19 Other genres are lagu stambul (stambul theatre songs), lagu bangsawan (bangsawan theatre songs), lagu mendu (mendu theatre songs of Riau and Pontianak), lagu Dul Muluk (Dul Muluk theatre music of Jambi and Palambang) and lagu mamanda (mamanda theatre songs from south Kalimantan). In addition there is lagu orkes gamat (music played on a Malay string and percussion ensemble for couples dancing in west Sumatra and Bengkulu) and lagu asli paisisir Melayu ("[...] authentic coastal Malay music [...]", which is found in many coastal areas of Sumatra, Malaysia and elsewhere). Not only in western Indonesia but in the east too, as in Ambon and Irian Jaya (especially the Biak and Serui areas), folk songs with harmonic accompaniment of reputedly Portuguese origin are sung with a band consisting of plucked strings, including ukeleles, guitars and large plucked bass, together with a local tifa (drum).

These syncretic musical forms accompany a large range of dances, mostly performed by groups of couples, who sing improvised pantun verses in response to each other. In Sumatra and Malasia these dances include the tari saputangan (lit.: handerchief dance), tari payung (lit.: umbrella dance), tari lilin (lit.: candle dance), tari joget or tari ronggeng (social couples dancing with lincah (hopping and other foor movements)), and tari dondang sayang (lit.: love-song dance), lagu dua (lit.: two song; danced in fast triple metre or alternating metres) and sad sinandung dances.

We shall now look more closely at one of the above-mentioned genres: lagu-kapri, performed on the west coast of North Sumatra. This Portuguese influenced Malay music accompanies the rituals performed in the life crisis ceremonies.

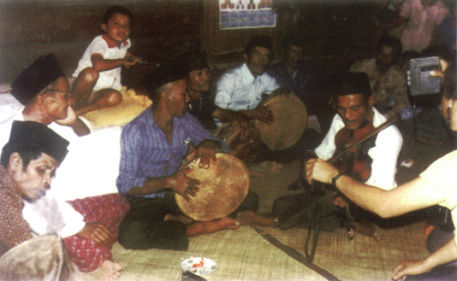

Biola (violin) and gandang (frame drum) players,

part of a kapri-style ensemble, in Bottot, near Barus, in north Sumatra.

Photograph taken in 1981, by Hidris Kartomi.

§2. KAPRI -STYLE MUSIC

Kapri -style music is performed by an ensemble comprising a vocalist, a 'biola' (violin) player and two or more 'gandang' (frame drum) players. It usually accompanies such dances as tari saputangan. Its song texts, musical style and context of performance are similar in some respects to dondang sayang and other harmonised Malay songs found throughout the Malay-speaking world. Yet it has its own unique pasisir (coastal) Malay identity, based on the fact that it incorporates elements of the local pre-Muslim musical styles of legend, lullaby or sikambang (charm song) singing its style.

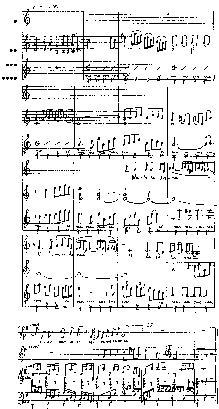

"LAGU SERUNAI ACEH"

[TRANSCRIPTION 2].

RECORDED IN PADANG, IN 1974, BY

MARGARET KARTOMI.

TRANSCRIBED BY GREGORY HURWORTH

AND MARGARET KARTOMI.

Note: The accompaniment is transcribed in full with the exception of the 'cello part, which is inaudible in the recording.

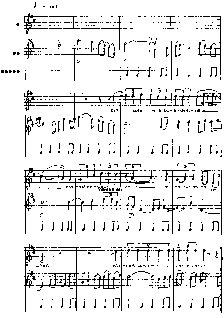

"LAGU KAPRI BANGSAWAN"

[TRANSCRIPTION 3].

RECORDED IN KAMPUNG PASAR SORKAM, IN 1973, BY

MARGARET KARTOMI.

TRANSCRIBED BY GREGORY HURWORTH

AND MARGARET KARTOMI.

• Voice

•• Biola

••• Guitar

•••• Drums

••••• Gandang

The coastal Malays, who are predominantly Muslim, have been noted for their interest in the sea and their overseas trading activities for at least the past millenium. In this respect they contrast with their Batak neighbours, who have an agricultural lifestyle, are culturally inward-looking, are mostly Christian, speak different languages or dialects, and have different musical traditions, including the ceremonial gondang ensembles, consisting of drums, gongs and reed pipes. For centuries, coastal Malays -in both west and east Sumatra-have regarded the upstream people as being less civilized than themselves. Indeed, their lagu pasisir (coastal music) has little in common with the lagu dalem (inland music). Unlike the Bataks, the coastal Malays have no agricultural rituals, but they have two major life-crisis ceremonies, namely: baby thanksgivings and weddings.

Surprisingly enough, it is not the ancient non-Muslim Malay music and dance that are dominant in these two major ceremonies on the coast; and Muslim music plays no part in them at all. Rather it is Portuguese-influence kapri -style music and dance that is appropriate at the baby thanksgivings and weddings, despite the fact that the west coast dwellers have had only peripheral contact with the Portuguese and that was a few centuries ago.

How is it that a Portuguese-influenced style should have supplanted the indigenous pre-Muslim styles of music and dance performed at the major ceremonies in an area which had no history of prolonged contact with the Portuguese, and that these ceremonies allow virtually no space for the Muslim performing arts, despite its being largely a Muslim area? The mystery can only be solved by looking beyond the pasisir to the centres of Malay power over the past five centuries or so, and viewing the pasisir in its position on the periphery of the Malay world, with its history of interaction between the royal centres in and around the Malacca Strait.

The two musical transcriptions of lightly harmonised songs, which I recorded in Sorkam and Padang (on the west coast of Sumatra) respectively, exemplify the kapri -style typical of the area. Performed by an ensemble comprising a vocalist, a violinist, an optional guitar and gandang (frame drums), kapri -style musical works and dances are a synthesis of Malay and Portuguese elements. They are performed at the life-crisis ceremonies such as baby thanksgivings and weddings. 20Remarkably, they have largely replaced the ancient Malay music and dances in these cerimonies.

Part of a folk ensemble from Biak and Serui areas, in Irian Jaya,

consisting of a tifa (drum), guitars ukeleles and a plucked brass.

Photograph taken in 1991 by Hidris Kartomi.

The most active role ia a kapri -style piece is that of the violin player, who plays a continuous melody, the only periods of relative rest being the long-held tones (See: TRANSCRIPTION 2-"Lagu Serunai Aceh", bars 10-15), when the vocalist makes his entry at the beginning of a strophe. The violin plays an important overall unifying role, providing the introduction, counter-melody to the vocal-line, melodic interludes between strophes and vocal phrases, and a postlude, which includes one of several accepted melodic signals to members of the ensemble to end the piece, for example:

The European characteristics of kapri -style music are mainly Portuguese-derived, though Dutch and/or English musical influence may later have reinforced or modified them. In terms of musical style, kapri music does indeed resemble Portuguese folk music in that both are characterised by their use of mainly major and minor keys, strict alternation between mainly tonic and dominant harmonies, lyrics set to quatrain verses which may often be subdivided into couplets, nostalgic textual content, melodic expressiveness, metric regularity in the accompaniments, oral transmission, a degree of Moorish influence, and the use of the violin, guitar and frame drums. Portugal is well-known for its variety of frame-drums. The pasisir is also noted for its frame drums which are preferred to other drums.

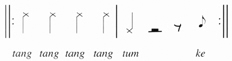

The drum cycles in kapri -style music are called 'tumba', a term combining two onomatopoetic drum sounds called 'tum' and 'ba'. In "Lagu Serunai Aceh", the gandang (frame drum) play the cyclic rhythm:

'Tum' is a low-pitched sound which results from beating in the middle of the skin with the right hand, while 'tang' is a high-pitched sound beaten by the right hand on the edge of the skin, and 'k_' is a high-pitched sound beaten with the left hand. The deep 'tum' tone plays a punctuating role. The 'tumba' establishes a strict metre which offsets the greater rhythmic freedom of the voice and violin. It also determines the tempo of the other members of the ensemble and, with the violin, provides cues for the vocalist's entry which occurs after the third 'tum' beat (see: TRANSCRIPTION 2 "Lagu Serunai Aceh"-bar 11).

The 'tumba', then, is a temporal unit of structural importance; and the most important structural point within the 'tumba' is the 'tum' stroke. The overall formal structure of the song is determined by the cyclic nature of the drum pattern, which means the length of a performance can vary according to the demands of a ritual occasion, the amount of textual repetition indulged by the singer, or the whim of the lead musician.

Lagu orkes gamat (music played on a Malay string and percussion ensemble for dancing couples), in Bengkulu, west Sumatra.

Photograph taken in 1983 by Hidris Kartomi.

Melodic sequences, slurs, turns, accaciatura -like ornaments, and double-stopping, specially at the fourth, fifth and octave, are features of the 'biola' part in a performance of the song "Acehnese Shawm" (See: TRANSCRIPTION 2-"Lagu Serunai Aceh"). The guitar, strumming in C major followed by G major with intervening melodic passages, modulates in bar 5 via pivot note Bb to āminor, which is well established by prolonged double stopping before the vocalist enters, also in ª minor, performing and ornamented melodic part set to a quatrain verse. The frame drum plays a slightly variable eight-beat rhythmic cycle. The vocal and the 'biola' parts in "Royal Kapri Song" (See: TRANSCRIPTION 3-"Lagu Kapri Bangsawan") combine to produce harmonic colour an the tonic, dominant and subdominant, and the drum plays 'tumba' isorhythm.

Finally, the Portuguese presence in Indonesia is partly responsible for the creation of the 'tanjidor' (Port.: tanger, or: to play/pluck a musical instrument) brass band music which is still played in Jakarta and nearby districts, including Bogor, Krawang and Bekasi21 and in Kayuagung area of Sumatra, south of Palembang. 'Tangedores' were originally 'string players', but the word became associated with "[...] open air music to a procession and also a military display [...]."22 In the Kayuagung area, 'tanjidor' bands comprising trumpets, tubas, trombones and drums are played at many weddings and other functions, while in Jakarta they are played "[...] in particular around the new year [...]."23

CONCLUSION

Syncretic Portuguese-Malay musical styles developed as a result of 'white' and 'black' Portuguese contact with Malay coastal areas of Indonesia and the Malay peninsula, especially during the period of Portuguese control of Malacca, between 1511 and 1602. Coastal peoples promoted this music, and in some cases elevated it to the position of the main form of ceremonial music at their major life-crisis ceremonies, such as the Barus area of north-west coastal Sumatra. The musical cultures of most coastal peoples throughout the archipelago are marked by their outward-looking attitudes, their interest in foreign trade and the sea, and their readiness to accept foreign influences. In all these respects, the coastal peoples stand in contrast to their inland neighbours, who by and large continue to practise their traditional ensembles, such as the various gamelan ensembles in Java and Bali, and the gondang and gordang drum and gong ensembles of the Batak region area of north Sumatra.

These styles are creative syntheses of Malay, Portuguese and other elements. Among the Malay elements are the vocal and other melodic ornamentation, the cyclic drum and/or gong periods and rhythms, and the pantun and syair poetic texts, while the Portuguese elements include among other things the harmonic relationships between the violin and the vocal parts, a factor which strongly influences melodic invention.

Portuguese stylistic elements and instruments initially entered the coastal regions of the archipelago via areas which had experienced intense, prolonged contact with the Portuguese. In most coastal areas, however, the musical influences spread by contact between traders and families of Malays living in different areas. Trading contacts and marriages between the Malay royal and commoner families over the centuries resulted in the spread of harmonic Malay music in many coastal areas. Thus the synthesis of Portuguese and Malay elements called kroncong, kapri, dondang, sayang, etc., are each at once stylistically unique and part and parcel of the varied post-Portuguese musical culture of the far-flung coastal Malay world. □

NOTES

1 BOXER, Charles Ralph, The Dutch Seaborne Empire: 1600-1800, London, Hutchinson, 1969, p.11.

2 Idem, p.40.

3 GOLDSWORTHY, David J., Melayu Music of North Sumatra - Ph. D Thesis dissertation 1979, Monash University, Clayton/Melbourne [unpublished].

4 MARDSDEN, William, The History of Sumatra, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1966, pp. 195-196.

5 ANDERSON, John, Mission to the East Coast of Sumatra in 1823, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, 1971, p.292.

6 BOXER, Charles Ralph, op. cit., p.307-Quoting Peter Mundy.

Also See: MUNDY, Peter, Descrição de Macau, em 1637, in BOXER, Charles Ralph, "Macau na Época da Restauração - Macau three hundred years ago", Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1942, pp. 53-75.

7 BOXER, Charles Ralph, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire: 1451-1825, London, Hutchinson, 1965, p.240.

8 Idem, pp. 260-261.

9 ABDURACHMAN, Paramita R., Portuguese Presence and Christian Communities in Solor and Flores: 1556-1630, in [CONFERENCE OF THE ASIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA], Monash University, 1982-[Proceedings of...], p.4-[Unpublished].

10 Idem, p.28.

11 Idem, p.1.

12 ABDURACHMAN, Paramita J., Portuguese Presence in Jakarta, in [SIXTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF ASIAN HISTORY, INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF HISTORIANS OF ASIA], 1974 _ [Proceedings of...], p. 10 _ [Unpublished].

13 KORNHAUSER, Bronia, Kroncong Music in Urban Java- MA Thesis dissertation, 1976, Monash University, Clayton/Melbourne, pp. 108ff.

14 SCHUCHARDT, Hugo, Ueber das Malaioportugiesische von Batavia un Tugu, in "Kreolishe Studien", Wien, (9) 1891, pp. 1-256.

15 KORNHAUSER, Bronia, op. cit., p. 176.

16 HEINS, Ernst, Kroncong and Tanjidor: Two Cases of Urban Folk Music in Jakarta, in "Asian Music", New York, 7 (1) 1975, pp. 20-32, p.24,

17 KORNHAUSER, Bronia, In Defence of Kroncong, in KARTOMI, Margaret, ed., "Studies in Indonesian Music", Clayton/Melbourne, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 104-183, p.7.

18 SANTA MARIA, L., Prestiti Portoghesi nel Maleise Indonesiano, Napoli, 1967, p.43.

19 KARTOMI, Margaret J., Kapri: A Synthesis of Malay and Portuguese Music on the West Coast of North Sumatra, in CARLE, Reiner, "Cultures & Societies of North Sumatra", Berlin - Hamburg, Dietrich (Reimer Verlag), 1987, p.371.

20 Ibidem.

21 HEINS, Ernst, op. cit., p.27.

22 See: Note 12.

23 Ibidem.

*Head of the Department of Music in Monash University, Clayton, Australia. Researcher on the music of Indonesia, Aboriginal Australian music and musicological theory. Author of numerous articles and publications on related topics, including On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments (1990). Awarded membership of the order of Australia for services to Southeast Asian music.