17

. </figcaption></figure>

<h3>

THE CHURCH AS THE SCAPEGOAT

</h3>

<p>

The Kyushu campaign was gradually proving successful. The Shimazu troops withdrew from Chikuzen, Chikugo, Hizen, Higo and Hyuga and the Satsuma survivors drew back to their own fortifications. On the 9th of May 1587, Shimazu Yoshihisa, who had been overthrown in favour of his brother Yoshihiro<RETLAB2001700120019><a href=#"LAB2001700120019") name="RETLAB2001700120019">18</a>, surrendered to Hideyoshi at Taiheiji Temple in Sendai, the northern entrance to the daimyo) 19

19

The nine Lords of Kyushu had sworn allegiance but Hideyoshi's chronic mistrust was not allayed because he saw his throne supported by local powers who might well wish to overthrow him. Only a few of these and some of the generals of his own army were Christians, but many others might well seek their support to overthrow him. The time had come to deal the death blow, by means of a ploy that had been planned beforehand20, using the Church as a scapegoat.

During the night of the 24th of July 1587, Hideyoshi decreed that all Jesuits should be banished from his realm, and demanded that the Japanese, above all senior military officials who had been converted the previous year, should renounce their new faith. At the same time, he revoked the grant of land in Hakata which he himself had given to Coelho on the 19th of July. He further took over the port and city of Nagasaki, of which the Omura daimyo had allotted a certain share of the revenue to Cosme de Torres some years previously. 21 He closed down the churches in the city and subsequently ordered that those in Miyako, Osaka, Sakai, Settsu, Harima, Mino and Owari should be destroyed. 22 In the course of his reign two hundred Christian churches were dismantled.

HIDEYOSHI GIVES IN WITHOUT GIVING UP

In spite of this, Hideyoshi took care to safeguard his own trading interests and was very lax and ambiguous about the application of the banishment order. Gaspar Coelho helped to establish a truce by means of correspondence and gifts to the ladies of the Court and to Kita no Mandokoro, Hideyoshi's legitimate wife who pleaded the cause of the Jesuits who had been condemned. Wearing peasants' clothes, the latter spread out through the lands of friendly daimyos who were not afraid of putting their property at risk or even their own lives.

In order to reduce Hideyoshi's fury, Alessandro Valignano, the Visitor, in his capacity as the Legate of the Viceroy of India, called on him in 1592, in the company of four young Japanese legates who had left for Europe some ten years previously. The delegation presented a solemn air and their gifts pleased the dictator. The Visitor did not, however, think that it would be wise to ask him to revoke the edict of banishment. The following day, Hideyoshi informed Valignano that he would be permitted to remain in Japan until the next Portuguese ship set sail, but that he would be required to leave behind in Nagasaki ten of the other members of the Embassy as hostages. 23

Seventeenth century drawing of the martyrdom in Nagasaki in 1597. João Rodrigues is shown as one of the two priests in the centre (in Chrónicas de la Apostolica Provincia de San Gregorio, Manila 1744)

Seventeenth century drawing of the martyrdom in Nagasaki in 1597. João Rodrigues is shown as one of the two priests in the centre (in Chrónicas de la Apostolica Provincia de San Gregorio, Manila 1744)

Even so, whilst Valignano remained in Nagasaki with the rank of Ambassador, certain powerful nobles such as Iki no Kami, Yakuin and others, still smarting at not having been invited to the audience in Kyoto, spread rumours that the Embassy was merely a front. Valignano refuted this slander, but Organtino and certain lay nobles in the capital sent word to the Jesuits in Kyushu warning them to close down the college and the novitiate and then go into hiding. None of these houses, the Language School, the Painters' College or the Printing Shop in Nagasaki were actually closed down but they did change their residence several times. 24 Some of the churches were redecorated to look like private houses and the remainder were closed down. The Governor of Miyako told João Rodrigues Tçuzzu25 that the Jesuits could remain in Japan but they should wait until Hideyoshi died, before continuing with their apostolate.

Another attempt was made some four years later. The Jesuit Bishop, Pedro Martins26, arrived from Macau on the 14th of August 1596, as the Legate of the Viceroy of India. His audience with Hideyoshi in November was also staged with due pomp and circumstance. As an act of deliberate hypocrisy, the dictator stated that he would allow the missionaries to remain in Japan, but on the 4th of January 1597, a group of six Franciscans, three Jesuits and seventeen lay brothers were escorted out of the capital by soldiers to be crucified. Previously they had been sentenced to die on the cross in Nagasaki, but the sentence was only carried out on the 5th of February. 27 Furthermore, in March, Hideyoshi confirmed in writing the banishment order dated 1587. 28

BRIEF PERIODS OF UNCERTAINTY

Hideyoshi died on the 16th of September 1598, leaving a council of five regents29 while his son was still under age. However, extreme prudence was required. Temporarily, Cequeira and the Visitor withdrew to the Islands of Amakusa in 1599 to learn the language. The missionaries, led by Pedro Gómez, remained at their posts and built some chapels in the Arima area.

The suprising fact is that, even during the campaign to invade Korea30, Mori Teramuto, one of the regents who was famous for his bitter hatred of Christians, expressed the wish to have some priests at his castle in Hiroshima. 31 In point of fact before he was punished in 1600 for his behaviour in the Battle of Sekigahara when his estates were reduced to little more than the fiefs of Suo and Nagato, he allowed Pedro Pablo Navarro to start rebuilding the church in Yamaguchi. 32

In spite of having no missionaries, the Christians had remained true to their faith since the time of Xavier. 33 Each year, Navarro visited his flock scattered by feuding in Suo, Nagato and Bungo. 34 Nevertheless in 1602 Terumoto gave in to the pressure from the bonzes and the mission was completely closed down. Three years later, it suffered its first martyrs who had been preceded by others in the fiefdom of Higo, which is now Kumamoto, following in the wake of the persecution started by Kato Kiyomasa. 35

THE 'GOLDEN AGE' OF THE CHURCH IN JAPAN?

Hitherto it has been said that this was only an unfinished print that Pedro Gómez, the Vice-Provincial, managed to see before his death in Nagasaki on the 21st of February 1600. Between 1598 and 1604 the Jesuits had baptized some 86,000 throughout the whole of Japan and the Franciscans had converted some five hundred people as a result of their first efforts. 36

The political situation was critical. The regents' ambition caused them to fight the Battle of Sekigahara on the 21st of October 1600, where they were defeated by the followers of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Various leading Christians were executed as part of his revenge, the main one being Konishi Yukinaga Agustín. In 1601 Valignano wrote of vain hopes adding that only in the cities of Nagasaki and Miyako was there any real freedom of action. 37

The description of the first ten years of the seventeenth century as being the golden age of the Church in Japan 38 is open to question, because Ieyasu was a carbon copy of his predecessor. Following his victory in Sekigahara, he was the real head of state before being appointed shogun and he did not welcome the visit of certain members of the mendicant orders in 1602. The Jesuits expected the situation to return to the dark days of Hideyoshi.

Even so, in the initial stages [Ieyasu] took a benevolent attitude towards the Church and, on more than one occasion, gave it valuable assistance. 39 However, he did not raise any objection to Mori Terumoto's persecution in Suo-Nagato (1603)40, nor in Amakusa and Bungo (1604), or Satsuma (1606), Buzen (1611) or the chronic persecution taking place in Higo and Hirado. 41

From 1606 onwards Hideyoshi's edicts were still in effect and would probably never be revoked. Three Christians were beheaded on the island of Ikitsuki in 1609 together with four more in Yatsushiro, one being a child of twelve and another affectionately known as Pedrito (after the Spanish custom) who was only five. 42

The Jesuit Vice-Province of Japan became a fully-fledged Province in 1611. 43 The following year, 1612, was a key date in the history of the persecution of the Church in Japan. Tokugawa Ieyasu in Suruga (wnow Shizuoka) and his son Hidetada in Edo (Tokyo) both revealed their true colours and displayed openly their irrational hatred of the Christian religion. 44 Their example soon spread throughout the whole nation.

NATIONAL PERSECUTION: EXODUS TO MANILA AND MACAU

The plan to stamp out Christianity had been put into action and the only thing missing was the signature on the definitive edict. In spite of having abdicated at Hidetada in 1606, Ieyasu was still the de facto shogun and signed the edict on the 27th of January 1614. Twenty seven years had gone by since the first edict had been issued by Hideyoshi in Hakata.

On learning of this at Miyako on the 14th of February 1614, Gabriel de Matos hurriedly wrote45: an Apologia which I delivered to the Governors of Mikayo and Osaka, I left Osaka on the 25th of February of 14[]. We shall have to wait for the Autumn. 46 Following his example, Diego de Mesquita sent another apologia to Governor Hasegawa Sahyoe in Nagasaki. 47 Neither of them had any effect.

The number of monks and priests in Japan at that time amounted to one hundred and forty nine, one hundred and fifteen being Jesuits, fifteen Franciscans, eight Dominicans, four Augustinians and seven diocesan priests. 48 The victims of the banishment gathered in Nagasaki between March and October, and several of them made the most of the waiting time in order to visit secretly the Christians living on the Island of Kyushu. On the 28th of October 1614 they were sent from Nagasaki to the nearby port of Fukuda. 49

Apart from the official vessel from Macau, there were various junks at anchor and many of them piled into these in order to get away. The former which was probably on its way to Siam, calling at Macau en route, weighed anchor shortly before the 6th of November and the Jesuits could only take three priests and three brothers. 50 The remainder were divided up between the three junks which sailed from the port on the 6th.

Twenty three Jesuits sailed in the vessel going to Manila -including51 fifteen Japanese brothers52- plus twenty five or twenty six monks from other orders including fourteen monks from Miyako no Bikuni53, Tome dos Anjos the Japanese priest and a group of lay brothers who had voluntarily gone into exile, sixty two Jesuits and fifty three dojukus54 (twenty eight of whom were studying at the Seminary) apart from the Japanese priest Paulo dos Santos.

Contemporary copy of Hideyoshi's decree(one of the fifteen banishing the missionaries from Japan) July 1587.

(Matsuura Shinjo Museum, Hirado)

Contemporary copy of Hideyoshi's decree(one of the fifteen banishing the missionaries from Japan) July 1587.

(Matsuura Shinjo Museum, Hirado)

CLANDESTINE WORK

Twenty seven Jesuits, seven or eight Franciscans, five Dominicans, five Dominicans, three Augustines and five Japanese diocesan priests went underground and remained behind in Japan55 but the authorities pulled down all the churches with the sole exception of the Misericordia for the foreign merchants.

Philip II of Portugal (III of Spain) appointed three Franciscans to the official embassy. 56 They arrived in Japan at the end of 1615 and proceeded to the capital, but Tokugawa Hidetada refused to receive them, handed back their gifts and detained the legates until the winds became propitious for the Portuguese vessels to leave. 57

A new law was published in 1617 sentencing any missionaries who were found, together with those who had given them shelter, to be burned at the stake. 58 Constantly moving from place to place, one of them, Jerónimo de Angelis, paid a secret visit to the court dignitaries who had been exiled to Tsugara since 1614. 59 He was soon followed by Diego Carvalho to the same area whereas the others, several of whom had arrived secretly in Japan, visited all the landlords once a year.

Both the Christian missionaries and the converts themselves who had gone underground fully understood the risks that they were running. As a precaution they never stayed more than ten days in any one place. Some disguised themselves as 'shaven heads' and yet others as common soldiers. 60

On the 18th August 1618, the Visitor Francisco Vieira disregarded the opposition of his counsellors, and went from Macau to Japan because of a rumour that Couros was not respecting his religious vows. 61 On arrival he was relieved to discover that the rumours were untrue. His visits to the missionaries and to the groups of Christians were restricted to going from port to port in a small boat. 62

The missionaries would turn the days into nights and vice versa. 63 A few days later Couros wrote that there were thirty one Jesuits in the whole of Japan (twenty four priests and seven brothers, of whom eight were Portuguese, seven Italian, and five Japanese) and explained where each one had been. 64 In 1618 Tokugawa Hidetada tolerated the Christians in Nagasaki because he did not know that there were still any priests, because the Christian Governors would hide them65, as did the pagan daimyo who had succeeded Miguel de Arima. 66 However in 1619, speaking on behalf of the shogun Hidetada, Heizo Suetsugu, the apostate governor of Nagasaki, tried to persuade the missionaries being emissaries of the King to leave Japan of their own free will. Certain Portuguese traders who were thinking only of their own interests supported this idea. 67

COVERT REINFORCEMENTS

In contrast, the pastoral care of the Christians who had been persecuted since 1615, moved the monks, diocesan priests and dojukus to devise ways and means to outwit the vigilance of the authorities and the spies. One notorious example was the arrival in 1617 of eleven Franciscans, four Dominicans and two Augustinians. 68

With regard to the Jesuits, in 1968, Professor Josef F. Schütte published a detailed list of the entries, departures, martyrs, deaths and resignations of the monks and some of the dojukus who had been expatriated but had entered the Society in order to return to Japan. 69

Their hopes were to be dashed, however. On the 20th of September 1620, Date Masamune, the daimyo of the northern provinces who had years before tricked the Franciscan Luis Sotelo with false promises, issued an edict against the Christians. The persecution began on the 27th of November. 70

In August 1621, a proclamation was issued in Nagasaki sentencing all those who gave shelter to priests to be put to death, and almost all Christians, with the exception of some poor people, withdrew sanctuary for the monks and their dojukus. 71 Informers were rewarded with 130 cruzados. 72 Some one hundred and fifty apostates joined together in Nagasaki to hunt down the priests. 73 As far as possible they used this money to help the widows and orphans of the martyrs. 74

In 1622 Hidetada abdicated from his position as shogun in favour of his son Tokugawa Iemitsu. Official sadism exceeded all limits during his reign. In 1634, in the presence of his ministers and foreign ambassadors he listened to an "Apologia of Faith" written by Sebastião Vieira, who had been sentenced to death. The shogun recognized the innocence of the missionaries but he changed his mind when one of his ministers reminded him that he had been appointed shogun under oath to eradicate this religion from Japan. 75

BESIEGED IN NAGASAKI

In 1634, all Japanese Christians who had not apostated were forbidden to leave the city or enter Japan. 76 Iemitsu refused to receive the legates from Manila, because they included Luis Sotelo who had returned from Europe and declared that as from 1625 all trade with the Philippines would be outlawed. 77

That year a new decree came into force in Nagasaki forbidding the conversion of adults, the baptism of children together with the distribution of the Christian calendar. No European vessels arrived in Nagasaki that year. 78

In 1626, he compelled the Christians to declare the savings that they were using in their business and these were tantamount to frozen by the authority of Mizuno Kawachi. Henceforth, no Christian was allowed to visit the houses of the Portuguese nor store their goods; and the 'mechanics' lost their jobs if they failed to respect this order. 79

The annual letter for 1626 reads:

Francisco Pacheco, the Provincial priest went to heaven due to his martyrdom together with Brother Sadamastu Gaspar, Father Juan B. Zola, the Rector and Father Gaspar de Castro due to illness, or, as another author states, due to the many difficulties and setbacks that they suffered as a result of so many searches and upheavals.

The spies were extremely efficient in searching for the others, above all Mateo de Couros, the Vice Provincial. 80

He himself wrote:

They sent several soldiers... with orders to search all the houses as thoroughly as they could. They went about their work without leaving a single house, cabin or stable unsearched from top to bottom... [but] this was before my host had managed to arrange a priest's hole about which the others knew nothing.

It was four spans wide and twelve long. I would hide in here with my dojuku and the servant who looked after us, without any light at all. When meal or prayer time came or when writing letters to our brothers, a candle was lit and as soon as the work was done, this was snuffed out. Food was passed to us through a a small slit which was opened to hand in a bowl by pushing back the straw of the neighbouring wall where an old farm worker lived, and then closing it immediately. Every three days or so the entrance to the pit was opened in order to meet certain pressing needs... I spent thirty five days with my companions in darkness... After that the owner built another priest's hole on the other side of the hiding place, but it was the same width and length.

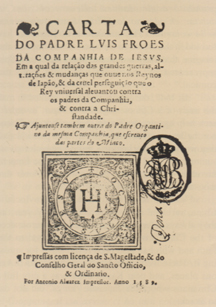

"Carta do padre Lvis Froes da Companhia de Jesus en a qual da relação das grandes guerras, alterações & mudanças que ouve nos reynos de Japão", Lisbon, 1589.

"Carta do padre Lvis Froes da Companhia de Jesus en a qual da relação das grandes guerras, alterações & mudanças que ouve nos reynos de Japão", Lisbon, 1589.

Here I spend the day enjoying a little light which comes in through a lattice so that I can write, read and so on... All I can do is to encourage the Christians with letters and messages although they believe that I have left for the nearby islands. As a whole, they seem to be of good cheer. God only knows what they will do when the wolves turn their attention to them. 81

According to Gianbattista Porro, in 1628, a group of Christians exiled from Nagasaki to Edo had the good luck to be protected by the "old shogun" Hidetada. On the other hand a Dominican and a Franciscan together with many other Christians were burned at the stake. 82

THE HEIGHT OF PERSECUTION

According to Pedro Morejón writing in 1631, the maximum efforts of the persecutions were felt in 1629 and 1630, even in the northern areas of Dewa. 83 However the remaining years of Iemitsu's reign were even harsher. 84

The Japanese Matsuda Miguel Pineda died in 1633 three days after having been evicted by his landlord, 85, and in the following year only six Jesuits, two Dominicans and two Franciscans were left in Japan. 86

Cristóbal Ferreira, the Vice Provincial also remained but he was dismissed from the Society ipso facto on account of his renunciation of the faith during his martyrdom and when Manuel Dias, the Visitor, wanted to go to Japan from Macau in 1635 in order to stamp out the scandal, he was unable to do so. 87

By 1636 there were only five Jesuits left: Gianbattista Porro the Principal and Shikimi Martino, Yuki Diogo, Kasui Pedro and Konishi Mancio, the latter four being authorized to successively replace Porro in the position, should he die. 88

On the 4th of August 1639 a new edict was issued which closed all ports to Portuguese vessels, threatening those who dared to disregard this order with severe punishment. 89 The threats were carried out the following year when a legation from Macau arrived in Japan. The four legates and the fifty seven members of their entourage were sentenced to death on the 13th of August 1640, only thirteen oarsmen having been forgiven, one of them being Miguel Carvalho, the Korean, who was ordered by the shogun to return to Macau in a small boat in order to report what had happened. 90

1642 and 1643 were the years during which the suicide expeditions were organized under Antonio Rubino. The ten Jesuits and the various lay brothers who volunteered were the last missionaries about whose martyrdom there is accurate information. 91

THE VIEW FROM MACAU

Even so, the Jesuits in Macau did not lose hope. They still received news even though Japan was closed not only to its own countrymen but to foreigners. In 1648, they learned that Iemitsu, the shogun, was ill, "weak in the head" according to the gossips; that new silver mines had been discovered; that the Dutch and the Chinese were going to Nagasaki; that Japan refused to allow admittance to an Embassy that Dom João IV had sent from Portugal. 92 Out of the Christians, they learned that Francisco Cassola and Pedro Marques were still alive93 and that over two thousand Japanese had been expatriated. 94 The news that Il tono di Nangasachi ha prohibito a gli olandesi allevar colombe, por dubitar ch'adorino lo Spirito Santo rapresentato nella columba (The authorities in Nagasaki have forbidden the Dutch to transport doves because they imagine that they are worshipping the Holy Spirit represented by the dove) was little more than comical. 95

In 1647, the Jesuits in Macau wanted to make the most of a Chinese legation to Japan in order to seek help against the Tartars, but neither the Chinese nor the Jesuits achieved anything96 The political situation was quite clear and the Jesuit chronicler gives a summary in 1652 reporting the death of the Emperor, his under-age successor, palace mutinies, over three thousand casualties, and so on. 97

Vittorio Ricci, the Dominican provincial of China, received news from Japan every year, and they always referred to martyrs and the heroic deeds of the Christians who had remained loyal to their faith and who had also been responsible for spreading it. There were quite large congregations in various places, and near Kyoto there was a city full of Christians whom the Japanese 'kings' did not dare to attack.

Pedro Valladares, the old Portuguese who had been living in Japan for many years, handed the Jesuit Pedro Possevino a long report of the causes of the persecution on the 19th of May 1656. 98 The following year the Japanese Sosuke Miguel sent a letter from Japan to Siam speaking of the imprisonment of ninety six Christians who had been discovered in Omura and the execution of eight hundred and thirty pagans who had not denounced them. 99

MERCHANTS, APOSTATES AND MARTYRS

The demand for efumi from overseas merchants was revoked in 1660. 100 During this year there was such a shortage in Nagasaki that men began to sell their wives and children. When the Emperor learned of this, he despatched a series of ships carrying supplies for the starving and silver to release the captives, ordering that the Governor should be beheaded for his tyranny at such a time. 101 Such compassion was little more than fictitious because that year 103 martyrs died in Nagasaki, including various eight and nine year old children who were tied to their mothers' crosses, and also some samurais. 102

In 1661, there were eighteen martyrs some of them being crucified and others beheaded103 but according to Stanislao Torrente, some Dutch eyewitnesses told him that 1663 was a memorable year because 350 Christians were martyred. 104

People in Europe also learned that the "Pax Tokugawa" had been broken in Kyushu when the supporters of the Higo (Kumamoto) and Satsuma (Kagoshima) daimyos105, clashed ferociously in a war that could only be stamped out through imperial intervention. 106

In 1664 in Nagasaki, there was an outbreak of fire as a result of which only one road out of a total of seventy remained intact, this being considered to be a sign of the Wrath of Heaven. In the same year and in the same city, several nobles were martyred, the total being about thirty. 107

A CARMELITE AND A JESUIT IN JAPAN

In 1672, Italy learned of l'appertura nuova del Giappone, il cui avviso ci ha tutti colmato di sí gran consolazione (the new opening in Japan, a message which was received with great rejoicing)108 but in point of fact this was excessively optimistic. Even so, on the 10th of November 1679, Mattheus Souterman, the Rector of the Jesuit College in Gorizia wrote to a Carmelite nun saying that he had learned that one of her sisters who had just returned to Europe, passed through that region [Japonia] and reported that she had met there with one of our priests who had been hidden by certain barbarians... and that he had remained for the salvation of that people. 109

One month later, whilst still in Coimbra, Antoine Thomas and Adam Weidenfeld decided to volunteer for this undertaking. 110 In this they were following in the footsteps of Ferdinand Verbieste and others but they never managed to land in Japan. A Franciscan and an Augustine did manage to arrive in 1681 in a Dutch ship. They were disguised as businessmen but they were subsequently betrayed by the Dutch and handed over to the shogun. 111

MORE VOLUNTEERS

The unhappy tidings received from Japan each year did not undermine the enthusiasm of the Continental missionaries nor the numerous Jesuit volunteers from Europe. This has been recorded in various unpublished records.

New hopes were fanned in Macau and China when they learned that another Japanese legation would arrive in Peking in 1684 or 1685. 112 In point of fact, the Emperor agreed to bring back the old custom of welcoming an embassy from Japan in Peking every three years provided that they travelled in only three vessels. However, neither Francisco Noel nor any other Jesuits could set foot on the islands. 113 Isidoro Luci did not even manage it ten years later. 114

The reasons or lack of same for the anti-Christian persecutions in Japan did not make sense to China and in 1701, the emperor sent a mandarin, of imperial blood, to investigate why they had been expelled, but he only managed to confirm the status quo. 115

Luis Gonzaga, the Jesuit scientist, posted to the court at Peking, was still in Goa in 1707 and offered in vain to go incognito to Japan. 116 In his place the Sicilian priest Giovanni B. Sidotti, succeeded - like the Franciscan and the Augustinian in 1581 - but he had no sooner arrived on the island of Yakushima than he was arrested on the 13th of October 1708 and died imprisoned inhumanely in Edo (Tokyo) on the 15th of December 1715. 117

In 1732 Manuel d'Abreu informed the General Francisco Retz that he was prepared to enter Japan in 1736. 118 One year later, two Chinese were admitted to the province of Japan in order to penetrate through Korea. 119 One of them who was already a Jesuit may have been sent between 1753 and 1755 disguised as a merchant. 120

In 1773, the Jesuit missions that were flourishing throughout the whole of East Asia suffered a severe blow, which was carefully planned by the Jansenist heresy, that had even managed to infiltrate important offices in the Vatican. Pope Clement XIV's decision to abolish the Society of Jesus put an end to their efforts to obtain freedom for the religious community in Japan, which had been martyred from 1612 to 1873.

NOTES

1 The martyrs of this period correspond to the following villages: Kaga 5, Tsu 6, Toyana 7, Fukuyama 7, Matsuyama 8, Koriyama 9, Nara 9, Himeji 9, Matsue 10, Ueno 11, Iga 11, Takamatsu 14, Tokushima 14, Okayama 18, Hiroshima 40, Tsuwano 41, Kochi 42, Hagi 43, Tottori 45, Kagoshima 53, Nagoya 82, Wakayama 96, Kanazawa 104. See Shinko no Ishizue. Urakami shinto sor yuhai 100 shunen kinen. Ed. Jikko Iinkai (Nagasaki 1969).

2 I use the word "officially" because Japanese society continued to discriminate against Catholics up until the middle of the twentieth century, due mainly to the aggressiveness of the Protestant religions and above all the Baptists.

3 For the history of the first ten years of Christianity in Japan, see RDM Documentos del Japón 1547-1557 (hereinafter referred to as D J1), vol. 137 of the series Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu, Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Rome, 1990.

4 Those who went [to Japan] were severely persecuted, because they were opposed to all the other sects and had to speak openly, pointing out the errors of the bonzes' ways and habits in their endeavours to obtain money from the common people... They faced all sorts of difficulties and for this and other reasons, they were subject to severe persecution. (DJ1, doc. 57 §6-7).

5 The young Feudal Prince Otomo Yoshishige's positive approach to Xavier and Baltazar Gago did not prevent the people of Funai, incited by the bonzes, from launching violent attacks against the foreign missionaries, forcing them to fortify their missions for safety. Gaspar Vilela was banished from Hirado in 1558.

6 Third parties were responsible for arranging the first meeting between this national hero and the Jesuits. As a result Father Luís Fróis and Brother Lorenzo de Hirado managed to convince Nobunaga to give back their residence in Kyoto. RDM Origins of the Catholic Church of Korea from 1566 to 1784 according to unpublished documents of the period (English edition to be published by the Royal Asiatic Society, Seoul, quoted in RDM Origins), 9: "Oda Nobunaga dreams of Korea".

7 Francesco Pasio 4 Oct. 1587, ARSI (Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Rome) Japonica-Sinica, 10. II.275 (henceforth referred to as Jap.-Sin. followed by codex number).

8 Nobunaga was influential in causing several members of the Oda family to become Christians, but according to Valignano (7th Oct. 1581, Jap.-Sin., 9.1.37v) he forbade them to be unfaithful to their spouses.

9 Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598): he often changed his name and titles. Nowadays, in Japan, he is known as Hideyoshi belonging to the Toyotomi family, which disappeared in the early years of the seventeenth century. Fróis gives a great deal of biographical detail in his História de Japam (Lisbon 1976-1984) I-V. Brief but detailed biographies of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi can be found in Papinot, E: Histórical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan. (Tokyo 1982; henceforth Papinot).

10 Fróis, op. cit., V, 212.

11 The rise of this exemplary Christian amongst the nobility of the capital roused Hideyoshi's suspicions and caused him to issue an edict expelling the Jesuits in 1587.

12 Ryosai Lorenzo (c. 1525-1592): from Shiraishi, a village on the island of Hirado. In his youth he had been an itinerant troubadour playing the biwa hoshi (lute), a profession that was highly regarded in Japanese society. It was mainly undertaken by the blind or semi-blind such as Lorenzo. Baptized by Xavier in Yamaguchi in 1551, he took up residence with the missionaries. He was accepted into the Order at Funai c. 1556. (DJ1. doc. 109).

13 Organtino Soldo, alias O. Gnecchi Soldo (1532-1609): an Italian Jesuit who is almost always referred to by his baptismal name, signed his correspondence as Organtino Soldo, omitting his surname. He lived in Japan from 1570 until his death.

14 Alias Kuroda Yoshitaka.

15 Although he was opposed to the Church, on the advice of his uncles Kikkawa Motoharu and Kobayakawa Takakage, Mori Terumuto granted Kodera's petition and accepted the Jesuits in Yamaguchi (Fróis, 7th Oct. 1586. Jap.-Sin. 10. II.169.). None of the three houses lasted very long because the Jesuits were banished by the edict of 1587. Two important benefactors of the Mission, Omura Sumitada and Otomo Sorin, died the same year.

16 Fróis, 1st Jan. 1587, Jap.-Sin. 10. II.161v. Organtino accused Coelho of being indiscreet, Jap.-Sin. 11. I.70v. Kodera, the commander-in-chief, brought the island of Shikoku under Hideyoshi's yoke.

17 Under Kodera's command, Hideyoshi's army arrived at the precise moment that the novitiate and the college of Funai had escaped by sea after being besieged in the castle of Usuki in December 1586. They took refuge in the Yamaguchi residence that had only then begun to be rebuilt.

18 Antonino Prenestino, 20th June 1587, Jap.-Sin. 10.11.263.

19 Pedro Gomes points out that on the 20th of July Hideyoshi fooled them and that they only became aware of this on the 25th of the same month (Gomes, 28th Sept. 1587, Jap.-Sin. 10. II.264. For his part, Pasio, Fróis and Coelho thought that Hideyoshi had been acting hypocritically for some time past (Pasio, 4th Oct. 1587, Jap.-Sin. 10. II.275).

20 Authors have put forward a thousand reasons, occasions and motives to explain the sudden decision taken by the highly complex Hideyoshi. Organtino believed that he was motivated by his ambition to control the port of Nagasaki (28th Mar. 1607, Jap.-Sin. 14. II.278). Valignano, on the other hand suggests that the decree was the result of Hideyoshi's fury fired by the degenerate bonze Tokuun Yakuin, in letting people see that he had been unable to recruit young Christian girls for his master's harem (10th Oct.1590, Jap.-Sin. 11. II.227, and the 9th Oct. 91, ibid 245). According to Antonino Prenestino, Tokuun Yakuin added fuel to Hideyoshi's hatred for Takayama Ukon (10th Oct. 1587, Jap.-Sin. 10. II.279cv). José Luis Alvarez-Taladriz (henceforth TAL) refers to Hideyoshi's envy of Coelho's "fleet of small vessels" (TAL, Alejandro Valignano - Sumário del Japón, p. 145). To a certain extent, they are all right, but when all is said and done, the main cause must have been Hideyoshi's obsession with overcoming his inferiority complex -even if this is described by some other name- so that his pride and suspicious nature led him to make many mistakes and issue inexcusable edicts.

21 Diego Pacheco, "Guión histórico de la cristiandad de Satsuma" in Boletim de la Asociación Española de Orientalistas (Madrid 1974), p. 32.

22 On the 21st of February 1599, Bishop Cerqueira wrote that 137 houses and churches had been destroyed (Jap.-Sin. 20. II.57). In 1603 (Nagasaki, 12th January Jap.-Sin. 20. II.153) the Church's losses as a result of Hideyoshi's persecutions and those of his vassal Kato Kiyomasa, in the fiefdom of Higo could be listed as follows:

1. 1587: The Funai College and the Usuki Novitiate were sacked: 14 or 15 houses and 70 churches destroyed.

2. 1598: The college, the Novitiate, the Seminary and the houses in Arima and Omura destroyed together with 54 churches.

3.1600:6 or 7 houses and 87 churches destroyed in Higo and Amakusa.

23 Fróis, op. cit., V. 371.

24 Between 1595 and 1598, Pedro Gomes, the Vice-Provincial, sent some twenty Jesuits to Macau to continue their studies, and some of them to take holy orders. This move was designed to show the Civil Authorities that he was complying with the edict of banishment.

25 João Rodrigues Tçuzzu, a Portuguese Jesuit from Sernancelhe, was the official interpreter (tsuji, tsuzu) to Hideyoshi. He is sometimes referred to as Tçucçu, Tzuzu or Tçuzu.

26 Consecrated Bishop of Japan in 1592.

27 Pius IX canonized these 26 martyrs on the 8th June 1862.

28 A new decree was sent to Terazawa Masanari Agustín, the Governor of Nagasaki dated the 20th (or 24th) March 1597 (Jap.-Sin., 53.143v) Schütte Introductio ad Historiam Societatis Jesu in Japoniam (Rome 1968, cit. "Introductio"), p. 734; RDM Origins, 14 "Other Jesuits in Korea - Francisco de Laguna and Tamura Roman".

29 Called Gotairo. V. Papinot, op. cit., p. 129.

30 This started in May 1592 and the last Japanese soldiers returned in January 1599. RDM Origins, 13 "The first Jesuits in Korea", 14 "Other Jesuits in Korea - Francisco de Laguna and Tamura Roman".

31 According to Valignano, 20th Feb. 1599 (Jap.-Sin., 13. II.258v).

32 Jap.-Sin., 60.264v.

33 Francisco Vieira, 20th Oct. 1599 (Jap.-Sin., 13 11.325).

34 Throughout the estates of Kuroda Kanbyoe Simeon and his son Kuroda Nagamasa Damián (Kokura and Nakatsu, in northeast Kyushu) there had already been a considerable increase in Christian conversions that continued to grow. In 1600, this fiefdom passed into the hands of Hosokawa (Nagaoka) Tadaoki, who was married to Hosokawa Gracia and the father of several Christian children. After 1611 he became a cruel opponent of Christianity.

35 Kato Kiyomasa allowed Marco Ferraro's church to continue in return for the fruit that the priest sent him. (Jap.-Sin., 14. II.192)

36 Letter from Francesco Pasio dated 1604 (Jap.-Sin., 21.1.32)

37 Valignano, 15th and 16th Oct. 1601. (Jap.-Sin., 14.1.73 and 81v)

38 Schütte, "I1 primo annuncio della fede cristiana in Giappone" in La Civiltá Cattolica (Rome, 1981), vol. 1, p. 334.

39 Schütte, ibidem.

40 Mori Terumoto banished Navarro and a brother and again began to persecute the Christians: however the City Governor favoured them secretly and allowed them to retain their church and their residence (Valignano 1603, Jap.-Sin., 25.74)

41 There were six martyrs in Yatsushiro on the island of Kyushu: in 1603, two were beheaded and four crucified, among the latter a seven year old child. There was another martyr in 1605 in Yatsushiro and two in Suo (Yamaguchi) and one more in Satsuma in 1608.

42 Marco Ferraro to Aquaviva, Macau 21st Dec. 1614 (Jap.-Sin., 16. I.113). Hattori Pedrico died on the llth Jan when he was five years and two months old.

43 The first Provincial was Valentín Carvalho.

44 As early as 1609-1610, at the time of the dispute over André Pessoa's boat Nossa Senhora da Graça, on learning that some Portuguese had remained behind on land whereas others had escaped, leyasu ordered that they should all be killed and their estates confiscated and that all the members of the Society of Jesus should be banished from Japan. And, even after listening to the report that the vessel had been burned and that the Captain and the Portuguese had been killed, he again decreed that the priests should be banished from Japan (Schütte, Introductio, p. 191). However he finally gave in to the pleas of the Arima lord who begged to be allowed to continue trading with the Portuguese. However there was another reason for the flagrant persecution unleashed in Edo in 1612: The cause of this was a Franciscan friar by the name of Luis Sotelo. When the Lord of Japan destroyed his church which was in Yendo (Edo) he was ordered to go to Nagasaki. In spite of the fact that two other Friars had already left, he refused and, not only this, without having anything to do with the matter, he built a church near Yendo. The Governors learned of this from certain informers (who were angry with the Friar because of the stand that he took when they whipped a muleteer who had broken a keg of wine, which he had been transporting on the back of his mule). The Governors reported this to their Lord who was very upset and ordered that all those who had contributed silver to this factory should be killed; and thus six Christians were killed. After this there was a general outcry for the Christians to be sent back. Almost all of them went. 20 who refused to recant suffered horrible deaths as Christian martyrs. Such are the attitudes of these friars who have disturbed and caused trouble for the Christians. They ordered the Friar to move to Nova Espanha. According to what people say, Christianity has never been so besieged or suffered such restrictions that nobody wishes to be converted. (Porro, Osaka 28th Oct.1613, Jap.-Sin., 15. II.316).

45 Valentín Carvalho, March 1614. (Jap.-Sin., 15. II.323v). Schütte, Introductio 914 * Exilium praeconum Fidei.

46 Gabr. de Matos, Nagasaki 21st Mar. 1614. Jap.-Sin., 16. II.56v.

47 Valentín Carvalho, 19th Mar. 1614, Jap.-Sin., 16. II.42.

48 There were 114 Jesuits because Diego de Mesquita died a few days before the ships left. With regard to the diocesan clergy see Schütte, Textus Catalogorum Japoniae (vol. 111 of Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu (MHSI) (Rome, 1975) cit. Catalógos), p. 706 Nº 18.

49 Jerónimo Rodrigues, 22nd Dec. 1614. Jap.-Sin., 16.1.87.

50 According to Alfonso de Lucena, there were eight. See in Schütte Catálogos p. 559 and pp. 574-578 for a more detailed description of this exile in 1614.

51 The letters giving the dates of departure of the vessels have slight differences. See Schütte op. cit.,

52 Gaspar de Castro and two Jesuits only arrived in March the following year. See Schütte ibid.

53 Better known as the Blessed from Miyako. RDM Origins, 19. "The Korean Protomartyr, Hachikan Joaquin".

54 Dojuku: "Dôjuco. Young boys with shaven heads who serve the Bonzes in their villages". (Vocabulario, Nagasaki 1603). The Jesuits adopted the word to describe the young bachelors committed to completing their apostolate with the religious orders. Dojuku describes a state of life, whereas the term 'Catechist' describes a job or occupation. A woman can be a Catechist but never a dojuku. V. RDM "El neologismo «dujuku» - datos históricos" in the Records of the Congress on Portugal and Japan in the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries, Cologne 29 Jan - 3 Feb. 1991.

55 Jerónimo Rodrigues, 2nd Mar. 1615 (Jap.-Sin., 16.1.176).

56 Diego de Santa Catalina, Bartolomé de Burguilhos and the lay brother Juan de San Pablo.

57 Porro, 21st Jul. 1616. Jap.-Sin., 16. II.316.

58 Francisco Vieira, 6th Nov. 1617. Jap.-Sin., 17.105.

59 Cristóbal Ferreira 29th Dec 1617. Jap.-Sin., 17.116v. Tsugara is in the north of Japan.

60 Couros, 8th Oct. 1618. Jap.-Sin., 35.84. "The Shaven Heads" was the term used to describe laymen who were devoted to the services of the bonzes themselves.

61 Francisco Vieira, 22nd Sep. 1618. Jap.-Sin., 17.158 and 15th Feb. 1619 Jap.-Sin., 17.239.

62 Porro, 2nd Feb. 1620. Jap.-Sin., 17.629v.

63 Rodrigues Giram, 10th Jan. 1618, Jap.-Sin., 17.126.

64 Couros, 25th Feb. 1618. Jap.-Sin., 35.77.

65 Couros, 25th Feb. 1618 (Jap.-Sin., 35.81). On the 20th Jan. 1619, Juan Rodrigues wrote that the Governor of Nagasaki was hiding four or five priests who had escaped to Arima, Chikugo, Higo, Hyuga and Amakusa (Jap.-Sin., 17.222).

66 Francisco Pacheco, 5th Mar. 1618, Jap.-Sin., 36.114

67 Couros, 15th Sep. 1619, Jap.-Sin., 35.102.

68 Couros, 20th Mar. 1620, Jap.-Sin., 35.140.

69 Schütte, Introductio, pp. 348-366.

70 According to Couros, 15th Mar. 1621. Jap.-Sin., 37.180v

71 Vieira, 13th Feb. 1619, Jap.-Sin., 17.234.

72 Vieira, 15th Feb. 1619, Jap.-Sin., 17.238v; 30 silver coins for the informers, Navarro, 29th Sep. 1621. Jap.-Sin., 36.65.

73 Couros, 16th Mar. 1621, Jap.-Sin., 37.199v.

74 Couros, 28th Sep. 1621, Jap.-Sin., 37.203v.

75 Arch. Postulación de la Compañía de Jesús, Rome, Copia Publica Transumpti Processus... Sebastiani Vieira, pp 82v, 91 etc.

76 Jerónimo Rodrigues, 10th Dec. 1624, Jap.-Sin., 18. I.42; Couros, 20th Feb. 1625, Jap.-Sin., 37.225.

77 Porro, 15th Oct. 1624, Jap.-Sin., 18. I.38v.

78 Couros, 24th Feb. 1626, Jap.-Sin., 37.233.

79 Couros, 5th Oct. 1626, Jap.-Sin., 37.238. However, in some areas it was enough to not display any religious signs in public.

80 Jap.-Sin., 63.81.

81 Jap.-Sin., 63.82. It has been said that civilly the Christians were reduced to a social condition termed "fourth class", eta, burakumin or some other expression which in Western languages would be equivalent to pariahs but nevertheless better than hinin (who are not people but ex-convicts and the like). This is just as much of an invention as the suggestion that this fourth class was comprised of Korean ex-prisoners of war or captives taken during the frequent raids that the Japanese pirates made along the coast of Korea, China and the peninsula of Indochina.

82 André Palmeira, Jap.-Sin., 161. II. 105. In 1621 Hidetada refused to return priests to Manilla or Macau for fear of losing trade (Pacheco, 13th Nov. 1622, Jap.-Sin., 38.127.

83 Letter dated 15th June 1631, Jap.-Sin., 18. I.97 and 104. Pedro Morejón, a native of Medina del Campo, (Valladolid) died in 1639.

84 Hidetada died in January 1632 but his son Iemitsu did not release the news until Nov. 4th 1632 (Benito Fernandes, 4th Nov. 1632, Jap.-Sin., 35.184). Iemetsu reigned from 1632 to 1651.

85 Palmeiro, 4th Jan. 1634, Jap.-Sin., 21. III.346.

86 Palmeiro, 20th Mar. 1634 Jap.-Sin., 18. I.145v.

87 Manuel Dias, 18th Jun. 1635, Jap.-Sin., 18. II.227.

88 Manuel Dias, 30th Jul. 1636, Jap.-Sin., 18. II.254. In point of fact Yuuki Diogo died in Omura on the 25th Feb 1636 and Kasui and Konishi died in 1639.

89 António Rubino, 2nd Nov. 1639, Jap.-Sin., 38 212.

90 Report of the death of the Legates by António Rubino, 30th Sep. 1640, Jap.-Sin., 38.226; see RDM Origins, 30 "Rubino, Amaral and the Korean Miguel Carvalho".

91 Voss, Gustav and Cielik, Hubert: Kirishito ki und Sayo Yoruku Japanische Dokumente zur Missionsgeschichte des 17. Jahrhunderts (Tokyo, 1940) VIII-234. Vol.1 Monumenta Nipponica Monographs.

92 In January 1644, Jap.-Sin., 123.204v.

93 Francisco Furtado, 22nd Apr. 1647, Jap.-Sin., 123.156-7. Tongking, see Jap.-Sin., 22.340-346. Cassola died a martyr before November 1644, renouncing his involuntary Apostate and the news refers especially to Giuseppe Chiara, who died somewhat later under the same circumstances.

94 Annual letter of 1648, Jap.-Sin., 161. II.341.

95 Giovanni Filippo de Marini to General Vicente Carrafa, Tongking, 2nd May 1649, Jap.-Sin., 18.284 in the margin.

96 Jap.-Sin., 123.202. In Sept. 1652, Martino Martini bears witness to the report of an Austrian Lutheran called Henricus Frayentis [sic] whereby in 1650, the Jesuits heroically underwent torture almost every month in Edo prison. There were no more "apostates" in Japan apart from the ageing ex-Jesuit Cristóbal Ferreira (Jap.-Sin., 22.355) who was eventually martyred.

97 Jap.-Sin., 64.304.

98 Jap.-Sin., 29.351.

99 Jap.-Sin., 162.49.

100 Between 1665 and 1656, Christians were still forced to practice fumie - a test involving treading on a sacred fumie statue to prove they had renounced their faith. Jap.-Sin., 162.121-122; 125v; 128v. The truce over the fumie seems to have lasted until 1671 (see Juan B. Maldonado to General Juan Paulo Oliva, Macau 20th Dec. 1671, Pontifícia Univ. Gregoriana in Rome codex 292 570 67-8) but it was reintroduced in 1696 (Juan António de Arnedo, Jap.-Sin., 68.273) and it was still in force in 1716 (Jap.-Sin., 22.450).

101 Jap.-Sin., 124.46v.

102 Jap.-Sin., op. cit.

103 Jap.-Sin., ibid.

104 Jap.-Sin., 162.93-94. "A Dutchman whom I met with others in Fukien, a Chinese province, told me that on the eve of the Ascension in 1663, three hundred people in Nangazaqui were martyred, and it was said that in Japan there were more Christians now than there had been in times of peace, which could well be true if they were the children and grandchildren of those who had received Holy Baptism and been instructed in the mysteries of our blessed faith by their parents or grandparents." (Jap.-Sin., 64.402v)

105 The MSS definitely refers to Massamune.

106 Jap.-Sin., 124.46v.

107 Jap.-Sin., 64.402v.

108 In Sept. 1675, ARSI. Med, 33.323.

109 Mattheus Souterman, 10th Nov. 1679, Jap.-Sin., 19.87.

110 Waldenfeld, Coimbra, 18th Dec. 1679, (Jap.-Sin., 19). Antoine Thomas was called to the China mission. Being in Coimbra, the General of the Society managed to change his routing to the fortress-like Japan, but the undertaking was called off. (Jap.-Sin., 103.225v).

111 Jap.-Sin., 163.139. Fifty years earlier, there had been a similar experience with a Dominican and an Augustine. Jap.-Sin., 19.174.

112 Miguel Vaz, Macau 21st Nov. 1684, Jap.-Sin., 163.253

113 François Noel, Canton, 13th Oct. 1685, Jap.-Sin., 163.304.

114 Isidoro Lucci, 3rd Nov. 1694, Jap.-Sin., 82.388 and 392.

115 Antoine Thomas to the Jesuits in the China Vice Province, Peking 17th Dec. 1701, Jap.-Sin., 167.217. In 1692, Emperor K'ang Hi published an edict in favour of the Catholic Church, but prior to 1711, he did not allow a church to be built in Shengyang, the capital next to Korea. See RDM Origins, Chronology 1692 and 1711.

116 Goa 14th May 1707, Jap.-Sin., 170.173.

117 RDM Origins, 38 "The Evangelization of Korea from International Waters".

118 Manuel de Abreu wrote to General Francisco Retz that he would go to Japan "post quadriennium". Macau 15th Dec. 1732, Jap.-Sin., 37.25. There is no record of his having entered Japan.

119 Not in the China Vice-Province (Jap.-Sin., 181.94).

120 Pontificia Univ. Gregoriana in Rome, cod. 292.595-607. Notizie delle Missioni Asiatiche 596.

*Historian, specialist in Japanese affairs (where he spent twenty seven years), particularly on matters concerning the Japan Mission. Since December 1981, he has been a member of the Historical Institute of the Society of Jesus in Rome.