HISTORY

LIMITATIONS

When we refer to remote historical facts, it is often difficult to guarantee the accuracy of details, the exact chronology and the locations where they actually occurred. Even contemporaneous accounts, where they exist, often differ in their accounts, varying the names and the dates they provide. Macao is no exception to this rule, as we discovered in attempting to write a history of the origins of architecture and urban development in Macao, following its development throughout the centuries. Various hypotheses have been put to us as to the exact year in which the Portuguese arrived on the peninsula and as to the origin of the territory's name. However, in this article we will not concern ourselves with all historical facts, but only with those which directly or indirectly influence Macao's architecture in its diverse aspects.

Given this limitation, we propose to merely sketch in broad strokes the history of Macao, returning to the time of the Discoveries, when the Portuguese expanded their little Lusitanian rectangle over the five continents, and thereby introduced hitherto unknown lands to the medieval world.

THE BEGINNING

Passing from one "discovery" to another, our ancestors arrived in India, and from there it was just a short step to the Far East, which had attracted them for so long. In the first half of the 16th century, Portuguese sailors had reached the shores of China, where a few merchants soon settled. In 1553, during the course of one of the typhoons typical of the region, a Portuguese ship put into a small fishing port in order to dry out, on land, the cargo which had been soaked in the heavy rain. When the natives were asked what this place was called, they answered "Ma Kok Miu", meaning "Temple of the Goddess A-Ma", because they thought that the question referred to the beautiful temple that was there at that time. If other possible explanations are disregarded, it is from this misunderstanding that the name of Macao is derived.

Aerial view of Lin Fong Miu, showing the courtyards.

Aerial view of Lin Fong Miu, showing the courtyards.

And so began a Portuguese presence of four and a half centuries in the territory. At that time the peninsula was significantly smaller than nowadays. The sea still lapped at the bases of the hills and the coastal profile was constantly changing due to the movement of the waters and the consequent erosion or siltation. There were only two small villages: Barra, which surrounded Ma Kok Miu, and Mong Ha, around the Kun Yam Ku Miu, as well as a small settlement close to the vegetable gardens of Patane and the little stream of the same name which flowed into the Inner Harbour. The riverine populations lived in their boats, either on the river or drawn up on the beaches.

The lifestyle of the first residents was certainly rather basic. Their buildings were no more than huts built of rushes. We speculate that these would have had a light structure of bamboo (a material which even now is widely used for the most diverse purposes) and would have been covered in straw, which was easily replaceable when necessary.

Feeling themselves to be established and making progress in their trading, the Portuguese soon began to replace such primitive materials with slightly more substantial materials: wooden walls covered with tiles brought by the very native merchants with whom they traded. Even so, the sense of precariousness remained, since none of them could help but remember the downfall of Liampo and Chincheu, which had been destroyed by natives, and from which only around five hundred Europeans managed to save themselves.

The history of the peninsula continued to unfurl, following Chinese history and, naturally, reflecting world history. Between 1555 and 1557, at the behest of the local mandarins and also in their own interest, the Portuguese waged war on the pirates who infested the Chinese coastline, killing and destroying and hampering trade. It is believed that the Portuguese poet Camões would have been involved in some of those battles, as at that time he held the position of "Commissary of the Deceased and the Missing" in Macao - a testament to the administrative organisation already existing then.

With victory having been won over the corsairs, Emperor Kia Tsing decreed that the Portuguese could stay in the territory where they had settled, granting them permission to erect the buildings necessary for their way of life. With the security that this situation brought, little by little a new architecture began to flourish, using bricks and roof tiles: in less than two decades the group of huts had disappeared and a settlement of appreciable size had grown up, surrounded by a "tranqueira" (a stockade of wood, as a means of defence), with a central road serving four irregular blocks of housing, and some public buildings.

The prosperity of Macao attracted the attention of other sea-faring countries, and various attempts at conquest were made, culminating in the Dutch attack of 1622, which was repelled by the city's defenders. It became imperative to build fortifications, even against the wishes of China. From 1607 Philip Ⅱ ordered the construction of city walls, recommending in 1614 that this be done without upsetting the Chinese authorities, who feared that the Portuguese forces would turn against China and only provide explanation or justification for their actions after the attack.

THE DECLINE

After a period of splendour and prosperity which we can call the "golden age" of Macao, especially with respect to its architecture, the city entered into decline from the end of the third decade of the 17th century. Various factors contributed to this situation, namely worsening relations with China (especially after the Tartars entered the country), the loss of trade with Japan and Manila, the constant skirmishing with pirates, internal quarrels, and fighting in Timor. (At that time, the greater part of the Macao economy depended upon Timor, based, as it was, on a monopoly on sandalwood which came from Timor and was traded in Macao. In 1688 a local chieftain rebelled against Portuguese authority and the fighting lasted for around fifteen years. This contributed greatly to the impoverishment of Macao in terms of both goods and men).

In 1684 the Chinese established a customs house on the peninsula. This was the Hopu Grande (large Hopu), in Praia Pequena, beside the Inner Harbour. Later, the Hopu Pequeno (small Hopu), a subsidiary of the former was built in Praia Grande on the Outer Harbour. Thus more taxes were levied on the impoverished inhabitants of Macao. In the last years of the 17th century there were only 150 Portuguese families in the city, compared with 600 families at the beginning of the century.

Faced with this situation, new building stopped and existing buildings deteriorated and could not be repaired due to lack of funds. At that time the city must have been a very sorry sight indeed.

The 18th century was no better. With the truce between Portugal and Holland in 1701, peace returned to the waters of Macao, but not to the city. Internal strife between the laity and the church, and within each of these groups, proliferated. To top it all off, great typhoons swept the peninsula, causing extensive damage. The waters flooded the city, and at times vast areas were under water, further contributing to the deterioration of the buildings.

The Chinese authorities, who had already expelled the Catholic missionaries and forbidden the propagation of the Christian faith within the Empire, stepped up the pressure on the Macao population. In 1749, among other things, the construction of new houses in Macao was forbidden without prior Chinese permission, and only a few works which were considered to be indispensable were allowed, such as the construction of a few Chinese temples.

Nor did the 19th century begin well. The English insisted on "helping" Macao, installing themselves in the city. The opium trade, which was fiercely opposed by China, was conducted from Macao by the English and Americans, which brought new problems. Some African slaves passed through the Portas do Cerco and behaved disrespectfully on the other side of the border, with terrible repercussions. The Chinese authorities continued to rule in the territory while promising to restore the privileges the people of Macao had previously enjoyed. The mandarins rained edicts on them, prohibiting everything from opening roads and building simple walls, to selling copper utensils to Christians or allowing them to ride in sedan chairs carried by Chinese. Meanwhile, a number of fires further aggravated the city's decline: one in the convent of Santa Clara, another in the district of São Paulo in 1825, another that destroyed part of the Chinese district in 1834, and the great fire which razed the new church of São Paulo in 1835, reducing it to the ruined façade which is preserved today.

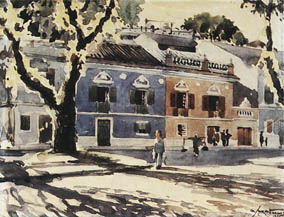

Largo do Senado.

Largo do Senado.

THE REACTION

However, the resurgence of the territory was imminent, due to external causes. The British East India Company controlled the flourishing opium trade, importing opium from the English territory of Bengal to a factory close to Canton, and relying upon the collaboration of Chinese traders despite the Imperial prohibition. Even after the monopoly of the Company had been broken, the opium trade continued, until, in 1839, the viceroy of Canton confiscated the drug and expelled the British from the region. Understandably, England could not tolerate such an affront. In 1840, it occupied Hong Kong and thus began the "Opium War." China was forced to recognise its technological inferiority, and, impotent before the modern military might of the westerners, was obliged to sign the "Treaty of Nanking" in 1842, granting rights and paying indemnities to the foreigners. This defeat of the Manchu dynasty reawakened national pride and led to the Tai-Ping uprising of 1850, which the Qing was able to suppress fourteen years later, with the assistance of their old western enemy.

Following China's loss of power, various countries occupied diverse areas of it, whether by means of protectorates or conquest of territories, and, obviously, the pressure on Macao diminished. Portugal was the only country with interests in the region which did not take advantage of the situation. On the contrary, in order to ensure that it kept possession of Macao and to define the limits of its territory, the Portuguese Government gave up its claims to the islands of Montanha, D. João and Lapa, in return confirming its ownership of the Macao peninsula up to the Portas do Cerco, and of Ilha Verde and the islands of Taipa and Coloane. According to a report in June 1872 by the governor Pedro Azevedo Coutinho, the territorial waters of the province of Macao were delimited as follows: to the north, both in the Inner Harbour and the Roads, by the mean parallel between Ilha Verde and Apo-Seac. To the west, by the edge of Lapa to its S. E. point, from there a straight line to the N. E. point of D. João, following the coast of this island until it meets the meridian in the Prata channel which passes through its N. E. point, then following this meridian until the coast of Von-cam, and from there along the coast of that island until the mean parallel of the bay formed by the S. coast of Coloane and Von-Cam, this parallel constituting the S. limit. To the east, the limit of territorial waters is determined according to the principles of international law. The land between the Portas do Cerco and the Passaleão was considered to be neutral.

Other factors also contributed to the new era of prosperity: the abolishment of the Hopu in 1849, thus ending payment of taxes to China; the arrival of rich Chinese merchants from Kwangtung province, who were fleeing from the rebellion in that region and who brought with them their capital and their creative potential to stimulate business; and also the liberalisation of gambling, which attracted outsiders who came and lost their money in the Macao casinos. Income from the respective taxes provided the funding for various works of public interest.

Finally, we should mention that the founding of Hong Kong had positive consequences for Macao, although there was one somewhat negative feature which might be deemed rather less agreeable: Macao did not regain its old privileges and power. Hong Kong evolved rapidly and combined all the aspects of development which can make a territory "great" - an excellent harbour, an airport, a good internal transport network, flourishing industry and commerce - all to the detriment of Macao, which now had to content itself with a modest second place. However, Macao today has witnessed a series of major works that are practically completed and in operation, such as the new Sea Terminal and Heliport of the Outer Harbour, the Macao International Airport, the new bridge to the islands (Amizade Bridge), the incineration plant on Taipa, the water treatment plant (WTP) in Macao, the deep water harbour in Ka-Ho (Coloane) and the new fishing port, not to mention the constant growth, both upwards and outwards, of civil construction.

URBAN PLANNING

SPONTANEOUS URBAN PLANNING

Urban planning, the organisation of habitable space in order to promote social life, constitutes one of the principal socio-economic structures of humanity, and varies according to models of civilisation. Primitive urban development in Macao followed the models of two civilisations coming into contact with each other for the first time: the eastern and the western. Each left its mark on the building of the new city which began as three distinct and isolated settlements and finally became organised into a single progressive space.

The Chinese buildings, as we will see in the following chapter, were traditionally surrounded by a palisade, which in later constructions became a high wall, enclosing the main house, the outbuildings and a relatively large open-air space. These compounds were haphazardly juxtaposed with each other, leaving small squares and narrow angular alleyways between them, which have lasted through the centuries, resisting subsequent urban development, and are still to be found today. In their turn, the westerners, alone in a strange and perilous land, installed themselves around churches and convents, systematically sited on top of the small hills, initially creating nuclei which were separated from one another. They adopted the Chinese principal of enclosed plots of land, combined with the system of streets lined with houses they brought from their homeland. One may well imagine how chaotic the urban development of the Portuguese areas of Macao was in those early times.

In the early decades of the 17th century various military fortifications were erected to defend Macao from prospective foreign conquerors, and for around two centuries their existence hampered urban expansion, which was limited by the strong city walls of lath and plaster. These walls linked the fortresses and were only broken at long intervals by gates opening onto the outer territories.

Within these limits, the city continued to develop, and those spaces which had been originally left free were progressively occupied. Steep winding roads linked the various zones. There were large squares in front of the main buildings and a frontage road was created along the Praia Grande where the most imposing residences were sited. The number of Chinese residential nuclei grew, still maintaining the traditional structure of Chinese villages. Between the church of S. Domingos and the Porta do Campo was the Great Bazaar, which can be thought of as the first shopping centre of the city. It consisted of various stalls, either open-air or with rudimentary sloping thatched roofs or in the shape of a Chinese hat. The merchandise could be spread upon the ground, in baskets or on crude portable tables. Among the stalls wandered animals peacefully awaiting their turn to be slaughtered for sale. Gambling - even at that time -had its place at various points throughout the Bazaar.

An early industrial zone, in the Rua do Chunambeiro, already had two manufacturing outfits by the middle of the century: a factory for making lime from oyster shells (locally known as "chunambo") and the famous bronze foundry of Manuel Tavares Bocarro. To these, other industries would later be added.

Due to the poor financial situation of the city, there was practically no development during the final part of the 17th century and the whole of the 18th century, and it was only from 1840 onwards, for the reasons already cited, that urban development recommenced. Having survived this difficult period, the territory began to grow anew.

D. Pedro V Theatre.

D. Pedro V Theatre.

The densely populated European nucleus slowly began to spill out from behind its walls, and when large stretches of city wall were later demolished, the whole peninsula was gradually taken over by new residential areas and their accompanying services. The diverse residential clusters, ancient and modern, slowly became interlinked, forming one single, continually expanding, urban area. The first landfill project took place in the Inner Harbour, between Praia Pequena and Praia Manduco. In the levelled - out zone thus created, ten well-ordered blocks of housing sprang up - the first partial development plan of the peninsula. The population of some 25,000 inhabitants around 1840 grew to about 65,000 by the end of the century, creating a demand for new residential districts.

The various plans of Macao which have been drawn up throughout the ages, from primitive perspective maps to the fairly rigorous drawings of the 19th century, allow us to trace the evolution of its urban development, the creation of successive land reclamation and the appearance of new districts. The coastline is altered, the wharves are built that delimit the waterfronts, a few cemeteries are created and green areas are planted in various locales. The illumination of the city began in 1871 with more than 2,000 oil lamps, which represented significant progress for the time.

Industrial development began in the 1880's, with the installation of fifteen fireworks factories, two glass and crystal factories, at least six silk spinning and weaving factories in various parts of the city, and others producing tea and mats. In 1866 a cement factory was opened on Ilha Verde.

Small progress? Indeed it was, but it was the start of a journey which would lead to the great progress of our city today.

The road system laid out during Ferreira do Amaral's government, which linked the central district to the northern streets, was successively amplified, modernizing the system of transportation to the Portas do Cerco and providing even more new areas for construction.

EARLY STANDARDS

The establishment of the Public Works Department in Macao in 1869 helped to reinforce the remodeling of the city, which benefitted from these services. A decree issued on 31-12-1864 had defined the relationship between road width and building height, and this was taken as a starting point in the report of the Commission set up by a provincial order of 28-7-1833, which was charged with studying the "material improvement of the city."

The measures recommended in this report can be understood as a statement of intent regarding urban development, but not a true urban development plan, which was never drawn up, although it was expressly called for:

"As a preliminary to any important improvement carried out in Macao in future, it is absolutely indispensable and imperative to immediately draw up a general plan of the future city, which should be based on a meticulous plan of the present city" (We had to wait eighty years for the first master plan of Macao to be made!).

The Commission based its recommendations on the work of the Directorate of Public Works and the Medical Board, as well as on direct surveys of the various zones of the city. Its concern focused on the following twelve points:

1. Width of roads and height of buildings - This was governed by existing legal precepts, which were generally difficult to enforce in already built up areas. The roads were "tortuous, narrow, varying in width almost with every building", and also problematic was "the direction they took, separating by wearying meanderings two locations which nature has placed close to each other". On this last point, special attention was paid to the need for an "open and direct link" between the Praia Grande and the Inner Harbour, "passing by the senate house." It was recommended that this link be wide enough to allow for tree planting.

Another suggestion was to open up a roadway from the Bomparto Fort to Barra, "either skirting the mountain, following the coast all the way, which would have an excellent effect but would be expensive, or springing over it, which would be more picturesque and incur less onerous costs."

In order to comply with the 1864 decree, it was proposed to proceed by expropriating property, which even then was considered to be impracticable... Only in the Chinese districts was it possible to foresee widening the roads to the desired minimum of six meters, given that the buildings there were not very solid, having a life-span of only around fifteen years, after which reconstruction could be undertaken to comply with the new regulations. For that to happen it was important to "determine now the alignment of future roads, which can only be achieved with reliable information after the above-mentioned plan has been established". It was also proposed that the Public Exchequer should expropriate "the necessary land so that any new building will conform to the designated alignment and within a few years the successive reproduction of this system will have put an end to all irregularities in the current roads."

The Commission recognised that, in order to implement these measures, all that was lacking was "great tenacity in execution (...)" This tenacity unfortunately did not exist, since even today "roads" of less than half the recommended width can be found.

2. Removal of faecal matter - sewers, latrines - The commission suggested various solutions for this grave problem which was so important for public health. Since it was neither viable nor recommendable to use sewage in the existing agricultural area, it was thought to be a better solution to channel it into the sea, "constructing for that purpose appropriate conduits, wherever the width of the road allows". However, it was finally concluded that "the matter is not resolved because in most parts of the city and especially in the Chinese district, the narrowness of the roads, their twisting nature, their numerous and varied zigzags at every step would make construction and even the subsequent flow of liquids so difficult that this system of drains does not appear to be viable ". The Commission finally opted for portable cesspits, to be removed every day. Unfortunately we have no way of knowing whether this solution was applied and if so whether it afforded the desired result...

The existing latrines were also sources of infection, so the commission proposed to replace them with new hygienic installations and to create public urinals, both of which were to be "amply provided with water, which is the essential element of all cleanliness".

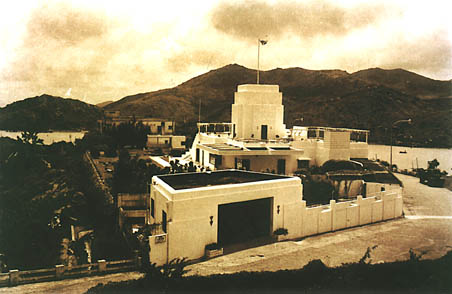

Casa Branca - Convent of the Precious Blood.

Casa Branca - Convent of the Precious Blood.

3. Water supply - Macao was never rich in water, especially drinking water, given that "the numerous wells that supply the population draw upon a vein that is almost at sea-level and made up of seepage water which is always somewhat brackish and full of organic matter and therefore not suitable for drinking". On the hill where the Flora Garden is situated there were three springs with good, though not abundant, water, whence better-off families had the precious liquid brought to their houses. There were also the Fonte do Lilau and the Fonte da Barra, which even at that time were already less salubrious. Patane stream had been an important source of drinking water, sufficient for the needs of not only the settlement of Patane, but also for the boats which came to the Inner Harbour wishing to take on fresh water. In time, however, it became completely polluted by the influx of residual waters from the bordering meadows and was eventually converted into a drainage channel, the San-kiu canal, which was later covered over for health reasons.

Two suggestions were put forward by the Commission: to clean up the existing springs and seek new ones in the hills, or to bring the very abundant waters of Lapa island to Macao, in this case noting that "we do not venture to propose this solution in recognition of the inconvenience arising from the water supply being dependent upon the good or ill wishes of a foreign power."

4. Insalubrious districts- The districts of Horta da Mitra, Volong and S. Paulo, parts of the districts of S. Lázaro, Patane, Sa-cong and San-kiu and many spots in the Bazaar were considered to be insalubrious. The radical solution proposed in order to put an end to all those sources of infection was "the razing of all existing buildings and the determining of new street layouts provided with good subterranean drainage ".

Other proposals consisted of filling in the Sa-cong docks, moving them into deeper water, and covering the San-kiu canal "leaving a covered drain in the centre to carry away overflow from the meadows, forming across the whole width of the canal a broad tree-lined avenue linking the Coelho de Amaral Road to the sea."

5. Markets -The existing markets were small and unhygienic. "The main market, known as the S. Domingos bazaar, is located in a dark and narrow place, where meat, fish and vegetables are piled up chaotically and without the most basic notion of cleanliness "; close to one of its entrances stood " a filthy latrine ". The Commission "believed that three markets would be sufficient for supplying the city, therefore recommended erecting a large central market close to the site where that of S. Domingos now stands, and other smaller ones in the Ponta da Rede square and in Patane, besides the new market still under construction on the landfill between Rua de Miguel Ayres and Rua Bispo Ennes ".

6. Abattoir - The existing abattoir did not have even the minimum conditions for hygiene, so the commission proposed to re-position it next to the sea, close to the D. Maria Ⅱ Fort, and to build "annexed workshops, for refining suet, salting skins, and preparing blood (...)", as well as "stables for observing cattle for forty eight hours (...)"

7. Prison - As the prison did not provide security, hygiene or a rehabilitating social climate, the Commission decided that it should be transferred, suggesting for the purpose a plot "at the heights of S. Paulo, a little behind the ruins of the temple of the same name", where there was "ample land for constructing workshop annexes and gardens which the prisoners would cultivate."

8. Other insalubrious establishments - In this classification were included diverse concerns such as the tannery of Patane, sites for drying fish, bone and feather stores, etc. It was proposed to move them all to the land between the D. Maria Ⅱ Fort and Mong Há, or next to the Barra Fortress.

9. Rubbish collection - The rubbish taken from the buildings and the streets was dumped close to inhabited areas, namely, next to the cemetery, between Flora and the Estrada Coelho de Amaral, or the road to the Portas do Cerco. "There is a simple means to put a stop to these nuisances and it consists of obliging the rubbish collector to convey by boat away from the small peninsula on which the city is located all the litter that his carts can carry."

10. Overcrowding of residences and their internal cleanliness - Some considerations reflect a preoccupation with the well-being of the population, suggesting house visits in order to implement hygienic conditions in people's homes; annual whitewashing, inside and out; prohibitions on the cohabitation of people and animals; and ensuring that the amount of air (in cubic meters) was sufficient for the number of inhabitants in each house.

11. Hygiene in the countryside - Along with the improvement projects to be implemented in the city, the commission also considered the agricultural zone. "The cultivated countryside which occupies the whole basin between the river and the mountain range that traverses Macao from North to South is, as a result of the cirumstances of its cultivation, relatively insalubrious".

In order to overcome this drawback, the commission proposed to "prescribe certain rules to improve the level of hygiene in the countryside", such as renewing the water in the paddy fields, only watering the vegetable plots once a day, replacing the ponds used for irrigation with narrow-mouthed wells operated by hand pumps or windmills.

12. Tree-planting - Being fully conscious of the need to plant trees, the Commission noted some of the benefits of this practice: "the purification of the atmosphere, the draining of excess liquids from land surfaces, the regularisation of meteorological conditions", to which it added "the embellishment of the city and the comfort afforded to the populace during the hours of greatest heat." In order to achieve these ends, they proposed two kinds of tree planting: "Firstly that which should be done within the city itself in the gardens and along the roads, and secondly that which should cover the nearby mountains, causing them to lose their arid and bald appearance."

In that era no one yet spoke of ecology, but by extraordinary intuition the planting of trees and shrubs was promoted, so that, little by little, the peninsula came to have green areas. Guia Hill was planted with trees, and the gardens of Vitória, S. Francisco, Flora, Montanha Russa, Chunambeiro, Gruta de Camões, and Lu-cau (nowadays called Lou Lim Iok) were created. When new roads were opened to the north of Tap-Seac, all the houses had to have a small garden at the front.

From this report we can conclude that the sanitation of the city, which had begun to be implemented during the tenure of Tomás de Sousa Rosa, the author of the order which had originated it, was at last carried out.

EARLY PLANS

The Horta da Mitra district, which had been rebuilt with the same unsanitary conditions after a fire in 1865 had destroyed 200 huts, housed 60,000 people in closely packed houses served by a tight network of alleys. It comprised the area between Rua do Noronha and Rua da Colina, Rua Nova a Guia and Rua Henrique de Macedo, and part of Rua do Campo. It had once been a forest where a group of Chinese emigrants had settled. For quite some time these emigrants lived by selling the firewood they cut there, thus successively increasing the area of the small village. The lack of hygiene transformed it into a source of infection, a problem that only total demolition could resolve. On this site a new district was then built in 1886, later named the Tomás Rosa district. Within its rectangular layout, amidst straight paved roads, it boasted airy houses with good light, a municipal market complying with strict health regulations, and a new temple, the Chong-Kuok-Tou-Tei-Miu (Chinese temple of the Earth God), to replace the demolished "Pagoda of the Household Gods".

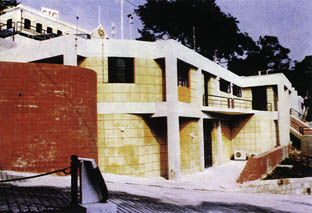

Vista Alegre - Leng Nam School.

Vista Alegre - Leng Nam School.

Governor Horta e Costa took up the initiative again, ably seconded by his director of Public Works, Abreu Nunes. He began his work in 1894, in the district of Tap-Seac, which was bordered to the west by the Rua de Esperança, to the south by part of the Estrada do Cemitério (Cemetery Road), to the north by Rua Adolfo Coelho and the east by the Avenida Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida. In that place there was a meadow lower than the surrounding roads in which the local farmers retained rainwater in improvised dams and used natural fertilisers, thus causing unhealthy conditions. To resolve this problem, after expropriating the property, the area was filled in with earth taken from the Campo da Vitória half way up the hills of Guia and Flora, at the same time creating on the slope an avenue (which has since disappeared) parallel to the present day Estrada da Vitória and the Avenida Sidónio Pais. Once levelled in this way, the meadow was divided into blocks for housing.

The Bairro do Volong (Volong district) was another breeding ground for infection. It was situated in the bamboo grove which in 1622 had obliged the Dutch to deviate from their invasion route, for fear of ambush, and attempt to scale Guia Hill. This hesitation led to their defeat and earned the spot the name of "Campo dos Arrependidos" (Field of the Rueful). It was later acquired by Francisco Volong, a naturalised Portuguese of Chinese birth and became known as the "Horta do Volong", or Volong's Vegetable Garden, degenerating over time into an insalubrious and crowded district. Following an epidemic of the plaque of which it was the epicentre, it was expropriated in 1895 and completely demolished. Two years later, furnished with rectilinear roads in a rectangular grid, a drainage system, and even foundations for the houses to be privately erected there, it was handed over to the Leal Senado. The extensive "Horta do Volong" was located, for all intents and purposes, in the place of the present district, between the Estrada do Cemitério to the north, Rua de S. Lázaro (probably the present day Rua Nova de S. Lázaro) to the west, Rua Ferreira do Amaral to the south and, to the east, the Avenida da Flora, (which no longer exists) possibly even stretching beyond the present Estrada da Vitória. It was, however, partially swallowed up by the S. Lázaro district.

This district developed around the Nossa Senhora da Esperança Church and the S. Lázaro Hospital which had been built to treat lepers. It mainly consisted of humble cabins, with only a few nicer houses along the road leading up to the church. Since most people were reluctant to live in the area for fear of disease, only the most miserable did so, joined shortly afterwards by a few Chinese Christian converts. The S. José chapel was founded for these converts so that they did not have to attend the church of the lepers, until, in 1663, the main church was opened to all. The sanitary conditions in the area were dreadful, and the plague of 1895 found there a fertile ground in which to spread. For this reason, by an order of 30 June 1900, Governor Rodrigues Galhardo ordered the district to be completely demolished, including the aforementioned chapel. Only the church dedicated to Nossa Senhora da Esperança (Our Lady of Hope), which was completely rebuilt in 1885 by order of Governor Tomás Rosa, was saved.

THE COAST LINE

The progressive siltation of the Macao coastlines provoked two reactions: on the one hand, the exploitation and consolidation of the reclaimed land to the east and west of the peninsula for future urban planning, and on the other hand, the promotion of studies on the creation of new ports where deep draft ships could berth. In 1869 land reclamation work began next to Chunambeiro which would make possible the cleaning and organisation of the area, at a spot where the road from the city centre terminated. In 1873, this road was extended to the Bomparto Fortress, as a result of further land reclamation, thus becoming a continuation of the beautiful tree-lined avenue along the frontage of the Praia Grande, along which the best buildings of the period were constructed -homes, small palaces, and public service buildings.

Meanwhile, on the Inner Harbour side, the land reclamation near Barra, which was begun in 1868, improved access to the area of the A Ma Temple, by way of a harbour road linking it to Patane, subsequent to the occupation of the old bays of Praia do Manduco and Praia Pequena. In 1873 the governor, the Visconde de S. Januário, ordered the land-fill to be extended along the Inner Harbour to the Barra Fortress, and drainage facilities to be installed along the roads next to the Bazaar. These works were concluded in 1881. The Patane dock was completed in 1887.

In 1884 a project for the port of Macao was drawn up by Adolfo Loureiro. Essentially, it aimed to regulate sea currents by means of various works along the coast, to build wharves and link Ilha Verde to the peninsula by land reclamation, creating a dyke and filling in the river. A new district was to be constructed on this isthmus with a large avenue and transverse roads forming several housing blocks. It was not until quite some time later that the principles governing this plan were realised, at least in part.

The construction of the Ilha Verde isthmus was ordered by a decree of 1890 during the governorship of Councillor Borja, with several aims:

- To increase the main flow of the river current by eliminating a secondary channel, so that the tidal system would help to keep the other channels open.

- To promote the cleanup of the seafront where all kinds of detritus had accumulated.

- To link the peninsula to the small island whose ownership was contested by the Chinese authorities of the time.

These works continued into the early years of the 20th century when a general city improvement plan was implemented, which included installing water and drainage systems.

Admiral Hugo Carvalho de Lacerda Castelo Branco, a hydrographer who worked in Macao between 1918 and 1927 as director of Harbour works and as interim governor, wrote a report listing the results of work carried out at that time as well as projects which were never actually realised. Besides social, economic, political and cultural questions which do not concern us here, he refers to the idea of a reservoir on Taipa to hold rain and spring water, exactly like the one which now exists, as well as others in Guia and Coloane which were never built.

He also refers to various attempts throughout the years to improve Macao's harbours, with a series of successes and interruptions, drawing particular attention to the artificial harbour of Rada which was planned and built between Praia Grande and Macao-Seac and which had two sea walls to the east and the south. However, the general plan was more ambitious. The proposal was to build a large artificial island between Macao and Taipa, Rada Island, which would include a system of canals, docks, defensive dykes, etc. The access channel to the harbour required frequent dredging to keep it clear, and it was the dredgings that would provide the material to build the island, which in turn would contribute to a better regulation of the river current by channelling it and protecting the dredged areas, thereby preventing further siltation. However, this plan, like so many others, was not put into effect, and we do not know why.

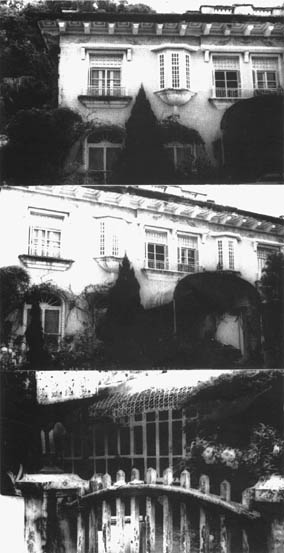

The verandas of traditional buildings (the old headquarters of the Clube Argonauta). Photograph by Joaquim de Castro.

The verandas of traditional buildings (the old headquarters of the Clube Argonauta). Photograph by Joaquim de Castro.

A new, detailed study was made in 1929, based on different premises and therefore presenting a different solution.

PLOT PLANS

Various plot plans were put forward, namely for the coastal areas, and, from 1900 onwards, for the districts of Avenida Horta e Costa and Avenida Ferreira do Amaral, including street plans which would come to be important transportation routes. The S. Lázaro district was completed, and the public housing districts of Tamagnini Barbosa and Hipodromo were built. More landfills along the Praia Grande and in the Outer Harbour provided yet more land for construction. By the middle of this century the city had doubled in area since the end of the last.

MASTER PLANS

However, there was no master plan linking the various zones; the first such plan only appeared in the 1960's, drawn up by Garizo do Carmo. Its main goals were the preservation of the older districts, the exploitation of free spaces, and the definition of an industrial area between Areia Preta and the Outer Harbour, for which an adequate road system was recommended. The plan maintained the areas traditionally used for harbour-related activities, trade, warehousing and lower income housing. It proposed using the new land at Praia Grande and the Outer Harbour for luxury commerce, hotels and more important services.

Thus began the presentation of a series of urban plans that has continued until the present day. In the 1970's various plans proposing different solutions to Macao's urban problems were drawn up.

In 1976, architect Tomás Taveira drew up a plan recommending urban renewal, with new development areas on the islands, in order to solve the problem of congestion in the old nucleus. It set out new industrial areas and proposed new low-cost housing districts.

Meanwhile, the Overseas Development Administration had begun work on a "Territorial Map of Macao." This was initiated in 1970 and concluded in 1978, not by the Directorate of Public Works of the Ministry which had originated it, but by the body which replaced it, the Ministry of Inter-Territorial Cooperation. When it was finally presented in 1979, this plan was found to be already out of date, where upon the Government of Macao asked Profabril, a private company, to revise it, in order to have available a physical map of the territory to guide their decisions on urban development.

This "General Development Plan for Macao" was intended as a starting point for urban development based on future specifications for which it would supply the general parameters. The plan recommended massive land reclamation schemes, first on the peninsula and, in the long term, on the islands too. It focused on socio-economic programmes, the protection of cultural heritage, the planning of green spaces and the urban fabric, and a general transportation policy. All of this was subject to the availability of technical and financial resources and to the legislation which would have to be implemented. One of the essential elements of this plan was the intention to create a completely new city in the areas reclaimed from the sea on the east coast of the peninsula.

In the same year, the architect José Catita drew up another "General Development Plan", highlighting the priorities for intervention in the road network and proposing a group of urgent measures. These included the implementation of plot or housing estate plans, the revision of existing plans, the study of infrastructure, and the construction of the Flora Tunnel and the related road links and landscaping. Several phases of land reclamation were also mentioned, in anticipation of the airport and the new sea port. Land use complied with given percentages, and occupancy levels were set for residential areas.

In 1984 a Stuttgart company, with the help of architect Castelo Branco, proposed drawing up a "Master Plan for the Territory of Macao". Included in their objectives was the creation of incentives for private development, the co-ordination of government resources for land use and infrastructure development, the improvement in quality of life and working conditions, the preservation of Macao's historical, cultural and natural features, the determination of the best sites for housing, industry and services, the revision and integration of existing plans to ensure their continuity and, finally, the promotion of this development process among both private and public sectors. From among the various elements of the plan, the following stand out: territorial land use and hierarchies for its use, the transportation network, infrastructure, green spaces, and, obviously, the areas destined for construction.

In 1986-87, the firm Asia Consult drew up a new master plan to include the islands, with the collaboration of the architect Luís Rebolo. This plan was immediately subject to revision. It aimed to define the general precepts for building density and transportation, and methods of implementation. It was concerned with providing enough land to meet foreseeable housing needs, creating premises for various economic activities and social facilities, curbing excessive growth on already developed land, protecting and exploiting green spaces, improving links to the outside (airport, harbour) and internal transportation (street maps and the new Macao-Taipa bridge), reviewing the infrastructure (water, drains, rubbish collection, electricity), and rationalising urban management. The plan anticipated intensive occupation of the peninsula which would exhaust the available capacity; the progressive launching of new land reclamation projects; the control of urban sprawl; and the safeguarding of the most important landscape and heritage features. In Taipa, it was concerned with the development of the Baixa da Taipa, and the preservation of the principal natural areas and the coastline; in Coloane, it was concerned with the preservation of the island as a natural zone and the maintenance of the coastline. A point deserving special mention in this report was the planning of land reclamation, which was analysed from the perspective of its impact on the landscape and the hydrographic environment, as well as its adequacy for projected use.

Steps leading to the old Santo Agostinho Convent. George Chinnery, 1829. Col. Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa.

Steps leading to the old Santo Agostinho Convent. George Chinnery, 1829. Col. Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa.

BLOCK PLANS

All these general plans, drawn up over three decades by diverse authors, obviously present different ways of approaching the subject, and it is not easy to render them compatible. In spite of this, they have provided the basis for various specifications which have regulated construction on the peninsula and the islands.

In 1987, a regulation was made for the use of the site of the old Liceu Infante D. Henrique, dividing it into four sections, one of which was destined for public recreational purposes. The alignments, volume measurements and purposes of the finished buildings were defined. Outline designs showed the siting and height of the different blocks, establishing the respective maximum, minimum and fixed values. The completed project differed somewhat from this regulation, given that it included the highest building in Macao: The Bank of China, with its 42 stories.

THE PRAIA GRANDE/ZAPE

One common feature of these disparate general plans was, as has been mentioned, the recognition of the need to carry out more land reclamation and exploit the new areas thus created.

When it became clear that there was insufficient land on the peninsula for the desired expansion, this reclamation became a reality and was used in different ways. Part of the Praia Grande Bay was filled in with compacted soil and divided into blocks by wide roads. In the space between the city and the strip of sea separating the peninsula from the island of Taipa, two large landfills were created, called by their initials: ZAPE - Zona de Aterros do Porto Exterior (Outer Harbour Reclamation Zone) and NAPE - Novos Aterros do Porto Exterior (Outer Harbour New Reclamation Zone), this latter still being under construction.

The first Urban Development Plan for the Outer Harbour and Praia Grande was made in 1964 by the architect Leopoldo de Almeida. Although this plan is essentially for the Outer Harbour reclamation zone, the proximity of the two zones led to the reorganisation of part of the Praia Grande in order to solve the traffic problems and, simultaneously, to create tree-planted open spaces.

The programme recommended a separation/ link between the new area and the existing city. This aim was achieved, on the one hand, by opening up Avenida Rodrigo Rodrigues from the coast, by the Hotel Lisboa, to the Reservoir in the extreme N. E. On the other hand, two links with the city centre were designed: one passing through the valley between the S. Januário and Guia hills (forming an extension of the Calçada do Gaio/ Calçada do Paiol) and another carved out half way up Guia Hill (Estrada de Cacilhas) making it possible to reach Areia Preta without going around the reservoir. Almost all of the area under study was intended for residential purposes, with provisions for green areas and sporting facilities also. In addition, the possibility of building a Marine and Air Terminal in the extreme eastern part was considered.

Given that the plan was not put into immediate effect, it was soon considered outdated, and so another study was done in 1979 by the Prescott Group, with the architect Lima Soares as the consultant in charge.

This plan was concerned with adapting development to local climatic conditions, paying special attention to the north-south direction, between the sea and the hills, which boasted excellent ventilation and panoramic vistas. The non-built-up areas were destined for public use, with an emphasis on pedestrian circulation - various green areas were projected, which would later be equipped with leisure and sporting facilities. The buildings would be between 15 and 19 stories tall, but not exceeding 60 meters in height, in order to preserve the presence of Guia Hill. As a general rule, it was obligatory to build a colonnade, thereby forming an arcade.

The road system was based on two parallel routes, the Avenida Dr. Rodrigo Rodrigues and the Avenida da Amizade, which would be crossed/ joined by secondary roads. The proposal also included an access ramp to the Estrada de Cacilhas on the bank of the Reservoir, a passage under the Estrada dos Parses with a small embankment linked by a tunnel to the Calçada do Gaio, and, no less important, the opening of a tunnel through Guia Hill.

Another essential factor was the S. Francisco junction, next to the Hotel Lisboa, which was the subject of a special study submitted two years later: the Block Plan for the Transition Area, with detailed solutions for the various existing architectural elements.

The same company then went on to develop a new study for the area under the guidance of the architect Eduardo Flores. This plan was presented in 1985 and subject to a series of compromises, in light of the existing infrastructure. This plan maintains the principle of preserving Guia Hill, proposing a height clearance of 60 meters, except in designated areas where the clearance is raised to 90 meters.

This plan proposes to regulate building density and determine the standards for urban construction and exterior finishings, superseding the regulations in force. Its rules are specific for each block and are relatively detailed. The link between Calçada do Gaio and an embankment and tunnel under Estrada dos Parses is maintained, as is the extension of Avenida Dr. Rodrigo Rodrigues to the south, though both are adapted to conform to the Urban Intervention Plan for Guia and S. Francisco hills. An area is reserved for access to the projected tunnel through Guia Hill. The hill slopes are treated as total nature reserves, and there are also areas of partial reserve, where use is restricted to public and recreational facilities.

The plan specifies pavement types, urban landscaping, tree planting etc., with the aim of creating a pleasant environment. A system is established whereby buildings must be set back from the roadside, giving rise to pedestrian corridors along the dividing lines of the blocks. Arcades are also obligatory wherever there are upper floors stipulated in the plan.

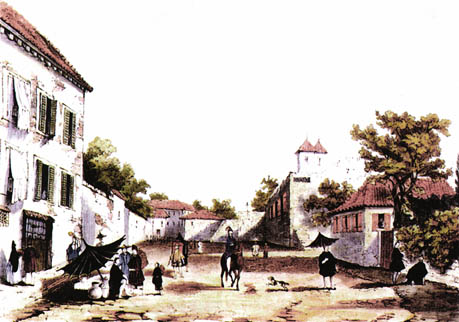

Street scene with contemporary architecture. George Chinnery, 1830 approx. Col. Toyo Bunko.

Street scene with contemporary architecture. George Chinnery, 1830 approx. Col. Toyo Bunko.

NAPE

As a logical continuation of this area, a New Outer Harbour Reclamation Zone arose to the south and came to be known by its initials NAPE (Nova Zona de Aterros do Porto Exterior). This development plan was drawn up, starting in 1982, by the Palmer and Turner Office of Architecture and Planning under the responsibility of architects Siza Vieira and Fernando Távora.

The point of departure for this plan was the importance of the site, which was intended to constitute a pleasant "entrance hall" for those arriving in the territory by sea. It would project like a primordial element from the urban landscape around it, outlined against the background of the distant Lapa mountains.

The study concentrated on two distinct areas. The first phase was to the south-south-east of the ZAPE nucleus and separated from it by a canal running along the northernmost avenue of the zone. Access would be via a bridge over the canal, extending the central tree-lined walkway of ZAPE, which held an axial position here, inter-linking all the internal roadways, to the new coast line. The second phase was at the north-north-east extremity of, and accessed by, the northernmost avenue, with a second link to the peninsula via an isthmus to the north of the Reservoir on which low cost housing would be built. This landfill area was destined for industrial purposes and a polytechnic school surrounded by green areas.

The "Master Plan for the Macao Territory" previously referred to caused significant alterations to the NAPE plan, namely the reduction of the landfill area, which led to modifications of a general nature. The second phase lost its importance and was reduced to some supporting facilities for the maritime Passenger Terminal and boxes for the Grand Prix. The first phase, now called "Zone M", was the main object of the revision carried out in 1987, which implemented changes due to the new reduced area and projected use. This revision sought to adapt the proposals of the original plan to the new general framework for development of the territory, bearing in mind its interaction with adjacent areas and proposing a coherent relationship between the various features that would form this urban expansion zone. The ZAPE plan to the north affected this study to some extent, influencing building height and stipulating the road link points.

A new intermediary solution was proposed, which maintained the general concept of the earlier plan while adapting it to the new set of requirements. A minimum area of 35 hectares was stipulated, which would permit a scale corresponding to the importance of the site and the implementation of coherent urban planning. The length of the canal between the landfill and the existing coast was increased, anticipating future use of this space for recreational activities, and the preservation of water quality was to be ensured by creating a system of automatic tide valves at both ends of the canal.

The road structure maintains the former north-south and east-west grid, with the last avenue to the south being eliminated and replaced by a pedestrian area. In the east-west direction, two routes have a lower profile, alternating with three avenues parallel to the coast line. The perpendicular roads all have the character of avenues, but their profiles are altered by the positioning of the tree borders. The landfill is accessed via two roads running in opposite directions, on either side of a central shaded walk reserved for landscaped spaces, in extension of the tree-lined walk anticipated in ZAPE. The whole automobile road network is based on this entry/exit. Pedestrians also have the use of two viaducts spanning the canal at its eastern and western ends over the sea walls, which will connect with the pedestrian area to the south via two coastal walkways along the edges of the landfill.

The new area is essentially designed for residential buildings, with space for commerce, equipment and parking on the first two floors. These will form a continuous frontage along the roads, above which will rise the apartments, up to a maximum height of 30 meters and occupying around 80 per cent of each block. However, other uses are also anticipated: a hotel may be sited on the south-south-east perimeter; an area to the east will be reserved for future school and/or sporting facilities; and a medical clinic will be built next to the square to the east. Until these projects are realised, the sites reserved for them will be used as green zones.

This enumeration of planning studies is not exhaustive. I believe that there are others which have not been cited here due to the difficulty of locating them.

However, revisions are constantly being made to the existing plans, motivated by problems arising from their implementation as well as by new partial plans for the areas not yet covered in the specifications.

And the city does not stop growing!

ARCHITECTURE

ANTECEDENTS

In order to understand the layout of early Macao and the anatomy of its buildings, we must focus first on the traditional form of Chinese houses.

Nowadays, when we come across ancient buildings isolated in the traditionally Chinese districts, it is certain that they are remainders of old courtyard quadrangles, the most widespread system in all China, with minor variations. According to this system, four buildings are distributed one on each side of a square space, leaving a central courtyard onto which all of the rooms open. Even today, vestiges of this custom can be found, in contemporary buildings, in which the doors to the various divisions of the house open directly onto the living room, which stands in for the old central courtyard.

Generally speaking, the building to the north with its southern façade overlooking the courtyard was called the major house because it had the best position (warmer in winter and cooler in summer). This was reserved for the head of the family or the members of the older generation. Other family members were spread out in the side buildings, and the building at the opposite end was used for children and servants. The entrance to this compound was usually in the south-eastern corner under a covered area, which was limited by the end wall of the side building and formed a porch with a second doorway into the courtyard.

The quadrangle courtyard takes on distinct characteristics in different regions of China, due to the diversity in climate, building materials and customs. In the north, where the climate is dry and cold in winter and cool in summer and where there is plenty of space and relatively few people, the courtyards are quite large. In winter, more light is able to enter the buildings. The four sides are not directly linked with each other. But in the hot and humid south, where there is a large concentration of people with consequently less space allocated to them, the courtyards could not be very large. The buildings on the four sides were linked into one unit around a small courtyard which provided light and sun, ventilation and inter-connection between them. At times, the structures on the four sides had two storeys, which helped to make the courtyard seem even smaller. This type of house was sometimes referred to as carimbo (rubber stamp) because of its shape.

Praia Grande seen from the S. Pedro Fort. George Chinnery, 1834 approx. Col. HKMA.

Praia Grande seen from the S. Pedro Fort. George Chinnery, 1834 approx. Col. HKMA.

The dimensions of these compounds varied according to the owner's economic status. In some cases, new north-south facing compounds were added, forming additional courtyards. More rarely, if space was an issue, this extension could be added in an east-west direction, but in either case, the most important apartments were always the axis of the compound. This organisation was appropriate for the old Chinese Confucian ethic, separating as it did the old and young, masters and servants, and emphasising hierarchical relationships of "higher" and "lower."

EARLY SETTLEMENT IN THE PENINSULA

When the Portuguese arrived in Macao they found two temples, one in Barra and the other in Mong Há, each surrounded by its own village.

The Barra temple, Ma Kok Miu, had been built at the start of the Ming dynasty and altered during the reign of Wan Li, who governed China between 1573 and 1621. The system of courtyard construction has been adulterated here because of the constraints imposed by the terrain. The courtyards follow on from each other on different levels, climbing the mountainside. The entrance level, protected by a granite wall subdivided into sculptured panels and reached via a short flight of steps guarded by stone lions, has a double portico dedicated to Sin Fong, "he who knows everything at first hand;" to the right is the main temple in which the goddess Neong-Ma is worshipped, with a circular side entrance carved from a single piece of granite. Behind is the turret of the crematorium for offerings, in the form of a pagoda. Between these temples are two large rocks engraved with images of the ship that carried the damsel of Fukien, who, according to legend, metamorphosed into the goddess as she climbed the slope. Granite steps lead to the second courtyard where the temple to Tin Hau, Queen of the Sky, is situated. Another flight of steps leads through rocks and pagoda trees to the third courtyard, where we find a temple to Kun Yam, the Goddess of Universal Benevolence, which was built during the Qing dynasty.

The Mong Há Temple, dedicated to Kun Yam, was built into the hillside, which limited its growth. It therefore has only one courtyard with the chapel of the goddess, and, to the left, a pavilion dedicated to Seng Wong. It is not known when this temple was founded, only that additions were made in the 17th century.

The first Portuguese settlers in Macao established themselves on the west coast, beside the Inner Harbour, close to the A-Ma temple. Although their initial situation was precarious, after their victory over the pirates and the subsequent permission from the Chinese Emperor for them to inhabit the peninsula, they began work on a new settlement, a little further north.

Since the propagation of the Christian faith was one of the motivations for the Voyages of Discovery, representatives of various religious orders always accompanied the expeditions, leaving traces of their passage in their wake. As in other places, in Macao they built churches and convents, schools and hospitals.

The first Christian house of worship to be built on the peninsula was the S. António Chapel, between 1558 and 1560. At that time Macao belonged to the diocese of Malacca, created on 4-2-1558 by the Pro Excellenti Praeeminentia Bull of Pope Paul IV. It was roughly built of wood and was victim to several fires, in 1608, 1809 and 1874, being re-built each time. The current building, in neo-classical style, dates from 1875, with the façade and tower having been renovated in 1930, as a granite plaque on the front announces.

At the same time the S. Lourenço Church was built. It was re-built in lath and plaster in 1618, and repaired between 1801 and 1803. Between 1844 and 1846 it was totally remodelled according to the taste of the period by the Macanese architect José Tomás d'Aquino. Its European characteristics made it different from the other churches in the city, especially in the width of its single nave, only broken by the existence of two small side chapels, thus forming a reduced Latin cross. Further renovations were carried out in 1897-1898 and in 1954.

The third Christian house of worship to be built was a small wooden chapel dedicated to the Nativity of Our Lady, which was elevated to the status of cathedral in 1576, after the creation of the diocese of Macao by Pope Gregory ⅩⅢ's Bull Super Specula Militantis Ecclesiae, of 23-1-1575. The cathedral was replaced by a lath and plaster construction in 1622 or 1623, and newly rebuilt in1844 by Tomás d'Aquino, on the same site but with a different orientation. The new façade faced north, since the old west-facing façade had partially obscured the Episcopal Palace. After the earthquake of 1874, major works had to be carried out, namely on the towers and the roof, but without altering the layout.

The first Jesuit house, created in 1565, was in one of the casinhas térreas (low houses) made of straw, next to Santo Antonio's chapel. It was there that Bishop D. Melchior Carneiro stayed temporarily when he arrived in Macao in 1585, until his own residence could be built. It caught fire in 1596 and was rebuilt and enlarged in 1597 on the site adjacent to the S. Paulo Church.

Bishop D. Melchior Nunes Carneiro Leitão, S. J., bishop of Nicaea, Patriarch of Ethiopia, was not the bishop of Macao, but "Governor of the bishopric", as bishop of China, Japan, Korea and adjacent islands. He was the main instigator of urban improvements in his time, founding, in the same year that he arrived, the Confraria da Misericórdia (a charitable institution), the S. Rafael hospital and the S. Lázaro hospital.

The Confraria da Misericórdia became the Santa Casa da Misericórdia, which has always given aid to the poorest of the poor. The initial building included a church, consecrated to the Visitation of Our Lady, which was demolished in 1883 because of its ruined state. At the beginning of the 19th century, a false façade was added to the building, in the neo-classical taste of the time.

The S. Rafael Hospital was created to serve Christians and pagans, rich and poor. The Senate doctor was the first to be responsible for hospital services and its pharmacy, where the first vaccines in this part of Asia were administered. After various repairs and alterations of use, the hospital building was recently adapted for use by the Monetary and Foreign Exchange Authority of Macao.

The S. Lázaro Hospital was intended for the treatment of lepers, and the Nossa Senhora [Our Lady of Hope] Chapel, normally known as S. Lázaro, was built next to it. The hospital was demolished along with the district in 1900. The present church was re-built in 1885 on the site of the earlier church, of which only the transept, dating from 1637, remains.

In 1572, an elementary school opened next to the Jesuit residency, from which the S. Paulo college later developed, and this was elevated to the status of University in 1594. As their first church, which was still built of straw, had burned down, the Jesuits constructed another in wood with a tiled roof. This too was replaced, in 1573, by a lath and plaster construction, dedicated to the Mother of God, with the Jesuit governor D. António Vilhena personally paying for the cost of tiling the roof.

In 1580, on the hill behind the residency, Father Miguel Ruggieri founded a house with cells for Chinese catechumens, in a corner of the college site. It had a chapel dedicated to S. Martinho de Tours, and stood on the site where the "ruins of S. Paulo" now stand.

View from Praia Grande towards the Bom Parto Fort. George Chinnery.

Pencil and ink on paper. 1833-36 approx. Col. HKMA.

View from Praia Grande towards the Bom Parto Fort. George Chinnery.

Pencil and ink on paper. 1833-36 approx. Col. HKMA.

When the Madre de Deus Church again caught fire, it was abandoned by the Jesuits, who resolved to move it to the site of the aforementioned chapel in 1586. There was another fire and another reconstruction, with lath and plaster walls and a tiled roof. The re-built church, again dedicated to the Mother of God, was inaugurated on Christmas Eve 1603, with great pomp and solemnity. But the misfortunes had not ended: after the expulsion of the Jesuits from the territory, troops were billeted in the College, and, in 1835, a fire which started in the kitchens completely destroyed the college and the church, with the sole exception of the façade we know today.

In 1547 the Portas do Cerco was built, with barracks for Chinese guards above it. This structure collapsed and was rebuilt in 1674, and the barracks moved into an annex. The current Portas do Cerco is integrated into the Macao-China frontier.

In the Patane area there was a fort called Patane or Palanchica. No one knows exactly when this fort was built, although 1625 is the popularly accepted date. It formed part of the city wall linking the Inner Harbour to the Monte fort, and its purpose was to protect the city from a possible Chinese invasion. It was made up of three platforms, each with a piece of artillery, as can be seen from drawings of the time. It was demolished around 1640, along with all the stretch of wall to which it was joined.

Throughout the last decades of the 16th century, the Portuguese were building their houses and marrying the locals. According to documents of the time, in 1578 there were ten thousand inhabitants and five churches, with around two hundred Portuguese houses.

In 1579, the Spanish Capuchin priests founded the Nossa Senhora dos Anjos Convent, later known as the S. Francisco Convent. It was built on a spit of land surrounded by water on three sides, in the extreme northern part of the Praia Grande Bay. It had a spring with good water and enjoyed, naturally, a beautiful view. On the small overhang to the north, the Nossa Senhora do Rosário Chapel was built, on the site now occupied by the S. Januário hospital. For some time, a small seminary existed there. A convent of Clarissas (nuns), who had come from Manila and had their own private church, existed here as an annex from 1633 until the end of the 19th century.

The Leal Senado, founded in 1583 when Macao was elevated to the status of a city, would originally have been installed in a single storey building, later substituted by the present building, as we will discuss later.

In 1586, the Spanish Augustin friars bought a casinha (little house) in order to found what would become the Nossa Senhora da Graça Convent. As occurred with the Franciscans, the Spanish priests were replaced by Portuguese in 1589, and in 1591 the convent was moved to the heights of the city, close to the present Largo de Santo Agostinho where the Nossa Senhora da Graça Church was also built.

The Dominicans arrived on the peninsula in 1587. The provisor of the bishopric allotted them some wooden houses, where they founded the Casa de Santa Maria do Rosário de Macao, with a chapel of the same invocation, also built of wood. When the Portuguese Dominicans took charge of these premises, they created a hospital there for religious orders passing through Macao, and also a school for instruction in reading, writing and Latin, and later a course in art. In 1590 they built the S. Domingos Church, in a mixture of western and local styles, which was suitable to the climate the building materials available then. The convent was re-built in 1721, at the initiative of its vicar, brother José da Cruz.

In 1592, the Lin Fong Miu, or Lotus Temple, was built at the foot of Mong Há hill, beside the present Estrada do Arco. This became the place where high-ranking mandarins stayed when they visited Macao. The traditional architectural form has been largely used here, with courtyards following each other in both directions.

In 1594, the Senate and the people pooled resources for the re-construction of the São Paulo college, which was the first University in Macao, and even in the whole Far East. On the 1st of December of that year, the program of General Studies of the Madre de Deus College was created, with faculties of Letters, Philosophy, Moral Studies, Canonical Law and Theology, which conferred degrees of Master of Arts to the laity and of Philosophy and Theology to those in holy orders. Functioning as annexes to the University were the Seminário Nipónico de Santo Inácio, founded in 1623; a seminary for the children of Portuguese settlers; and the Procuratorship of Japan. This boasted a large library containing thousands of books and a wood block printing press as early as 1585; another printing press, with moveable type, was installed in 1588. The city coffers were also moved here, since it was considered to be the safest place on the peninsula.

On Ilha Verde, known at the time as ilha dos diabos (Devils' Island), the Jesuits built, in 1603, a thatched house and chapel, which under went various alterations throughout the years, as they were demolished and re-built according to the tastes and wishes of the authorities at different times. In 1617 some two-storey houses and two chapels -dedicated to Nossa Senhora de Santiago - were authorised. These were pulled down by order of the Senate in 1621 and later re-built.

In 1625 a Casa de Fundição (foundry) was established in Macao. It was managed by two Spaniards; Manuel Dias Bocarro, who would later become a founder of great renown, trained there, moving on to manage the foundry in the Largo de Chunambeiro the following year. It produced artillery parts and bronze bells for the Portuguese fortresses in the East and even for Portugal.

Street scene. Macao. George Chinnery. 1837 approx. Col. Toyo Bunko.

Street scene. Macao. George Chinnery. 1837 approx. Col. Toyo Bunko.

The present Kun Yam Tong temple was built in 1627, close to the old Kun Yam Ku Miu. Since the reign of Wan Li, who ruled China from 1573 to 1620, there had been a Buddhist Temple there (P'ou Tchai Sim Un), successively enlarged with new pavilions, built on three ascending levels. Behind the third temple is the cemetery for monks belonging to an esoteric sect. The temple was built of grey brick, with a granite staircase and balustrade. It is decorated profusely inside with multi-coloured glazed earthenware reliefs representing religious scenes, covering the upper part of the walls under the eaves of the green glazed roof and in friezes along the ridge-pieces.

According to an account of the time, written by the Macanese friar Paulo da Trindade, Macao was, in 1630, the second largest Portuguese city in the East (after Goa), with "large and sumptuous buildings and large houses with wide courtyards and gardens".

In 1633 the Santa Clara Convent was founded by Spanish Clarissas. Today, only part of the convent wall remains, next to the Santa Rosa de Lima college. In the same year, the Jesuit Visitor, Father André Palmeiro, ordered the construction of Nossa Senhora do Amparo Church. It was created as a catechumenate for the Chinese, not far from the São Paulo college, outside the city walls. The São José Seminary was founded by the Jesuits in 1728, in the Rua do Mato Mofino, close to the São Lourenço Church.

FORTIFICATION

If the 16th century was one for building the first churches, the 17th century can be considered as the period of fortresses, some of them linked to the new churches (while some of the already existing churches were re-built: São Paulo in 1602, Santo António in 1608, São Lourenço in 1618, the Cathedral in 1623).

The oldest defence installation must have been the above-mentioned Patane (or Palanchica) Fort, close to the Santo António Chapel.

The majority of the fortifications were constructed from 1622 onwards, sometimes in places where there already existed ramparts, which had formed a first line of defence. At that time, the city was surrounded by a wall of lath and plaster, which began in Patane where there was an arched gate called the Porta do Santo António or the Porta de São Paulo. The wall followed the coastline of the Inner Harbour to the west, then headed for Monte Hill to the São Paulo Fortress adjoining its north-west bastion. From the south-east bastion of the same fortress, the wall descended to the São João Bulwark, next to which was the Porta do Campo or Porta do São Lázaro. It then turned towards the São Jerónimo Fort and ended at the São Francisco Fortress, at the northern end of the Praia Grande Bay.

Another stretch of wall, to the south of the peninsula, started at the Bomparto Fortress, following the west slope of Penha hill to the Nossa Senhora da Penha de França Fort. Continuing on down the eastern slope, it terminated next to the Inner Harbour.

With the experience gained in their other stops around the world, the Portuguese applied the most modern construction techniques to the fortresses they erected in Macao: walls not more than five meters high, following the contours of the land, with a depth of three or four meters terminating in steps, platforms, bastions, casemates, and bulwarks for exterior defence. The walls were made of lath and plaster, with brick parapets; their builders, Portuguese military engineers, knew how to adapt their previous knowledge to the local materials and building methods.

The Nossa Senhora do Bomparto Fortress was already completed in 1622, although the date of its construction is not known for sure. Previously there had been an Augustinian hermitage on the site. The walls, of lath and plaster and stone, were built on the existing rocks at their base and supported by granite foundations which rose to an average of 1.2 meters above the rocks. Built to provide covering fire for the Outer Harbour, it also protected the access to the Inner Harbour, defending the transition area between them both. Originally it was in the form of an irregular quadrilateral, changing later as it was extended. It had an arsenal and lodging for the garrison. The parapets had eight openings for cannon, and from them ran the wall linking this fort to that of Penha, on the top of the hill to the west.

Another of the oldest forts, which was demolished, re-built and then demolished again, was that of Nossa Senhora da Penha de França. Within its walls was a chapel dedicated to Our Lady, opened on 29 April 1622. Although it was located on the top of Penha Hill, it was considered to be a coastal fortification, with the main objective of repelling sea attacks. Its firepower covered the greater part of the peninsula, since the six cannon on its platform could fire in arcs over the city.