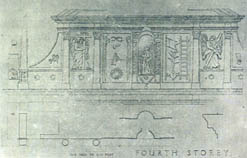

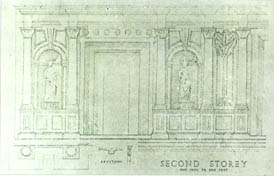

Sectional elevation -- Southwest.

Approximate Scale: 1 in = 18 ft.

In: BRUNT, Michael Hugo, The Parish Church of St. Lawrence of Macao, in" Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong, 6 (1-2) University of Hong Kong, 1961-1964, Plate XII; Macao Architecture, p.46.

Sectional elevation -- Southwest.

Approximate Scale: 1 in = 18 ft.

In: BRUNT, Michael Hugo, The Parish Church of St. Lawrence of Macao, in" Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, University of Hong Kong, 6 (1-2) University of Hong Kong, 1961-1964, Plate XII; Macao Architecture, p.46.

Igreja de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Church].

Main façade.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Igreja de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Church].

Main façade.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Igreja de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Church].

Ancillary tower adjacent to the Calçada do Tronco Velho (Alleyway of the Old Tree Stem).

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Igreja de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Church].

Ancillary tower adjacent to the Calçada do Tronco Velho (Alleyway of the Old Tree Stem).

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

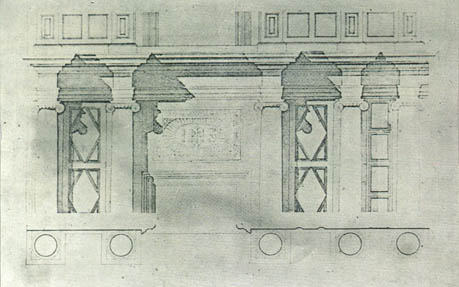

ST. AUGUSTINE CHURCH • MACAO

Main Façade / Section / North Elevation

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.47-48.

ST. AUGUSTINE CHURCH • MACAO

Main Façade / Section / North Elevation

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.47-48.

T'in H'au Miu [T'in H'au Temple], situated at Rua dos Pescadores [Fishermen's St.].

The temple was constructed during the reign of Guangxi (r.1875-† 1908) and restored in 1955.

In: Macao Architecture, p.50.

T'in H'au Miu [T'in H'au Temple], situated at Rua dos Pescadores [Fishermen's St.].

The temple was constructed during the reign of Guangxi (r.1875-† 1908) and restored in 1955.

In: Macao Architecture, p.50.

3.3. 1700-1900

This period marks the climax of the development of the mutual influences in Macao architecture. By 1800, a special style of architecture, with both Chinese and Portuguese characteristics had been evolved. The mutual influences had advanced beyond the mere limits of decorations and application of local materials to all the other aspects of the building. It was in domestic architecture that this special style was most prominent. Many fine examples of this period are still in existence, giving the special character to the city of Macao today.

The buildings which remain purely Chinese in architecture are the temples. They are generally very small, consisting only of the main hall, facing onto an open public square at the centre of a commercial/ residential district. Some are found at the outskirsts of the city.

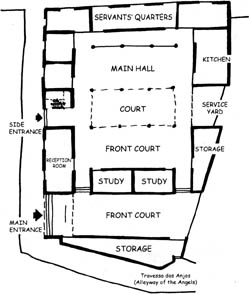

3.3.1. RESIDENCE AT TRAVESSA DOS ANJOS (ALLEYWAY OF THE ANGELS) no 24 --LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The plan follows the typical Chinese layout with the main halls in the middle and the rooms at the sides. The externall wall on the ground is pierced only with widely spaced windows, guarded with heavy iron bars, thus forming an enclosure around the house. The weight of the pitched roof is carried by the masonry walls and the row of timber columns around the central courtyard.

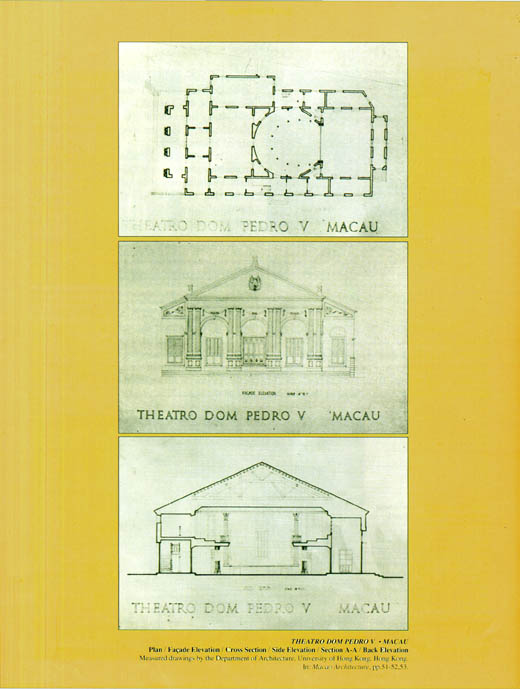

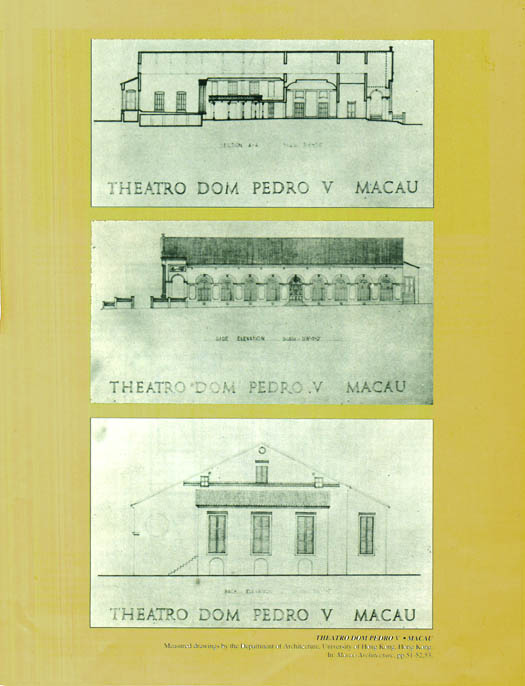

Theatro Dom Pedro V, at Rua de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Street].

Late eighteenth century.

The theatre forms part of the [Clube de Macau] Macao Club, which is the social meeting place of all the Portuguese residents of Macao. The entrance of the theatre is in Classical design, with a small court in front. The pitch roof consists of Chinese tiling supported by king-post trusses at the intermediate points. The weight of the roof rests on the arcades on either side of he building. On the whole Chinese influence on the civic buildings is comparatively small, compared with the residential buildings.

Text only in: Macao Architecture, p.51. Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Theatro Dom Pedro V, at Rua de Santo Agostinho [St. Augustine's Street].

Late eighteenth century.

The theatre forms part of the [Clube de Macau] Macao Club, which is the social meeting place of all the Portuguese residents of Macao. The entrance of the theatre is in Classical design, with a small court in front. The pitch roof consists of Chinese tiling supported by king-post trusses at the intermediate points. The weight of the roof rests on the arcades on either side of he building. On the whole Chinese influence on the civic buildings is comparatively small, compared with the residential buildings.

Text only in: Macao Architecture, p.51. Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

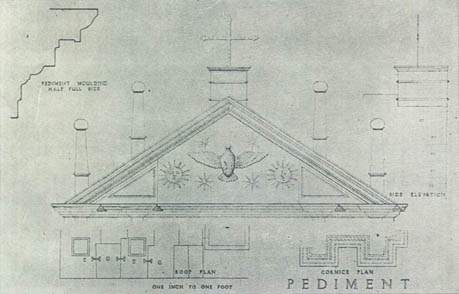

THEATRO DOM PEDRO V • MACAU

Plan / Façade Elevation / Cross Section /Side Elevation / Section A-A / Back Elevation

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.51-52, 53.

THEATRO DOM PEDRO V • MACAU

Plan / Façade Elevation / Cross Section /Side Elevation / Section A-A / Back Elevation

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.51-52, 53.

THEATRO DOM PEDRO V•MACAU

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.51-52, 53.

THEATRO DOM PEDRO V•MACAU

Measured drawings by the Department of Architecture, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

In: Macao Architecture, pp.51-52, 53.

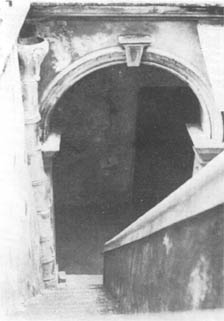

Main entrance, residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no24.

[Demolished].

The design of the main entrance is typically Chinese. The wall at the doorway is slightly recessed from the outer line of the eaves to provide a kind of porch. The eave is decorated with features in porcelain. The beam under the eave is profusely covered with carving. The top part of the wall is ornamented with panels of plaster work in bas-relief, and painted in bright colours, contrasting with the greyish fair-faced brickwork of the wall.

In: Macao Architecture, p.56-- top.

Main entrance, residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no24.

[Demolished].

The design of the main entrance is typically Chinese. The wall at the doorway is slightly recessed from the outer line of the eaves to provide a kind of porch. The eave is decorated with features in porcelain. The beam under the eave is profusely covered with carving. The top part of the wall is ornamented with panels of plaster work in bas-relief, and painted in bright colours, contrasting with the greyish fair-faced brickwork of the wall.

In: Macao Architecture, p.56-- top.

Elevation along Rua de Pedro Nolasco da Silva [Pedro Nolasco da Silva Street], residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no 24. ***

[Demolished].

Western features were incorporated in the design, such as the parapet, the windows, and the balcony. The hipped roof is hidden out of sight from the street.

Elevation along Rua de Pedro Nolasco da Silva [Pedro Nolasco da Silva Street], residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no 24. ***

[Demolished].

Western features were incorporated in the design, such as the parapet, the windows, and the balcony. The hipped roof is hidden out of sight from the street.

Rua de Pedro Nolasco da Silva (Pedro Nolasco da Silva Street)

Residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no 24 / Ground Floor Plan.

[Demolished].

Late eighteenth century. The plan follows the typical Chinese layout with the main halls in the middle and the rooms at the sides. The external wall on the ground is pierced only with widely spaced windows, guarded with heavy iron bars, thus forming an enclosure around the house. The weight of the pitched roof is carried by the masonry walls and the row of timber columns around the central court.

In: Macao Architecture, p.57.

Rua de Pedro Nolasco da Silva (Pedro Nolasco da Silva Street)

Residence at Travessa dos Anjos [Alleyway of the Angels], no 24 / Ground Floor Plan.

[Demolished].

Late eighteenth century. The plan follows the typical Chinese layout with the main halls in the middle and the rooms at the sides. The external wall on the ground is pierced only with widely spaced windows, guarded with heavy iron bars, thus forming an enclosure around the house. The weight of the pitched roof is carried by the masonry walls and the row of timber columns around the central court.

In: Macao Architecture, p.57.

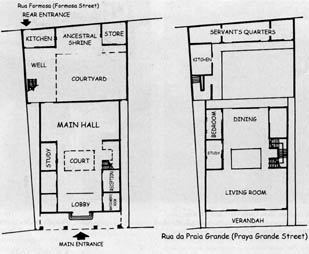

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / Front Elevation.

[Demolished].

The plan of this building [..] is typically Chinese. However, the façade with all its decorations, verandas, and the balcony is Western in design and construction. The details are painted in white with the background in a pastel shade of gree. The structure relies on load-bearing walls with columns around the courtyard, all the partition walls being structural. Timber joists in heavy sections are used for the floors.

In: Macao Architecture, p.58 -- top.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / Front Elevation.

[Demolished].

The plan of this building [..] is typically Chinese. However, the façade with all its decorations, verandas, and the balcony is Western in design and construction. The details are painted in white with the background in a pastel shade of gree. The structure relies on load-bearing walls with columns around the courtyard, all the partition walls being structural. Timber joists in heavy sections are used for the floors.

In: Macao Architecture, p.58 -- top.

Residence at Rua do Campo [Campo Street] with similar architectural characteristics.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Residence at Rua do Campo [Campo Street] with similar architectural characteristics.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street)

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / First Floor Plan.

[Demolished].

In: Macao Architecture, p.59.

Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street)

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / First Floor Plan.

[Demolished].

In: Macao Architecture, p.59.

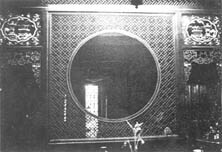

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / Interior, looking up the Courtyard from the Ground Floor.

The interior is decorated profusely with Chinese and Western features. The timber columns with the carving under the beams are of Chinese design, while the iron railing and the boarded ceiling have Western patterns. A lantern is hung over a small altar. This house is a typical example of the combination of Chinese and Portuguese architecture into a single entity. In: Macao Architecture, p.58--bottom.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 47 / Interior, looking up the Courtyard from the Ground Floor.

The interior is decorated profusely with Chinese and Western features. The timber columns with the carving under the beams are of Chinese design, while the iron railing and the boarded ceiling have Western patterns. A lantern is hung over a small altar. This house is a typical example of the combination of Chinese and Portuguese architecture into a single entity. In: Macao Architecture, p.58--bottom.

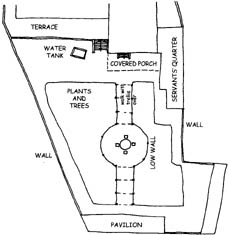

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa Avenue], no 7 / Front View.

Late nineteenth century.

This building, together with its surrounding garden is an unusual example of the combination of Chinese and Portuguese architecture.

The building itself is Western, the garden in its general layout is typically Chinese, with certain Western motifs incorporated into the design of the various features in he landscape.

The whole complex is surrounded by a wall enclosure, pierced only at the doorways. The building is painted in a pastel shade of yellow.

In: Macao Architecture, p.60 -- top.

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa Avenue], no 7 / Front View.

Late nineteenth century.

This building, together with its surrounding garden is an unusual example of the combination of Chinese and Portuguese architecture.

The building itself is Western, the garden in its general layout is typically Chinese, with certain Western motifs incorporated into the design of the various features in he landscape.

The whole complex is surrounded by a wall enclosure, pierced only at the doorways. The building is painted in a pastel shade of yellow.

In: Macao Architecture, p.60 -- top.

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa Avenue], no 7 / The Garden.

[Presently the Jardim de Lou Lim loc (Lou Lim loc Garden)].

Late nineteenth century.

The garden**** is approached through a series of gates and courts with various pavilions scattered here and there. The centre part of the garden is dominated by a large lily pond with a bridge spanning across it. As the site is flat, the principal building shown above is screened off from the garden by trees and platations.

In: Macao Architecture, p.60 -- bottom.

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa Avenue], no 7 / The Garden.

[Presently the Jardim de Lou Lim loc (Lou Lim loc Garden)].

Late nineteenth century.

The garden**** is approached through a series of gates and courts with various pavilions scattered here and there. The centre part of the garden is dominated by a large lily pond with a bridge spanning across it. As the site is flat, the principal building shown above is screened off from the garden by trees and platations.

In: Macao Architecture, p.60 -- bottom.

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa A venue], with similar architectural characteristics.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Residence at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa A venue], with similar architectural characteristics.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

The Lou Lim loc public garden.

The same gateway.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

The Lou Lim loc public garden.

The same gateway.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Public Chinese Library at Avenida de Santa Clara [St. Clare's Avenue] {sic}

[In the Jardim de São Francisco (St. Francis' Garden), near the crossroads of Rua do Campo (Campo Street) with Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street)].

Erected in the [early] twentieth century.

The plan is octagonal in shape. The construction is in reinforced concrete, with Classical motifs, topped by a Chinese tiled roof. The employment of concrete, had not, as yet, caused appreciable change in the architecture of the building. The windows and doors are painted red, in constrast with the greyish colour of the arches and piers.

In: Macao Architecture, p.61 -- top.

Public Chinese Library at Avenida de Santa Clara [St. Clare's Avenue] {sic}

[In the Jardim de São Francisco (St. Francis' Garden), near the crossroads of Rua do Campo (Campo Street) with Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street)].

Erected in the [early] twentieth century.

The plan is octagonal in shape. The construction is in reinforced concrete, with Classical motifs, topped by a Chinese tiled roof. The employment of concrete, had not, as yet, caused appreciable change in the architecture of the building. The windows and doors are painted red, in constrast with the greyish colour of the arches and piers.

In: Macao Architecture, p.61 -- top.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / The Facade.

The external appearance of the building is Western, with the veranda in front, supported by heavy brick piers, decorated with Classical motifs. The building is painted in a pastel shade of yellow with the decorative details picked out in white, a usual treatment for buildings in Macao. However, the doors at the main entrance are of Chinese design, the doorway being elevated a few steps above the street level.

In: Macao Architecture, p.62--top.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / The Facade.

The external appearance of the building is Western, with the veranda in front, supported by heavy brick piers, decorated with Classical motifs. The building is painted in a pastel shade of yellow with the decorative details picked out in white, a usual treatment for buildings in Macao. However, the doors at the main entrance are of Chinese design, the doorway being elevated a few steps above the street level.

In: Macao Architecture, p.62--top.

The Public Chinese Library.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

The Public Chinese Library.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

The Mansão Ritz [Ritz Mansion], in the Largo do Senado [Senate Square].

Built in the early days of the twentieth century. The structure is of timber and brick. Fir poles in the round are used for the floor and the roof. The pitch of the roof is cut out of sight from the street, the roof over the arcade being flat. Originally built as a hotel, the building was modified into an office building after the [Second World] War.

In: Macao Architecture, p.61 -- bottom.

The Mansão Ritz [Ritz Mansion], in the Largo do Senado [Senate Square].

Built in the early days of the twentieth century. The structure is of timber and brick. Fir poles in the round are used for the floor and the roof. The pitch of the roof is cut out of sight from the street, the roof over the arcade being flat. Originally built as a hotel, the building was modified into an office building after the [Second World] War.

In: Macao Architecture, p.61 -- bottom.

3.4. 1900-1937

The turn of the century witnessed the dwindling of both Chinese and Portuguese influences in the architecture of Macao. The International Style of modern reinforced concrete construction was slowly taking its importance. Chinese influence is still to be found in the interior decoration of the residential buildings. The design of the buildings of this period generally lacks the refinement of their predecessors. Their quality failed to keep pace with the advance of technology.

3.5. CONCLUSION

Macao architecture evolved under the mutual influences of Chinese and Portuguese architecture. The proportion of Chinese and Portuguese influences varies with the lapse of time. Thus at the beginning there were only Chinese architecture in Macao. After the coming of the Portuguese, buildings in pure Chinese architecture continued to be built. However, buildings pure Portuguese never existed. There was always some Chinese influence on certain aspects. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the majority of the buildings erected were predominantly Portuguese in character, Chinese buildings being rare and unimportant, and few survived the ages. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries witnessed the sharp decrease in number of the Portuguese buildings. The new buildings showed remarkable Chinese and Portuguese mutual influences. They form a large part of the buildings existing in Macao today, giving the special architectural character to the city. Finally, the twentieth century terminates the whole development of the mutual influences.

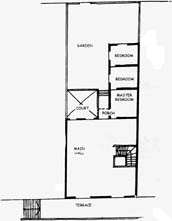

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / Ground Floor Plan/ First Floor Plan.

The general planning of the residence in Chinese, with the central courtyard reduced to the size of a lightwell, topped by a skylight. Concrete construction was employed for the floors, which rest on heavy brick piers or load bearing walls. The roof is in timberconstruction, covered with Chinese tiles.

In: Macao Architecture, p.63.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / Ground Floor Plan/ First Floor Plan.

The general planning of the residence in Chinese, with the central courtyard reduced to the size of a lightwell, topped by a skylight. Concrete construction was employed for the floors, which rest on heavy brick piers or load bearing walls. The roof is in timberconstruction, covered with Chinese tiles.

In: Macao Architecture, p.63.

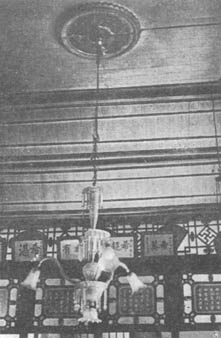

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / Interior, looking towards the lightwell.

The interior decorative work shows a strong Chinese influence in design and craftsmanship. The screen wall facing the lightwell is covered up with carving in delicate patterns, and painted gold. The ceiling is plastered with moulding of foliages at the centrte. Western motifs are often found indiscriminately intermixed with Chinese features. The introduction of reinforced concrete had not caused much change beyond the structure. [..]

The oil lamps hanging from the ceiling are meant for decorative and ceremonial purposes rather than for lighting. In: Macao Architecture, pp.62 -- bottom, 64 -- top.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / Interior, looking towards the lightwell.

The interior decorative work shows a strong Chinese influence in design and craftsmanship. The screen wall facing the lightwell is covered up with carving in delicate patterns, and painted gold. The ceiling is plastered with moulding of foliages at the centrte. Western motifs are often found indiscriminately intermixed with Chinese features. The introduction of reinforced concrete had not caused much change beyond the structure. [..]

The oil lamps hanging from the ceiling are meant for decorative and ceremonial purposes rather than for lighting. In: Macao Architecture, pp.62 -- bottom, 64 -- top.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / The Servants' Quarter.

Separated from the main part of the building by a courtyard.

Reinforced concrete is employed in the structure; however, the pitched roof on top remains in timber structure.

In: Macao Architecture, p.64 -- bottom.

Residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no 83 / The Servants' Quarter.

Separated from the main part of the building by a courtyard.

Reinforced concrete is employed in the structure; however, the pitched roof on top remains in timber structure.

In: Macao Architecture, p.64 -- bottom.

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / The Façade.

[Demolished].

The building is Western in plan and architecture. Only the arrangement of the furniture in the hall remains Chinese.

In: Macao Architecture, p.65 -- top.

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / The Façade.

[Demolished].

The building is Western in plan and architecture. Only the arrangement of the furniture in the hall remains Chinese.

In: Macao Architecture, p.65 -- top.

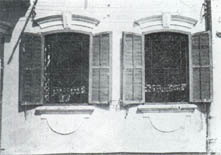

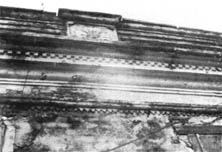

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / Side Elevation.

[Demolished].

All the windows are fitted with adjustable timber louvres, and painted brown. Chinese features are found in some parts of the building, such as rainwater pipes in the form of bamboo sections, the folding door at the main entrance, and the pitched roof over the kitchen and servants' quarter. Guangdong tiles are used at the top of the projecting cornice.

In: Macao Architecture, p.65 -- bottom.

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / Side Elevation.

[Demolished].

All the windows are fitted with adjustable timber louvres, and painted brown. Chinese features are found in some parts of the building, such as rainwater pipes in the form of bamboo sections, the folding door at the main entrance, and the pitched roof over the kitchen and servants' quarter. Guangdong tiles are used at the top of the projecting cornice.

In: Macao Architecture, p.65 -- bottom.

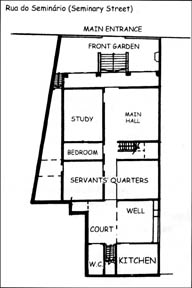

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / Ground Floor Plan.

[Demolished]. The plan is roughly divided into two parts, the living area and the service area, connected by a courtyard with a bridge at the first floor level. The rooms intercommunicate directly with one another. All the walls are structural, supporting the timber floor joists. The roof was originally pitched, covered with Chinese tiles, and supported by timber poles in the round, resting on masonry gable walls.

In: Macao Architecture, p.66.

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / Ground Floor Plan.

[Demolished]. The plan is roughly divided into two parts, the living area and the service area, connected by a courtyard with a bridge at the first floor level. The rooms intercommunicate directly with one another. All the walls are structural, supporting the timber floor joists. The roof was originally pitched, covered with Chinese tiles, and supported by timber poles in the round, resting on masonry gable walls.

In: Macao Architecture, p.66.

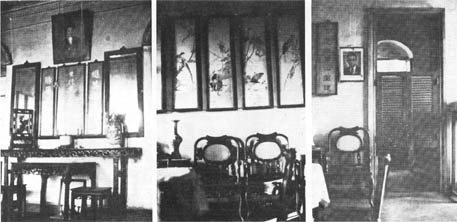

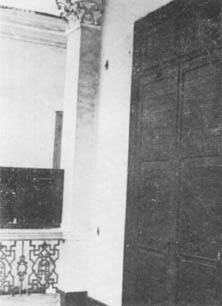

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / The Interiors.

[Demolished].

In: Macao Architecture, p.67 -- top right, bottom left and right.

Residence at Rua do Seminário [Seminary Street], nos 5-7 / The Interiors.

[Demolished].

In: Macao Architecture, p.67 -- top right, bottom left and right.

The effect of the mutual influences on the civic and religious buildings is small. It is in domes-tic buildings that Macao architecture as a special style is most distinct. In the eighteenth century residences, illustrated by the residence at Travessa dos Anjos (Alleyway of the Angels) no 24, although Portuguese ideas and features were employed, thay have been modified to the Chinese way. A century later, as found in the residence at Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street) no 47, the Portuguese features were applied as separate elements of the building. Thus the façade may be of Portuguese design, while the interior is under mixed Chinese and Portuguese influences. Compared with the residences of the previous century, the proportion of Portuguese influence had increased. By the turn of the century, the Portuguese influence further advanced in the field of interior decoration. More and more Portuguese features were employed, often found side by side with the Chinese features, as in the residence at Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street) no 83. However, the atmosphere inside the house still remained predominantly Chinese. After the First World War, Chinese influence is found only in the furniture design and arrangement, the rest of the building being Western. Decorations became simpler and less ornate, as in the residence at Rua do Seminário (Seminary Street) nos 5-7. The succeeding stage would be the gradual increase in predominance of concrete building construction, leading ultimately to the establishment of the 'International Style' in Macao.

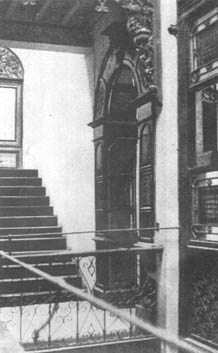

[Former] Museu Luís de Camões, [presently the Fundação Orient (Orient Foundation)].

Converted from an old residential building.

The principal floor is raised upon a storage basement, and is approached by a grand staircase, leading to an entrance porch. In front of the stair is a garden.

The rooms inside the house communicate directly with one another.

In: Macao Architecture, p.69.

[Former] Museu Luís de Camões, [presently the Fundação Orient (Orient Foundation)].

Converted from an old residential building.

The principal floor is raised upon a storage basement, and is approached by a grand staircase, leading to an entrance porch. In front of the stair is a garden.

The rooms inside the house communicate directly with one another.

In: Macao Architecture, p.69.

The Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation).

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

The Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation).

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

3.6. PLAN

3.6.1. TYPES OF PLANS

Buildings in Macao can be roughly divided into two types according to their plans, namely those with the ground used as storage and servants' quarters, and the principal living area raised to the upper floor, and those having the ground floor as principal living area. The former type is commonly found in domestic buildings in Portugal, and may be considered as introduced to Macao by the Portuguese. It is usually adopted in the older buildings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The majority of the buildings in Macao belong to the latter type.

§4. PART III -- ANALYSES OF MACAO ARCHITECTURE

4.1.

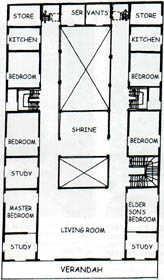

When the principal living area is on the ground floor, the plan is usually in the sequence of lobby, courtyard, main hall, service yard, kitchen and servant's quarters. In the small buildings, there is only the main hall with the rooms on either side, the kitchen being at the corner of the building.

In the multi-storied domestic buildings, the lobby is often enlarged to a front hall, which, together with the central courtyard and the main hall behind, occupies two stories in height. The bed-rooms are on the first floor, accessed from a stair by the side of the central courtyard.

In buildings of a later date, the floor height of the ground floor is increased, so that it becomes unnecessary to leave two stories for the main hall. In this way, a living-room can be afforded on the first floor, while the main hall on the ground floor is mainly devoted to ceremonies and celebrations.

Symmetry is often followed, with the central axis running through the most important halls and rooms of the building. In some locations, due to the irregularities of the site, the symmetry may be slightly modified, to take up the odd shapers of the site.

A building with similar characteristicas as the one at Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

A building with similar characteristicas as the one at Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

Late sixteenth century [residence at] Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1.

The plan takes advantage of the slope of the site to form terraces and gardens at different levels.

In: Macao Architecture, p.73 -- left.

Late sixteenth century [residence at] Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1.

The plan takes advantage of the slope of the site to form terraces and gardens at different levels.

In: Macao Architecture, p.73 -- left.

Rua de St. o António (St. Anthony's Street)

Late sixteenth century [residence at] Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1 / First Floor Plan.

In: Macao Architecture, p.73 -- right.

Rua de St. o António (St. Anthony's Street)

Late sixteenth century [residence at] Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), no 1 / First Floor Plan.

In: Macao Architecture, p.73 -- right.

Late nineteenth century residence at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13.

In: Macao Architecture, p.75 -- top.

Late nineteenth century residence at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13.

In: Macao Architecture, p.75 -- top.

A building with similar characteristicas as the one at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

A building with similar characteristicas as the one at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

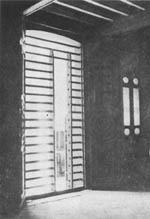

Entrance all, [residence] at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no83.

The main entrance is screened out of sight by the folding doors, which gives privacy on ordinary days, and can be completely removed on great occasions.

Entrance all, [residence] at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street], no83.

The main entrance is screened out of sight by the folding doors, which gives privacy on ordinary days, and can be completely removed on great occasions.

Residence at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13 / Ground Floor Plan.

In: Macao Architecture, p.75 -- bottom left.

Residence at Avenida do Coronel Mesquita [Colonel Mesquita Avenue], no13 / Ground Floor Plan.

In: Macao Architecture, p.75 -- bottom left.

Residence at Travessa da Sé [Alleway of the Cathedral], no3 /Ground Floor Plan.

The layout is typically Chinese. In: Macao Architecture, p.76 -- top.

Residence at Travessa da Sé [Alleway of the Cathedral], no3 /Ground Floor Plan.

The layout is typically Chinese. In: Macao Architecture, p.76 -- top.

Residence at Travessa da Sé [Alleyway of the Cathedral], no3.

In: Macao Architecture, p.76 -- bottom.

Residence at Travessa da Sé [Alleyway of the Cathedral], no3.

In: Macao Architecture, p.76 -- bottom.

The ancestral shrine is found in almost every house of the Chinese. In the smaller buildings, an altar, instead of a room, is substituted. It is located on the central axis, often at the end of it.

The same residence.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

The same residence.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

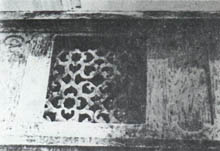

4.1.1. BASEMENT

The basement is one of the many Western ideas and features introduced to Macao. It is never used in Chinese architecture, but is very common with Portuguese architecture. It provides additional space for storage. Sometimes, it is found largely underground with only the windows above the level of the street. In such cases, it is usually poor ventilated, dark and damp inside, especially when the problem of damp-proofing has not been well considered. Sometimes, the basement is entirely above ground, with the first floor as the principal floor. When thus built, the kitchen and service areas are incorporated in the basement. The windows of the basement are widely spaced and protected with heavy iron bars for security.

A central courtyard in Seminário de São José [St. Joseph's Seminary].

At the centre of the courtyard is a well.

In: Macao Architecture, p.77.

A central courtyard in Seminário de São José [St. Joseph's Seminary].

At the centre of the courtyard is a well.

In: Macao Architecture, p.77.

The same courtyard.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

The same courtyard.

Photograph taken in 1988, by Joaquim de Castro.

4.1.2. COURTYARD

The courtyard is common to both Chinese and Portuguese architecture, and is favourably employed in domestic buildings in Macao. Due to the crampness of space, it is often reduced to a lightwell for admitting light to the interior space rather than an area for outdoor living. When used as a service yard, it separates the kitchen and servants' quarters from the main part of the building.

4.1.3. VERANDAHS

The verandahs found in buildings in Macao are generally of Western design and construction. They are usually built in front of the house or around the courtyard. They offer shelter from the sun and rain, and provide a space for living intermediate between indoor and outdoor.

The weight of the verandan is supported by the wall of the building and the row of piers or columns on the exposed side. Before the introduction of concrete in Macao, the space between the columns or piers is spanned by arches, or by a stone slab when the span is small. The arches and piers are built in brick and decorated with classical motifs. The roof of the verandahs is flat with a parapet at the sides. The doors opening into the verandah are usually 'French doors'.

It is not uncommon to find a building in Macao where the verandah is in Western style while the rest of the building is predominantly Chinese.

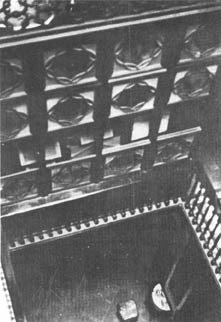

A lightwell in a multi-storied residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street]. no83.

Behind the lightwell is the main hall. On the side of the lightwell is the staircase, and on the other the study.

In: Macao Architecture, p.78 -- top.

A lightwell in a multi-storied residence at Rua da Praia Grande [Praya Grande Street]. no83.

Behind the lightwell is the main hall. On the side of the lightwell is the staircase, and on the other the study.

In: Macao Architecture, p.78 -- top.

Verandah of the Centro de Saude [Health Centre], [at Rua do Campo [Campo Street].

Most of the verandas found in Macao are of great width. In: Macao Architecture, p.79.

Verandah of the Centro de Saude [Health Centre], [at Rua do Campo [Campo Street].

Most of the verandas found in Macao are of great width. In: Macao Architecture, p.79.

Residence at Rua do Campo [Street of the Good Delivery].

[Demolished]. Here, the principal courtyard is found in front of the houses, defined by the wall enclosure on the street front. The courtyard, planted with trees and flowers, serves as an outdoor living room, while enjoying maximum privacy.

In: Macao Architecture, p.78 -- bottom.

Residence at Rua do Campo [Street of the Good Delivery].

[Demolished]. Here, the principal courtyard is found in front of the houses, defined by the wall enclosure on the street front. The courtyard, planted with trees and flowers, serves as an outdoor living room, while enjoying maximum privacy.

In: Macao Architecture, p.78 -- bottom.

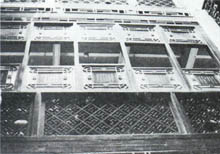

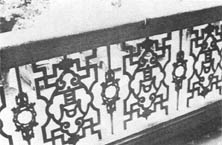

4.1.4. BALCONIES

The projecting balcony is a typical Baroque feature commonly found in Macao. It gives a relief to the monotony of the façade and adds special architectural life to the town houses. It offers some shelter from the weather as well as a space for viewing and for the growing of plants on the upper floors high above the ground level.

The balcony is usually carried on brackets projecting from the external wall of the building. Vertical supports are in the form of slender columns of cast iron or stone. The central part of the projecting platform often protrudes in the form of a segmental bulge, thus giving a curved line of the façade of the building. When found in a row of houses, this curved line presents an undulating movement to the street frontage. The railing is of fine ironmongery work in various graceful patterns, sometimes Chinese, sometimes Portuguese.

4.2. CONSTRUCTION

4.2.1. STRUCTURE

The structure of the majority of the buildings in Macao consists of load-bearing walls, supporting the floor and the roof. The structural wall is generally preferred to the framed construction. As most of the buildings in Macao are multistoried, there is the problem of withstanding the typhoons. In this respect, the structural wall offers a better solution than the framed structure, when only timber, brick and stone are the materials available. The framed structure in timber, so common in Chinese architecture, is rarely found in Macao.

The space between the load-bearing walls is spanned with timber joists at close intervals. The length of timber available limits the position of the walls. In the large halls, primary beams in heavy sections are introduced to support the floor, thus reducing the span of the joists. In the case of the roof, trusses are the substitute. For short spans, the floor joists are usually on round poles.

Balconies of residencial buildings at Rua de São Paulo [St. Paul's Street], nos24-28.

Note the doors at the main entrance on the ground floor are of Chinese design while the door head and window heads, of the upper floors are decorated with classical motifs. The delicacy of the elements of the balconies gives a feeling of lightness, flowing above ground.

In: Macao Architecture, p.80.

4.2.2. FOUNDATION

The foundation is usually carried above ground level, sometimes up to 0.90 or 1.20 metres. Stone is the most common material employed. When rough rubbles are used, they are stuccoed on the exposed surface to conceal the irregularities. More often, the stone work is faced with ashlar, pointed with fine cement.

On sloping sites, the foundation often forms the wall of the basement, which is partly above and partly below the level of the street outside. In such a case, the foundation also acts as a retaining wall.

The same buildings' balconies.

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro. In free-standing garden buildings, the foundation is sometimes found in a low podium, on which stands the structure of the building.

4.2.3. WALLS

Walls are thick and strongly built, as they are intended for structural purposes. The thickness of the wall also helps to provide thermal insulation. Cavity construction is common having 22.5 cm brickwork for each leave.

The early buildings in Macao have chunambo (a peculiar mixture of earth, straw a lime, well pounded together with oyster-shells) for their walls. The walls thus formed are thick and strong. When plastered on the outside, they are very durable. Most of the fortresses and city walls constructed in the early days are of this material.

Seminário de São José [St. Joseph's Seminary].

Photograph taken in 1998, by Joaquim de Castro.

Seminário de São José [St. Joseph's Seminary].

Note the use of different materials, with stone for the base of the thick loadbearing wall, and the brick for the upper portion, which is stuccoed.

In: Macao Architecture, p.83.

Bricks are the principal building materials used. Extremely hard and durable bricks are obtained from the Southern area of China; they are well baked, have a crisp, metallic ring when struck together and are composed of fine greyish-blue clay. They are baked in charcoal kilns and sometimes have the stamps of the brickmaker upon then. When an old part of the Seminário de São José (St. Joseph's Seminary) was pulled down, some bricks were tested at the University of Hong Kong, and although almost three-hundred years old, they still proved to be better than the London Stocks or Flettons. They are large size bricks, measuring 33.6 x 10.8 x 7.2 cm. Pale brown bricks, produced by sun-drying, are rarely used.

Timber column in [the pavilion of the residence] at Avenida de Horta e Costa [Horta e Costa Avenue], no7.

[Demolished]

The whole building is raised above ground level with a foundation of stone. The timber columns are tied up at the top with wooden beams. At the lower end the stone pedestal prevents the timber from dampness, coming from the ground.

In: Macao Architecture, p.84.