THE ESTABLISHMENT AND GROWTH OF FOREIGN TRADE IN MACAU

In the past, Macau was one of the ports for the District of Heong San (as, for instance, the cities of Chong San and Zhuhai are today) and was no more than a little fishing town.

However, with the gradual development of foreign trade from the second half of the reign of Ka-Cheng (Ming Dynasty) onwards, the city quickly became the main shipping port for Canton Province and a trading post for Western and Oriental countries.

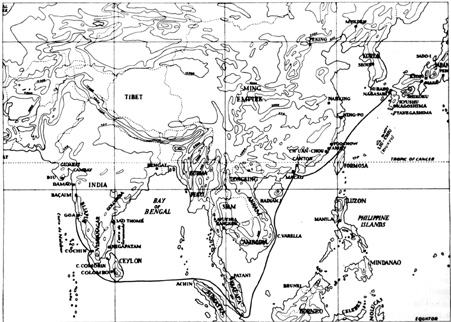

At that time there were three maritime trade routes: Macau-Goa-Lisbon; Macau-Nagasaki; and Macau-Manila-Mexico. We shall now take at a look at each of these routes individually.

The Macau-Goa-Lisbon Route

The Portuguese had conquered Goa in India in 1510 and went on to take a lease in Macau in the thirty second year of the reign of Ka-Cheng (1553). Portugal was thus able to establish trading between Macau and Goa, and from Goa on to Lisbon and other European countries.

The Portuguese merchants used massive ships to ply the maritime routes: each ship could hold between six and sixteen hundred tons of goods and five or six hundred people. They were able to take large quantities of costly items from China (via Macau and Goa) to Lisbon and from there to other parts of Europe.

The Chinese goods exported from Macau to Goa included raw silk, spun silk, satin, gold, copper, musk mercury, cinnabar, sugar, medicinal plants, bronze bracelets, camphor, porcelain, gilded beds and tables, Chinese ink, handkerchiefs, mosquito nets and golden necklaces. Nevertheless, the main item which was traded was unwoven silk. According to statistics taken between 1580 and 1590 (Ming Dynasty) each year three thousand piculs (each picul weighed more or less fifty kilos) of unwoven silk were sent from Macau to Goa. This alone was worth two hundred and forty thousand taels of silver ingots. In 1635, six thousand piculs of unwoven silk were sent, amounting to four hundred and eighty taels of silver ingots. (1)

In the other direction, the Portuguese were bringing silver, pepper, ebony, ivory and sandal wood from Goa to Macau. Silver was Macau's main import item. Between 1585 and 1591 nine hundred thousand taels of silver ingots arrived in Macau via Goa. (2)This was Peruvian silver but it did not reach its destination directly. It was taken to Europe by the Spanish and the Portuguese and then brought to Macau via Goa.

In 1609, the thirty seventh year of the reign of Man Lek, a merchant from Madrid with twenty five years of experience in imports and exports in the Orient wrote: " almost all of the silver which the Portuguese brought from Goa to Macau was taken to China".(3)

In 1631, the fourth year of Son Cheng (the last reign in the dynasty), the Portuguese in India were attacked by the Dutch. The latter occupied Malacca and their fleet took control of the main sailing routes between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. This led to the discontinuation of shipping between Macau and Goa and the expulsion of the Portuguese.

The Dutch gained control of trade and transport in this part of Asia and the authority which the Portuguese had held in this was substituted by the Dutch with a subsequent weakening in trade relations between Macau and Lisbon.

The Macau-Nagasaki Route

In the reign of Ka-Cheng (Ming Dynasty), the government forbade the Chinese population to trade with Japan because of the Japanese invasion which had much disadvantaged China.

However, the Portuguese in Macau were not included in this prohibition and they continued to be able to trade with the Japanese. Thus trade between Macau and Nagasaki began to develop. A great variety of items were exported: white silk, lead, rosewood, gold, mercury, tin, sugar, musk, medicinal plants, liquorice root, cotton thread and cloths, and so on. For example, in 1600 a Portuguese ship took five or six hundred piculs of white silk, five hundred piculs of lead, three to four thousand taels of gold, one hundred and fifty to two hundred and fifty piculs of mercury, two piculs of amber, five or six hundred piculs of tin, two hundred and ten to two hundred and seventy piculs of sugar, two to three hundred piculs of cotton threads, three thousand metres of cotton cloth, five or six hundred piculs of medicinal plants, seven hundred piculs of rhubarb, one hundred and fifty piculs of liquorice root, and seventeen hundred to two thousand pieces of high quality silk totalling one hundred and thirty seven thousand, six hundred taels of silver ingots. (4)Out of the thirteen items, the white silk was the most valuable.

According to statistics from the reign of Son Cheng, the Chinese goods exported from Macau to Nagasaki had an annual value of over one million taels of silver ingots. (5)There was one year in which trade was worth over three million taels of silver ingots. (6)White silk continued to be the most important component in the export trade. For example, in 1635, (the eighth year of the reign of Son Cheng), one thousand, four hundred and sixty piculs of white silk worth one million four hundred and seventy thousand taels of silver were exported to Nagasaki. (7)

In the opposite direction, the main item which Macau imported from Nagasaki was silver. In 1586, Chou Yuan Wei wrote: "The port in the district of Heong San (Macau) is the key element in the loading and unloading of goods: each cargo usually brings a fortune in gold and other precious things, and can be as much as several tens of thousands".(8)

Sometimes they only brought silver as Kwu Yim Mou was to note: "The ship crosses the ocean... on its way from Japan... and brings no merchandise, but only gold and silver".(9)

According to foreign documents, fourteen million, eight hundred and ninety nine thousand taels of silver entered Macau during the forty five years lasting from 1585 until 1630 (the thirteenth year of Man Lek's reign until the third of Son Cheng's). This gave an annual average of over three hundred and thirty thousand taels. (10)

This money entered China through Macau and was converted into merchandise in Canton before returning to Nagasaki. Consequently, Sino-Japanese trade developed through the Macau-Nagasaki route which became extremely prosperous. In the tenth year of the reign of Son Cheng, (1637), the Japanese Christians rebelled through involvement with the Portuguese Jesuits. In late 1639 the Japanese emperor expelled all Portuguese living in the country. (11)

In 1640 an official decree was published, forbidding any Portuguese from trading with Nagasaki and as a result trade with the city decreased. It did not stop altogether, however, as the imperial decree only denied the Portuguese the right to come and trade but did not prevent the entrance of other nationalities, namely the Chinese, and the Dutch.

The Chinese were given preferential treatment in trading in Nagasaki: merchants and also sailors were allowed to come ashore and do business.

The Portuguese used the facilities given to the Chinese to carry on a secret trade with Nagasaki. This is why maritime trade between Macau and Nagasaki was not altogether suspended during the last reign of the Ming Dynasty.

The Macau-Manila-Mexico Route

This was another of the principal trade routes for Macau's foreign trade. The goods taken to Manila included raw silk, cloths, cotton cloths, satin, taffeta threads, tulle, mosquito nets, pearls, precious stones, saphires, jade, artificial flowers, jujubes, musk, figs, chestnuts, peanuts, pomegranites, pears, oranges, preserved pork, salted meat, saltpetre, sugar, ceramics, pots, iron, copper, tin, mercury, aluminium, washtubs, ammunition, bullets, Chinese ink and so on.

The quantities which were exported were enormous. Following the third year of the reign of Son Cheng, the total value of exports from Macau to Manila was around one and a half million Spanish duros(12), equivalent to a million taels of silver. Raw silk and the other cloths were the most important items.

The Bishop of Manila, Salazar, observed that: "Boats come from Macau bringing natural products to do business... Other than the foodstuffs, most of the items are textiles (black satin, embroidered in gold and silver) and various padded cotton garments (black and white) ".(13)

Prior to the reign of Son Cheng, in 1608, the value of Macau's exports to Manila was two hundred thousand duros, of which 95% was textiles. (14)

From 1619 onwards, trade in textiles between China and Manila was almost completely monopolized by the Portuguese and they made tremendous profits from their transactions. In 1635, an Englishman who was visiting Macau recorded that the Portuguese made a 100% profit on each shipment to Manila. (15)

After arriving in Manila, the raw silk was taken to the northern part of the city where the Chinese merchants lived, for it to be resold. The area was known as the "Silk Market", a reflection of how important silk was in commercial transactions between Macau and Manila.

Between 1587 and 1640, Manila exported twenty million, five hundred thousand silver duros to Macau. This amounted to 68.9% of Manila's total silver exports. (16)

During the same period, Manila also exported twenty nine thousand, four hundred thousand silver duros to China but this was silver from Peru and Mexico, not the Philippines. The Spaniards had control of the trade and used Manila as the link between Macau and Mexico. Besides silver, other products coming from Mexico by way of Manila were ebony, refined cotton, wax and cobalt.

The articles produced in the Middle Kingdom and transported to the Philippines for export to Mexico were mainly silks and satins, cloths, padded clothing, mantillas, porcelain and faiance, fans, cinnamon, ironware, copper, musk, gold, wax, diamonds, jewels, pearls, carpets and so on.

Silk and other textiles were the most popular items in business between the Philippines and Mexico.

Before the ninth year of the reign of Son Cheng (1636), each ship sailing to Mexico had three to five hundred boxes of textiles on board. On one occasion there were two ships, one of which carried a thousand boxes and the other twelve hundred. (17)

Most of the raw silk was sent to factories in Mexico to be woven and then to Peru to be sold. The Spaniards made huge profits ranging from one hundred to three hundred per cent on their textile transactions.

Mexico's exports to the Philippines were, at first, velvet, satin, taffeta, cloths, hats, shoes and stockings made in Spain. Also wine, vinegar, olive oil, preserved meats, ebony, raisins, and sisal cloth made in France and Holland. (18)

The prices paid for these goods was extortionate, however, and the Chinese goods which came at very competitive prices and were of a high quality gradually began to dominate the market. Eventually, only wine, olive oil and silver were imported into the Philippines from Mexico and it was mostly silver that Philippine merchants sought. From 1596 to 1634, over twenty six million duros worth of silver was imported into the Philippines. (19)Nevertheless, a great deal of that silver reached China and Macau because the Spaniards bought Chinese goods in Manila.

76.5% of the Mexican silver imported into the Philippines at that time went to Macau and was worth twenty million Spanish duros. (20)This constituted 79% of the silver which the Middle Kingdom bought in a business which was worth twenty five million Spanish duros. (21)

This illustrates how the Mexican silver, which was sent to the Philippines in the late Ming Dynasty, was basically destined to reach China via Macau and reflects a healthy level of trade between Macau, Manila and Mexico.

All the above points indicate that foreign trade really took off in the first hundred years after the establishment of Macau (in 1553). In the XⅥth and XⅦth centuries it was recognized as an international trading centre and transit port. The city continued to progress from a small town to a flourishing city. As one Chinese historian noted "Tall buildings stand, one in front of the other... the settlement of hundreds of houses is growing to more than one thousand!".(22)Macau attracted Chinese merchants and foreign investors to settle in the city and so the population went on increasing.

According to historical sources, in the thirty sixth year of Ka-Cheng's reign (1557), Macau had a population of only four hundred. In 1563 it grew to five thousand, of whom four thousand one hundred were Chinese and nine hundred Portuguese. In 1578 (the eight year of the reign of Man Lek) the population stood at around ten thousand and had grown to over forty thousand by 1640, the thirteenth year of the reign of Son Cheng, the last reign in the Ming Dynasty. (23)

REASONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MACAU'S FOREIGN TRADE

We shall now examine why Macau was able to develop its foreign trade so rapidly.

First Reason

The Chinese feudal economy was quite highly developed from the middle of the Ming Dynasty onwards.

At this point, the Chinese economy started a new phase by making its industries more specialized. This led to an increase in production and higher inflation.

In many areas of the country (mainly in the coastal regions of South East China), new manufacturing industries appeared. In Chiang Su, the weaving of cotton cloth came to be the main activity of the inhabitants of villages and cities. Each year, huge quantities of cotton were produced for export to other provinces and countries.

In Suchow and Hangchow (both cities) the art of weaving silk had been known for a long time, and at this point, many other towns involved in this industry sprang up, such as Seong Lam, Pok Yuen, Kong Keng, Chan Jak and Sen Jak. Each of these settlements housed seven to twelve thousand people who spent their lives weaving silk, satin and cotton.

In addition to Jiang Su Province, the cloth from Canton and Fukien provinces was also renowned for its high quality. The Chinese ceramics industry was also famed for its excellent products and ceramic products from Jiang Si, Canton, Fukien and Zhejiang provinces were exported.

Unrefined and crystallized sugar was produced in Canton and Szechuan provinces and sold to Japan, the Philippines and Java.

The mining industry grew very quickly in Canton and Fukien, and metal tools and products were exported all over the world.

At the same time, the manufacture of pottery, paper and furniture was beginning to take shape. Commercial agriculture, particularly the cultivation of natural foods, was also promoted in Suchow, Zhejiang, Peking and Canton and fruit farming was a lucrative industry in Canton, Szechuan, Hainan and Hupei.

In the Pearl River Delta, fishing, fruit farming and the cultivation of mulberry and sugar-cane plantations were the most important activities and provided an excellent source of items to be exported through Macau.

A Western author decribed the situation in the following way: "the Chinese have the best food in the world - rice, the best drink - tea, and the best cloth-cotton".(24)

Chinese products were already a familiar sight in Western countries. The social status of Spanish noblemen was reflected by the Chinese goods they possessed. There were also cheaper items from China which were eagerly bought by the Central American Indians and Blacks. It could thus be said that Chinese goods made a major contribution to the American, Philippine and European markets.

The discovery of the "New World" did not bring with it an immediate recognition of the potential of that new market. China continued to be a seemingly inexhaustable warehouse of all kinds of merchandise. China was trying to expand its own domestic market at the same time as it was trading abroad, in order to make the market more fluid. As Karl Marx pointed out, merchandise held in the hands of the producer has no immediate value, but for those who acquire the goods they are useful and so they must circulate for an exchange of products to take place. (25)

Before Macau becoming a centre for international trade, Chinese products were exported to Japan and other Asian countries but supply did not satisfy demand. Flourishing production during the Ming Dynasty thus contributed to Macau's economic development.

Second Reason

Macau's geographical position meant that it was in an excellent natural setting for its development.

Macau's situation as a peninsula means that it is bordered by the sea on three sides. Leaving Macau for the Northeast of China you could reach Shantow, Xiamen (Amoy), Ningpo, Shanghai, Tsingtao, Tianjin, Daling and Nagasaki in Japan. Going west from Macau would bring you to Goa, and via the Cape of Good Hope, to Europe. Going southwards would bring you to the Philippines. Macau's port lay to the South of the city and loading and unloading was carried out there. Macau had the added advantage of being near the Pearl River Delta, giving access to Sekei, Jianming, Fatsan and Canton. Further on, there were links with other branches of the Pearl River enabling even greater access and forming a favourable maritime network.

An historic document "Records of Macau" described Macau as being "joined on only one side to the mainland from where the cereals came; the rest is surrounded by sea giving rise to heavy maritime traffic of Chinese boats which could easily come to Macau and then set off on the high seas".(26)

Consequently, Chinese merchandise frequently came to Macau and was then shipped abroad and the same happened to foreign products which arrived in Macau and were then sent into all parts of China, making Macau a trading centre. We find the best proof of this in the book Poems about Macau: "Of all the ports in Canton, Macau is the most grandiose".(27)

Long before Hong Kong was established, Macau's priviledged conditions enabled it to promote its trade abroad.

Third Reason

The Japanese pirates were also making their contribution to Macau's foreign trade.

The university lecturer Tai Yoi Hoi, a specialist on Macau's history, believes that the Japanese pirates were not really "pirates" as they were described in history books published during the feudal period in China. They were rather "sea traders" who did business with the Chinese and other Asians at sea. While there was still no law forbidding these practices, these Japanese pirates were regarded as regular merchants, but when the Middle Kingdom prohibited foreign trade, they became "sea pirates" as they are now known. (28)

On their first voyage from Macau to Japan, the Portuguese went with a famous pirate called Wong Chek who was known as "Japanese pirate". In one part of Japan he "built Chinese-style houses and whole crews off the Chinese boats would go there frequently".(29)

The Japanese made Wong Chek their business agent and thanks to his fame he called himself "the King of Anhui" as he was a native of Anhui, China. He recruited and directed three thousand poor Japanese to trade illegally along the coast of Southeast China. He was later captured by a Chinese admiral in 1557 but his employees continued to work the coasts of Zhenjiang, Fukein and Canton.

The Portuguese also allowed these pirates to trade in Macau. They say that "the fu-lang-ji (foreigners) of Macau... contract the Japanese slaves as lackeys, and the outcasts as confidants".(30)This explains why the Portuguese had contacts with pirates in the past. At the time, there were only a few Portuguese living in Macau and this was why trading between Macau, Nagasaki, Goa and Manila was carried out via the "Japanese pirates".

Xie Shao Tze says that the Chinese also regarded the sea as land and searched for profits by trading with the Japanese whom they considered their neighbours. (31)

Fourth Reason

The Emperor of the Ming Dynasty was more interested as a feudal lord in agriculture than in trading.

The emperor also actively discouraged trading between the Middle Kingdom and other countries, continuing a traditional approach which had been prevalent for thousands of years. The "law of the great Ming Dynasty" did not allow any contact via the sea between the population and foreigners and only Canton was allowed to carry on trade with foreigners. Consequently, Macau took advantage of this to develop its own foreign trade in conjunction with Canton.

INFLUENCES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF MACAU'S FOREIGN TRADE

Influences on China

China had been starting a new economic and social régime during this period of development in Macau's foreign trade. What this amounted to, more precisely, was the transition from a feudal economy to capitalism.

A large amount of silver was coming into China via Macau at the time and the buyers were interested in Chinese products leading to a growth in Chinese exports. An increase in the quantity of cotton being exported each year to the Philippines stimulated the cultivation of cotton and led to an increased number of cotton mills.

Before 1342, fifty kilos of rice cost less than one tael. By 1638, they cost almost two taels and after 1642 the price stood at around two to three taels. This situation was due to the influx of silver into China. (32)As well as rice, many other goods also became more expensive such as clothes, cloth, vegetables, silk, olive oil, salt, tea, paper and so on. At that time, the Cantonese used to say that all the inhabitants of Macau were wealthy. (33)

The Pearl River Delta entered into a new phase of economic development. Markets were set up near the cities, towns and villages, making this a prosperous area. In fact the largest fortunes in China were to be found in this southern region. Canton became increasingly wealthy and was the most flourishing city in China. (34)

Silver was used as currency in China and by the Ming Dynasty taxes could be paid in silver whereas previously they had been payable in food and goods.

Influences on Southeast Asian Countries

As trade between Macau and Manila and other Southeast Asian countries grew, the inhabitants of these countries were using an increasing number of modern Chinese tools in farming and the manufacturing industries. These tools were used particularly in extracting ores, tilling uncultivated land and in handcrafts. More important was the fact that many Chinese workers moved to these countries and devoted themselves to commerce, farming and manufacturing.

According to statistics, in the late Ming Dynasty thirty to forty thousand Chinese emigrated to the Philippines and twenty to thirty thousand to Java. Taking into account the numbers who emigrated to other places, there must have been over one hundred thousand emigrants. (35) Some Chinese emigrants worked in mining, reaping their wealth from the wilderness of the mountains. Others took on plantations and grew huge quantities of pepper and other products such as sugar-cane for refinement, and rice. Vast tracts of land were turned into rice paddies.

The Chinese took advanced production methods to the Southeast Asian countries and worked with the natives to transform uncultivated land into economically developed areas. A good example of this is what happened in the Philippines: Chinese emigrants already had advanced techniques in manufacturing and trading and when they implemented this in the Philippines the result was a rapid development in the economy. John Fayman stated that: "In fact, the Chinese were the first to give the natives any idea of productive labour in trade and industry. It was they who introduced to the Colony the process of extracting sugar using vertical grindstones and refining sugar by boiling it in vats".(36)

At the same time, the development in trade between Macau and the Southeast Asian countries meant that high quality Chinese products were constantly being exported at low prices to these countries, to the disadvantage of the local economy. In many places, the inhabitants gradually altered the structure of their economy to adjust to this change.

For example, in the Philippines everyone, regardless of whether they were a chief or a slave, worked in weaving cloths.

When the Spaniards started trading with Macau "each year at least eight ships came from China and some years brought twenty or thirty loaded with cottons and silks. When they saw the cloths brought by the Chinese, the inhabitants of the Archipelago and Punkac Jaya province left their weaving and started to wear Chinese cloths".(37)

Other merchandise was taken to Southeast Asian countries and this naturally gave rise to commercial transactions. At the time, merchants in Southeast Asia bought large quantities of local products in order to trade with China. This meant that there was a greater circulation of goods and consequently an increased use of coins. Many areas began to use Chinese gold, silver, copper and tin coins assiduously. For example, in Java, "Chinese copper coins dating from different periods were used".(38)In Palembang, "Chinese copper coins are used in the market as well as cloths".(39)

Influences on American Countries

In the late XⅥth century and early XⅦth century most of the American countries were Spanish colonies. Their social economy was comparatively backward with an under-developed manufacturing industry. As a result, the Indians and Blacks wore imported clothes and used imported household items most of which came from Spain. With the opening up of the Macau - Manila -Acapulco shipping route, however, Chinese merchandise could be taken to several American countries, particularly Mexico and Peru. Many Indians and Blacks began to wear Chinese silk and it was frequently used in the Indians' churches. (40)

In fact, importation of unwoven silk from China provided an important raw material for the textile industry in the region. An example of this was Puebla, a Mexican town, where weaving depended directly on raw silk. In a report presented to the king of Spain, Monfalcon said: "If the importation of raw silk were to be prohibited, the fourteen hundred inhabitants who live from weaving it would die ".(41)

At the same time, the importation of Chinese products was having a great influence on silver mining in Mexico. Mexico paid for the Chinese goods with silver and so a large amount of silver came into China through Macau. This in turn stimulated exploitation of and production in the Mexican silver mines. On the other hand, many of the Chinese products were cheap and resistant and satisfied the miners' most important needs. This allowed the silver mines to maintain and develop production.

Influences on Capitalist Countries in Western Europe

The late XⅥth century and the early XⅦth century was precisely the time when capitalist means of production were growing in Western countries and these countries were adopting new trading policies. "Mercantilism" valued trade with foreign countries most highly. According to Karl Marx, monetarism and mercantilism spring from the same source: wealth, world trade and those sectors of domestic industry which are related to world trade.(42)

Portugal rented and occupied Macau, and Spain invaded Manila and colonized America during the space of one hundred years. They controlled trading between Macau - Nagasaki, Macau - Goa - Lisbon, and Macau - Manila - Mexico, reaping enormous profits of one hundred to several hundred per cent. For example, between 1503 and 1650, the Spaniards took over one hundred and eighty thousand kilograms of gold and over sixteen million kilos of silver from Mexico, Peru and the other colonies. (43) Fortunes were taken back to the fatherland where they were transformed into powerful capital allowing the development of a capitalist economy in these countries. At the same time, they were trading with Macau and taking back home not only cheap and plentiful Chinese merchandise to enrich their domestic market, but also Chinese technology which was particularly advanced in the fields of the iron industry, the textile industry and ship building. The use of this technology was a major factor in the development of the capitalist economy.

Translated from the Portuguese by Marie Imelda Macleod

NOTES

(1)Boxer, C. R.

The Great Ship from Amacon, ed. ICM (1988), p. 182.

(2)Idem, ibidem, p.77.

(3)Idem, ibidem, p.195.

(4)Idem, ibidem, pp. 179-181 "Memorandum of the merchandise which the Great Ships of the Portuguese usually take from China to Japan".

(5) Idem, ibidem, p. 144.

(6)Idem, ibidem, p. 47.

(7)Idem, ibidem, p. 153.

(8)Xuanwei, Zhou

Chronicles of Jinglin, p.3.

(9)Yanwu, Gu

The Book of Good and Bad things in the Countries of the World, scroll 93.

(10)Boxer, C. R.

Idem, ibidem, p. 157.

(11)Chang, Tien-tse

Sino-Portuguese Trade from 1514 to 1644, Leyden (1934), pp.138-77.

(12)Boxer, C. R.

Idem, ibidem, p. 169.

(13)Jinge, Chen

The Chinese in the Philippines in the XⅥth Century, (1936) p. 67.

(14)Hansheng, Quan

A History of the Chinese Economy, ed. Xing Ya, vol. 1, p. 460.

(15)Boxer, C. R.

Idem ibidem, p. 7.

(16)Shine, Wang

The Development of Trade between China, Manila and Mexico in the Late Ming Dynasty, (1954).

(17)Hansheng Quan

Ob. cit. p. 465.

(18)Historical Documents on the Philippine Islands: scroll 6, pp. 50-52; scroll 10, p. 12; scroll 8, p. 84; scroll 12, p. 64; scroll 27, p.199.

(19)Same as above.

(20)Shine, Wang

Ibidem.

(21) Shine Wang

Ibidem.

(22)Tingyuan, Liu

History of Nahai District, scroll 12.

(23)Qichen, Huang and Kaisong,

Deng "Historical Development of the Inhabitants of Macau", Va Kio newspaper (9/6/85).

(24)Remer, C. F.

The Foreign Trade of China (1926).

(25)Marx, Karl

"Das Kapital"

(26)Guangren, Yin and Rulin, Zhang

Summarised Records of Macau, vol. 1.

(27)Same as above.

(28)Xiejie

The Occupation of Lu Tai by the Japanese.

(29)Motomiys, Yasuhiko

A History of Sino-Japanese Transport, vol. 2, p. 304.

(30)Archives of the Kingdom of Shenzong in the Ming Dynasty, scroll 576.

(31)Zhao Zhi, Xie

Wu Za Zhu, scroll 4.

(32)Records of Prices in the Ming Dynasty, (1959).

(33)Dajun, Qu

New Commentaries on Canton, scroll 2.

(34)"Canton", Huang Min Jing Shi Collection, scroll 342; Memories of Guo Gai, scroll 1.

(35)Weihua, Zhang

Brief Notes on Foreign Trade during the Ming Dynasty, (1955)p.105.

(36)Hansheng, Chen

Historic Documents About the Emigration of Chinese Workers, (1981), vol. 4, p. 50.

(37)Historical Documents on the Philippine Islands: scroll 6, pp. 50-52; scroll 10, p.12; scroll l8, p.84; scroll 12, p.64; scroll 27, p.199.

(38)Guan, Ma

Places of the World, Java, Palembang.

(39)Idem, ibidem.

(40)Historical Documents on the Philippine Islands: scroll 6, pp. 50-52; scroll 10, p.12; scroll 8, p. 84; scroll 12, p. 64; scroll 27, p.199.

(41)Historical Documents on the Philippine Islands: scroll 6, pp. 50-52; scroll 10, p. 12; scroll 8, p. 84; scroll 12, p. 64; scroll 27, p.199.

(42)Marx, Karl

A Critique of Political Economy.

(43)Qin, Yang Han

"Prosperity and Decline in sea trading between China and the West from XⅤth to the XⅦth centuries", No 5, Review of Historical Studies.

*Vice-Rector of Chong San University (Canton) and researcher on the History of Commerce in Macau.

**Assistant Head of the Department of Social Sciences (Canton) and researcher on the History of Commerce in Macau.

start p. 24

end p.