"(...) What is now Macao was, in the beginning, a small, almost totally arid peninsula, scarcely covered with grass, surrounded by inhospitable islands and only linked to Heong San Island by a neck of land.

"There were a few houses and in the Mong Há valley there lived some families, of which two had come from Fok Kin, one of them named Tsum (Sam) and the other Ho.

"There were also two pagodas, each of them claiming to have the greatest antiquity: the Barra pagoda or Ma-Kok-Miu - Goddess A Ma Temple -and the Tin Hau Seng Mou Miu, the Queen of Heaven Temple (...) (Father Manuel Teixeira, 1940)."1

According to Chinese sources, this village of Mong Há, one of the first settlements in Macao, seems to date to the 13th century. However, the history of its foundation is only based on oral tradition, on the rare chok pou of old local families2 and on the somewhat vague descriptions of rare Chinese works.

The chok pou of the Sam family reports the following about the foundation of the first village of farmers in the province of Macao:

The province of Fujian, northeast of Guangdong, covering the districts of Chaozhou and Zhangzhou, was invaded, in the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty, by the army of the new emperor, who laid waste to everything as he passed through. According to the Song dynasty, he was descended from a clan from the southern provinces and was the father of the emperor's favourite concubine.

However, the brave army of the founder of the new dynasty, commanded by General Man Heong3 of Chiau Chau, finally succeeded in defeating the last nuclei of resistance.

The subjects that remained loyal to the old emperor, and all the members of his family, were to be beheaded by order of the new monarch. 4

Interior of Lin Fong Temple in the 60's. Photograph belonging to the author.

Interior of Lin Fong Temple in the 60's. Photograph belonging to the author.

To escape from the invading force, the panic-stricken families of peaceful farmers of the villages of Meio Dia, particularly the home villages of the persecuted generals, decided to emigrate southwards seeking shelter among the numerous deserted islands of the Canton River delta.

Using fragile boats, they went down the river and looked for a place with good fong soi.5

Suddenly, in the protected meadows of the peninsula of Macao, one of the groups of emigrants sighted the Swallow's Nest.

At the same time, the auspicious land shape - a lotus leaf whose stem was represented by the isthmus linking it to Heong San island6 - and the arrangement of the local hills - in the shape of a lotus flower with a golden top7 - augured a new period of wealth and prosperity for the emigrants from Fujian.

Once the place to build the village had been chosen, on the slope of the protected south-facing hill8 and close to the partially flooded meadows, which were good for growing rice, the newcomers erected their first bamboo shacks, with roofs made of straw and lath reinforced by wooden boards.

It was necessary to choose a name for the new village and homesickness determined it. Mong Ha Chun - The Village that Contemplates Ha Mun - a permanent remembrance of their abandoned province.

Yet, it is important to note that the name of the village of Mong Ha is open to several interpretations:

The first is the literal translation of the expression:

Mong - to look from afar, to contemplate, to hope; and Ha - summer, which thus could mean Hopeful Summer or Contemplating Summer.

Considering that, in some Chinese documents of the 17th and 18th centuries "Ha" appears in the form meaning "a huge building," and is also the first letter of the word "Ha Mun" (Amoy), the capital of the Province of Fukien, the expression "Mong Há" may be thus translated as Hopeful Building, Contemplating the Building or, what seems more logical, Contemplating (from afar, and therefore hoping to return to) Ha Mun.

According to the reports of Sam's ancestors in their chok pou, the expression "Contemplating Ha Mun" is still the closest to the original idea of the village founders. However, in some writings of the last century, and even in some Chinese documents9, the expression Wong Ha indiscriminately appears instead of Mong Ha. "Wong" means florescent, brilliant, prosperous and glorious, so the expression Wong Ha may be translated, in this case, as Prosperous or Florescent Summer, or Prosperous or Florescent Village (if we understand "Ha" not as "Summer" but as the place). The village of Mong would thus correspond, so to speak, to a second Ha Mun.

This exchange of the Mong ideogram for Wong is not uncommon in Chinese, since, provided the sounds are alike, the Chinese tend to replace certain terms with others whenever these are more auspicious. This was the case with Wong Ha.

For example, in Kowloon (Hong Kong), the commercial zone of Mong Kok is also indiscriminately designated as Wong Kok, especially in written references.

It is also noteworthy that the church (probably the first or, at least, one of the first) built in the Campo by the Portuguese was called the Ermida Nossa Senhora da Esperança (Our Lady of Hope Chapel). It seems that Macao welcomed the people coming from the West and East under the sign of hope. A mere coincidence?

When the first horticulturists arrived in Macao, the peninsula did not have its present geomorphologic shape. It was a rather smaller area, whose hills were linked by small areas of mostly swampy lowland, which was invaded by an inlet. This, coming from Patane and forming what later became the San canal, extended up to the surroundings of Mong Há village.

This artificial brook was known as Tam Chong Mei10 and formed the southern natural boundary of the primitive settlement. Apart from this inlet, the village was bounded, to the east, by the In Vo hill -(the future Guia Hill), presently known in Chinese as Tong Mong Ieong11; Sa Kong, or "Sandbox", to the west, and the Kam Kok San hills (Golden Chrysanthemum Hills) and Lin Fong (Lotus Peak) to the north12.

Being farmers, the founders of the settlement started to cultivate the meadows, deriving from them their own sustenance and products that they could exchange with the fishermen living in a small nucleus at the other end of the peninsula, which was already in existence at the time of their arrival.

According to the chok pou of the Sam family, Mong Há's first inhabitants belonged to the Ho and Sam clans, followed by the Hoi, the Cheong, the Lam and the Chan.

Busy tilling the ground, which provided no more than basic subsistence, the Mong Há inhabitants lived peaceful and therefore happy lives. One day, two little shepherds who were watching over some she-goats feeding on the scarce pasture by the river, saw floating on the waters that (at that time) reached the Golden Peak foothills, a little wooden statue of the kind-hearted Kun Iam, the Goddess of Mercy. With great devotion, they picked it up and took it to the settlement. 13

A fortunate portent?

On terra firma, near the place where it had been found, the small statue was enthroned and worshipped with aromatic substances and prayers. A small and simple rocky sanctuary, in the form of a niche, was erected around it with three small cut stones, looking like the door-posts of a real temple.

This was the first temple built in Macao, devoted to the Merciful Bodhisattva Kun Iam, who listens to every prayer14.

At this time, the rural village of Mong Há comprised a few shacks located high up on the south slope of the mountainous arch of the Golden Peaks: many of these shacks were still standing until the 19th century.

The economic activity in Mong Há was then very similar to that of contemporary Chinese rural villages, based on the growing of rice and of cangcong 15 in the low and waterlogged rice paddies through a system of simple co-operation.

Of course, in the beginning, products were not traded, and the community was completely self-supporting.

The production unit comprised the group of newly-arrived families, working communally16.This first stage would have covered an initial period whose duration it is not possible to determine, but which would have corresponded to the preparation of the ground and the adaptation of the group to the new land.

The Chinese traditional concept of small family farming aims for the individual creation of wealth, based on Confucian ethics. As soon as possible, following the improvement of the local soil conditions, it gave rise to a production surplus and to bartering with the fishing population of A Ma Ou and, through them, with other nuclei in more or less distant islands. These exchanges may soon have been transformed into sales, inevitably leading to changes in the labour regime, most particularly in the pre-capitalist stage prior to the foundation of the Portuguese city in the southwestern zone of the Peninsula of Macao.

In the territory, which was still without the groves of trees which would later cover it17, the farmers who had founded Mong Há relied almost exclusively on the land, both as a means of production and for rearing livestock, and also on their own labour.

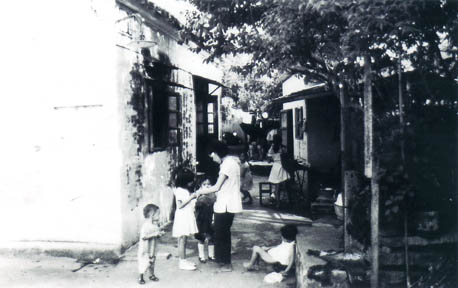

Inhabitant of Mong Há heading for the Temple of Kun Iam (1960).

Inhabitant of Mong Há heading for the Temple of Kun Iam (1960).

Prior to the arrival of the Portuguese and the foundation of the Christian city, the socio-economic structure of rural Macao was based on land exploitation as both object and means of labor. Traditional techniques of rice growing were used and production instruments were in some cases owned individually and in others collectively.

This structure was based on the family production unit, according to which the means of production were owned by the eldest: the head of the family or of the clan, the eldest man (grandfather or great-grandfather) of the traditional Chinese extended family, who shared the great common house. The political and legal powers were held by the eldest and most respected men of the village, assisted by a kind of inhabitants' board, also chosen by residents, according to the practice of the most noble virtues of Confucian morals.

In the meanwhile, the Chinese Empire consolidated its effective possession of the territory, carrying out the unification of the southern provinces. With this occupation and the political division of the Empire's territories, magistrates were appointed to run the different districts. The rank18 of these magistrates was consistent with the importance of the region they would control.

In the villages, however, the venerable old men continued to hold the political power, only submitting the most serious litigation to the court of the corresponding magistrate, known in Macao as the mandarin. Chinese sources19 report that, early in the 16th century, there was in Heong San (an island of the Macao district) an official magistrate to whom the region's inhabitants were subject and paid a lease.

At this time there was already a Chinese authority benefiting from taxes paid by the rural village of Mong Há20.As previously established, the leader of the village may have been chosen by that provincial authority, at the suggestion of its inhabitants, with the village continuing to stand as a de facto village if not a de jure one. The leader of the village was responsible for accounting, tax collection, public development such as roads or paths, and managing community granaries, since the rice paddies, in contrast to plots, continued to be subject to common cultivation. This leader was supposed to have reading skills and, either alone or helped by fair men, fellow-countrymen with understanding of the old traditions, he was supposed to be able to solve any dispute among the inhabitants of his village, to whom he should listen and give advice. As already mentioned, only in unavoidable circumstances were those litigation cases to be submitted to official justice, represented by the magistrate.

Because the farming of produce was done by individual family groups, except for the work in the rice paddies, soon a distinction developed between small-and medium-scale farmers. The size and ornamentation of their brick houses reflected the treasures each one could amass. In Mong Há, we can still find some vestiges of these houses, though, unfortunately, only a few.

The small trade that developed in the village may have been another immediate consequence, such as that associated with simple crafts, like those we can find even today in the city's mainly Chinese districts. Other items of trade that occurred mainly by river were fruit, and crushed oysters ("chunambo") extracted from the seashore rocks.

The increasing economic development of the village of Mong Há may be evidenced by both the construction of the primitive temples of Macao, which were erected in honour of the most venerated protecting divinities, and were signs of traditional Chinese piety and devotion, and the improvements and extensions they were subject to, which were always registered in the memorial stones we can see encrusted in their walls.

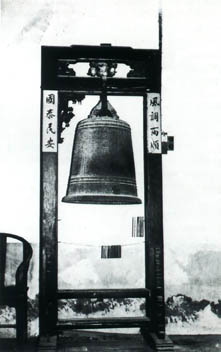

According to oral tradition, near the Isthmus, at the foot of Lotus Hill, small boats, especially "sampans", anchored near a huge rocky outcrop. Here, aromatic substances and candles were lighted, probably in veneration of Tou Tei, The Soil Spirit21 and Tin Fei, the protector of sailors, 22 to whom, according to the date engraved in a memorial stone of the existing temple, a first sanctuary was erected in around 1592, which became the third Buddhist temple to be built in Macao23.Tin Fei Miu was its first name24,which was lost, however, from the 19th century onwards when, following a fire, the temple was rebuilt and called Lin Fong Miu - the Lotus Peak Temple.

In the meanwhile, the Yuan dynasty, headed by the Mongols, had come to an end, and the triumphant Ming, of the Chinese Han people, were imposing their laws again in the various provinces of the Great Central Kingdom. Once again Macao became the shelter for many refugees.

A bonze named Seak Cheng Tai Si, a magistrate who took refuge in religion to escape from his enemies' persecutions, gaining protection from his vows, went to Macao and, together with a small group of companions, started a simple Buddhist monastery near Kun Iam chapel, in the village of Mong Há25.

According to the Sam Family chok pou, it was at this time, in the reign of Chen Tak Wong, in the year of Teng Mei 26, that the famous Western Barbarians reached the delta of the Canton River.

Following one of those typhoons that frequently ravage Macao, three foreign boats, a Dutch, a Moorish and a Portuguese, successively sought shelter in the Gate of the Bay.27

Soon the first two weighed anchor, while the Portuguese stayed. Those Portuguese appear to have been traders.

After the typhoon was over, the barbarians, their boat destroyed and their goods soaked, went ashore and came into contact with descendants of the Kai, who had settled in the Barra area, on the land of the future Manduco Beach. They asked permission from the head of the clan to build some small huts where they could take shelter and wait until their goods dried. This permission was provisionally given28.

In the beginning, the Portuguese conducted trade in Liam Po, from where they were later expelled and their trading-post torched29.

However, in the first years of the Ka Cheng reign (1522-1567), it seems that, given the huge profits made from the Portuguese trade, the Chinese authorities, both civil and military, demanded the re-establishment of their business transactions.

We quote the Chinese work Heong San Un Chi (Book VI, pp.3 and 4): "early in the Ming dynasty, during the reign of Long Cheng (1567- 1572), the Portuguese had already reached Heong San. In the province of Canton, there was a famous tradesman, a western barbarian, known by the name of Ao Pa Tou30."

There was a magistrate living near Macao, called Lam Fu, who was responsible for the governing and administering justice in the small local villages. Thanks to him, the Portuguese were allowed to build their houses, though in return for the payment of a rent amounting to 500 silver ingots a year.

On this magistrate's instructions, his superior Wong Hang, in the 14th year of Ka Cheng (1536), requested approval of a plan to transfer the Long Pak Ou31 anchorage to Ou Keang, in return for the payment of an annual fee of 200,000 kam (silver ounces)32.

Bell of one of the temples of Mong Há.

Bell of one of the temples of Mong Há.

In the 32nd year of Ka Cheng (1554), that permission not yet having been given, the commanders of the Portuguese boats made a verbal petition for some land at Hou Keang to be loaned to them, to allow them to dry some cargo that had been soaked. The Haidao, or Deputy Prefect of Coastal Defence, Wong Pak, gave his approval, and so a Portuguese settlement of straw and bamboo began to be built on the riverside of the Patane lowlands.

As the História da Dinastia Ming (History of the Ming Dynasty) reports, the annual revenue from the Hou Keang (Macao) rights amounted to 20,000 taels, in addition to the 500 taels lease, whose origin was, however, unknown33.No matter the system by which the land was granted, the Christian City in the Name of God in China34 was then founded - the first western commercial emporium in the land of the Celestial Empire.

Mong Há's inhabitants followed the arrival and the settlement of the Portuguese in the southern zone of the Peninsula first with curiosity, and then with fear, which influenced the district authorities themselves. As a consequence, in the 2nd year of Wan Li (1575), soon after the Portuguese had settled in Macao, the Chinese had a barricade built on the isthmus, known at the time by the name of Lotus Flower Stalk. This acted as a defence against the foreigners who had settled there, occupying one of the most important gateways to Canton35.

This region, in the vicinity of Mong Há, began to receive newcomers, thus causing an increase in trade and agricultural yield. This, along with the growth of the Christian city, undoubtedly fostered its development, attracting new farmers from different sites in the Province of Canton, who joined the inhabitants of Fukien to till the not always bountiful land.

In the middle of the 17th century, it is said that there were already about 7,000 Chinese36 living in the settlements of Macao (Ljungstedt, 1836).

This probably explains why, in the 35th year of Man Lek (1608), the magistrate of the province, Pun O Long, together with the representatives of other villages in the surrounding area, did not succeed in their attempt to have all foreigners driven out of Macao. Trade was blossoming and a significant number of Chinese were directly involved in it.

The 17th century rolled on, as a variety of events happened in the village. Some became legends, a mist of distortions, which is unavoidable when dealing with hearsay passed down through the centuries.

In the Christian city, the Portuguese, with the help of slaves from Goa, Malacca, Timor and Africa, among whom the Kaffirs prevailed, 37 also tilled the ground inside the city walls in small individual plots. The plot of the Jesuit College, known as S. Paulo do Monte38, became famous for its size, richness and variety of vegetables. The Christian plots improved and extended, with vegetable species brought from Goa and most likely also from Portugal. Probably they needed the paid labour both of the "Japanese" who had taken shelter in Macao and the Chinese39 who were seeking work in the city. These had settled themselves in the new lowlands around the Bazaar, in the old anchorage of the Inner Harbour where, later on, they opened shops so that they could trade with the Portuguese40.

Some seeds and slips of new vegetable species would have been taken, probably, to the village outside the walls.

With the introduction of new species and the development of the Christian city, which offered an increasingly better market, the plots of Mong Ha would have necessarily spread, extending to the Campo41

The new market created by the city, the need for services to be rendered in Portuguese houses, as well as the involvement of Chinese residents in trade, caused, as would be expected, an extraordinary change in the social and economic structure of the villages outside the walls. In the meanwhile, these expanded southwards, along the Guia Hill (old Chaul Hill)42 towards Tap Seac and the wall of the city43.

Rice growing was abandoned because it was a difficult and low-yield activity, since the water of the marshes was too brackish, the quality of the rice (red grain variety) was poor and the yield insufficient to supply not only the growing villages but also the city.

The swamps began to be filled with rubbish, and mixed intensive farming, requiring the use of manure containing large percentages of nitrogen to enrich the poor soils, became the main activity of both the members of the old families and many outlanders who, more and more, were attracted into the city.

Meanwhile, independent farm labour was decreasing since the peasants' descendants were now getting paid jobs as wet-nurses, artisans, servants, shop assistants, and interpreters, or working in other municipal services.

The labour power that had been absorbed in tilling the land was thus sold to the city's inhabitants in return for extremely low salaries44. Simultaneously, the shortage of labour on the farms forced villages to employ people on a salary basis. It was then that labourers and farm workers appeared.

The city was not always very generous with the great number of outlanders whose only resort was to seek employment in the fields of the Campo. Many of them occupied free lands, paying the corresponding lease to the mandarin of the Casa Branca45, exploiting new vacant land to build their meager little shacks.

The cultivation of these free lands, most of them used to bury the dead, became a difficult task particularly owing to the water shortage and the poor quality of the unprepared soil. Soon these sites became unattractive to farmers of the neighbouring Chinese regions who came to Macao to trade their products. These newcomers came mainly by sea and by following the tracks that linked the two main gateways of the city to its peripheral villages, crossing the Portas do Cerco through the Isthmus. 46 This resulted in many Chinese seeking other destinations.

After the 16th century, only in about 1720 did Macao begin to experience a reasonable amount of prosperity, caused by the development of the port traffic, a further consequence of certain privileges granted by the Chinese authorities. Yet, this prosperity, which was hard-won due to the high degree of dependence it necessitated, did not last. 47

A recent Portuguese building, constructed after the expropriations, and some old village houses on the hillside.

A recent Portuguese building, constructed after the expropriations, and some old village houses on the hillside.

In 1724, as a result of increasing pressure from the mandarins, the Chinese stipulated that the population of Macao could not grow, and no foreigners would be allowed to settle there48.

The city of Macao rapidly fell into decline49.The population sharply decreased and, consequently, horticultural development of the cultivated spaces outside the walls could not be significant throughout the 18th century. Early in the 19th century, the Chinese population in Macao reached 8,000 people, only exceeding by 1,000 the number estimated at the end of the 17th century50.

In the 18th century, the Mandarin House and the Lin Fung Temple, where the Chinese magistrates used to stay when they visited the territory, were the most important Chinese buildings in Mong Há. The temple boasted the most elegant stone work, thickly wooded gardens and water tanks with lotus flowers descending to the river, where a small mooring gave access to it. This was where the Mandarins stayed on their visits to Macao for political purposes or mere recreation51. Every day, the villages used to send to the city fresh products and workers through the gates that were opened to them, and each night, most of them returned to the Campo.

It seems that a certain economic and demographic balance was established in the village, which continued up to the end of the 18th century.

In the meanwhile, the Kun Ian temple was built next to the Buddhist Temple of the Pou Chai Sin Un Charitable Association, on Caranguejo Hill. According to tradition, it was here that the Merciful Kun Iam once took refuge in Macao.

This temple is one of the most important present-day attractions of the territory.

In 1825, the English began to build a road crossing the Campo to allow access to the horseracing circuit which they intended to set up in Macao52. The Mandarin of Mong Há opposed the plan in 1826. From that time on, mandarin pressure increased53.

At that time, as a side effect of the impoverishment which the city had already begun to experience a century before, tensions continued to make themselves felt in Macao, along with a deterioration in standards of behaviour and a proliferation of hatred, intrigue and robberies. (...)54.

In the Chinese villages there were echoes of this instability. The population reported that the very employees of the City Council frequently invaded the village of Mong Há, stole poultry or fruit, and abused the women. This also happened with other Europeans and descendants of the Portuguese passing through the village towards the hinterland where they went to hunt. Disputes became frequent.

In 1838, Governor Gregório Pegado, assisted by the Ouvidor (Special Magistrate) went so far as to plan the elimination of the vagrant Chinese and other people who disturbed the city (...)55 to destroy the houses rebuilt by the Chinese in Patane, to evacuate the Village of Moha to return everything to the way it was before, an attitude that was not approved by the Leal Senado (City Council), which feared eventual reactions. In a letter of the 29th December 1838, the Senado complained to the Queen about this risky project, which led the Conselho Ultramarino (Overseas Board) to issue a Proviso on the 29th of May 1839, according to which Her Majesty the Queen (D. Maria Ⅱ) ordains that the Procurator will not be allowed to grant safe-conducts or to do anything else without prior notice to the Senado.

This proviso greatly weakened the authority of the Governor of Macao and fostered the chaos experienced at the time in the territory.

Three years after the foundation of Hong Kong, after the Opium War came to an end, Macao was made a free port56.One of the saddest pages of its commercial history had just begun.

With slavery having been abolished, the English government encouraged the famous emigration of the coolies. This policy was used by many people to force these victims of the trickery and greed of numerous unscrupulous adventurers to pass through Macao. At this time, both Macao and its surroundings swarmed with malefactors, vagrants and opportunists. At sea, pirates were proliferating. In the city, egotism and greed were taking root57. Most of the Portuguese sank into corruption, vice and immorality. The attentive and apprehensive Chinese criticised and brought pressure to bear on our authorities. This was the morally decadent environment Ferreira do Amaral found when, in 1846, he took over the territory.

Governor Ferreira do Amaral was particularly interested in consolidating Portugal's position and rights in Macao, improving the moral climate and responding to the needs of a developing city. To achieve these goals, he ordered the urban development of the Campo, which was mostly vacant land covered with fields and graves; he planned to extend the city along the whole peninsular area up to the Barreira do Istmo.

First of all, it was necessary to open up roads. Thus, considering the extreme respect Chinese have for the dead and, to avoid the profanation of the graves, he ordered their removal, publishing edicts to this effect.

By carefully reading those documents, dated the 1st of April 1848, the 5th of May of the same year and the 3rd of January 1849, we can easily deduce that Governor Ferreira do Amaral was not acquainted with either the Chinese mentality or the historic version of the foundation of the village of Mong Há.

As expected, the Chinese authorities were as displeased with such plans, as were the market gardeners of the Campo. This generated a conflict which would culminate with the murder of the Portuguese governor. To make things worse, the harvest that year had been very bad and the raids by the Portuguese had increased. They had seized several consumer goods in the villages of Mong Ha and Long Tin (mainly poultry), when they went to hunt outside walls, and abused Chinese women, who were the object of sexual harassment. Adding to all this, fires, serious typhoons and epidemics were also frequent.

Works to open new streets in Mong Ha.

Works to open new streets in Mong Ha.

It seems that, from that time on, luck was not on the side of the inhabitants of the villages of Long Tin and Mong Há. Even today, many Chinese believe that all the disasters and the sudden decline of their settlements was caused by the wandering souls of their dead who had been driven out and were calling for vengeance.

In this period, Mong Há already had several streets, alleys and squares, the most important being: North Street, Bull Street and the famous Pagoda Square, facing the Kun Iam Ku Mun, near the Largo do Arvoredo, full of leafy false pagoda trees.

Around 1849, when the Portuguese began to knock down the walls of the city and to occupy the Campo, the wealthy inhabitants of the village of Mong Ha (the most prosperous nucleus outside walls) sent a letter to the mandarin governing Canton. They asked him to send someone to Macao whose mission would be to define exactly the boundaries of the area rented to the Portuguese, who, upon reaching the village in the course of their urbanisation project, demanded the payment of taxes and leases58.

In that same year of 1849, after the Governor of Macao refused an audience with the Chinese emissary, the lease collector, the tension increased, culminating with the banishment of the Mandarin from the village of Mong Há to Casa Branca, near the Barrier Gate59.The time had come for the village of Mong Há to directly intervene in the history of Macao, through one of the village founders who belonged to the Sam family.

Governor Ferreira do Amaral was murdered near the Portas do Cerco, on the occasion of one of his usual outings, accompanied by his aide-de-camp.

The oral tradition of the Chinese of Macao reports that it was a market gardener from Mong Ha, a member of the Sam family which had founded the village, who cut off the Governor's head and hand and took them to China60. According to some, this was a reaction that reflected the real anger of the inhabitants of Mong Há when they saw their meadows overrun by streets and the graves of their ancestors profaned by urban development, and after experiencing all the calamities that had befallen their settlement. Among these was a terrible fire that destroyed many dwellings, and that had started in a dense bamboo grove, the blame for which was also laid on the governor of Macao. But the true reason for the anger of the inhabitants of Mong Há, who had certainly been turned against Ferreira do Amaral both by the Leal Senado, and by the Mandarin himself, is reported in the official letter No. 233 of the 22nd of April 1848, signed by the governor himself and addressed to the Minister and Secretary of State of the Navy and Overseas Affairs61.

In this letter, the Governor reports the measures taken with regard to the Chinese owning lands in the Campo beyond the Barrier Gate, so as to urge them to legalise their ownership by means of bonds issued by the Portuguese government. An edict was published at the time, proclaiming these measures.

With this edict, Ferreira do Amaral succeeded in making the Mandarin of the Casa Branca lose face, the greatest insult a Chinese could ever suffer. A violent reaction on the part of the offended party to save his face was inevitable. However, the Portuguese governor resorted to a somewhat unfair but still successful stratagem, which partially softened his arrogance towards the Chinese magistrate.

When numbering the houses in Mong Há, the property of a subordinate of the Mandarin was not included. This allowed the Portuguese to gain the concession of the re-opening of the Barrier Gate, which the Chinese had kept closed in retaliation, as reported in another official letter from Ferreira do Amaral himself (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino - Overseas Historic Archive - Bundle 1 - Miscellaneous - Room 12).

Once the Barrier Gate was closed, the city was deprived of its supply of provisions, and this was one of the weapons the mandarins used to force the Portuguese entities to obey their impositions.

These drastic measures and the interests affected by them, so wounding to Chinese pride, can perfectly explain the murder of Governor João Maria Ferreira do Amaral by the inhabitants of the village of Mong Há. Aside from this, however, we have learned, from the then head monk at Kun Iam Tong Buddhist monastery, Wai Ian, of a poem attributed to the Mandarin who planned Ferreira do Amaral's death.

Fearing reprisals after the Portuguese occupation of Passaleão (a small Chinese fortress near the Barrier Gate) and all the other events that occurred in this dramatic period of the history of Macao, many Chinese inhabitants of Mong Há whose meadows and houses had been destroyed emigrated to neighbouring China.

In the meantime, in the village, conflicts and misfortunes worsened; the old inhabitants who stayed believed that Kwai, evil spirits, took shelter in the western zone of the settlement, particularly in the old Largo do Arvoredo, which has since disappeared.

Many inhabitants of Mong Há, who had left the village on the occasion of Governor Ferreira do Amaral's death, never came back. Successive and notorious typhoons, like those occurring in 1836, 1854, 1862, 1867 and 1874, destroyed fields, houses and trees. The streets the Portuguese were building after expropriating houses and meadows, were increasingly reducing the number of farmers, a consequence of the loss of space... The city was growing by destroying the countryside.

On the 20th December 1862, after a terrible cholera epidemic, a new and terrifying fire swept through the village, the second most calamitous fire Macao had ever known, second only that which had destroyed most of the Bazaar, right in the heart of the Christian city62.

In 1864, new taxes forced more inhabitants to emigrate. This represented one of the last and most fearful blows the village of Mong Há had undergone.

Old houses of the village of Mong Há at the time of expropriations.

Old houses of the village of Mong Há at the time of expropriations.

In 1873, several streets were completed in the lands of the Campo63, crossing through the settlements that had multiplied as a consequence of the strong attraction of the Christian city. This had once been the point of convergence for farmers and traders, particularly coming from the surrounding regions, eager to earn higher profits and better wages, or simply wanting to escape the waves of riots in the southern provinces of China.

At this time, settlements that depended almost exclusively on horticulture were doomed.

In 1878, the whole area up to the Barrier Gate was already considered to be urban, according to the report of the governor of Macao at the time, Carlos Eugénio Correia da Silva (Paço de Arcos)64. But the final and decisive blow to the village of Mong Há came in 1901, when Governor Jose Maria Horta e Costa declared it to be "urgent, to the public benefit, to expropriate of the buildings, hovels and huts located in the meadows of Mong Há" (B. O. no. 30 dated 27/07/1901).

By analysing the dates of the reconstruction works and of the most frequent and significant offerings made by the believers in the temples of Mong Há, we can construct a chronology of the great scourges that terrified the more credulous population. In 1848 Macao was devastated by a terrible typhoon, as it was subsequently in 1848 and 1871. The former also represented the final stretch of the hated Portuguese governor's administration. However, the reconstruction of temples and chapels carried out after 1869 may be related to the great flow of refugees who moved to the village to escape the Peng Lam riots and the continuous political upheavals in China.

On the other hand, the interregnum between 1821 and 1862 seems to be related to the exodus of many inhabitants of Mong Há when the Christian city began to extend outside walls, following the actions of Ferreira do Amaral. In 1909, the newcomers who were running away from the 1878 riots in the Chinese territory may perhaps explain the new offerings.

The 20th century was characterised by the decline of the village: earthquakes, typhoons, expropriations, a second fire and the urbanisation plans of Governor Tamagnini Barbosa. The inhabitants of Mong Há, among whom the farming population was decreasing the most, feared that the dissatisfied spirits living in the mountain and in the Largo do Arvoredo were causing all these calamities. The villagers believed that many spirits had been driven out from their graves to make room for the new streets, and, eager for revenge, were bringing them all that ill fortune. As a sign of their devotion, they decided to take a collection to have the most recent temple of the village built and the oldest one enlarged. It was then, in 1918, the 34th year of Guang Xu, that the Seng Wong chapel was built and the Kun Iam Ku Miu temple enlarged. Yet, Seng Wong, the "God of the Cities", the protector of the Chinese settlements, close to the kind-hearted Goddess of Mercy who had brought to Mong Há the prophecy of its future economic development, which the arrival of the "Western Barbarians" had brought to fruition, was of no use to the declining village.

The expropriations carried out in 1901 proceeded almost with no interruption.

Finally, in 1902, the fields of the village were expropriated so that the avenue named after that governor could be extended up to the Estrada Coelho do Amaral65. These were not easy transactions, since the Chinese lived by the fruits of these fields and did not want to leave them. It was then that the millionaire Lou Lim Iok intervened. He acquired most of the properties in which the Government was interested as if for himself, but only actually occupied a small area, on which he built a small mansion and famous garden (which would be acquired in the 1970's by the Government of Macao for tourism purposes)66.

Many Chinese, even today, blame their compatriot for this.

The Mong Há inhabitants were naturally alarmed at the invasion of their village by the Western barbarians. In 1874 (4th year of Kuong Soi), according to an inscription on an engraved tablet hanging in its inner courtyard, a temple dedicated to Sin Fong was built in the new San Tei landfills so as to protect the westerly access to the village. In 1918, in the 34th year of Guang Xu, the Temple of Seng was built more of a shrine than a temple, attached to the oldest local sanctuary Kun Iam Ku Miu, which was also the object of enlargement, according to an engraved stone existing at the site.

But Seng Wong, the protector divinity of the enclosed cities, close to the kind-hearted Goddess of Mercy, who had brought to Mong Há the prophecy of its future economic development and which the arrival of the Portuguese had brought to fruition, was of no use to the decaying village.

By the first decade of the 20th century, the village of Mong Há was but a lifeless settlement. Horticulture had practically ceased. In the village there were only a few houses, most of them mere huts and rudimentary brick houses. Yet, in the wider areas located to the south of the houses, there were still cultivated lands. Simultaneously, green areas began sprinkling the periphery of the city.

Those last houses were the ones we could still find in Macao in the 1950's-1970's.

Late in the last century, there were 5 Chinese villages or settlements in the suburban districts:

1. Long Tin Chun or Dragon Meadow Village, located, during the 1950's-1960's, in front of the so-called Flora Barracks, on the site of the Rua Alves Roçadas, Rua Leôncio Ferreira and Rua António Basto.

2. Chu Tau Chun, or Pig's Head Village, named after the rocky outcrop in the shape of a pig's head, which was in the Rua da Pedra, behind the Camões Grotto, to the north north-west.

3. Sa Kong, the Sandbox, of which only the Travessa dos Lírios, near the Red Market, was left in the 1950's-1970's.

4. The Santi settlement, with the Sin Fong and Lin Fong temples, which ran from the Estrada Coelho do Amaral to the Estrada do Istmo. In 1905, 67 it only had ten buildings, two public wells, two Chinese temples and one police station.

5. Mong Há Chun, with the two temples of Kun Iam, Hong Kong Miu or Ou Chan Kuan (Kong Ngau Kai) and the S. Francisco Xavier School; it ran from Rua da Bandeira (Flag Street) to the Largo da Pagode (Pagoda Square).

Laying out the new streets.

The Cadastral Survey of Macao Public Streets by Euclides Honor Rodrigues Viana (1905), 68 reports that, in that same year, Mong Há still comprised:

1. The Largo do Arvoredo (Su Sam Lei, or Grove Square, had four buildings and eight huts, and was situated on Rua do Norte (North Street).

2. The Largo do Pagode de Mong Há (Mong Há Miu Chin Tei, or Mong Há Pagode Square) had four buildings; it ran from Rua da Bandeira (Flag Street) and Rua do Touro (Bull Street) to the road near the Protestant Cemetery (now called the Cemetery of our Lady of Piety of Mong Há).

3. Largo das Tábuas (Pan Cheng Kong Tei, or Plank Square), had ten buildings and a side gate.

4. Estrada de Mong Há (Mong A Ma Lou, or Mong Há Road), ran from Ferreira do Amaral Road to the Mong Há Pagoda.

5. Rua das Amas (Ma Kai or Nursemaids Street) had seven buildings and two huts; it started at Rua do Touro and ended in Travessa dos Velhos (Seniors' Alley).

6. Rua da Bandeiro (Kei Kai, or Flag Street), had 14 buildings and a side gate; it started at the Mong Ha Pagoda Square and ended at Rua do Touro.

7. Rua da Cana (Cane Street) was located in Long Tin Chun and was known in Chinese as Long Tin Seac Kai. It had 13 buildings and six huts, where the Travessa do Carneiro (Sheep Alley) was located.

8. Rua das Hortas (Tin Kai or Garden Street), which had 21 buildings and a public well, was located along Rua da Bandeira, and gave access to the Fields.

9. Rua de Long Tin Chun (Long Tin Chun Kai, or Long Tin Chun Street) had 12 buildings, one back gate and two public wells, it started at Estrada Adolfo Louriro and ended at the Avenida Horta e Costa.

10. Rua do Norte, or North Street, known in Chinese as Pak Pin Kai (a literal translation) had 15 buildings, one pagoda (Kun Iam Tong), and one public well. It started at Rua do Touro and ended at Estrada do Istmo (Isthmus Road).

11. Rua do Passadiço, (Tong Ku Kai, or Corridor Street), had four buildings and one side gate, and was the location of the old temple (chi tong) of the Ho Family.

12. Rua do Rebanho (Kuan Toi Kai, or Flock Street), was located on the outskirts of Mong Há, in Sa Kong, the hill that residents used as a cemetery. This street had 44 buildings, a side gate and one hut. It started in Avenida Horta e Costa and ended in front of the Rua de Lucao.

13. Rua do Touro (Kong Ngau Kai or Bull Street). In olden times, this and the Rua do North were the most important streets in Mong Ha. In the early 20th century, the Rua do Touro only had ten buildings and one Chinese temple, the On Chan Kuan (now called 'Hong Kong Miu'). This street ran from Rua da Bandeira to the Mong Há Pagoda Square.

14. Rua da Várzea, or Meadow Street in Long Tin Chun. On this street, which descended from Mong Há to the western slope of Guia Hill, there was a small shrine dedicated to the local divinities, the protectors of happiness, for which reason it was also called Fok San Chak Kai. It had seven buildings, three side gates, and one cross street: the Travessa do Carneiro.

SIDE STREETS (Travessas)

15. Travessa do Balsamo (Veng On Sec Hong or Balsam lane), with 10 buildings, ran from Largo das Tábuas to Travessa do Búzio.

16. Travessa do Búzio (Kop Hung or Shell Lane), with 21 buildings, ran from Travessa do Toucado to Beco dos Pássaros, Bird Lane.

17. Travessa do Cano (Hang Ku Hong, or Pipe Alley) (in Long Tin Chun), had only 1 building and 12 huts, and was near Rua da Cana.

When we arrived in Macao, we settled in Mong Há. We lived in a two-storey house on the Avenida Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida, at the comer of the avenue known in Chinese as Nga Lin Fong (Avenida Ouvidor Arriaga), beside the old Sok Kei School.

From the balcony of our house we could see the Kun Iam Temple and a large marshy wasteland, stretching up to the "Barracas Metálicas" (the "Metallic Huts") on the other side of the avenue in front of the Bairro Albano de Oliveira, a district comprising two-floor dwellings which unfortunately no longer exist, but which were inhabited by Portuguese officials (both European and local).

This explains how, very soon, we discovered and studied the Lou Lim Iok Garden in the 60's, the small Kun Iam Chai or Kun Iam Ku Miu temple, the still imposing Lin Fong Temple and the Hong Kong and Sin Fong temples; we visited the chi tong (ancestral halls) of the Cheong and Ho families and entered the village of Mong Ha via the Rua dos Lírios.

Here the people told us old stories, demonstrated their traditional cuisine, showed us the drains covered by perforated slabs, the old well in the over-elevated Pátio Iong Loc where the whole family of an wealthy carpenter had lived; they took us to Rua do Caracol (Curlicue Street), Rua do Pano (Cloth Street), and Rua do Gafanhoto (Grasshopper Street), and spoke to us about the terrible kwai of the Largo do Arvoredo.

However, in the middle of the 20th century, the old topography of the village was practically unrecognisable.

Descending to the Travessa do Búzio, which was shaped like two frog feet, by way of six irregular stone stairs, we came to a small dead-end alleyway, corresponding to the old Largo das Tábuas, where some carpenters lived, the boards they handled and sold being stacked up at their doors.

Next there was the old Pátio Iong Loc, where the whole family of the entrepreneur Fong Song lived. Heading westwards, we entered the Travessa do Pano, which evoked the old family of Fukien, whose surname was Pou.

We walked along the Travessa do Gafanhoto, still very narrow and short in the 60's, and the Beco do Caracol, which led to the Rua Madre Terezina. The Travessa do Bálsamo and the Beco do Botão (Button Lane) intersected, rounding small houses and apparently dateless liu chai. Still heading southwards, we passed two old two storey buildings in the classical style, and arrived at the Travessa do Colchete which gave access to the other edge of the Pátio Iong Loc.

A street from what was left of the village of Mong Há in 1960.

Something was also left of North Street, Passadiço Street and Bull Street, which led to the Travessa do Pastor, which still existed though it had been transformed, and to the Pagoda Square, from the front of which the imposing Chim Fong house had already disappeared69.

When entering the village by the Travessa do Búzio and turning right, we would pass among old houses until we reached a block of new buildings, whose façades lined up along the Rua Madre Terezina. Rounding the last old block and turning left, we would find the Travessa do Bálsamo, which was crossed by the Travessa do Gafanhoto, the Travessa do Búzio and by the Beco do Botão. Continuing straight, we would pass two old two-storey buildings in the classical style, and arrive at the Travessa do Colchete which gave access to the aforementioned Pátio long Loc, where a deep well supplied the neighbourhood with clear sweet water. By descending its 5 rough stone steps, we arrived at a square enclosed by modem buildings: the old Largo das Tábuas.

Doubling back, we would reach again the Avenida Coronel Mesquita by going up an uneven ramp where we could find granite blocks of old demolished buildings.

From what was left of North and Bull Streets, absorbed by the Avenida Coronel Mesquita, remained the Amas and Pastor cross streets and the Travessa da Tecedeira where some inhabitants talked of a contiguous alley that, in 1925, had been on the left of the Police Station No. 6 of Mong Há, and which had contained only a few huts.

Looking at the old maps of Macao we can easily see how difficult it is now to use them to try to determine, even if approximately, the location of the houses of the Mandarin and of the most wealthy inhabitants of the village of Mong Há.

We presume such buildings were located in the area covered by the village, probably occupying wasteland that had not been tilled, on this side of the Mong Há swamps (which are also not demarcated on the old maps)70. Certainly, this area was close neither to the walls of the Christian city nor to the artificial canal of Patane, whose filthiness was something that such prestigious inhabitants would not stand.

However, in the 60's-70's we visited two beautiful houses, made of small bricks, located more or less in front of the Kun Iam Tong. It seems they belonged once to the old Chun or Cho family, whose descendants still lived in the vicinity of the Seminary in the São Lourenço neighbourhood. Another old house, Chinese-style, certainly owned by a wealthy family, was located at the intersection of Avenida Conselheiro Ferreira do Amaral and the Estrada Adolfo Loureiro. It seems that, later on, it was included in the great and famous Lou Kau or Lou Lim Iok garden. Actually, we believe that it was the millionaire himself who had it built, since he would certainly have located it inside the huge walls that could protect his property from prying eyes.

As for the house of the last Mandarin of Mong Há, the inhabitants of the village believed that it had been located in the palatial house of Tong Lai Chun, whose property had been largely occupied and transformed by the Madres Canossianas, the nuns who built their Santa Infancia and S. Francisco Xavier asylums there. In fact it was that site which some elderly inhabitants claimed was the old location of the Macao chi tong.

The study carried out on the Mong Há chi tong also provided some data on the most important families of the village.

The chi tong, though not exactly temples, were buildings dedicated to ancestor worship. They consisted of an altar or niche where the steles of the deceased members of the family were aligned. Their spirits were thus perpetuated and appeased with offerings made on the dates the Buddhist calendar consecrated to the worship of the dead. They are commonly known as "temples of the ancestors".

In the village of Mong Há there used to be the chi tong of the Ho, Chan, Hoi, Cheong, Sam and Pou families, all them in the neighbourhood of Kun Iam Ku Miu, that is, in the central zone of the settlement, which was severed by the planning and building of the Avenida Coronel Mesquita.

In 1954, the chi tong of the Pou family had been demolished a few years earlier and was relocated in front of No. 4 Rua Madre Terezina, a street that leads to the Avenida Coronel Mesquita, just facing the Kun Iam Ku Miu.

The other chi tong were located in the vicinity of the present Avenida Ouvidor Arriaga, except for the chi tong of the Sam family.

The chi tong of the Ho family had been demolished on the occasion of the first major expropriations, but it was rebuilt on the site where we found it in the 60's, outside the Avenida Coronel Mesquita alignment, between building nos. 34 and 36.

It was built of small bricks, in the typical style of old Chinese houses, shaded by what was left of a slender-leaved old bamboo thicket, with a façade covered in rather deteriorated stucco, and two effaced poems on either side of a partially disappeared old fresco. Over the door, the following Chinese characters were engraved in the granite:

HO SI JUNG CHI

(Ho Family ancestral hall)

Close by could be seen some stone steps of an old street or house, probably of the old North Street. This chi tong, like that of the Sam family near it, was no longer used for the purpose for which it was built. They were only meant to perpetuate the "seng" (surnames) of two of the most important founding families of the settlement of Mong Há. In fact, the chi tong of the Ho family served as home to a humble family. They allowed us in and we could see, at the back of the central compartment, the altar with about thirty plates, grown black with time and the dust covering them, aligned in two successive layers, which the occupants respectfully maintained. These were the steles of the Ho family, arranged according to the traditional chou mou order.

The start of urban development in the old zone of Mong Há. The cultivation of meadows can still be seen in the photograph.

Ahead, on a sacrificial table now faded of colour, a set of two vases, two chandeliers, and one perfume pan made of light green glazed terracotta attracted our attention. There were no aromatic substances or candles, nor even oil lamps. There was no light flickering on the altar. There were no offerings. The steles were kept as a sign of respect,since the steles are the homes of the spirits they represent. And the womenfolk above all would not take the risk of challenging the world of darkness.

On this altar we could also see a plate, once probably red, with three almost illegible characters in black:

SIN FONG TEMPLE

When the village grew, as a consequence of the many refugees from China who took shelter in Macao in the second half of the 19th century, the first landfills began to encompass the peninsula. To the south-west of the village, near one of its side entrances, was San Tei (literally, "New Ground" or "New Land"). It was on this easily accessible site that a new temple was built in honour of Sin Fong, a protective divinity.

This temple goes back at least to the 4th Year of Guang Xu (1874), since some of the offerings found there have that date engraved on them.

Both this temple (Sin Fong Miu) and the Lin Fong Miu, which was previously on the waterside and frequently flooded, did not exactly belong to the settlement of Mong Há, but rather to the marginal settlement called Santi (or San Tei).

SAN TEI HÓ PIN CHÜN

Lost in the confines of the old village of Mong Há, among the few old houses that still remain among the more recent buildings, the Sin Fong Miu can be found on the western side of the village at the end of the present Travessa Coelho de Amaral. The narrow street at the back of the Lido Cinema, bordered by an old wall, still displays in its uneven stone pavement the perfectly round flagstones that once covered the old gutters. These already had a different use at the time since formerly, both the wall and the facing landfills, which were already crowded with houses by the middle of this century, did not exist.

This temple seems to have been built in the reign of Dao Guang, over a hundred years ago, according to the inscription on the sound plate, a piece that must had been installed when it was founded. However, all old traces are gone except for that teng, a hanging iron sound plate in the inner courtyard, almost eaten away by rust, perhaps longing for the old sounds. The whole temple aroused compassion. Poverty. Nothing but the alms of the humble inhabitants of the neighbourhood accounted for its maintenance. Two refugees, a mother and her daughter, took care of the small temple, which, in spite of its impoverishment, was spotlessly clean and well-kept.

The temple was decorated with curtains in a Chinese flowery cretonne, costing little more than a "pataca" a yard, garnished with clashing hand-sewn spangles, together with the fan, laudatory strips also made of cotton cloth. As for the statues of the divinities, they were wood engravings garishly repainted, making it difficult to guess their age. The keeper explained that the temple had been robbed of its valuables, showing me the empty place - which looked more like an old blocked up doorway because of the base step - that had once displayed the plaques of the temple's benefactors. Once, five items had been stolen, among them an incensorium with old engravings which at the time was in the second chapel, and the statues of the first chapel. Nevertheless, the divinities' powers were so miraculous that the keeper did not realise that they had been stolen since their images continued to be seen in the respective niches. Only one of the statues, that representing the divinity at the entrance of the temple, to whom the mothers of boys with a natural propensity to steal (so-called teddy-boys), would pray for their sons to change, had not been stolen. It had become too heavy. Nobody could move it. Only later on, when the police came to bring some of the stolen items back, did the credulous keepers become aware of what had happened.

The old stone lion at the door, showing deep signs of erosion, seemed to be out of place. It is possible that it had been taken from another abandoned temple or house where it had left behind its symmetrical complement. The temple was painted light green and, in defiance of time, on one wall a low relief in stucco had been preserved, a delicate work in which we could identify peonies and plum blossoms. This was, indeed, the most beautiful work in the whole sanctuary. The granite foot panel, the door-jambs and the low relief stucco panels, where we could guess at, rather than see, a rocky landscape where flowers and foliage prevailed, really bear witness that the first construction of the Chinese temple was truly old and inspired by devotion.

The great fire in the bamboo plantation was but the first blow to the village of Mong Ha. Some believed it had been caused by the carelessness of devotees burning votive papers, but others put the blame on the Portuguese, saying it had been part of their improvement plan; still others believed it had been started in revenge by the rival villagers of Sa Kong. Other setbacks followed the fire, such as the death of the Governor Ferreira do Amaral, which impelled some families to emigrate outside the Barrier Gate fearing retaliation. However, it was without doubt the expropriations and the levelling operations carried out by the teams of the Public Works Department which were the final blows to the old village of Mong Há.

All this valuable architectonic heritage of Macao which the village of Mong Há represented has been forgotten. It has been lost. It has been lost, like many other jewels built by the Portuguese and the Chinese, side by side, which were living landmarks of history. Unfortunately, those who value capital more than other much more precious assets very often envisage progress as growth. Recalling these values is derogatorily called "revivalism" by many people: as if revivalists can be the witnesses of memory.

Translated from the Portuguese by PHILOS - Comunicação Global, Lda. www.philos.pt

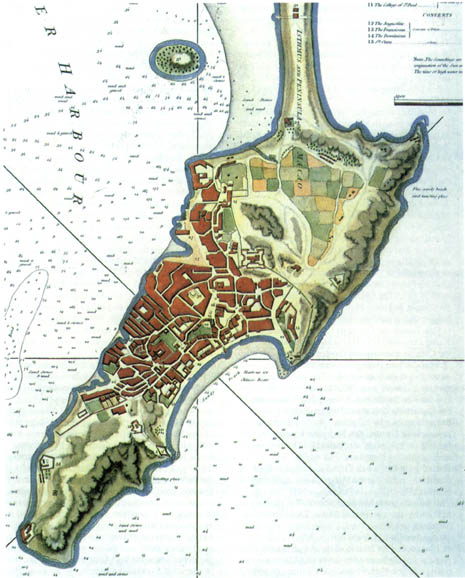

The old lagoon on the brink of extinction.

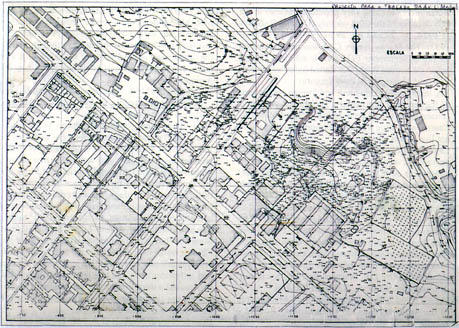

A detail of a map of the city and the Harbour of Macao by B. Baker (reprint by the Direcção dos Servicos de Turismo, 1986).

We can see the development of the village of Mong Há, the extent of its fields and the importance of the Temple of Lin Fong late in the 19th century.

Blueprint for the layout of the Avenida Coronel Mesquita.

Map of classified heritage sites in Macao peninsula, according to the list contained in Decree Law 83/92/M. (Produced by the Board of Cartography and Records Services for the Cultural Heritage Department of the ICM)

NOTES

1 Father Manuel Teixeira, Macau e a sua Diocese [Macao and its diocese]. - I - Macau e as suas ilhas [Macao and its islands], 1940, p.73 (quoting Peter Mundy - The Travels of Peter Mundy, Hakluyt Society, London, 1919, Vol. III, Part I, p.164).

2 Chok pou is an archive, handed on from generation to generation and sometimes recopied, in which old Chinese families registered the major events of their lineage, especially in ancient times, when a branch separated itself from its clan. This file was kindly made available to us by the special courtesy of the then head of the Sam family, Master Sam Hoi, a traditional doctor living in Macao, in Estrada Coelho do Amaral, no. 6.

3 This is probably a distortion of the name of general Man T'in Cheong, who escorted the last Emperor of the Song family in his escape to the southern provinces where, in 1279, he organised, together with Cheong Sai Kit, the last line of defence. Man T'in Cheong became a mendicant bonze who, following his Emperor's death, began wandering the southern provinces. This happened when the victorious Mongolian armies occupied the whole area of Guangdong and Fujian, imposing their rules and spreading terror among the supporters of the previous dynasty. The founders of the walled village of Kam Tin, in the New Territories of Hong Kong, were immigrants as well, escaping from the Mongolian troops at the end of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). This leads us to accept as authentic the events registered in the chok pou records of the Sam family.

4 This old use of the Family Cancellation by elimination of close relatives was one of the most drastic punishments, in line with what the Chinese considered to be most sacred, according to the Confucian doctrine and their religious conceptions: the perpetuity of the name, which granted their deceased ancestors eternal peace.

5 Literally translated as "wind and water", it represents an auspicious and more or less supernatural current. Today, it is regarded as ancient empirical knowledge of the electromagnetic fields, since geomancers or dowsers used a complicated compass. The Chinese believed that the location and orientation of sites, of the houses, or even of graves, had a significant influence on their occupants and relatives. This is a conceptual vestige of ancient chthonian cults.

6 The present Zhongshan, named after Dr. Sun Iat Sun, alias Sun Zhongshan.

7 Kam Kok - the old name of the highest point of the hill of Mong Há.

8 An old Chinese practice consisting of building houses on sunny hillsides, like a cascade, thus avoiding them overshadowing each other.

9 Heong San On Chi, pp.281 and 323.

10 In common language it was known as Ham Cheong Mei, owing to the salt content of its waters. This branch of the river entered the peninsula up to the 3 Lamps Square (Sam Ngan Tang).

11 Contemplates the Sun in the East.

12 These hills make a single mountainous arch known by the name of Mong Há Hill. This arch is only cut in the east by two small elevations - Montanha Russa (old Bela Vista Hill) and D. Maria, whose highest point does not exceed 59 meters.

13 According to an old legend quoted by Jaime do Inso (Cenas da vida de Macau, Cadernos Coloniais VII(Scenes of Macao life, Colonial Books) - no. 70, p.23, Ed. Cosmos, Lisbon) this may have happened among the fishing people of Barra, where an image of Kun Iam appeared floating over a lotus flower. This explains the auspicious name given then to Macao: "The Land of the Lotus".

14 This temple is the existing Kun Iam Ku Miu - see Ana Maria Amaro - Kun Iam Ku Miu, sep. of Boletim Luís de Camões, nos. 4 and 5 of April and May, Macao, 1967

15 Cangcong, local Macanese name of hong choi or tong choi, Chinese name of Ipomea aquatica.

16 Since the oldest times in China, the cultivation office had always been a community effort, since it required a significant labour force.

17 The forest started being settled in 1877 (Boletim Oficial of 27th of November 1879) under the aegis of governor Tomás de Sousa Rosa.

18 The rank depended on the level of exams a candidate passed - the district, province or nation-wide level -and on the score he acheived on each exam, which would be posted on a ranked list.

19 Heong San On chi - Descrição Monográfica do Distrito de Héong San e Ou Mun Kei Leoc (Monographic Description of Héong San and Ou Mun Kei Leoc District) - Descrição Monográfica de Macau (Macao Monographic Description). The works related to the village, according to some descendants of old families living there, were about 200 years old. Some informers report that the grand palatial Chinese style house, which had been demolished to build the Irmãs Canossianas School, was probably the Mandarin's house.

20 This authority was probably transferred to Macao in the 17th century, when the development of the Portuguese city justified it. According to Chinese sources, thanks to the development of the city, the increasing growth of the Chinese population and the consequent proliferation of more or less serious cases involving them, in the 8th year of Kin Long (1743) the prefecture position of Siu Heng was replaced by the Civil and Military Prefect of Coastal Defence. His head office was located in the walled city of Chin San and he directly reported to the District Magistrate's Assistant, whose head office had been transferred to Mong Há (Ou Mun Kei Leoc). According to the Chi Un report, the district magistrate, Leong Man Chon, of the Un Seng rank, who had come to Macao in the 19th century to study the problem of the delimitation of the frontiers, settled himself in Mong Há to deal with Chinese business, from the 8th year of Qian Long's reign (1743) up to the 29th year of Dao Guang (1743), (Heong Sam Un Chi, p.284). It is almost impossible to accurately establish the location both of his house and the office where he worked, though some old houses, built with small bricks, survived the demolition that followed the expropriations.

21 Tou Tei, one of the farmers' protectors, along with San Nong, the Divine Farmer, the third of the Three Emperors of the first and legendary dynasty of Chinese history (2205-1765 BC)

22 Celestial Concubine, heteronym of Neong Ma or A Ma.

23 Lin Fong Miu Isthmus Temple. The existing Kun Iam Ku Miu would have still been a small shrine at that time.

24 Maybe because this was the second temple to be built in Macao, the Tin Fei, (the divinity also known by the name of Neong Ma, whose first temple had been built in Barra), was called, for a long time, the "New Pagoda".

25 The present, huge Mong Há temple - Kun Iam Tong, one of the favourite sites of tourist guidebooks. In Tin Kai's reign (1621-1627), the Pou Chai Sin Un monastery already existed, since in the third year of that reign, according to a memorial stone at the site, a piece of land next to it was acquired, which is now the cemetery of the bonzes.

26 There appears to be some disagreement here: the reign of Zheng De covered the period between 1506 and 1521, yet the year of Teng Mei of the closest sexagenary cycle corresponds to the year of 1547, which falls during the reign of Emperor Jiajing (1522-1567).

27 Ou Mun, "Gate of the Bay" or "Gate of the Anchorage", is the name given to Macao owing to the conditions of its harbour. It should be stressed that only following the Yuan dynasty (1280-1367) did this term begin to be used in China to refer Macao in maps. Previously, this peninsula was known as Ou Kéang (Oyster Mirror), as the work of Héong San Um Chi reports.

28 This information corresponds to that reported in Tábuas das Crónicas dos Ming (transl. by Father Manuel of the Portuguese Mission of Canton, Siu Heng, West River, China), whose manuscript can be found among the documents of the estate of João Feliciano Marques Pereira (Biblioteca da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa - Library of the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Reserved Section).

29 Quoting Father Gaspar da Cruz, who stayed in Canton in 1556: "(...) The Chinese who had contact with the Portuguese, and some Portuguese with them, started to behave badly, stealing, robbing and killing people. (...)", in Tratado das Couzas da China e de Ormuz, p.27.

30 Rafael Perestrelo (?) - This is an hypothesis based on the Chinese transcription (homophonous).

31 "Lampacau", in Portuguese sources.

32 According to the book Ou Mun Kei Leoc," the ground rent for of Macao was 500 taels in silver which was collected by the district of Heong San." According to the Portuguese documents, the ground rent seems to have its origin in a "peita" (bribe) given to the mandarin of Canton, this being the reason why this fee was called "peita" or "peitada". The rent is still an issue among historians.

33 Registered in the Fu Lek Chun Su - Complete Books of Statistics - printed in the Meng dynasty, in the reign of Wan Li (1573-1620).

34 This official name had been accorded to the City of Macao by the viceroy of India, Dom Duarte de Menezes, in 1568.

35 Heong San Un Chi, Book Ⅶ, p.8.

36 A. Ljungstedt, - An Historical Sketch (...), Boston, 1836

37 General name given to the slaves taken from the east coast of Africa. Father Francisco Cardim - Descrição de Derrota dos holandeses (Description of the Dutch Defeat) - 24th of June 1622 and Father Francisco de Sousa (1546) - Oriente Conquistado (The East Conquered) - and Papéis de D. Francisco de Mascarenhas (Notes of D. Francisco de Mascarenhas) - manuscripts of the District Library and Archive.

38 Manuscripts of the Biblioteca da Ajuda (Ajuda Library) - Jesuítas na Asia, (Jesuits in Asia) and Father Montanha - Aparatos para a História de Macau (Materials for the History of Macao), Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (Overseas Historic Archive).

39 C. R. Boxer - Macau na Época da Restauração (Macao during the Restoration Era), Macao, 1940, and Father Manuel Teixeira - Os Macaenses (The Macanese), Macao, 1981.

40 The Bazaar was built in 1788 - Memórias sobre a franquia do Porto de Macau (Memories of the franchises in the Macao Harbour) - Manuscripts by João Feliciano Marques Pereira - Library of the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Reserved Section.

41 "Campo" - the Portuguese and Anglo-Indian name given to the land outside the walls of a city.

42 Also inappropriately called Charil Hill, a wide spread distortion of the first designation of Chaúl Hill, named in memory of the hill of the Indian city of that name, which resembled the hill of Guia.

43 The city wall seems to have been built between 1556 and 1623. (Manuscripts of the Biblioteca and Arquivo Distrital de Évora; Papéis de D. Francisco de Mascarenhas, sheets 178, 179 and 184).

44 Even in 1960, a domestic servant in Macao earned the equivalent of 150 - 200 a month, and a worker in a small factory, 5 to 10 a day.

45 A site near the Barrier Gate, in the Chinese territory, where there lived the magistrate with responsibility for Macao, who held a higher position than the Mong Ha magistrate.

46 In spite of the good market conditions offered by the city of Macao for horticultural products, large areas of land outside the walls, whose cultivation was more difficult, still looked desolate in the 19th century.

47 In the middle of the 17th century, the prosperity of the city of Macao declined. The Dutch assaults on the Portuguese ships, a consequence of their hostility against Spain, of which Portugal was a dependency in the period between 1580 to 1640; the collapse of Malacca; the disasters experienced in Japan and the expulsion of all the Portuguese and Portuguese-Japanese who lived there, as well as the suspension of all trade activity; and the war with Timor - all these problems destroyed both lives and goods, resulting in the need to take out successive loans and use Chinese funds. Only around 1720, when the trade with Cochin-China and Manila was established, did the territory regain a degree of prosperity.

48 This was, however, a transitory prohibition. Artur Levy Gomes - Esboço da História de Macau (Outline of the History of Macao), Macao, 1926 (2nd edition).

49 One of the causes of the decline in population, in parallel with the economic decline and the departure of many Portuguese, is explained by some historians by the fact that many girls in Macao chose to profess religion in that period.

50 A. Ljungstedt, Historical sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China (...), Boston, 1836. According to Cod. 278, sh. 2v of the Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa - Overseas Section - (quoted by Frazão de Vasconcelos in A aclamação de El Rei D. João Ⅳ em Macau (The acclamation of King João Ⅳ in Macao), sep. No. 53 of the Boletim Geral das Colónias, 1929, p.46), in 1643, there were in Macao over 2,000 Portuguese sailors. Domingos Maurício Gomes dos Santos, in Macau - Primeira Universidade Oriental do Extremo Oriente (Macao - The First Eastern University of the Far East) in Anais da Academia Portuguesa de História - Series Ⅱ- 17 -1968 - p.203 and subs.), quoting António Franco - Imagem da Virtude... (Image of Virtue) in O Noviciado de Coimbra (The Novitiate of Coimbra), I (Évora 1719 - p.682 and subs.), reports that in 1562, Macao had between 500 and 600 inhabitants and in 1'576, "5,000 souls, of which 800 are Portuguese in a desperate moral condition ", (quoting Fortunato de Almeida - História da Igreja em Portugal Ⅲ -History of the Church in Portugal Ⅲ (Coimbra 1912, pp.83 and 84). See also Levi Maria Jordão - Bullariam Patronaus Ⅰ (Lisbon, 1869, pp.243-246). This can be compared with what A. Bocarro reports: "850 married Portuguese with 3 to 6 slaves each, of which the best were the Kaffirs. A further 850 married men born in the territory. Many sailors. Many more bachelors fleeing justice." (A. Bocarro - Manuscrito da Biblioteca Municipal e Arquivo Distrital de Evora (Manuscript of the Municipal Library and Evora District Archive) - Cod. XV/2-1).

51 Gravestone encrusted in a wall of the northern wing of the old monastery next to the Lin Fong Miu, a space converted in 1967 into a primary school.

52 Horse racing became very popular in Macao in the first decades of the 20th century (Official Bulletins of 1924, no. 27 and no. 29 of 1930 and no. 19 of 1932). The Macau Jockey Club was inaugurated on the 6th of September 1931 and closed 10 to 15 days before the Second World War started (information from Reverend Monsignor Manuel Teixeira).

53 Yet, in 1830, the Portuguese and foreign populations of the territory registered a significant growth, a consequence of the prohibition by the Viceroy of Canton, according to which European women could not live in that city.

54 Lieutenant-Colonel José Luis Marques, Breve Memória acerca dos assinalados feitos dos dois heróis da autonomia de Macau - Amaral e Mesquita (Brief Account of the undertakings of the two heroes of Macao's autonomy - Amaral and Mesquita), Macao, 1920.

55 Chinese criminals were expelled to Macao, or chose that place to escape the Mandarins' justice. The Kaffirs escaped from their masters to the Campo and, once there, they carried out fearsome night time raids. The tradition of the cafre and cafra stories of the old Macanese most probably have their origin here (Manuscripts by J. F. Marques Pereira - Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Reserved Section).

56 Decree dated 20th of December 1845 - Manuscripts of the Arquivo Historico Ultramarino - Box 42 -Bundle 44.

57 Abridged from the Newspaper Revolução de Setembro (September Revolution), no. 1916, dated 2nd of August 1848, published by authority in the Boletim do Governo da Província de Macao, Timor e Solor (Bulletin of the Government of Macao, Timor and Solor), vol. Ⅲ, no. 20, dated 21st of October 1848.

58 Heong Sam Un Chi - Report sent to Beijing by Chong Chi Tong, Governor of the Two Guangs: Guangdong and Guangxi.

59 The rural villages of Mong Há and Long Tin Chun, at that time, still paid a tax to the Prefect of Heong San on their fields (per area of 4 keng?), houses and business profits, as reported in the Prefect's Office. In 1849, however, (29th year of Dao Guang), the Chinese magistrate that lived there to attend to the business of his compatriots was sent out of Mong Há and, from then on, moved to Pak Seak, in the district of Chin San - tr. from Heong Sen Un Chi, book Ⅵ, pp.9 and 10.

60 This oral tradition is reported in the chok pou of the Sam family, which for this very reason attracted us to consult it. The name registered in this chok pou is Sam Ma Mei.

An unpublished manuscript of a contemporary Macanese, Francisco António Pereira da Silveira (Resident collection of the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa), speaks of a Lin Chin Leong, as the probable murderer of Governor Ferreira do Amaral. However, the author of this manuscript accepts that this may not be the real murderer, although he has the "same name as the Chinese of Moha, whose father had seen his hut destroyed by the fire set in June by Amaral."

61 Ref. A 66/848 2716th - Macao, room 15 - 2nd Section - Miscellaneous, Bundle 1 - 1839 to 1858, Arquivo Historico Ultramarino.

62 1863 - The Chinese living near Macao, to the north- east of the Isthmus, organised a procession such as had not been seen the previous 40 years. With the prior permission of the higher authorities, they entered Macao and paraded through the village of Mong Ha and the Christian city for three days. They spent 40,000 "patacas" in decorative items, garments, umbrellas, palanquins and flags with graceful matte and golden embroideries, each costing 300 "taels". The procession involved over 1,000 Chinese, all from Shou Ui. They stayed in the city at the expense of the Chinese traders, no public disorder having occurred. It seems this procession had been organised to keep bad influences away and to allay the evil spirits that had caused a terrible epidemic of cholera in Macao and its the surroundings, which accounted for the death of at least a hundred people.

63 Estrada Nova de Maria Ⅱ (1,800 m); Estrada da Porta do Cerco (800 m); Estrada do Quartel do Batalhão de Infantaria do Campo da Guia (750 m). The Estrada da Porta do Cerco was built on the old track that linked that area to the village of Mong Há and which then branched off towards the city. It appears already in some maps of Macao from the 18th century (Report of the Governor Visconde de São Januário, Mss. of the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino).

64 Report of the Governor of Macao, Carlos Eugénio Correia da Silva (from the 31st of December 1876 to the 28th of November 1879), p.36. Reserved Section of the Biblioteca da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa.