Affairs were not running smoothly in the Middle Kingdom - a bad sign for the merchants in Macau. Manuel de Saldanha, an experienced diplomat, was sent to Peking to secure from Emperor Kang-Si personal guarantees of stability and trading rights in China. By the time Saldanha passed away, just after completing his dangerous mission, the Emperor had been so deeply impressed by him that he ordered a burial with honours fit for the finest mandarins of his empire.

Over the period lasting from 1368 to 1644, China was experiencing one of her most dazzling periods in history. Ming, meaning 'brilliant' or 'glorious' was the title given to the ruling dynasty.

Emperor Chu Yuan-Chang had founded the dynasty but it was to reach its peak under Emperor Yung-le who reigned from 1402 to 1424. Politics, diplomatic relations and art all contributed to increasing the stature of the Middle Kingdom. China expanded her borders; there were visits to far-off lands from Aman to Arabia and the coast of Somalia; Pe-king, the new capital city, was given a face-lift; porcelain1, jade and ivory craftsmanship had never been surpassed in beauty, form and colour; the monumental work, Yung-le ta-tien was compiled to serve as a record and source for studying Chinese literature; the Grand Canal was opened allowing easy provisioning for Peking; there was increasing adherence to Confucianism and deeper study of classical texts even though the Emperor was more inclined to Tibetan Buddhism. Latourette2 summarizes the situation as follows: Under him the Ming dynasty reached the apex of its power. He vigorously maintained and extended Chinese prestige abroad and gave the Empire an energetic administration.

But the peak always passes quickly and great civilisations quickly begin to weaken the talents of those who have put so much effort and ambition into rising ever higher.

The golden age of Yung-le was followed by rapid decline with the dark days of the reign of Wanli. 3 The eunuchs and concubines had gained control of the empire despite protest from the scholars who foresaw the impending disaster. Taking advantage of the ruler's weakened power, the Japanese attacked the coasts of China once more and even went so far as to invade Korea with the notion, masterminded by the shogun Hideyoshi, that they would conquer the entire Empire. Days of hunger followed: the gods had abandoned the reign of Wan-li. No seed was sown in the fields, no rice grew... and the threatening, terrifying hordes of Manchus began to come down from the northeast

Macau was the training ground for missionaries. Here was where they prepared for the challenge of teaching and converting the Chinese. Here was where they set sail on the holy crusade which was also Portugal's crusade. All means were employed in trying to break through the impenetrable barrier surrounding China.

A famous Chinese scholar and statesman who had been converted by Ricci -- Paulo Hsu Kuang-Ch'i - suggested to the Portuguese that they should offer their military services to the ailing dynasty under attack from the Tartar Manchus. The province of Macau could already boast a flourishing weaponry foundry directed by Manuel Tavares Bocarro. 4 The idea of supplying Peking with cannons, along with a few Jesuits who would go along to instruct the Chinese on their proper use, was supported by some mandarins such as Li Chih-tsao, president of the Council of Rites in Nanking. 5

Confronted by the Jesuits' reluctance to become so directly involved in the war, Li produced the following apology: Fathers, let this not disturb you for the military plan will serve our requirements no more that the needle serves those of the tailor for, when he has secured the thread and prepared the garment, he sets aside the needle. Should your Very Reverends become involved on the king's orders, the weapons shall be transformed into quills. Consequently, the first cannons bearing the Portuguese coat-of-arms left Macau to be used by the Ming troops.

A few years later, in 1629, as the Manchu troops were coming frighteningly close to Peking, Emperor Ch'ung Cheng decided to ask the Jesuits for renewed help from the Portuguese. The Loyal Senate of Macau immediately used this opportunity to organize a splendid display of military force. There were certainly major material benefits for the Portuguese in this action but the advantages to be reaped in winning greater prestige and security for the Portuguese in Macau and enabling missionaries to enter China were even more significant and more valuable.

Father Semedo explains how the forces were organized before undertaking this trial:

Four hundred men were prepared: two hundred of these were soldiers of whom many were Portuguese, some born in Portugal and others born there (in Macau) but the greater part was composed of locals born in Macau and educated according to Portuguese customs and these were good soldiers with a fine aim.

Each soldier was appointed a boy to serve him, bought with the King's money. There was so much money left over that the soldiers were able to buy their weapons, dress themselves in the richest finery and still call themselves rich.

These soldiers left Macau under two captains, one called Pedro Cordeiro and the other António Rodrigues del Campo with their lieutenants and other officers. When they arrived in Canton, they were so finely turned out and let off so many gun-salutes that the Chinese were amazed.

There they were provided with boats to go up the river in comfort and throughout the province, whenever they arrived in some city or village, the local magistrate presented them with chickens, meat, fruit, wine, rice and so on.

All of them, even the most lowly servant, rode across the mountains separating the Province of Canton from that of Kiangsi (less than one day's travel from the other river). Once they had reached the other side of the mountains, they embarked once again and sailed downstream across almost all Kiangsi until they arrived at the provincial capital, Nanchang, where I was living at the time and had a large number of Christians under my care. Here they stopped to see the city and pick up provisions. They were invited by many of the nobles to admire their customs and many other unusual things. These noblemen lavished praise on everything except for the holes and seams in the clothes for they could not understand how there could be men who would cut a piece of new cloth just for decoration. 6

In the end, this auspicious start to proceedings was not to last long. Rivalries between Canton and Peking caused the expedition to fail although the Emperor was still to bestow honours on some of the members.

Canton feared that any victory on the part of the Portuguese would lead the Emperor to ordain the opening of the ports to Portuguese trade. Until now, the capital of Kwangtung Province had been the only link with Macau and was thus a ripe source of income for some high-ranking officials.

In 1643, in the last stages of the Ming, the Viceroy of Kwangtung and Kwansi ordered a large iron cannon to be sent from Macau to protect the city of Canton while three artillerymen were to be sent to Nanking. Payment for this service came shortly after in the form of ceding a small strip of Lappa Island to the Jesuits. 7

Although China had now fallen under the almost complete control of the Tartars, Macau lost no time in helping Emperor Yung-li who was resisting in Kwangtung and Kwangsi Provinces The defence of Kweilin by this courageous ruler of the fallen dynasty was, in large part, due to the efforts of three hundred members of the Portuguese troops. Nevertheless, this expedition is surrounded in mystery and there are those who doubt whether it ever existed at all. 8

However much Macau wished to help, the Ming had been soundly defeated and the Manchu banners were raised over Peking and the rest of China.

The life and deeds of the pirate Kuo-hsing-yeh (Coxinga) could almost read as one of the great Chinese legends were it not that the facts can be historically proven. 9

Coxinga, the pirate, fought against the powerful, war-mongering Manchu dynasty in its early years on the basis that China should belong to the Chinese. The son of a Chinese father and Japanese mother, Coxinga was an intrepid sailor who attacked the foreign-controlled coastal areas of his country. He expelled the Dutch from Formosa and swearing that he would take revenge on the death of his father and two brothers who had been executed by the Manchus he set off in the name of his own family and the Chinese nation to plunder and attack the hated invaders.

The scholarly introduction to the "Diário do Padre Luís da Gama"10 notes that: if his life had not been cut short so abruptly in the midst of his victories, he would have certainly managed to place the Tartars, at that point lords of almost all of China, in a precarious position.

Confronted with Coxinga's repeated attacks in the south, the Regents acting on behalf of Emperor K'ang-hsi until he reached his majority ordered that the coastal villages should be evacuated to the interior so that the pirate would not be able to find provisions so easily. This decree, issued on the eighth moon of 1661, expressly forbade maritime trade in the coastal cities. Hard times were ahead for the City of the Name of God.

In his Historie de la Chine sous la Domination de les Tartares11, Adriano Greston gives a clear explanation of the Portuguese situation:

It is important to remember that Macau is located on a peninsula of no more than one league in circumference where there is no agricultural land except for a few market gardens which produce some vegetables, meaning that all essentials must be imported from China to which Macau is connected by a narrow strip of land in the middle of which stands a high wall with gates to mark the division. This gate was opened every day prior to the prohibition on trade and the villagers from the neighbouring areas were free to go to Macau to sell their merchandise. The Portuguese thus lacked for nothing, but the Tartars wanted to push the Portuguese out of this port and into China for they cannot abide there being foreigners living on the borders of their country and in possession of forts and artillery. And so they organized a border guard to guard the wall with orders only to open the gate on certain days. It was opened once a month, and after this persecution began it was taken to such lengths that sometimes months would pass without it being opened.

This constant threat to push the Portuguese out of Macau now weighed heavily on them. To avoid this situation, the Portuguese negotiated and bribed when physical and mental misery was hitting hardest. The diary of the Jesuit Luís da Gama gives a vivid account of those luckless times. The names of those who laid the foundations for the defense of Macau with their miserable dealings cannot be included in Portugal's heroic history. There is certainly an explanation for what happened, however: Macau, abandoned at such a distance from the motherland, was using all possible means to save herself from this hell.

In the Relação (report) of Saldanha's mission to the Emperor of China12, Father Francisco Pimentel wrote:

The prohibition on trading with Macau arrived in 1662. In it, the Emperor ordered that not a single plank of wood from his Empire should float on the seas and that there should be no trade with foreigners on pain of death. As the inhabitants of this city had no basic goods nor any land to bury their dead, denying them trade was equivalent to denying them life. During the first few years, they survived on the goods they had stocked up in the hope that the Emperor, seeing that the fattened hog continued to flourish, and that his own vassals were suffering, would realise that his decree was not hurting his enemies but rather his own subjects and would therefore lift the prohibition. All the same, given the tyrant he was, in his fear of losing the Empire which he himself had usurped, he continued to order strict adherence to his dreadful decree until, in November 166713, the people of Macau decided to send an urgent request to the Viceroy of India, Count Sao Vicente Joao Nunes da Cunha asking him to send an Ambassador in the name of Our Majesty so that he could go to the Court and tell the Emperor of the terrible state of affairs in the city and allow them enough trade to survive. Only this path offered hope of finding a solution to their ills. The only person the Viceroy could find to take on such an arduous task was Manuel de Saldanha who, motivated more by faith which in this region depends principally on the conservation of this city and the support of Our Lord the King, than by any other reason, set off for Goa as soon as he had recovered from a long illness. After having encountered the most dreadful dangers on the way, from which he escaped by pure miracle, he arrived in this City suffering from illness on the 4th day of August. Although sick, he immediately set off for Canton City, Capital of this Province where the Governors held him for over two years for reasons which I shall tell later, until finally an order came from the Emperor to release him without further delay to travel on to the Court. 14

Little is known about the Portuguese Ambassador's life. According to Father Domingos de Navarrete in his Tratados15, Saldanha had taken part in the Conde da Torre's ill-fated expedition to Brazil in 1638. The Portuguese fleet had been defeated by the Dutch near to Pernambuco. Saldanha also fought in the Restoration as a captain of cavalry and it was he who had been in charge of the battalion when it was attacked by the Duque de San Germain in 1657. Manuel de Saldanha left for India in disgrace, hardly up to the responsibilities of the position which had been given to him. In his acceptance of the risky, important task of going on the mission, there may have been some hope of making up for past mistakes.

The dates of the Chinese document Chinese Relations with Foreign Countries do not coincide with those provided by Father Pimentel although the error may arise from calculations made on the Chinese calendar. The Chinese document claims that Saldanha stayed in Macau for a year but probably the Breve Relação written on the voyage is nearer to the truth. The Ambassador must have set sail from Macau for Canton not immediately, as Pimentel says, but rather three and a half months later (from a document in the Leal Senado) although he was still ill. On the list of expenditures relating to Saldanha's stay in Macau16, there is mention of: Ambassador Manvel de Saldanha, who arrived in this City from India on the 6th of August, 1667, and left for Canton on the twenty first of November of the same year...

The date of arrival given here does not coincide with that provided by Pimentel in his Relação but there is only a difference of two days.

Montalto de Jesus17 must have based his findings on the document in the Leal Senado in his description of the Ambadassor's committee and the presents he took from Canton to Peking, all paid for by the City of the Name of God.

Diplomatic missions to the Middle Kingdom had to be accompanied by every pomp and circumstance. The sacrifices made by the leaders of these missions were frequently great as they had to wear outfits made of brocade and heavy velvet and on top of those cloaks, none of which helped to combat the humid, stuffy, depressing and exhausting climate.

To the Chinese, the grandeur of the expeditions and the brilliance of their apparel emphasised the mission of these 'foreign devils' even though they were still regarded as tributaries of the Emperor.

Accompanying Manuel de Saldanha was the aytão, which Monsignor Sebastião Rodolfo Delgado18 indicates was the title of the Chinese admiral. 19

The chaplain to the group was Father Simão da Graça from the Church of Santo Agostinho; Bento Pereira de Faria "citizen and resident in this city" served as the secretary. 20 Vasco Barbosa de Melo, also a Macanese, "went to advise them about doing business with the Chinese for he has much experience of this".

There follows a report on the other positions held by members of the entourage. The Leal Senado document reads: Domingos da Silveira, as the Secretary's first assistant. Another official for the same Secretary who can write Chinese. Twelve gentlemen to lend greater authority, all of these being respectable men, some of them members of the gentry. Seven pages to serve the Ambassador. A company of twenty riflemen with their Captain. Two valets, a butler, a chamberlain, two footmen, and two Chinese-speaking interpreters, two pharmacists, two trumpeters, one drummer, a surgeon, two washermen and two carpenters.

The presents taken for the high officials of Canton and for the Emperor fill pages of the manuscript: golden swords set with jewels, cabinets, coral, silver snuff boxes, miniature portraits of the King in gold and ivory, rugs, ornamental chains, elephant tusks, incense, exquisite wines from Portugal, oil of benjamin and cloves, mirrors, chints and robes. In other words, unlimited wealth meant to dazzle the Orient and open the doors to the Portuguese Ambassador. 21

Although Saldanha was seriously ill, he must have found the journey up the Western River interesting, passing through channels cut low out of the marshlands where rice was grown. Men and women balanced heavy loads on the bamboo poles they carried on their shoulders as they passed so close to the junks which slowly made their way up the channels with their membranous sails turning golden in the sunset like banana leaves in Autumn. From the boat one could hear the conversations and laments of those who were passing by.

Later, the entourage arrived in Canton with its sampans decked in flowers and banners, with, in the distance, the long, low lines of sandy-coloured mournful houses where Chinese characters stood out in stunning shades of ink. Saldanha's heart must have filled with longing for far-off sunny Portugal when he looked out at the countryside enveloped in damp like the tentacles of an octopus strangling the souls of the Westerners. Not even the splendid blood-red sunsets tinged with gold and purple could have made up for the views of the sun setting into the Atlantic from the beaches of his motherland. In contact with the Chinese land, his body must have gathered strength in the atmosphere perfumed with the sweet scent of incense and joss-sticks which smouldered in honour of the gods. He must have felt lulled by the guttural chants, by the strange music with strings vibrating in sighs not of revolt but of anguish... Saldanha found enough strength to confront the dangers of the long journey to Peking combined with enough patience to spend two years negotiating his entry into the Forbidden City.

The Ambassador left this City of Canton on the 4th of January, 167022 with all the state and splendour fitting to his person and position. He was dressed in crimson satin with the brim of his hat and chain all decorated with silver. The entire room was covered in carpets which are held in high esteem in China. There was a bolt of red damask fringed with gold beneath which was carried the letter of introduction and the protrait of Our Lord the King, two benches covered with cloths of the same damask, eight chairs padded with red velvet with golden fringes and six flat velvet chairs with fringes at the edges and at the door to the hall, a damask curtain fringed with gold and silk.

The crowds thronged at the quayside to witness the departure of the Embassy. The Viceroy of Canton and the titó23,as the commander of the provincial troops was called, ordered the windows of the palaces to be opened so that even though there were curtains hanging to preserve their dignity, the people should be able to admire the splendour of the barbarian on his way to the imperial court.

The Ambassador did not take all his entourage from Macau with him as he was only allowed twelve Portuguese men to accompany him.

Father Pimentel describes the procession in his Breve Relação:

A boat bearing the banner and coat-of-arms of the King went ahead and in this way they crossed the whole of this great Empire until they reached Peking. They also took a yellow banner of the kind used in China bearing characters which the fathers had given us and which said: "This is the Ambassador of His Majesty, the King of Portugal who has come to congratulate the Emperor of China ".

The Jesuit adds. that:

Succeeding in not having to put the word 'Cimcum' which means 'tributary' on the banner wasthe greatest victory which the Ambassador could have achieved for in doing so he broke with a tradition which has existed in this Empire for over two thousand years and which has meant that no ambassador has been received unless as a tributary.

Indeed, it was not so long since the Dutch ambassador, who had visited in 1656, had been obliged to tolerate this humiliating treatment. 24

The Embassy was warmly welcomed along the way. In the narrow canals crammed with sampans and junks, the floating cities cleared a path for the Ambassador from the "great kingdom of the Western sea". Even when there was a problem with protocol such as that which occurred with the boat of the Regulator of Fukien Province when they were already in Peking Province, and which refused to make way without consulting the court first, a timely storm erupted, thus resolving the tension by opening the way to Manuel de Saldanha's great junk.

The journey was extremely difficult for the ambassador who was increasingly victim to ill health. Four leagues from the capital city, the fathers from the Portuguese Mission came to visit him "and instruct him in the necessary business ahead".25

Three days later, on the last day of June, Saldanha entered Peking in the company of a Mandarin sent from the Tribunal of Rites. The enervating days of waiting that followed were occupied with the complex steps required by the imperial ceremonies. First, the Ambassador handed over his letter of introduction and a portrait of D. Afonso VI to the Tribunal of Rites. Then came the questions: why did the royal document not include the word meaning 'vassal'? The ambassador immediately replied that in Europe it was neither the style nor the custom when Kings wrote to one another for them to treat each other as vassals. 26 This was one of the most sensitive issues of the entire mission. The yellow banner used on the junk which brought Saldanha to the capital had omitted the word 'cimcum' composed of two characters, the first meaning 'to enter' and the second meaning 'tribute'. The humiliating word had been changed by the Jesuits without any protest from the Chinese authorities and replaced with the word 'ho' meaning 'congratulations'.

The members of the Tribunal of Rites also wanted to know whether the King of Portugal was intending to send another embassy to China, to which Saldanha replied that he did not know.

As the ambassador's state of health was deteriorating, the Emperor immediately sent two of his own physicians and requested to be kept informed as to his condition. Father Pimentel mentions the fact: Never since ancient times, had the Emperor bestowed such favours and honours on anyone as those he gave to the Ambassador. 27

It was only on the 30th of July that Saldanha was well enough to go with his entourage to the Tribunal to learn the rituals customary at imperial audiences. They learnt how to kneel, how to kowtow touching the brim of their hat on the floor (and never letting their hat fall off, for the Chinese regarded this as "the most rustic, discourteous gesture of all"). 28 They also politely advised the ambassador not to take his sword to the audience with the Emperor, advice which Saldanha chose to ignore. New meetings were held because of this refusal and finally, out of great consideration and benevolence, his opinion was accommodated. 29

Let us now turn to Father Pimentel's description of Saldanha's audience with the Lord of China, Son of Heaven.

The 31st was the first occasion on which he [the Ambassador] entered the palace, dressed in black camel-hair from Persia. This was a novelty for the Chinese as it was not silk, and because of this it was greatly valued. The decoration on his hat, scabard, shoulder-belt and chain of office was all of silver. The chair in which he was carried was slightly smaller than a sedan-chair and had no cover for its cover was made of red gold with golden gauze curtains and the Mandarins said that he could not go to the palace with it as those were the colours of the Emperor and nobody could use them but he. The Ambassador had another cover which was even richer encrusted with pearls and diamonds and as it did not have the colours of the Emperor, he could use it. Later, we checked if what we had been told was really true and indeed everything belonging to the Emperor is made of those colours. Even the roof tiles are glazed in red and yellow. Male relatives closest to the emperor may wear a yellow sash while those who are more distant and female relatives wear red sashes.

Once the Ambassador had arrived at the Palace, we paid the customary respects to the Emperor in the courtyard where over five thousand Mandarins also paid their respects, for only they can enter this part. These rituals are accompanied by various instruments which are played in a room which leads onto the courtyard from the Throne Room.

The signal for the courtesies to begin consists of eight cracks of whips which are like coachmen's whips except incomparably bigger. They are so heavy they can hardly be lifted from the ground and when cracked make a sound like eight pistol shots. There is always a Mandarin to make sure that nobody makes a mistake or disturbs the ritual. He calls out when one must kneel, kowtow, stand up and so on so that everybody performs the same action at the same time. The imperial chamber is very large and decorated throughout in gold, red and blue. There are seventy columns in two files which divide the chamber into three naves as in our churches. From the courtyard, one goes up five flights of steps as white as marble and delicately carved. In the centre are two landings with handrails of the same stone which are of the greatest perfection. In the spaces between the steps there are spherical, polished bronze incense burners of an immense size. On the final landing where the steps come to an end there is the imperial chamber running the length of the landing.

This chamber has three doors opening off the landing. In front of the main door is the imperial throne, standing almost six yards high and made of exquisitely carved wood. The place where the Emperor sits has no footstool nor canopy, nor even a backrest but it is fashioned like a table with two superstitious motifs [dragons] from this Empire between whose tails the Emperor sits with his legs crossed. There was no backrest for as we looked up from the courtyard where we paid our respects to him we saw him as he sat, from the waist up and behind him the light and air came in through the door opposite the front entrance. I am describing this in such detail because it is very difficult to gain an idea of a building through the written word...

The Jesuit did well to provide such a detailed description of the Palace in Peking and the elaborateness of the ceremony with which the Ambassador was received, even though his style was somewhat dry.

Following the lengthy ritual, the Emperor requested Saldanha to approach and spoke to him in affable, respectful terms. He offered the Ambassador tea and treated him as a great vassal of the King of Portugal. The Emperor in question was Kang Hsi, a culturally aware sovereign who was interested in the West. The Jesuit Verbiest, who had taken over from Ricci and Schall in influencing the court, held an important position close to Kang Hsi. Because Verbiest worked in the Portuguese Mission, he was able to promote the spiritual interests of the Portuguese.

Kang Hsi, regarded by many as a more talented monarch than contemporaries such as Louis XIV of France and Peter the Great of Russia, requested that the Ambassador return on the same morning as the official ceremonies had taken place.

The fresh talks took place in an atmosphere of general surprise at such an unusual favour being bestowed on the Ambassador. They talked on a balcony near the ladies' chambers where no man could enter but the eunuchs. Father Verbiest was the interpreter aided by another Jesuit, Father Buglio.

Nobody else was present at the interview but we can assume that it was a friendly exchange. At the end, the Emperor gave the Portuguese diplomat and his retinue a gift. The event in itself, however, was so unusual that it deserves to be remembered in both the East and the West. One of the most outstanding Emperors of China, whose life and work have been recorded throughout the world, a Jesuit admired for his wisdom and culture representing Western science, and an ambassador of the country which had led the great nations of Europe by the hand to an understanding and respect for the Middle Kingdom: a group which symbolises Portuguese spiritual and cultural work in China.

While the Ambassador was a guest of the Court, the Emperor broke the customs of his country to promote Verbiest to the post of President of the Mathematics Tribunal. The isolated kingdom was beginning to allow the Portuguese Missions to open gaps in its ancient walls. The priests' education, tact and powers of persuasion eliminated barriers which had long stood as a challenge to men's time and strength. The men who went to China preaching the word of Christ, who wanted to reveal the spiritual riches of European civilisation, also carried the greatness of the far-off country which had sent them there alongside the brave discoverers. The missionary work led to increased prestige for Portugal in Cathay's proud domain.

Banquets followed in the style of the Manchus: the Portuguese hardly touched the blood-rare beef, pork, horse, buffalo and chickens. The Breve Relação does not mention the strong wines of northern China but these meals would almost certainly have been accompanied by copious quantities of alcohol in the custom of the East.

The Ambassador had a second interview with the Emperor shortly afterwards. It took place in the court where this time the intricacies of the ritual were prepared in such a way to allow the imperial concubines to catch a glimpse of the visiting barbarians. More accustomed to the ugliness of the Tartars, we can imagine the comments and barely-disguised laughs emanating from the delicate, voluptuous, dainty-footed ladies, swathed in the silken tunics which lent grace to their posture. The ever-alert Jesuit was not unaware of the modifications which had been made to the usual protocol.

Now was the time for the Portuguese Ambassador to broach the real purpose of his demanding mission. He had brought from Macau a document stating the services which had been rendered by the Portuguese to the Emperor in the matters of expelling the Dutch and bringing to an end piracy as well as other acts of great bravery. The mission fathers had told him from the outset that it would be foolhardy to submit this document to the Emperor.

When he was asked in Canton about the motive behind the mission, Saldanha had said that it was in order to congratulate Emperor Kang Hsi. It would be very unwise for him to now display quite openly the real reason for his visit. If he were to take out the scrolls in the presence of the Manchus, it would merely contribute to an atmosphere of mistrust and fear. The Dutch had set a precedent for this kind of behaviour which Father Pimentel describes as follows:

The Tartars had given them two hongs, one in Nanking and the other in Fukien on condition that they helped the Tartars get rid of the long-haired Chinamen who were still occupying some islands near Chicheo [sic] Province. They accepted the challenge and arrived with fourteen ships and the military skill and courage for which they are so famous and respected. Nevertheless, on this occasion as they had the Tartars there, whose friendship they had sought so hard, they fought harder than ever and although they lost three ships they defeated the enemy and captured the islands which the Tartars immediately took over. But who would credit that by doing so they lost China forever: where they deserved respect and esteem they earned the hate of all. The Fathers said that the Tartars returned from the war with their fingers in their mouths as a sign of their great fear and went through the streets shouting "Take care, take care, people who fight like this must leave". In other words, they had taken a snake to their breast, brought the tiger into their home. So that wherever the Dutch wished to make friends they were regarded as formidable and dreadful and were immediately treated badly. Not only were they not given the promised hongs, they were thrown out with a thousand insults and humiliations. Now, people from Macau, think of whether it would be useful to allege the use of weapons and courage when the Tartars here in the court live in fear of the artillery stationed in Macau and often speak of it. 30

The Jesuit was referring to the Dutch expedition which had fought under the command of Admiral Barthasar Bort against Koxinga's supporters. The missionaries' warning was prudent and Saldanha lost no time in following it. In what was to be the final interview he had with Kang-Hsi, he continued to put forward the difficulties encountered by Macau. He hardly need have worried. The Emperor had been briefed by the Jesuits and replied that he already knew everything.

Would it have been possible to broach this sensitive subject with more tact? I think not. The Ambassador was wise enough to listen to both those who were familiar with the setting and also those who understood Portugal's interests and who were close to the Emperor. Saldanha displayed his exceptional gifts as a diplomat to achieve the objectives of the mission without grasping the honours to himself. He coordinated various efforts and tried to understand the environment in which he had to move.

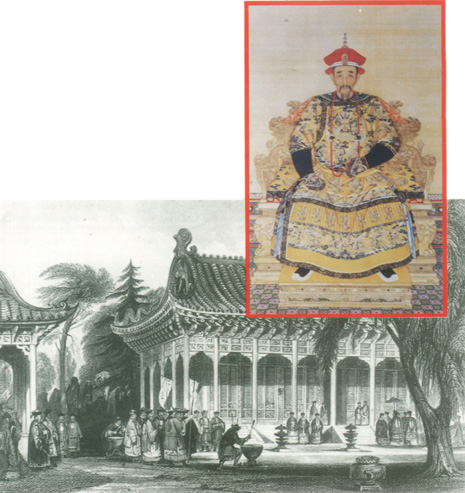

Above: a portrait of Emperor Kang-Hsi. Below: a pavilion of the former Summer Palace, ordered by Emperor Kang-Hsi as shown in a nineteenth-century engraving. The palace was destroyed by French and British troops in the 1860 occupation of Peking. This building was generally used for receiving foreign ambassadors during their visits to the imperial court and we can assume that Saldanha would have been received in similar surroundings.

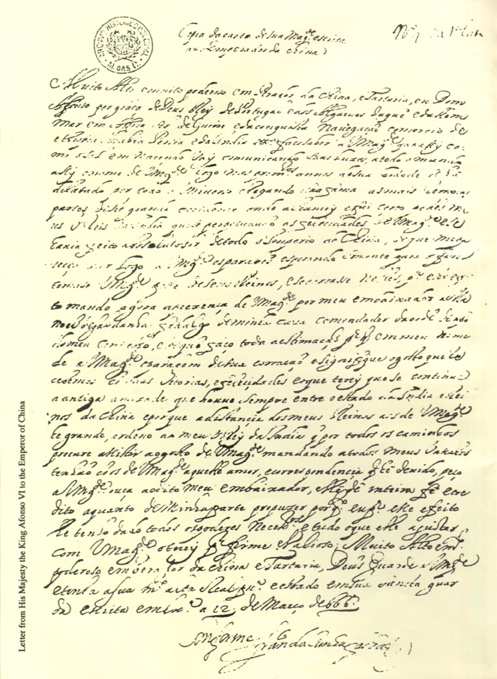

Letter from Majesty the king Afonso VI to the Emperor of China

What we do know for certain is that Kang Hsi later refused to issue a decree against Macau although there were many requests to do so, for [this would] offend a King and a nation which so recently had come to his court to pay homage. 31

In Father Luís da Gama's Diário, there is proof of the diminishing threat against Macau. The borders opened up and although food was not available in excess, the Portuguese were at least able to find enough to live on.

On the 21st of August, the Ambassador went to the Tribunal of Rites to hear the reply the Emperor had given, even though this was not the custom in China. On the afternoon of the same day, the Portuguese embassy set off on the return journey. Saldanha, wearing a blue satin tunic, sat in a chair decked in gold and crimson cloth carried by eight coolies dressed in red tunics. The people crowded onto the streets to watch the splendour. Amongst the on-lookers were some Tartar women on horseback, their heads shaved as was their custom - nevertheless the Portuguese were dismayed at their ugliness.

The boats were richly decked out. The yellow banner bearing greetings and not the character for 'tribute' had been unfurled at the dock. The voyage started on the 7th of August but it was soon to be over for Saldanha, whose state of health was rapidly deteriorating. On the 21st of October, in the city of Huaian, flooded by the Yellow River, the Portuguese Ambassador who had worked so exhaustively within China offered up his soul to his Maker.

Before Saldanha's body had even cooled down, the secretary to the expedition, Bento Pereira de Faria, tried his hand at taking the Ambassador's place. Pereira de Faria, a symbol of a restricted local policy, was both mistaken and imprudent in his attempt as nothing could have taken the glory from Saldanha.

The man who had deserted at Olivença had paid his debt to his country nobly. 32

NOTES

1 "Under Hu Wung's son, Lo (1402-24), plain white porcelain was greatly in favour, and certain types of this, made in is reign, became almost legendary and were subsequently much copied", William Honey in The Ceramic Art of China, p.99.

2 The Chinese, Their History and Culture, 3 rd., p. 287.

3 Concerning the production of porcelain during this period, Honey writes:"the long reign of Wan Li (1573-1619) in many respects continued the styles current under Chia Ching but with diminishing vitality", ob. cit.

4 See C. R. Boxer, Expedições militares portuguesas em auxílio dos Mingscontra os Manchus, 1624-1647.

5 See Semedo, SJ, The History of the Great and Renowned Monarchy of China, p.232 et seq.

6 Semedo, ob. cit. p.20 et seq.

7 Arquivos de Macau, vol. I, p.381.

8 See Boxer, ob. cit., p.20 et seq.

9 See Eloise Talcott Hibbert, K'ang Hsi, Emperor of China, p. 119 et seq.

10 Published in Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo, vol. I, pp.31-41,113-119,181-188,305-310 and vol. II, pp.693-702,747-763.

11 Paris, 1674, p.303 et seq.

12 Ajuda Library, Jesuítas na Asia, vol. XII, codex 49-IV-62, published by C. R. Boxer and J. M. Braga. Macau 1942.

13 A note written by the editors of the Report says that the date must have been 1666 "given that the Ambassador left Goa on the 14th of May, 1667 and arrived in Macau in August, leaving for Canton on the 21st of November of the same year". The apparent error is also apparent in the Chinese manuscripts for in the English translation of China's Foreign Relations, we find "In the name of the King of Portugal, the Governor at Goa appointed another Ambassador to China to investigate the matter with the hope of devising ways and means to solve the problem in 1667 (6th year of K'ang Hsi). He landed in Macau and stayed for more than a year. He arrived at Peking in 1670 (9th year of K'ang Hsi)."

14 Navarrete in his Tratados confirms a stay of two years in Canton.

15 Madrid 1676, p.364.

16 Archives of the Leal Senado in Macau, published in Breve Relação, ed. by Boxer and Braga.

17 Montalto de Jesus, "International tourists in China old and new" in Historic Macao, 2nd ed., p.119 et seq.

18 Glossário Luso-Asiático, vol. I, p. 18 et seq.

19 Father José de Jesus Maria, in his work which was partly transcribed from Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo and later published in its complete version by Boxer in the Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau, states that aytão was the admiral for the province of Canton.

20 Leal Senado document.

21 A complete description of the presents appears in Ch'in Tin To-Ching Hui Tien Shi Li in the section on tributes, vol. CDI, p.1 et seq.

22 In Father Luís da Gama's Diário we find "On the 10th of January, our Ambassador left Canton to go to the Court in Peking".

23 The rank of Te-Tuh was equivalent to that of a general in the West.

24 Montalto, ob. cit., p.120.

25 Breve Relação, idem., p.16.

26 Breve Relação, idem., p.17.

27 Breve Relação, idem., p.18.

28 Breve Relação, idem., p.18.

29 For more information on the ceremonial rituals used for ambassadorial visits, see S. Couvreur, SJ, Cérémonial, p.284 et seq.

30 Breve Relação, idem., p.38.

31 Breve Relação, idem., p.40.

32 The most relevant sources for information on Saldanha's life are: Conde da Ericeira, Portugal Restaurado, Ajuda Library, codex 51-V-10, item 201, National Library of Lisbon, Overseas Section, miscellaneous items, book 4, folio 195 verso.

*Eduardo Brazão served as Portuguese Consul in Hong Kong where he was instrumental in promoting the Camões School and the Hong Kong Portuguese Institute which produced various publications. After experimenting with fiction, he turned to historical research, concentrating on various aspects of the history of Portuguese diplomatic relations, a subject on which he wrote extensively. He was made a Member of the Portuguese Academy of History in 1938 and belonged to a number of other Portuguese and foreign associations.

start p. 19

end p.