§1.

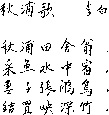

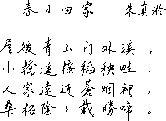

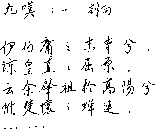

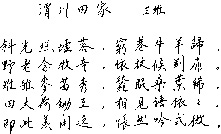

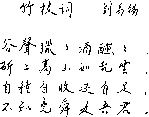

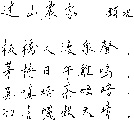

LIU JI劉基 (°1311-†1375).

Born in Qingtian·[city]. Zhejiang·[province].

Man of letters.

LEI CHI NGOK李志岳LI ZHIYUE

1995. Colour inks on rice paper. 23.0 cm x 33.0 cm.

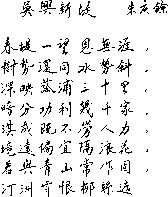

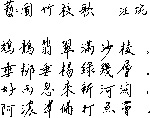

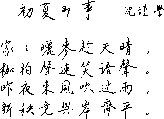

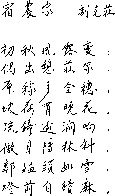

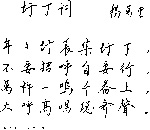

LIU JI劉基 (°1311-†1375).

Born in Qingtian·[city]. Zhejiang·[province].

Man of letters.

LEI CHI NGOK李志岳LI ZHIYUE

1995. Colour inks on rice paper. 23.0 cm x 33.0 cm.

Recently, Chinese literature has become more exhaustively studied by Chinese and Western scholars. Chinese rural poetry is one of the phenomena of Chinese literature which deserves further in-depth research. Its enormous potential can be easily detected by a mere superficial observation For instance, the Qiyue·(July) and Juan Er ·poems in the Guo Feng· section of the Shijing,· have rural tasks for principal theme. Hu Chenggong· says in his Houji·(Later Annotations): "The July poems have for theme the description of agricultural labours. Only through hard toiling all year round can one drink without restrain. It can therefore be said that the people drink the liquor prepared by themselves." Mao Shi Zheng Yi,· mentioning the notes by Zheng Dang· on Zhou Li, ·says: "Each person has their seat according to their age. During spring, summer and autumn people pay less attention to ceremonials and rites. The dead season is the time when respects are paid to the older generations, reenacting the traditional precepts for filial piety."

This confirms that already during the Shi Jing· period there were elaborate poems having for their theme the rural labours. From the Shi Jing and Li Sao periods until the Wei·(AD386-557) and Jin· (AD265-420) dynasties, the literati did not disdain being in contact with the peasants' lifestyles and environments. Thus the literary description of the people's chores by the intellectuals becoming a traditional Chinese expressive form in their continuous search of idealised cannons of beauty. It is possible that the profusion of texts in rural labours in ancient Chinese literature derives from the fact that the literati, usually occupying civil servants posts which constrained them to strict discipline and tremendous psychological pressure, frequently in remote towns, constantly reminisced about the simple agrarian existence of their native homeplaces. The deep contradictions between the riches of official positions and the hardships of peasant living in association with the commonly undefined religious prescriptions of Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism, placed the intellectuals in an unstable ideological world in which they saw 'salvation' through a divesting of material goods and spiritual gains. Early retirement from official positions to rural outlandish locations was a recovery therapy which enabled them to pursue a relatively unencumbered existence till the end of their lives. For the literati living in such isolated places their immediate surroundings were not only the basis of their physical survival but also the fertile ground for their creative freedom and ideological solace. These sources for intellectual stimulus gradually came to objectively create an immensely important body of highly 'aesthetical' works in ancient and classical Chinese literature.

From an historical perspective most of the major ancient and classical Chinese poets described either agrarian themes or hunting scenes in their works: Tao Yuanming, ·Xie Lingyun,· Shen Yue,· Jiang Yan· and Sou Xin,· during the Six Dynasties (AD220-589) period; Meng Haoran,· Wang Wei, Li Bai,· Du Fu,· Chu Guangxi,· Zhang Ji,· Wang Jian,· Liu Yuxi,· Bai Juyi,· Sikong Tu,· and Lu Guimen·, during the Tang (618-907) dynasty; Wei Zhuang,· during the Five Dynasties·(907-960) period; Wang Yucheng,· Mei Guangchen,· Ouyang Xiu,· Wang Anshi,· Su Shi,· He Zhu,· Lu You,· Yang Wanli,· and Fan Chengda,· during the Song (960-1279) dynasty; Liu Zhan,· and Yuan Haowen,· during the Jin ·(1115-1234) dynasty; Yelü Chucai,· Zhao Mengfu,· and Sa Duci,· during the Yuan (1279-1368) dynasty; Liu Ji,· Gao Qi,· Yu Qian,· Tang Yin,· Wu Cheng'en,· and Ji Kun,· during the Ming· (1368-1644) dynasty; Qian Chengzhi,· Wang Wan,· Zhu Yizun,· Wang Shizhen, ·Zha Shenxing,· Ji Yun,· Qian Daxin,· Yao Ding,· and Ruan Yuan,· during the Qing· (1644-1912) dynasty — among many others.

We are not considering rural poetry as the long prose works which describe landscapes and relate the history of China's regions, despite them expressing in a more direct and enthusiastic manner the feelings of the people and the grandeur of the scenery. Although this type of literature is certainly not less highly praised, and in psychological and aesthetical terms it is equally valued to the more intimate poems dealing with rural aspects of the environment, the importance of the later particularly rests in the poets' revelation of the ideal models of literary expressive beauty, and as human beings, the descriptive contemplation of their immediate surroundings and sublimation of their inner feelings.

Li Bai verses:

"Old Farmer of Qiu Pu,

To catch fish, sleeps on the lake.

His wife, to catch white pheasants,

Knits nets in deep bamboo shades."

from his poem Qiupu Ge·(The Song of Qiu Pu) besides being composed with extremely accessible characters and making reference to common daily tasks, also transport the reader to another realm which lies beyond the immediacy of the more explicit meaning of the words. This is a world of distended contemplation, a 'free' brushwork painting, a multilayered world inhabited by nonchalance, sadness, longing, rigour, abandonment and a rejection of society's criteria and material goods. Other poems by the same author, such as Meng You Tian Mu Yin Liu Bie·(Dream visit to the Tianmu mountain) and Jiang Jin Jiu·(A Toast) equally describe real situations shrouded in esoteric detachment. During his years as a civil servant in Sichuan, Wang Shizhen wrote excellent poems. Verses of his such as: "Rice being harvested by labourers, red longzhua branches, glimpsed beyond the forest / Clear sounds from unknown places, the Shanzi singing, at sunset among the yellow leaves." were to become famous in the history of Chinese poetry. It is interesting to observe that in this case the poet left a note about these particular lines. He wrote: "On the way to Sichuan there is a fabulous flower known as 'dragon claws' and an animal which produces a sound as clear as a qing [ancient percussion instrument]. During my first trip to Sichuan during the Renzi year, I wrote a poem about this." The author also quotes the You Huan Ji Wen: "In the Mountain there is no lack of wood, one wonders why is it considered precious."

Besides being an accomplished civil servant, Yuyang Shanren·(Highlander Yuyang) (a sobriquet of Wang Shizhen) reveals in a short phrase, his literati fascination with 'romantic' works and his literary search for stylistic perfection and aspirations to reach the highest calibres of poetical composition: "In the lasty twenty years, learned men from all over the empire have surpassed all excesses of rectitude, outdoing their ancestors in moral values. Meanwhile, the classical music repertoire of their ancestors from the time of the Han and Wei dynasties has been vanishing at an increasing pace. True learned men are extremely concerned about this." From ancient to classical times, the explicit contents of rural poetry saw a shift in value from the real description of agrar ian tasks and the peasants' physical chores to a psychological articulation through the intricacies of Chinese language of the idealization of bucolic scenes. More research needs to be done regarding the transition of the poetical articulation from a tangible and rural perspective of the rural world to an idealised expression of a conceptual landscape, be it minimal or paysagistic.

§2.

The Chinese poems which foremost express rural labour are usually clear, fluid, spontaneous, sentimentally sincere, without artifice, directly relating to Nature, propitiatory, participating and 'synchronised' to the active spirit of field work. The direct expression of straightforward human feelings reciprocates the peasants' behaviour and attitudes. This might explain why they are so popularly acclaimed and their prose found so emotive by all. Zhu Qingyu's verses:

"Endless and spectacular is the Spring Dam,

So are the lush trees streching as far as the flow of water,

Shedding reflections in lakes for thirty li,

And doing good to thousands of families.

So wonderful is the project, and labour-saving,

That it irrigates vast land and prevents flooding.

And if it is kept as solid as the green mountains,

Will the little plains ever complain about being shaded by willows?

of his poem Wuxing Xinti· (The New Dam of Wuxing) describe the many benifits brought by hydrolic works to the cultivation of land, and all the advantages of a landfill derived from the construction of a dam. In this poem, the expression of human feelings of those involved in land works is not that of a carefree and cheerful joy of excessive comfort. The positive mood expressed in the poem is that of a satisfaction by the achievements of manual labour, consonant to the descriptions of faces and minds of the people, in a powerful and magnificent style. This expression of the country is revealed under two major facets, one being the objective description of the agrarian implements and the material world, the other being the representation of firm moral duties. The first description level mainly includes peasants' cottages and villages' public objects, in clear and spontaneous style, both the narrator and the reader clearly participating together in the recognition of popular household items. The second description level makes frequent use of local sounds and colours to support the reader's sensations which identify traditional conflicts and ancestral grievances, the poet renders a composite yet objective rendering of a world where there is a predominant unison the forces of Nature and humankind.

Let us analyse some poems' verses by a few poets, namely:

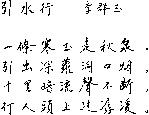

in Li Qunyu's· poem Yinshui Xing (March of the Running Water), the verses:

"An emerald bamboo pipe draws out a cool autumn spring,

Bringing forth steamy vapour hanging over the trailing plants.

Hark, a never-ending murmuring of a hidden stream,

Overhead, flies the gurgling spring!"

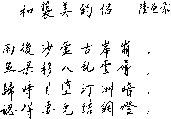

in Lu Guimeng's (ca †881) poem He Gong Mei Diao Lü·(Reply to Xi Mei), the verses:

"The old barrage collapsed after a downpour with sand and mud coming loose.

Behold the spectacle of a good catch swept leaping into the bamboo fishpond.

Walking homewards, we saw a low moon over the beach,

And then, the lamplight by which wife and son were weaving a net."

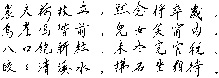

in Zhu Zhenyu's· poem Chunri Tianjia· (A Farmer's Cottage in Spring), the verses:

"The cottage's nestled against the green hill, with a stream flowing by its front-gate.

A little wooden bridge leads to thriving paddy-fields.

Here and there, farmhouses are shrouded amidst spiraling kitchen smoke.

Chaffinches are chirping among white mulberries."

in Wang Wan's (°1624-†1691) poem Yipu Zhuzhi Ge·(Folksong of Yi Pu) the verses:

"Herons and halcyons are swarming over the beach.

Poplars nodding, willows bowing, give life to many a greenbelt.

A rainfall, sudden and opportune refreshes and widens the river.

I'll get ready my fishpond, and then go fishing."

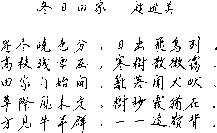

and in Zhao Jinmei's· poem Dongri Tianjia· (A Farmer's Life in Winter), the verses:

"The day is dawning;

Stars are fading.

The sun's come out

And flying birds get in line.

White snow's left hanging.

On the branches.

Wintry trees are gleaming

With thin frost.

The farmer pushes open his door and hears

From the hedges, dogs barking.

The wind's still blowing,

Sending chivers all over the grass.

The tips of twigs are dazzling

With colour beams.

Then, emmerge herds of cattle and sheep,

Filing along the mountain ridge afar.

There stands the farmer,

Stick in hand, envisaging the yearly gains:

Inside the window, are my children laughing.

Eight mouths of my family

Are well-fed and happy,

With the new harvest of rice,

Taxes being paid before the winter's over.

Clear, clear is the little river,

Dusting stone, he sits on it, waiting."

Despite the popular prose of these verses, the moral and psychological rendering of the sorrows and anxieties of Chinese rural workers is made with such accuracy and poignancy that it is deeply heartfelt by those of all social strata.

The popular terminology commonly employed in rural poetry comprises a wide range of terms describing sweetness and sorrows which jointly apply to adjectival states of human emotions as well as conditions of environmental Nature and even the whole universe. Sadness and joy, complaints and praises, are frequently deeply felt feelings which are betrayed by sudden outbursts, but despite this, are sentiments common to all people from all social backgrounds and as so the most important of all to comprehensively express the innermost conditionings of a civilization. Bai Juyi wrote many poems having as their theme the difficult lives of poor peasants. Liu Xizai· wrote about him: Xiangshan·(Fragant Mountain) (a sobriquet of Bai Juyi) uses common words but achieves formidable successes. This is a kingdom most difficult to conquer." Yuan Mei· equally eulogises the poet, saying that he has the talent to "[...] express profound meanings through insignificant words, to uncover sensations of pain through joyful sayings. A thousand years have already gone by; who can rival him in this field?"

Despite much rural poetry being of excellent quality, offering to the reader the possibility to fully taste and wonder about its contents, many Chinese literary critics and literati from later times undermined its value, placing much emphasis on the Confucionist classics and prescribing that"[...] poetry was to reveal the ideal [...] in the same way as [...] the laws of God in Heaven [...]" — a methodology through which they aimed at obtaining fame and credits in the big cities and at the Imperial Court. Gradually, and to a certain point unconsciously, these intellectuals rejected a dynamic, active, and sober lifestyle in favour of more urbane and socialite values.

§3.

The simple basis for the generic empathy on rural poetry was not only that the majority of China's population lived in the countryside but also that most Chinese literati were natives from agrarian homesteads, having grown among the peasants and only moving to town later in life. Also, it should be considered that old China had no cities with a self-regenerating economic structure similar to European cities. Furthermore most wealthy town people were landowners from ancestral families which inherited through generations large tracts of agrarian land. The respect for the ancestors and the veneration for the laws of Nature being closely intertwined, consequentely the love for the land of their kin was deeply ingrained in the innermost feelings of the Chinese. The triad: conscience of land ownership, strong affiliation to one's homeplace and the continuity of genetic rituals, were highly considered by most Chinese people, the literati, being no exception to this rule. Besides the multiplicity of meanings implied by their poems, it is interesting to analyse some of the reasons for their thematics. Rural poetry not only emulated the background of the authors themselves, but it was also a sign of great respect for all the poet's family members — dead and alive — who came from the same place; and ultimately, it was a way of status qualification for those seeking fame and prestige. Qu Yuan's suicide was a tragedy which revealed the liberated mood of his personality. Liu Xiang· (°ca 77BC-†ca AD6) states in his poem Jiutan·(Bemoaning Patriot Qu Yan); his close family and even more distant next of kin have been unequivocally affected by the poet's fame (or infamy):

"He, Qu Yuan, is the son of Bo Yong,

And the last of the noble family.

Being descendents of Gao Yang,

They're kinsfolk of Prince Chu Huai."

Zhang Ying, ·(°1637-°1708) an important representative of the Tongcheng· School and a high dignatary of the government, recurrently referred in his poems to the nostalgia he felt for his homeplace (which he called "Langmian"·("the Sleeping Dragon river"). Some of his works explicitly stated his intentions to build a temple on the shores of the Sleeping Dragon river in honour of his family Zhang where the glory of his ancestors could be perpetuated, implicitely attesting his deeply felt clan devotion, and his high social integrity, ultimately aiming at self promotion within the official hierarchy.

§4.

The length of this article does not enable an analytical study of the origins of all the most important rural poetry's authors. Our approach will therefore be global and we will generalise to the most the complexity of some issues. Chinese literati which were native from the country, or grew, or lived in an agrarian background environment may be divided into three major groups:

4.1. Those who having settled for a considerable period of their lives in a rural place, laboured in the fields and, having intimately shared all daily joys and sorrows with other fellow peasants, straightforwardly transposed them to their poems. These popular Chinese literati belonged to the lowest of their cultured contemporaries' social strata. Their linguistic outspokeness is extremely plain, and even sometimes rather crude, their poems describing the agrarian works in a severe and 'hard' mood. Tao Yuanming who was a low ranking civil servant for a short period of time was also a wealthy landowner. Fang Dongshu·(°1772-†1851)in the Zhao Mei Zhan Yan· says: "Master Tao said he wants no fame or fortune, and he did exactly what he said by retiring to his homeplace where he moans about his existence, his poems conveying peaceful messages." Shen Deqian· (°1673-†1769) says in his Gushi yuan·(The Origins of Classic Poetry): "The poems of Tao are in consonance with Nature. What cannot be reached is his insight and transcendence." Liang Qichao·(°1837-†1927) commentaries are more to the point: "From all the classic writers, first Qu Yuan and then Tao Yuanming are those who best expressed their personalities through their works." Leaving aside the deliberate purpose or the casualness of these authors' intentions, such commentaries are easily understood if we juxtapose the poets' lifestyles with the contents of their poems.

Shen Jinxue,· of Suzhou,· from a family of rural workers of several generations, was a paid field labourer. His work Shen si Shan Shilu·(A Selection of poems from the Shen si Highlander) expresses in an extremely lively and healthy manner the spontaneous joy and naive incredulity of farmers. The authorship of poems with such an in-depth 'visualization' of rural labours as Chuxia Jishi· (Early Summer Harvesting):

"Every household's drying wheat while the sun's shining.

Patterings and clapperings are mingling with laughters.

Last night the East wind blew a good fall of rain over the paddy-fields.

Look, the newly planted rice-seedlings have grown as tall as the barriage."

and Touxian· (Stolen Leisure):

"Only after I'd 'stolen leisure' from farm chores,

Did I realize how long's the summer day.

Alone, I strolled onto the river-bank.

Standing there, I felt cool breeze caressing my face."

are unthinkable from somebody not closely participating in such agrarian tasks. Unfortunately, many of these poets whose compositions relate to us their country surroundings and the toiling of the peasants, were not able to liberate themselves from their lifes' hardships in order to develop their linguistic skills and become more creative. Others composed folkloric poems for traditional songs, progressively elaborated throughout centuries to come. The authors of many of these high calibre tunes are speculative, others are anonymous, and in the majority of the most ancient cases a single authorship is considered to be highly unlikely.

4.2. Those who were from much better-off families, having been given a cultured upbringing and having lived a continuously affluent and leisurely existence. Several of these poets lived luxuriously while successful in high circles and retired to exquisitely selected country abodes when their fashionable fame and fortunes dwindled.

The works of these literati who also wrote poems about the miseries and oppressions of human existence usually comply to the literary Guan Zhao·('contemplate and enlighten') style. Such poets interpret rural labour as embellishing components of anenveloping appreciation of the landscape, their poems expressing the marvels of the natural kingdom. For instance, Wang Wei's (°701-†761) poems: Chunzhong Tianyuan Zuo·(The Countryside in Spring):

"Turtle-doves are cooing on the eaves.

Apricot trees're blossoming by the village.

An axe's raised to chop mulberry branches,

A hoe's picked up to trace a hidden spring.

Returning swallows know their way home,

An old dweller peruses a new calendar.

Raising the wine-cup, he has no wish to drink

Sadly remembering loved ones far away."

and Weichuan Tianjia·(Village Life on the Wei River):

"The setting sun's shining on the village,

Cattle and sheep're returning to their humble lanes.

Leaning on his stick, standing by the gate,

An old man's anxiously waiting for his shepherd boy.

Pheasants' chirping hastens the thriving of wheat.

As silkworms sleep, mulberries grow bare of leaves.

Hoes on shoulders, farmers are passing to and fro.

They greet warmly as they meet but reluctant to part.

How I admire them for their leisurely life,

Sadly, I recite the poem Shi Wei"

are praiseworthy by their invigorating descriptions. But from a more careful reading transpires the distance between the embellished concept of the poet to the harsh reality of the situation. An even more detailed analysis of the language of these poems establishes that the terminology used by the poet to denote rural aspects is really from the realm of the landscape. Wang Wei, born in a noble family, despite its multiple talents, does not manage to accurately describe situations and sensations which he never experienced. Under the protection of Zhang Jiuling, Wang Wei held a number of important positions (Youshiyi,· Yushi, · Libu Langzhong· and Jishizhong·) at Court, after his forties interspaced by long periods away from official duties. According to the Jiu Tang Shu·(Old Book of the Tang) he and "[...] his friend Pei Di,· exchanged visits by boat, and together played musical instruments and composed poems [...]." Such a lifestyle produced poems about tears of refined elegance and fraternal sympathy towards peasants who toiled all day long with their backs bent towards the earth and exposed to the scorching sun.

Liu Kezhuang,·(°1187-†1297) who lived during the late Southern Song, although having gone through extreme difficulties and seriously adverse conditions during his long official career in times when "[...] the future of the country was as volatile as smoke [...]" achieved promotion to a series of successively higher posts (Xinaling, · Shumiyuan, · Bianxiu, · Shumiyuan Youlangguan, · Zhizhou, · Taifu Shaoqing, · Mishujian ·and Zhongshu Sheren·). He praises Yang Chengzai· verses with the following phrases: "A good harvest does not depend on the supremacy of the xiao ·[a vertical flute] but on the clamour of the threshers in all the villages. [... And...] regarding talent Fangweng is akin to Du Fu; but regarding talent Chengzai is akin to Li Bai." His words are far from expressing the hard realities of agrarian tasks; also that he held Li Bai in more consideration that Du Fu. The poems where he describes rural labour are steeped by strong artificiality. For instance, in his poem Su Nongjia·(Staying Overnight at a Villager's Cottage), he uses the character qi· (to relax, to rest) in close psychological affinity to the literary Guan Zhao style, and the character lin· (neighbour) which implicitly expresses a real distance between the poet's lifestyle:

"So refreshing is the early autumn breeze,

I wander out and put up for the night in a village.

Nodding golden ears fill up the paddy-fields,

Still in bloom are the late lotuses down the brae.

Intermittently ring the bells over the ravines.

The moon, turning sideways, beams on the trees.

Grandma, next door, with hair as white as snow,

Is twisting hempen threads under a lamp."

4.3. Those who, frustrated by their official careers, prematurely stepped down with the loss of honours into less favoured social circles, or were simply demoted following conflicts within the course of their duties. These poets day-dreamed of being readmitted as civil servants and promoted to higher echelons and even, perhaps to becoming high dignitaries and noblemen. Aware of the enormous sufferings and the great misery of the Chinese people, these poets came close to the rural milieux not to partake from the peasants' lifestyle but to become enthralled by a 'falsely' pure 'Nature', rejecting its darker and fiercer aspects. Joining peasant communities later in their lives, their contact with the agrarian world was short-lived and their plaintively whimpering poems rather express a personal than a global dillusionment of the ruling powers. Qian Chengzhi,· (°1612-†1693) after retiring from the Hanlinyuan Shujishi· post, left for the country where he lived a decadent existence, writing poems about his rural environment full of personal anguish and commiseration. His poem Shuifu Yao·(The Song of the Boatmen) has the following verses:

"We've just brought you up to give us a hand,

And can not help weeping, to see you off at the gate.

Even leftovers're gone to appease eagles' hunger.

We all await your return with a good catch."

an open exposé of his deepest sorrows. Another of his poems Tianyuan Zashi Zhier·(A Second Miscelanea of Country Poetry) reveals his state of extreme loneliness veiled under less extreme prose:

"So clumsy was I ploughing the field

The old farmer took pity on me.

Relaxing the yoke he made the ox work for me.

He taught me the ways to make the ox obey.

It was so arranged that right after the autumn harvest

I'll thank him with wining and dining."

In others, such as Cui Liang Xing·(Grain Gathering Trip), Huo Dao Ci ·(Rice Harvesting Verses) and Zhuo Chuan Xing·(Boat Seizing Excursion), Qian Chengzi makes use of aggressive and penetrating terminology to shockingly impress the reader. Be it bitterness or hatred, or even sporadic bliss about his condition, the poet portrays his poems' protagonists as human beings — negating titles and honours —in search of their primordial 'Nature', and makes full use of his linguistic skills to confirm and reassure the reader (and himself) that life is marvelous and splendiferous.

§5.

The three mentioned groups represent survival typologies, related to life's opportunities and people's personalities, which shape and condition poetic creativity. It was within the indicated constraints that rural poetry flourished and acquired its particular characteristics. True ancient and classical Chinese rural poetry of the literati who held official positions or were from wealthy backgrounds and equipped with a vast cultural background composed at leisure, and those of more lowly upbringing who seldom toiled in the fields and occasionally wrote for pleasure, expressed life's values and the feelings of the people as human mortals according to the peasants' psychological criteria. This is not to say that linguistic embellishments and idealised thoughts clashed with the dismal survival conditions of most Chinese, who belonged to a basically agrarian civilization, but frequently they diluted and distorted the realities of the poems' selected theme, giving a visionary interpretation which is the outcome of patterns of the poet's affluent life in the cities. "It became normative to interpret history in general as the evolutive 'history of towns', making no distinction between these and the vast rural areas (and here, these 'urban microcosms' can only be seen as elitist carbuncles in the global economic regime). But, [for instance, in Germany] during the Middle-Ages the rural communes became the starting point of a new turn in history, an unprecedented evolution from a previous clashing stage between towns and the land." In China, it was only during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) that certain urban sectors became self-regenerating and that merchants made fortunes based on a capitalist trade system. The conflicts between the country's minorities which occcured in the following centuries, and later in the nineteenth century the invasion of the empire by the foreign imperialist powers, operated a transformation in the interpretation of Chinese civilization from a traditional narrative process to the 'modern' and independent 'history of towns'. This novel interpretative process came to reverse the order of priorities disregarding that during millenia all Chinese, regardless of their rank, or social status, intellectuals or not, were absolutely dependent on an agrarian infrastructure which prevailed in all the Far East. In that respect, and because primordially all clans and families evolved in rural environments, the works of the overwhelming majority of ancient and classical Chinese literati were connected to traditional simple, peasantry values derived from their daily chores in the fields. Rural poetry is the most direct and open literary form to artistically express the inner feelings of those who lived in contact with the earth. Although the analysis and interpretation of rural poetry unfolds multiple facets of the Chinese literati's idealised human conduct and lifestyle, that is not to say that other prosaic genres also unravel a multitude of hidden behavioural meanings; just that the former style is closer to the true essence of their human origins, which they incessantly attempted to recreate in unison with Nature. Lastly, this more plain type of 'transparent' poetry gives us access to decode more elaborate poems where situations and feelings are concealed in the artifices of composition and alluded to through obscure symbol

§6.

In rural poetry, the aspirations and motivations that the traditional literati idealised to express, can be divided into three major categories:

6.1. The search for a perfect lifestyle, and ultimately, for enlightenment. Through their intellect and literary talents, to criticise contemporary society and the environment. To manifest enthusiastically the positive aspects of human existence, a state of being which is frequently specifically expressed through the 'realistic' description of the agrarian labours. These are apparent in the verses of Liu Yuxi's (°772-†842) Zhuzhi Ci (Ci Poem - A Folksong):

"The threshing of grain, intoxicating wine...

Hay piles up like the rolling clouds.

I sow, I harvest, and I'm self-sufficient,

Knowing not wether Yao or Shun's the emperor."

of Yang Wanli's (°1127-†1206) poem Xuliao Ci (The Song of Labourers Working on the Dyke):

"Every year-end the Leader gathers his men

Who will come voluntarily to work on the dyke.

At one go rammers tamp down scoops of earth,

And in unison they sing chants solid and touching."

and of Sa Duci's (°1308) poem Changshan Jixing· (Travelling in Changshan).

"It cleared up after a fall of rain, with streams trickling away.

The village, from north to south, was enchanting with wood pigeons singing.

The traveller didn't feel tired in May

And was pleased to hear the threshing of wheat."

These transmitals of experienced situations by the authors, although aiming at describing a relatively developed agriculture, go beyond contemporary realities into far-fetched illusory situations, Chinese expertise and manpower of those times being unable to salvage crops from natural calamities. But to express these as a testimony of hope and confidence in their fellow contrymen must be considered the proof of an extremely positive and sincere interest and attachment for the efforts of man in relationship to Mother Nature. Cunning rulers and literary patrons were able to exploit in their favour such elated figures of speech by deeply motivated poets. Frequently, promoting their interests as well as favouring the vanity of the literati, they conferred honours and favours, in exchange for promisory literary works emulating the grandeurs of the country juxtaposed to a more humble nostalgia for native landscapes. Lord Chen Yinke· after being summoned by Cao Cao·(°155-†220) to look for talented people, had a piercing hindsight, which he described in the following manner: "The three orders given by Cao Cao foretell that in general from all people of good morals not all have great talents. But in fact from those people with good morals many are who disdain filial piety, kindness and justice, being criminally corrupt to the piont of declaring that the golden rules and the precious precepts that the literati civil servants so much respect have become radically frustrated [...]. Nonetheless, these three orders can be considered as a manifestation of the Wei Court politics controlled by Cao Cao. Furthermore, it is certain that all those who might express opinions against Cao Cao, even if they are his followers and friends, will be immediately considered his enemies and put down." And Shi Runzhang· says: "The greatest preoccupation of the literati civil servants is not to be removed or demoted from their official positions; and those who would rather resign, constrained by gross injustices, are foremost concerned in saving their face. Frequently victims of frustrations, they reach a point of no return. I remember meeting a fat, cheerful man who confided to me having had luck in his civil servant career. Several years later I met him again, but his face was so pale and sucked in that I hardly recognised him. I asked him what was the matter with him and he told me that he had lost his post and honours." Promotions and demotions, rises and falls, in fact all factors, can contribute to the 'real' poets of ancient and classical China to reveal their idealised aspirations.

6.2. The search for psychological tranquility, and ultimately, for detachment. The close practise of Buddhism and Daoism by many literati frequently lead them to esoteric realms of existence difficult to reconcile with their official duties and society's more realistic norms. Wang Bi·(°226-†249) says in his Lao Zi Zhu(Notes on Lao Zi): "Because everything comes from the void and movement results from immobility, all moving matter ends being void and immobile. This is the final destiny of all beings." This saying by Wang Bi is in conformity with the Laozi Liezhuan·(Biography of Lao Zi): "Instead of seeking for fame, Lao Zi depurates morals as a mere pretext for retirement." Also along these lines is Zhuang Zi's· (°ca 369-†286) saying in Zhuang Zi: Tianxia Pian·(Zhuang Zi: Chapter of the World): "Guan Yi· says he has no belongings and that other people's possessions cause him great discomfort. He is as free as water and as undisturbed as a mirror." This philosophy of thought would prevail for many centuries. Chinese literati embraced destitution and tranquility as prerequisities to conquer this 'worldly kingdom' which was their ultimate goal. In order to create this conceptual 'kingdom of life' where the intellect was at rest and cultured simplicity and immaculate beauty, secular matters were to be discarded, social conflicts were to be disdained, and the world of Nature was to remain undisturbed. The verses from Tao [Yuanming's] Qian poem Yinjiu (Wining and Pondering):

"I made my home amidst the earthly lot,

Yet, so unearthly is it, tranquil and free

From the madding crowd. How's that?

An ethereal existence transcends the worldly.

Picking chrysanthemums yonder the hedge,

Looking up, perchance, I caught sight of Nan Shan.

Behold its beauty at sunset, and

Homing birds are already on their way back.

There is so much truth in this reality,

And yet, I find no words to explain it.

and those from Gu Kuang's (°ca725-†ca814) poem Guoshan Nongjia (Visiting a Farmer's Home in a Hilly Village):

"Crossing the wooden bridge, I was enthralled by the gurgling below.

Under the thatched roof, in the midday glow, the quiet was broken by the cock's crow.

Ah, don't worry, please don't bother about the tea-leaves smoky.

What a pleasure it is to dry grain in the beautiful sunshine!"

relate to a lofty world within this world, a wonderous, gratifying and remote refuge, a salvation shelter after a tempestuous life's itinerary. But one must also admit that for the intellectuals there was no other alternative beyond Zhuang Zi's doctrine and that the status of a literati, besides their life's successes or failures, automatically carried the obligatory task of the idealization of a supreme and sublime 'planet', the expression of this achievement being attested in their poems of blissful and timeless contemplation, extraneous to social conflicts, courtly intrigues and the wars of the empire. The Jinji –Zonglun·(Digest of the Annals of the Jin Dynasty) says: "Candidates to government positions consider a blessing all that they gained with so little effort, and consent to wrongdoings admitting them as correct decisions. These civil servants obey their superiors with a sheer lack of diligence and prudence [...] Liu Song repeatedly says that is necessary to fortify moral principles but it is known that all those who are truly committed are taken as petty officers, and that only those who flatter their most important superiors will achieve consideration in all the land [...]as this is so much in verity that fame and calumny are spread without distinction of good and evil, and the selected for government posts are those who strive to make private entities richer and in their turn the government officers act in their interests as if they were private entities [...]. Everywhere there are people anxious to become civil servants. There is not a single one among the thousands of government officers who is willing to hand over his post to a competent and talented person." Trapped in this web of deviousness and contradictions, the literati sought vindication in an ideal shelter where "[...] land was flat, housing was ruled, soil was fertile, water was plentiful, there were bamboo forests and mulberry trees, cross country lanes, the sound of cockerels and dogs on the air, those farming the lands dressed as they were visitors, and happy children with dishevelled hair." It is not difficult to grasp that the poets, through their descriptions of psychological conditions or landscape actions exteriorized their innermost desires to recreate an ideal vital attitude consonant with unrestricted Nature and the endless cycle of renewed origins.

6.3. The search for the achievement of total perfection, and ultimately, for supreme aestheticism. Although the outer world of stratified and compartmentalized society prevented the realization of their ideals, intellectuals found solace and extracted unhindered creativity from their inner world, become aloof and disdainful of mundane matters and established utopian parameters to an imaginary Nature. Entrenched within themselves as entities separated from the reality of 'potentially significant' events, the poets acquired by negation an alternative strength whose outlet was the creation of works of consummate aestheticism. Immanuel Kant (°1724-†1804) says that the connections engendered in the production of beauty are strictly bound to sensations of delight; and his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) states that delight is effective to all human beings — a sensation that varies from person to person irrespectivelly of the creative process and final outcome of a work. Diderot says than human beings have the tendency to be elated by the order (beauty, or style and arrangement) of a work regardless of its utilitarian qualities. [...] It is common to see people admiring the beauty of flowers and trees, and the myriad forms and shapes of Nature without knowing or enquiring about their original purposes. To mould an object or a situation from a particular perspective according to the Guan Zhao principles of contemplation and enlightenment, developing a spiritual awareness of common values, is to assume a dignified mortal position. It can not be denied that the poets who dwelt with rural poetry themes generically attempted to transcend their personal dissensions with the society they were in to put forward a challenging modus vivendi in unison with Nature. This option derived from the search for the reenactment of primordial instincts and the reformulation of ingenuous purity, formulas devised by the poets to compensate the apparently unsolvable contradictions and complexities of a brutal ruling social structure which dominated their destinies and asphyxiated their outspokeness. The exclusion of an active political and social participation by the overwhelming majority conducted to the stagnation of people who had reached (illusory) decision making positions who, being traditionally forced to abide to confucionist hierarchical rulings, were also prevented from returning to the original agrarian condition of their ancestors. This malaise of imposed life patterns for most and their impossibility of non-return to their native places developed intense nostalgia and, as consolation and reminiscence of lost joys, an adherance to rural poetry. This spectrum of situations is admirably condensed and personified in Lu Xun's·(°1881-†1936) Kong Yiji. It is also obvious that the literati derived much self contentment in their creative and productive processes elaborated according to the principles of contemplation and enlightenment. In fact, the changes of effective poetical struggle and contestation were nil, their works bringing philosophical solace and spiritual comfort to just an extremely limited number of cognoscenti adherents. The peasants and those of the lower classes never, or extremely rarely, came in contact with contemporary poetry emulating the grandeur of their daily hardships. And, if minor poets were envious of the great poets' material affluence and spiritual intensity, the reality was that the hierarchical gap was such that those belonging to the lower classes could not grasp the aloofness of the consummate intellectual prosers — only one thing bound them together, their loyalty to the emperor!

§7.

In conclusion, this work does not attempt to invalidate the historical status acquired by the ancient and classical Chinese literati but proposes that, through a deeper analysis of the sources and purposes of rural poetry, many poets remained in heart closer to their origins despite attempting to conceal these in figures of style for recognisable and laudatory aesthetic intentions. Numerous rural poetry works by more traditional poets constitute a significant corpus in its own right, spanning many centuries of production, and equally supreme in perfection, autonomy, simplicity, straightforwardness and contentment. But furthermore, they are also the expression of a conflicting duality, as they attest for the making of a millenary nation through the struggles of their responsible and dedicated people, as well as speaking for the weaknesses of poets looking at the communion of those of their kin with sovereign Nature from a comfortable, telescopic distance.

Adapted from the Chinese by: Zeng Jiang 曾江. Poems translated from the Chinese by: Ieong Sao Leng, Sylvia 楊秀玲 Yang Xiuling

* Lecturer at the Chinese Department of the Jinan University, in Guangzhou.

start p. 87

end p.