One of the results of a study made concerning the fishing industry on the island of Chang Chau (Hongkong) was that actual fishing only took up one hundred and twenty to one hundred and fifty days of each year. The rest of the time was divided between activities connected with cyclical festivals, ceremonies and other rites and religious events (So, 1964: pp. 144-45). In Kam Sai, a fishing village on an island off Hongkong's New Territories with a population of only a few hundred, the annual festival in honour of the patron deity of the local temple alone cost, in 1982, $120,000HK which had been collected through subscriptions and donations made by the participants themselves (Ward, 1982: p. 33).

Although there are no available statistics, it seems that there are also strong indications of a similar degree of importance given to religious activity in Macau. At any rate, the high incidence of temples is worth considering (1). There is hardly a corner of the city which is not graced with buildings, altars, alcoves and other ritual places which are a reflection of the position of religion in this society. Another obvious indication is that the most representative examples of traditional Chinese architecture are those buildings with a religious function. The financial burden which maintaining and preserving these buildings represents, especially in a society which has not always paid attention to the basic requirements of health, hygiene and education, could never have been supported by a community which was indifferent to religion. Furthermore, the obstacles which the local population has placed before the Administration when there have been attempts at urban expansion have usually been rooted in symbolic, and not concrete, causes. There are countless instances in which the removal of constructions, rocks, trees and other natural phenomena in the ground has been in conflict with the principles of geomancy (2). The most famous example of this is the incident which cost one governor his life (3).

Nevertheless, temples and other public places constitute only one of many kinds of religious expression. There are a large number of activities which take place in private. In homes one can find symbolic representations of the family's ancestors and many deities and these are the object of daily attentions. In private there is a myriad of ritualistic and religious beliefs related to births, marriages, deaths and so on. All of these are the product of continual consultation of the almanac (tung siu 通勝) which offers guidance on a countless number of daily activities such as travelling, moving house, etc..

Bearing in mind the fact that religion in Chinese society is of extreme importance, then we can almost assume that it will have even greater significance in the fishing population as they are famed for being the most superstitious social group. It has been said that their view of the world is, essentially, "religious" (Ward, 1955). It is obvious that the fisherman in the South of China operates according to a unique cosmological system which constantly adjusts itself according to the needs of an invisible but omnipresent world with which the fisherman can come into contact through certain rituals.

Hence, the fisherman organizes his activities and, in a broad sense, regulates his entire life in order to be in harmony with a world populated by spiritual forces, some of which are benevolent (san 神), some ominous (kuai 鬼), by the powers of the ancestors (chou sin 祖先) and by geomantic influences (fong soi 風水). These all add up to a collection of prohibitions which include certain beliefs about pollution and some kinds of "sacred" fish (san yu 神魚). This invisible world is said to be influenced by the fisherman through his observance of the various prohibitions and beliefs, including his attitude towards his family and those around him, through his respect for his ancestors, through his worshipping of the deities and through holding exorcisms and other rites which, in the case of the annual cyclical festivals, are public, collective events.

The points which have just been highlighted seem to indicate that it is important to consider the role of ritual and religion when building up a sociological picture of the fishing community in Macau (Brito Peixoto, 1987, 1988a, 1988b). The research which I have been carrying out in this area has been based on the fact that the fishermen of Southern China remain a socially distinct group, a distinction which has become their very "raison d'être" and in which religion plays a very large role.

The focus of the religious activity for the fishing community in Macau is Barra Temple (Ma Kok Miu 媽閣廟), the most significant reference point on land for them. The temple is located at the entrance to the Inner Harbour which serves as a shelter for the vast majority of fishermen in the Territory. It is dedicated to the goddess A Ma who is the patron deity of all sailors. The temple predates the arrival of the Portuguese who also used it as a reference point for the area, thus explaining the derivation of the name for the city itself (Batalha, 1987). The fact that this temple was seen as the symbol for religious activity in the area seems to suggest that it has long held an extremely important place in the lives of the inhabitants, a place which it holds to this day despite the fact that the course of five hundred years has made great changes in this region. Nowadays, Barra Temple still has pride of place in Macau's religious affairs and has the honour of being the place where certain rituals involving the whole of the Chinese community take place.

In the South of China the fishing community is at the lower end of the social strata and they are usually referred to pejoratively as Tan-ka (疍家) which the rest in the Cantonese regard as a distinct ethnic group and define in such a way as to devalue, eliminate or marginalize them (Brito Peixoto, op. cit.). This is precisely why religion takes on such a great deal of importance for this study. The tight relationship between the Tan-ka and Barra Temple, something which can be observed at several levels, seems to prove that they gain through ritual something which is ideologically denied them, that is their integration into the rest of society and any contribution which they could make towards it.

This article shall make a preliminary examination of the rituals, legends and art in the temples which seem to indicate that the symbolism which underlies them plays an important, albeit latent, role which has been underestimated in the socio-cultural identity of the fisherman.

I

Luís Gonzaga Gomes wrote that "in Macau there is nothing of note in terms of Chinese architecture, other than the temples" and that "of all the temples which still stand in this city, Barra Temple is undeniably the most interesting both from the artistic point of view and for the beauty of the legends connected to it" (Gonzaga Gomes, 1945: p. 13). A report written in 1840 came to the same conclusion, stating that nowhere had art been put to greater effect (The Chinese Repository, 1840: p. 402). This somewhat effusive enthusiasm is offset by Ana Maria Amaro's parsimonious description of Barra Temple in which she comments that it "is one of the two Chinese temples which are considered to be of value and are included in the tourist map of the Province" (Amaro, 1967: p. 355). The other temple which she refers to is Kun Iam Temple (Kun Iam Tong 觀音堂) where the historic 1864 SinoAmerican treaty was signed and even then she only mentions it in order to differentiate it from a study on the Kun Iam Ancient Temple (Kin Iam Ku Miu 觀音古廟) which is located in the same neighbourhood. In fact, the Kun Iam Ancient Temple was the predecessor to Kun Iam Temple but was overtaken in terms of size and fame. In spite of its "extreme simplicity and even the lack of aesthetic harmony due to partial demolition which has been inflicted in the name of urban development" (Amaro, 1967: p. 356) and its obscure character, it can still serve to throw some light on the position of Barra Temple in Macau's socio-religious ambit. In other words, by studying Kun Iam Temple in Mong Ha (望厦), I hope to arrive at an understanding of A Ma Temple (Ma Kok Miu 媽閣廟) in the Barra district.

Amaro claims that the population group which owned Kun Iam Temple would have been one of the oldest in Macau and may have been established by people from Fukien Province during the early years of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) whose move into the North of the country caused riots which in turn provoked a wave of emmigration towards the South. The provincial capital of Fukien, Mong Ha Tchun (望厦村) which literally means "the village which looks onto Ha Mun (厦門), was still, at the beginning of the century, a marshy region where rice and vegetables were cultivated by a prosperous population of farmers and craftsmen. The legend which follows was collected by Ana Maria Amaro from a scholar who was supposedly directly descended from the people who founded the first village in Macau.

Barra Temple: Engravings on a rock.

The spliced prow and the painted eyes are a characteristic detail of vessels from Fukien Province. The characters 利涉大川 literally mean "it crossed the great sea with happiness". According to the legend, this is the boat which brought the Goddess to Macau.

Barra Temple: Engravings on a rock.

The spliced prow and the painted eyes are a characteristic detail of vessels from Fukien Province. The characters 利涉大川 literally mean "it crossed the great sea with happiness". According to the legend, this is the boat which brought the Goddess to Macau.

Legend on the Founding of Kun Iam Temple

"The inhabitants of Mong Ha (望厦) lived in peace, dedicated to their labour in the fields with no profitable employment available other than what they needed for their own survival. Nevertheless, they lived quite happily until one day when two goatherds who were watching over their charges nibbling the scanty grasses on the stones at the edge of the river saw a little wooden carving of the compassionate Goddess of Mercy, Kun Iam (觀音) floating in the waters at the foot of the Golden Peaked Mountain. With great devotion, they picked it up and took it back to the village.

What a lucky omen!

The statue was placed on a throne and worshipped with incense, candles and prayers on the ground near the place where she had appeared. Three smooth stones like the surrounds of a door were placed around her to form a simple alcoveshaped sanctuary as if it were really a genuine temple. This was the origin of the first temple in Macau, dedicated to the merciful Kun Iam (觀音).

Shortly after this, in the reign of Tcheung Tac Wong (正德皇), in the year Teng Mei (丁未) there was a remarkable event which profoundly affected the lives of all the villagers in Mong Ha (望厦).

After a terrifying typhoon of the kind which often comes close on the heels of storms in Macau, three foreign boats sought shelter in the harbour at the Porto da Baía. The first was Dutch, the second, Indian and the third one was Portuguese. The first two lost no time at all in lifting their anchors and leaving but the third one, the Portuguese one, stayed on.

The Portuguese sailors seemed to be merchants. The boat was badly damaged and their goods soaked so the sailors went onto dry land and made contact with the descendents of the Kai (雞) clan who were living in Barra. They asked for permission from the chief of the clan to pitch some little tents where they could take shelter and stay until their goods had dried out. They were given a licence to stay and from then on their story is common knowledge: they were the earliest settlers of the peaceful Portuguese settlement of Macau.

As the city grew, so did the cultivable land which could be developed for profitable business.

The marshes were reclaimed at the cost of hard labour and sweat. New farmers came and shacks (liu tchai 寮仔) and funny little brick houses were built round the foot of the hill and along the cultivated land. As the village grew, the old temple of Kun Iam (觀音) was not forgotten.

They had fled from persecution by the Tartar Manchus in the reign of Man-Lek (萬曆) and, loyal to their deposed emperor, had taken refuge in Macau in the hope of gathering together in a Buddhist monastery. In ancient China, no matter what the crime was, the criminal could escape punishment by becoming a Buddhist priest and thus placing himself outside the realm of civil justice. According to tradition, it was at this time that the humble monastery of Pou Tchai Sin Un (普濟禪院) was either founded or completed next to the Chapel of Kun Iam (觀音) where the old statue washed up on the river continued to be worshipped.

Once the first pavilion of the monastery with its chapel dedicated to the "Listener of Prayers" had been extended and formalized by the priests, the charitable Kun Iam (觀音) became one of the most beautiful Chinese temples in Macau, the temple which is now known as Kun Iam Tong (觀音堂). With its graceful architecture and beautiful decorations, this chapel gradually became more important than Kun Iam Ku Miu Temple (觀音古廟) until it reached a stage when most of the inhabitants of the village no longer worshipped the early sanctuary."

(Amaro, 1967: pp. 359-361)

Before continuing, it would appear to be worth giving some explanation of the Kai (雞) clan who, because of the position which they held in Barra, took on the role of go-between for the locals and the Portuguese.

"As regards the surnames of the first Chinese inhabitants, the founders of Mong Ha (望厦) village, the names Ho (何), Sam (沈), Hoi (許), Tcheong (張), Lam (林) and Tchan (陳) seem to be most evident.

According to manuscripts held by the Ho (何) family, when these early inhabitants fled, they were preceeded by some members of other families namely the Tins (田), the Pous (布), the Lous (老) and the Kais (雞). Furthermore, the latter family was possibly the first clan to inhabit Macau. Because they were not farmers, the Kai (雞) family settled on Manduco Beach (A Van Kai 下環街) at the entrance to the Inner Harbour at the foot of Barra Hill and they worked in fishing and shipping cargo."

(Amaro, 1967: p. 359)

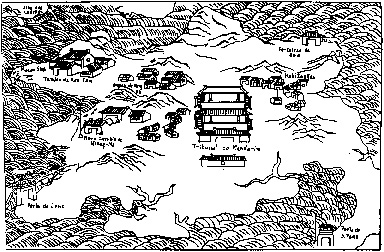

Macau - an engraving from Ou-Mun Kei-Leok ( 1751 ) written by Tcheong U-Lam and Ian Kuong-Iam (translated from the Chinese as Monografia de Macau by Luís Gonzaga Gomes).

Macau - an engraving from Ou-Mun Kei-Leok ( 1751 ) written by Tcheong U-Lam and Ian Kuong-Iam (translated from the Chinese as Monografia de Macau by Luís Gonzaga Gomes).

In order of arrival, the founding families of Macau were the Kais, the Lous, the Pous, the Tins, the Hos and the Sams, the Hois, the Tcheongs, the Lams and the Tchans. There is yet another distinction which can be made amongst those who were first to arrive: the Kais settled at the foot of Barra Hill to make their living from the sea while the rest of the clans settled in Mong Ha.

The situation can be summarized as follows:

The founding clans of Macau

Kai

Barra Village

(Fishermen

and seafarers |

Lou

Pou

Tin

Ho/Sam

Hoi

Tcheong

Lam

Tchan

Mong Ha Village

(Farmers) |

The farming clans did not constitute any problem at all and from now on no mention shall be made of them. It is the fishing and seafaring clan which requires additional explanation.

"In this respect, however, the Sam (沈) family recognizes another version which was recorded by one of their ancestors. It says that the Kai (雞) family, a surname which no longer exists in Macau, reached Macau shortly before the Sam (沈) family when they fled and they set up in an area where, many years before, the Goddess A Ma (阿媽) had made her miraculous ascent to Heaven and that this place had been marked by a stone by the pious seafarers.

In the opinion of the present day descendents of the Ho (何) family, based on the oral version which their family tells, the Kai (雞) family had already been in Macau for some years where they had been washed up by a storm and the famous legend connected to the name of Macau had been brought by them."

(Amaro, 1967: p. 359)

I have already pointed out a difference between the professional activities of the inhabitants of Barra village and Mong Ha village and we shall now see how this is repeated in terms of their religous activity with the contrast between the Goddess A Ma and the Goddess Kun Iam. It can easily be summarised in the following diagram:

Let us now turn to the origins of the name of Macau which is connected to the history of the Kai clan.

Legend of the name of Macau

(Source: Amaro, 1967)

"According to this legend, a charitable sailor took pity on a woman from Fok Kin (福建) and let her travel on his old tou sun (渡船). They met with a typhoon and through her prayers they avoided being shipwrecked unlike the other ships which were travelling with them and whose captains had refused to take the poor woman on board. When they reached the shores of Macau, which at that time was no more than a deserted peninsula or island, the young woman rose to the peak of the "Hill of Wind and Fire" (Barra Hill) and disappeared in a flash of light leaving behind no more than a shoe. The young woman was none other than Neong Ma (娘媽), the charitable Goddess A Ma (阿媽), patron of all sailors. This is the origin of the name of Macau: A Ma Au(阿媽拗) which means A Ma's Anchorage."

(Amaro, 1967: p. 350)

Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

1st Version

(Source: Teixeira, 1979)

One day, a damsel from Fukien Province wanted to board one of the junks which were heading for the South but she was refused passage on all of them for she had no money.

However, finally the owner of the poorest junk of them all took pity on the girl and offered to take her to Canton for nothing.

On the way, a terrible storm blew up and all the boats sank to the bottom of the sea with one exception. The maiden had taken the helm of this boat and steered it into a sheltered harbour. When she disembarked she climbed up onto a rock and was never seen again.

The sailors of the boat were convinced that the girl who had saved them was the goddess Neang Ma. They built a temple in honour of Neang Ma and they called it Ma-Kok-Miu (Temple on Ma's Promontory) and that is where the name of Macau comes from."

(Teixeira, 1979: p. 19)

Thus we can see that the legend of Kun Iam Temple complements the legend of Barra Temple through the legends of the name of Macau which is the link between them. In other words, the legend of Barra Temple developed from the legend of the name of Macau which, in turn, was a development of the legend of Kun Iam Temple.

I shall now make a parallel examination of the two legends and from there attempt to reach a conclusion. It should be borne in mind that there are several versions of the Barra Temple legend. We shall assume that the true legend is a combination of the various elements included in each different version (ref. Lévi-Strauss, 1958). In order to give a clearer picture of the situation, there now follow the three remaining versions.

Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

2nd Version

(Source: Gonzaga Gomes, 1945)

Before being made a god, the "Sovereign of Heaven" was simply a mortal like the rest of us. He lived in T'in Pou (田莆) in Fok-kin (福建) Province.

During the earliest days when this colony was being founded, Fok-kin's foreign trading was carried out almost exclusively through Macau. From time to time, little tugs arrived after journeys of about a fortnight, laden down with precious tea leaves which were then immediately re-exported to the West.

One day, when he was still a mortal, the "Sovereign of Heaven" took a notion to go and visit Macau.

The passengers were all ready, waiting to set off, when they saw a graceful maiden arrive in a hurry. She was wrapped in a snow-white shawl and her tiny little feet swayed precariously in the sodden ground. It seemed as if she would never reach the boat.

In their impatience to set off, the people on board shouted to her to move more quickly and, as the intriguing beauty stepped onto the plank leading up to the boat, the tiny silken shoe on her left foot came undone and fell off. At the very same moment, the boarding plank was raised and the maiden was thus obliged to spend the whole journey with her left foot unshod.

With its sails unfurled and dragged along by the force of a monsoon, the boat headed swiftly for Macau's shores.

Now, the space on deck the cramped boat was extremely limited and the boat was crammed full of passengers because, at that time, sailings between Fok-kin and Macau were not so frequent. As a result, the mysterious young woman could not find any spot where she could sit down and rest.

Once the boat reached the high seas, it started to rock. The waves towered and then crashed down, tossing the little boat from side to side and throwing the passengers on top of each other.

But what was strangest of all was that, no matter how violently the boat pitched, the mysterious traveller remained absolutely still, unaffected by the inclement weather.

At that point, nobody noticed this strange fact except a tea dealer called Sam-Man (沈文). He was both a discreet and an intelligent man who could not help wondering about this unusual state of affairs.

Let us now turn to the origins of the name of Macau which is connected to the history of the Kai clan.

Legend of the name of Macau

(Source: Amaro, 1967)

"According to this legend, a charitable sailor took pity on a woman from Fok Kin (福建) and let her travel on his old tou sun (渡船). They met with a typhoon and through her prayers they avoided being shipwrecked unlike the other ships which were travelling with them and whose captains had refused to take the poor woman on board. When they reached the shores of Macau, which at that time was no more than a deserted peninsula or island, the young woman rose to the peak of the "Hill of Wind and Fire" (Barra Hill) and disappeared in a flash of light leaving behind no more than a shoe. The young woman was none other than Neong Ma (娘媽), the charitable Goddess A Ma (阿媽), patron of all sailors. This is the origin of the name of Macau: A Ma Au(阿媽拗) which means A Ma's Anchorage."

(Amaro, 1967: p. 350)

Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

1st Version

(Source: Teixeira, 1979)

One day, a damsel from Fukien Province wanted to board one of the junks which were heading for the South but she was refused passage on all of them for she had no money.

However, finally the owner of the poorest junk of them all took pity on the girl and offered to take her to Canton for nothing.

On the way, a terrible storm blew up and all the boats sank to the bottom of the sea with one exception. The maiden had taken the helm of this boat and steered it into a sheltered harbour. When she disembarked she climbed up onto a rock and was never seen again.

The sailors of the boat were convinced that the girl who had saved them was the goddess Neang Ma. They built a temple in honour of Neang Ma and they called it Ma-Kok-Miu (Temple on Ma's Promontory) and that is where the name of Macau comes from."

(Teixeira, 1979: p. 19)

Thus we can see that the legend of Kun Iam Temple complements the legend of Barra Temple through the legends of the name of Macau which is the link between them. In other words, the legend of Barra Temple developed from the legend of the name of Macau which, in turn, was a development of the legend of Kun Iam Temple.

I shall now make a parallel examination of the two legends and from there attempt to reach a conclusion. It should be borne in mind that there are several versions of the Barra Temple legend. We shall assume that the true legend is a combination of the various elements included in each different version (ref. Lévi-Strauss, 1958). In order to give a clearer picture of the situation, there now follow the three remaining versions.

Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

2nd Version

(Source: Gonzaga Gomes, 1945)

Before being made a god, the "Sovereign of Heaven" was simply a mortal like the rest of us. He lived in T'in Pou (田莆) in Fok-kin (福建) Province.

During the earliest days when this colony was being founded, Fok-kin's foreign trading was carried out almost exclusively through Macau. From time to time, little tugs arrived after journeys of about a fortnight, laden down with precious tea leaves which were then immediately re-exported to the West.

One day, when he was still a mortal, the "Sovereign of Heaven" took a notion to go and visit Macau.

The passengers were all ready, waiting to set off, when they saw a graceful maiden arrive in a hurry. She was wrapped in a snow-white shawl and her tiny little feet swayed precariously in the sodden ground. It seemed as if she would never reach the boat.

In their impatience to set off, the people on board shouted to her to move more quickly and, as the intriguing beauty stepped onto the plank leading up to the boat, the tiny silken shoe on her left foot came undone and fell off. At the very same moment, the boarding plank was raised and the maiden was thus obliged to spend the whole journey with her left foot unshod.

With its sails unfurled and dragged along by the force of a monsoon, the boat headed swiftly for Macau's shores.

Now, the space on deck the cramped boat was extremely limited and the boat was crammed full of passengers because, at that time, sailings between Fok-kin and Macau were not so frequent. As a result, the mysterious young woman could not find any spot where she could sit down and rest.

Once the boat reached the high seas, it started to rock. The waves towered and then crashed down, tossing the little boat from side to side and throwing the passengers on top of each other.

But what was strangest of all was that, no matter how violently the boat pitched, the mysterious traveller remained absolutely still, unaffected by the inclement weather.

At that point, nobody noticed this strange fact except a tea dealer called Sam-Man (沈文). He was both a discreet and an intelligent man who could not help wondering about this unusual state of affairs.

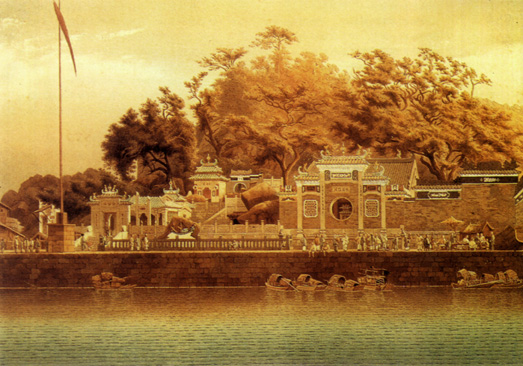

drawn by Auguste Borget (1809-1877) from <I>La Chine et les Chinois. </I>

Barra Temple with the engraved rock in the foreground from <I>Ou-Mun Kei-Leok </I>(1751) written by Tcheong U-Lam and Ian Kuong-Iam. </figcaption></figure>

<p>

From then on, Sam-Man resolved to spy on everything the mysterious traveller did and, when the boat anchored in front of Barra Temple, he did not let her out of his sight.

</p>

<p>

He watched her disembark along with the other passengers and then head for the hill where the temple is now located with a solemn piety in her step. When he least expected it, the maiden vanished from sight along with all traces of her footsteps. Sam-Man, who had also climbed up the hill, found a wooden effigy of a deity whose left foot was unshod in a spot on the slope which was still wet with the morning dew.

</p>

<p>

He then had no more doubts that his unusual travelling companion was none other than the deity who was represented in wood and whose soul was not caught up in earthly matters.

</p>

<p>

Once he had recovered from his astonishment at his sudden discovery, and because, like any other Chinese, he was a practical and concerned man, he wasted no further time in thinking but ran straight to a lottery shop selling slips for the game of )

Fortune smiled on Sam-Man and, in accordance with his promise, he ordered a small temple to be built which now stands at the back of the buildings in the temple complex. And as the deity had shown that she could give great benefits to those who worshipped her the temple was frequently visited by her followers.

As a result of the growing numbers of crowds, the followers of the "Sovereign of Heaven" pledged to build her a new temple which is now the temple which can be seen at the front of the complex. As the years went by, more extra chapels were added while nobody dared to order the original small sanctuary to be demolished. According to the faithful, this is where the body of the "Sovereign of Heaven" lies under a little effigy with its left foot unshod."

(Gonzaga Gomes, 1945: pp. 13-16)

Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

3rd Version

(Source: The Chinese Repository, 1840)

In the reign of Wanleih, of the Ming dynasty (about A. D. 1573), there was a ship, from Tseuenchow foo in the province of Fuheën, in which the goddess Matsoo po was worshiped. Meeting with misfortunes, she was rendered unmanageable and driven about in this state, by the restless winds and waves. All on board perished, with the exception of one sailor who was a devotee of the goddess, and who, embracing her sacred image, with the determination to cling to it, was rewarded by her powerful protection, and preserved from perishing. Afterwards when the tempest subsided, he landed safely at Macau, whither the ship was driven. Taking the image to the hill at Ama ko, he placed it at the base of a large rock - the best situation he could find - the only temple his means could procure.

About fifty years after this period, in the reign of Teenke, there was a famous astronomer, who from some correspondence (unknown to common mortals) between the gems of heaven and the jewels of earth, had discovered that there was a pond in the province of Canton containing many costly and brilliant pearls, upon which he addressed the emperor, respectfully advising him to send and get them. His imperial majesty, availing himself of the important information, dispatched a confidential servant in search of this wonderful pond. On arriving at Macao, and passing the night at the village of Ama ko, the goddess appeared to the messenger in a dream, and informed him, that the place he sought for, was at Hopoo in Keaou chow or the district of Keaou. He went to the place and procured several thousands of the finest pearls. Glowing with gratitude for the secret intimations he had received, he built a temple at Ama ko, and dedicated it to his informant.

(The Chinese Repository, 1840: p. 403)

The Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple

4th Version

(Source: Tcheong-U-Lam and Ian-Kuong-Iam, 1751)

There are three strange stones in Macau. One of them is called Ieong-Sun-Seak (洋船石) meaning "Rock of the Oceanic Boat". Tradition tells that during the reign of Man-Lek (1573-1620), a large trading boat from Fukien was hit by a storm and was consequently in great danger. At the same instant, a saint could be seen standing on the slope of a hill. The boat regained its balance and the members of the crew then build a temple dedicated to T'in-Fei (天妃) whose name means the "Celestial Concubine". They called this spot Neong-Ma-Kok (娘媽閣,"Neong-Ma bridge") as Neong-Ma is the name given to the Celestial Concubine in Fukien Province. They engraved a boat and four Chinese characters on the rock at the front of the temple. The four characters were lei-sip tai-ch'un (利涉大川) which mean "it crossed the great sea with happiness" and they were intended to spread the news of this saint's extraordinary powers.

The other rock is called Hoi-K'ok-Seak (海角石) meaning "Sea View Rock", located at the point of Neong-Ma. It rises from the left-hand side to a height of twenty eight metres and on it are the characters hio-k'ok (海角) which is another Chinese word for Macau. Each of the characters measures over two metres across.

The third rock is the Ha-Ma-Seak (蛤蟆石) which means "Frog Rock" and is a roundish rock coloured a light green. Whenever the wind blows and it rains, when the tide begins to come in in the afternoon, the stone makes a kok-kok sound."

(Tcheong-U-Lam and Ian-Kuong-Iam, 1751: p. 50)

A comparative reading of the two legends reveals the following pertinent contrasts:

two goatherds

|

a seafarer (lst ver.)

a tea dealer (2nd ver.)

a sailor (3rd ver.)

a merchant boat (4th ver.) |

saw a wooden statue bobbing

in the water at the foot of

Mong Ha hill

|

met a maiden who climbed onto a cliff

and was never again seen (lst ver.)

found a wooden effigy on the slope of

Barra hill (2nd ver.)

saw a saint standing on the slope of

a hill (4th ver.) |

the statuette was of the

goddess Kun Iam

|

the wooden effigy was of the goddess

A Ma (2nd ver.)

the image was of the goddess Matsoo

(3rd ver.)

she was the goddess Neang Ma (1st, 4th ver.) |

they picked up the image and

took it to the village |

the sailor took it to Barra hill (3rd

ver. |

the statue was placed on a

throne, worshipped with incense,

candles and prayers and surroun-

ded by three stones |

the sailor placed the effigy at the bottom

of a large rock (3rd ver.)

|

the three stones were smooth

and were like the surrounds to

a door |

in Barra there are three unusual stones

and one of them is shaped like a frog (4th

ver.) |

As has already been pointed out, there is a distinction between the "farmers" and the "fishermen and seafarers" which can be seen once more in the constrast between the "goatherds" and the "merchant, seafarer, sailor, etc.". In other words there is a contrast between "land people" and "sea people". At this point there seems to be a contradiction for the "land people" discover evidence of the goddess Kun Iam in the Water at the foot of Mong Ha hill while the "sea people" find evidence of the goddess A Ma (under the different names of Matsoo, Neang Ma, etc.) on land at the top of Barra hill. In the same way the "land people" take the statuette to their village, a cultivated, inhabited area while the "sea people" take their effigy to a hill, a non-cultivated, deserted area. Later, in the village, the statuette is worshipped with incense, candles and prayers, or rather the religious rite takes place according to the norms, regulations and preconceptions of a cultivated area within the sphere of culture. On the other hand, the "sea people" place their statuette next to a large rock, or rather a natural phenomenon in such a way as to make the religious rite part of the natural process. This contrast is reinforced by the fact that the "land people's" statuette is surrounded by smooth (domesticated) stones which are similar to a doorway. On other words, it is marked by "culture" while the "sea people's" reference point is notable for its strange forms which cannot be related to recognizable shapes or, when they can be, are animal-like shapes which seem to suggest a "natural" state. This point shall be examined later on but for the moment we shall summarize the contrasts in the following way:

Nevertheless, these contrasts hide one element which is evidently common to both. The sea is an essential part of both sets of legends either in the establishment of the cult or the discovery of evidence of a divine presence: in the legend of Kun Iam Temple its founding is due to a wooden statuette found in the water; in the legend of Barra Temple water was the driving force which caused A Ma to appear. In both legends there is a clearly defined movement from water to land and, in a certain way, from chaos to cultured order.

Meanwhile, it has been shown that, both in the legend of Kun Iam Temple and the legend of Barra Temple, evidence of the divine presence shown by the discovery of the statuette is a propitious sign, forecasting prosperity. This is displayed by the arrival of the Portuguese merchant ship in the first case and by the discovery of treasure in the last case. It should be remembered that the treasure is found in a lake and that it consists of pearls which seems to indicate an emphasis on the link with the water. The significance of the pearls can be better understood against a background of ethnography. Research in this area has produced a revealing comment from a fishermen who claimed that "pearls are the scales of the sturgeon" and in fact, in line with traditional Chinese thought pearls are supposed to originate in fish scales. The Chinese word for "fish", yu (魚) is a homophone of the word yu (裕) which means "wealth", "abundance". It is in this metaphorical sense of the word that Chinese tradition deems it appropriate to eat fish at the dinner to celebrate the Lunar New Year in order to guarantee continually renewed wealth, year after year. Therefore, pearls have multiple connotations which indicate that the idea of prosperity emanates from sea products. The fourth version of the legend seems to prove this point with its reference to the drawing on the rock at Barra Temple. The four characters which appear on the picture of the boat, lei-sip tai-tch'un (利涉大川) were translated by Gonzaga Gomes as "it crossed the great sea with happiness". However, it is interesting that the character lei (利), translated literally as "happiness", is linked to the idea of benefit and is also associated with ideas of "profit" and "financial rewards" and can thus be translated as "prosperity". Now the legend of Kun Iam Temple makes it absolutely clear from the start that the inhabitants of Mong Ha, that is the farmers, "the inhabitants of Mong Ha (望厦 ) lived in peace, dedicated to their labour in the fields with no profitable employment available other than what they needed for their own survival". In other words, if on the one hand the text starts off by establishing a contrast between the farming and the fishing communities, then on the other hand it leaves no room for doubt that propsperity is only possible though an exchange of goods in which the sea and the people connected with it play a crucial role.

It could then be said that the legend of Kun Iam Temple and the various legends of Barra Temple share a common thread just as Lévi-Strauss claimed that myths which undergo the same series of transformations also share a common thread. I began this article by discussing how these transformations operate through a system of contrasts. It is obvious that there is a difference between the fishing community and the farming community. From there, there is an analogy which repeats these differences in an inverted version which links the latter group to the sea and stormy waters and, in effect, the forces of nature. Finally, it symbolizes original chaos. When all of this is taken into account along with the evidence of a divine presence and the prosperity related to it, it seems to be that the origins of cultured order, revindicated by the farmers, are to be found in water and natural chaos.

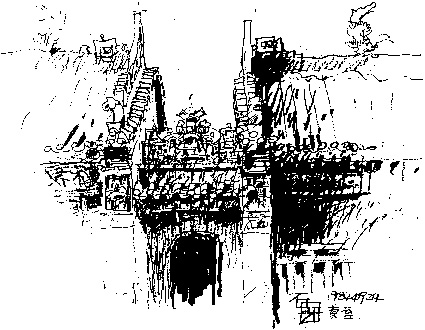

Kun Iam Temple(a detail)-drawing by Guilherme Ung Wai Meng.

As the goddesses Kun Iam and A Ma have already been mentioned, it is worth taking the time to pause and make an examination of each of them. It should be remembered that Kun Iam (觀音), the goddess of mercy who listens to the laments of the world, was, originally, a Buddhist deity, the Boddhisattva (pou sat, 菩薩 ). This deity is also known as Avalokites vara, the father of Tibetan Buddhism of whom the Dalai Lama is a reincarnation. Avalokites vara was then translated into Chinese as "he who listens (to the world)", or rather Kun Iam (觀音). In Indian and Tibetan art Avalokites vara is represented according to concepts of feminine beauty which has led him to be viewed as a goddess, something which is reflected in iconography from the beginning of the 9th century. In China Kun Iam is commonly represented as a madonna wearing a long white dress with a child on her lap. She is an extremely popular goddess, particularly in the South of China where she is associated with fertility cults (Bredon and Mitrophanow, 1927; Eberhard, 1986; Williams, 1932; Yang, 1961).

The goddess A Ma (阿媽), literally meaning "mother", is also known as Ma Chou (媽祖) and various other titles, the most important of which is "Empress of Heaven" (Tin hau, 天后 ) in the Taoist pantheon. According to a legend recorded by Bredon and Mitrophanow (1927) and Williams (1932), she was born to a family of fishermen called Lin in a little village near Foochow in Fukien Province. Her birth was announced by the appearance of a red light which came down over her parents' home. She proved, from a very early age, that she was an exceptional child, displaying great saintliness and daughterly devotion. One day, she dreamed that her father and brothers were in two junks on the sea when they met with a terrible storm. At once, she began to pull the boats towards the shore with two ropes. However, at the very same moment, her mother shook her arm to wake her up and by doing so one of the boats broke loose. Later on, the brothers said that they had seen a very beautiful girl walking on the water leading them to safety but that she had not been able to save the other boat where their father was. She died at the age of twenty eight, still a spinster. After her death, seafarers began to put round stories of how she had appeared to them and saved them from the ravages of a storm at sea. The same light which had appeared on the day she was born frequently appeared at the top of masts (the Saint Elmo's fire commonly seen by sailors) and was interpreted as a sign of protection from the goddess (Ward, 1982: p. 40). The junks began to carry a statue of her on board and temples were built along the coastline of Canton and Fukien Provinces in her honour. The traditional date given for her birth is the twenty third day of the Third Moon of the year 901.

After being worshipped by the people for two centuries, she was officially canonized and given various honorary titles. After she attended the Imperial Chinese Fleet in the reconquest of Formosa, she was promoted to the level of "Empress of Heaven" (Tin Hau, 天后 ). She is always accompanied by two helpers: "Thousand League Eyes" (千里眼) and "The Ears of the Gentle Wind" (順風耳) who are the possessors of exceptional senses which they use to protect seafarers. A Ma is located in an outstanding position in the firmament in the Ursa Major constellation, the most important constellation in Taoist belief. Ursa Major is also the "celestial mansion" of the Buddhist deity Maritchi, the "Mother of Measurements" who records the behaviour of human beings and decides on how long they shall live (Williams, 1932: p. 338). Similar to Kun Iam, Tin Hau is associated with fertility cults and is the protectress of women and children (Bredon and Mitrophanow, 1927; Eberhard, 1986; Ward, 1982; Williams, 1932; Yang, 1961).

The existence of transformations at several levels of Chinese religion has already been dealt with in the field of specialised literature (Chan, 1953; Freedman, 1974; Yang, 1961) and, in this specific case, the shared identification of Kun Iam Tin Hau in the South of China has already been recorded. My own research in this area has proved these theories despite the fact that it is only that sector of the community which has links with the sea which is aware of this fact. Hence, my experience has been that, for example, one Tan-ka, on being asked the identity of Tin Hau, promptly replied "Tin Hau is Kun Iam". For this fisherman, the statement expressed a truth which those "land dwellers" who were present immediately questioned and later advised me to ignore "what those poor ignorant fishermen say".

Therefore, it is evident that on a factual level the distinctions between these deities, whether they are Taoist or Buddhist, are not very pertinent. If the fishermen believe that "Kun Iam is Tin Hau" then it would seem that we are not dealing with two different entities but rather two different versions of the same entity. It could even be said that this is a distinction which can be reduced to how the phenomenon is described by the "sea people" and the "land people" respectively.

I began this article by commenting that the contrasts between the "sea people" and the "land people" which have been observed in Macau originated in the relationship between the fishing community and the agricultural community. There seems to be a correlation between the social and economic position of these communities in structurally identical cases where these contrasts are in evidence. The contrast between these two sectors inevitably leads to a relationship of mutual exchange (Brito Peixoto, 1987: pp. 16-20; 1988: p. 20; 1988b).

Thus it can be seen that, right from its very origins, Macau has never been a homogeneous society. Primeval social organization has a dual community of the kind already described in which religion plays an important part. Social differentiation may be the reason for the worshipping of different deities whose powers are directly linked to the interests of each particular sector of the community. Consequently, social differences are reflected in the organization of the temples, a cohesive element for each particular group. Nevertheless, the fact that the deities enshrined in each temple, or rather the temples themselves, have nothing to do with each other does not necessarily mean that they had to compete against each other. Quite in the contrary, many religious ideas in China were viewed as being mutually complementary (Yang, 1961) and, in certain circumstances they could contribute to the cohesion of the whole community. This could happen for example when a deity assumed a particular significance or when there were common interests, namely in the area of mutual exchange. The socioreligious picture in Macau satisfies these conditions. A dual community organized in this way needs to express solidarity on the one hand while, on the other hand, it also needs to reinforce its differences. Finally, it could be foreseen that this system would give way to mutually complementary forms of worship, forms of worship which allowed the religous similarities to be expressed as if they were differences.

We have seen that the fishermen identify the two deities as being one and the same but, despite this, it seems that A Ma is regarded as a symbol of wholeness, something which does not apply to Kun Iam. In fact, A Ma is not only associated with water as the protectress of seafarers, but also with land where the marks of her presence are to be found: the episode where the goddess loses her shoe defines her link with the land and constitutes a symbol of autochthony. This symbol can also be applied to the fishermen, the first clan to arrive and thus the first "inhabitants" of the region. The shoe episode is also linked to the other episode in the legend telling the origin of Macau's name where it is told that the goddess A Ma left a shoe on a rock. She is also associated with Heaven and the Celestial Fire (her birth is marked by a light), she joins Ursa Major, she is the light which appears at the top of the masts, etc.). It may be due to these reasons that she plays a fundamental role in the legend of Macau's name and is regarded with the utmost importance by the Tan-ka.

II

A Ma Temple (1850 by R. V. Decker.)

The importance which Barra Temple has for the social and religious life of Macau is especially evident during the Lunar New Year. The festivities which take place at this time of year have already been well described in the classic works by Bredon and Mitrophanow (1927) and Eberhard (1952) so I shall not spend time discussing the details. However, the profound social, moral, personal and cosmic significance of the Chinese New Year can never be underestimated particularly because the ideas and feelings which are associated with it are difficult for Westerners to appreciate.

One year is coming to a close and another one is about to begin so the dominant idea is one of renewal: on a moral level, it is a time to begin again, leaving all bad feelings and the mistakes of the past behind: socially, it is a time for meeting, for reconciliation and restoring harmony: personally, there is the hope of paying off debts, of finishing off projects and embarking upon a new series of even greater successes. According to traditional Chinese thought, all of this is associated with the beginning of Spring when Yang (陽) returns. This is a time of cosmic movement and Man and the society in which he lives participate in this movement.

On the seventh day of the New Year, everyone ought to add on a year to his or her age as this is the birthday of all mankind. The celebrations at New Year are the longest, noisiest, most colourful and happiest of the whole year and they are, without a doubt, the most important public celebrations. The festivities focus on the home and are the most important family and community event of the year. On New Year's Eve there is a dinner for all the members of the family and nobody can be absent from this, even those members who have passed away are present on a spiritual level. The empty places are marked by a bowl and chopsticks. New Year is a time when mortals are in contact with the world of benevolent spirits (san 神) through the intermediary Chou Kuan (灶君), the God of the Stove or the God of the Kitchen. On the 24th day of the Twelfth Moon, this god sets off for Heaven (Tin 天 ) where he reports to the Jade Emperor (玉皇) on what he has seen over the previous twelve months. This is a period when mortals are particularly exposed to the influences of malevolent spirits (Kwai 鬼 ) which are let loose on New Year's Eve (Kwoh Nin 過年 ) and which must be scared away with several kinds of exorcisms, the most basic of which is to set off fire-crackers (pau cheong 爆仗 ). This is also a special occasion for worshipping the Ancestral Spirits (祖先), the Celestial Spirits (天神) and the Terrestrial Spirits (地主) or, in the case of the Boat people, the Water Spirits. Finally, it is a particularly propitious time for visiting the temple and having one's fortune for the coming year told.

In Macau, New Year is announced early with the arrival of fishing junks which begin to collect in the shelter of Macau's Inner Harbour at the entrance to which Barra Temple stands. During this time of year the religious characteristics of Macau's fishing community are expressed in a dramatic form: all fishing activity comes to a complete standstill and the fleet stays in the harbour. The boats may not move from where they are anchored from the last day of the Twelfth Moon until a determined day in the New Year which is set through divination. On the chosen day (in 1988 it happened to the fourth), all of them go through an identical ritual (tche sun 車船 ) literally meaning "engine-boat" after worshipping the Ancestral, Celestial and Water Spirits. The silence is broken by the explosion of fire-crackers and the engines of the boats being put into gear. Immediately afterwards, all the boats head for the entrance to the Inner Harbour and they turn their prows towards Barra Temple which faces the sea. They then begin a new ritual (han cheong 行張 meaning "to move - to open") where they worship the goddess A Ma (pai A Ma 拜阿媽 ). After this, the ban is lifted. Some of the boats go back to their moorings where they will stay on for a few more days and other boats return to their normal activities or return to where they came from.

In fact, Barra Temple is not only the most significant reference point for Macau's floating population but also for fishermen from Hongkong and other ports in this region. Sailors come here to join up with their relatives and to enjoy a rest after a year of hard work. At the same time they fulfill the religious obligations which link them to the temple. Barra Temple has a reputation for excellent fong soi (風水). On the one hand, there is the propitious geomantic layout of the hill, rocks, water and other natural phenomena. On the other hand, there is the positive influence of the deity who resides there and distributes prosperity and success in fishing, good health and many children. All of these are benefits which in one way or another have a direct effect on the life of the fisherman (Brito Peixoto, 1988b). In turn, the fisherman is sure to return to the temple at New Year and the other cyclical festivals as it is considered to be obligatory for all to offer their thanks to A Ma.

The charismatic attraction of Barra Temple pervades the whole of the closed fishing community. On New Year's Eve, it is especially evident: crowds of people fill the streets of Macau with no other aim than to "go for a walk in order to change their luck" (hang van 行運 ). Closer inspection reveals that there are certain spots where people are to be found in greater concentration. Crowds converge on Barra Temple and a queue of thousands of people stretches back for hundred of metres from the crammed entrance. Worshipping continues until the early hours of the morning and is carried on during the days to follow. The temple is submerged in a cloud of incense and hemmed in on one side by the fishing junks round the foot of the hill. Nevertheless, the fishing community, which stands out in an urban context, constitutes no more than a tiny minority in the crowds of faithful who flock to the temple. This is not only a "fishermen's" temple. Rather, the visitors are from extremely diverse groups and social strata. In other words, the scene at Barra Temple is representative of all the Chinese community.

It should be remembered that Chinese temples are built and maintained solely through voluntary donations. Each temple functions autonomously and there is no central organization to control and coordinate what they do. The various deities (and the temples which are dedicated to them) have different functions and specific places are regarded as being more or less efficacious by those who visit them to offer up their prayers.

The fate of any temple is affected by various factors which can either lead it to the heights of popularity or send it into the depths of neglect. Over the last five centuries, Barra Temple has been able to maintain a vigour which has guaranteed it prime place in Macau's social and religious life. Part of the reason for its great attraction within the population as a whole lies in the tight relationship between the temple and the Tan-ka, the floating population.

An examination of the traditional myths, rites and art connected with this temple reveals the sociological contrasts between the fishermen and the land community and contributes to an understanding of the Tan-ka's social identity.

Ⅲ

In Macau, the Chinese fishermen are at the lower end of the social strata and they are usually referred to pejoratively as Tan-ka, a group which the rest of the Cantonese regard as a distinct ethnic minority and define in such a way as to devalue, ignore or marginalize them. The specific details of the Tan-ka's social morphology can be accurately explained by the theories concerning their ethnic origin which present them as tribal, autochthonous populations which do not belong to the Han group. The Chinese who attempt to link their racial origins to the Tan group (an aboriginal group in the South of China) and western researchers who insist on their cultural isolation are not free from these prejudices. Precisely how weak these viewpoints are is clearly reflected in the fact that they are unable to explain how the group has assimilated certain aspects of Han culture, especially when it is obvious that the two cultures have coexisted in the South of China over thousands of years.

If we turn the traditional approach on its head, then we can see that the argument throughout this series of articles can be divided into the following areas:

•there is a sociological contrast between the Tan-ka and the land community;

•the sea dwellers and the land dwellers have maintained a tight relationship throughout time in economic and religious terms;

•the sea dwellers' identity is not the result of their "isolation" but rather their "links" with the land dwellers.

I have attempted to give a sociological explanation of the Tan-ka by examining their position amongst the rest of the local community. The first article, "Sea People, Land People" discussed the characteristic contrasts between the two communities within the wider field of the ethnography of the entire region. The second article, "Habitat, Technology and Society", established an empirical base founded on an analysis of the ecological and technological conditions. It examined fairly technical aspects but always in terms of the hypothesis that the fishing community should be seen in terms of its differences from the traditional models of social organization in the South of China. The third article in the series, "Tan-ka, U-Lan", concentrated on one particular feature of the contrast between the sea people and the land people, the symbiotic relationship between the fisherman and the wholesaler/financier. This takes the form of a complex system of exchanges which is constant and perpetual, and defines the differences between the two communities through each side of the relationship. This article has attempted to place the antinomy between the Tan-ka and the land community on a social and religious level. By analysing the legends concerning the founding of A Ma Temple (associated with the sea people) and Kun Iam Temple (associated with the land people), it is obvious that they have the same mythical structure, a fact which demonstrates that there are ideological features in the sociological contrast which has already been examined. The art, legends and rites which have been analysed reflect a close link between the Tan-ka and the mythical origins of Macau, the goddess A Ma and Barra Temple. All of this indicates that the Tan-ka are an important part of the community as a whole despite the fact that they are at the lower end of the social strata with clearly defined limitations resulting from endogamy and their associations with nature and the sea.

In spite of the limited ground which these articles have covered and their very specific objectives, I hope that they have contributed to a better understanding of the factors which make up the Tan-ka's social identity.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amaro, Ana Maria

1967 "O Velho Templo de Kun Iâm em Macau". Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, vol I, pp 355-436.

Batalha, Graciete Nogueira

1987 "This Name of Macau", Review of Culture No 1, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 7-14.

Bredon, Juliet & Igor Mitrophanow

1927 "The Moon Year". Shanghai: Kelly and Walsh. Rept. Oxford Univ. Press 1982.

Brito Peixoto, Rui

1987 "Boat People, Land People", Review of Culture No 2, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp.19-20.

1988a "Habitat, Technology and Society", Review of Culture No3, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 8-20.

1988b Tan-Ká, U-Lan, Financial and Economic Relationships in the Fishing Community of Southern China, Review of Culture No 4, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 7-14.

Chan, Wing-tsit

1953 Religious Trends in Modern China. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chinese Repository (The)

1840 Description of the Temple of Matsoo po at Ama ko in Macao. The Chinese Repository, Canton, Vol IX, p 403.

Dicionário de Português-Chinês

1962 Pub. by the Provincial Government, Macau, Imprensa Nacional.

Eberhard, Wolfram

1986 A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols. Translated from the German by G. L. Campbell. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Freedman, Maurice

1974 "On the Sociological Study of Chinese Religion". In: Arthur P. Wolf, ed., Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Standford University Press, pp 19-41.

Gonzaga Gomes, Luíz

1945 "A Lenda do Templo da Barra". In: "Curiosidades de Macau Antiga". Offprint from Renascimento, pp. 13-16.

Huang, Parker Po-fei

1970 Cantonese Dictionary. Yale University Press.

Levi-Strauss, Claude

1958 Anthropologie Structurale. Paris: Plon.

Smith, Arthur H.

1899 Village Life in China. New York: Fleming H. Revell.

So, C. L.

1964 "The Fishing Industry of Cheng Chau". In: S. G. Davies, ed., A Symposium on Land Use Problems in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press.

Techeng-U-Lâm and Ian-Kuong-Iâm

1971 OU-MUN KEI-LEOK Monografia de Macau. Translated from Chinese by Luíz Gonzaga Gomes, 1950, ed. Quinzena de Macau, October, 1974 - Lisboa. Macau: Tipografia Mandarim.

Teixeira, Pe. Manuel

1979 Templo Chinês da Barra Ma-Kok Miu. Macau: ed.

Topley, Marjorie

1964 "Capital, Saving, and Credit among Indigenous Rice Farmers and Immigrant Vegetable Farmers in Hong Kong". In: R. S. Firth and B. S. Yamey, eds., Capital, Saving, and Credit in Peasant Societies. Chicago: Aldine, pp. 157-186.

Ward, Barbara

1955 "A Hong Kong Fishing Village". Journal of Oriental Studies, no 1, pp 195-214.

1982 Chinese Festivals. Hong Kong: South China Morning Post.

Williams, C. A. S.

1932 Outlines of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives. Originally published by Kelly and Walsh, Shanghai. New York: Dover, 1976.

Yang. C.K.

1961 Religion in Chinese Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

NOTES

(1) According to the Department for the Preservation of Heritage in the Cultural Institute, there are around eighty temples in Macau. This figure excludes the altars and niches which are often found at the opening of streets or the entrance to different quarters of the city. The city covers a surface area of 5.4km2 some of which is land which has been reclaimed from the sea.

(2) The assassination of Governor Ferreira do Amaral in 1849 was linked to claims that he was responsible for violating graves when the ancient village of Mong Ha was being modernized. (Amaro, 1967: p.362)

* Diploma in Clinical Psychology (ISPA), Graduate in Ethnological and Anthropological Sciences (ASCSP). Masters in Social Anthropology (King's College Cambridge). ICM Scholarship holder.

The present article was produced in accordance with conditions stipulated by the ICM and represents the initial stage of a research project on Social and Cultural Anthropology in Macau's fishing community. The brief time in which it was written constituted no more than a pause for reflection during the work at present being undertaken. At the moment I have limited myself to giving an outline of the issues, providing provisional observations. To this end I have written for an informed public although not necessarily specialized in Anthropology or familiar with this particular ethnological field.

start p. 7

end p.