PREVIOUS PAGE:

TANG XIANZU 湯顯祖.

“良辰美景奈何天!賞心樂事誰家院?”(湯顯祖詩句)

“Time and landscape so pleasant! Which is the courtyard with such delights? ”

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1995. Assemblage.

PREVIOUS PAGE:

TANG XIANZU 湯顯祖.

“良辰美景奈何天!賞心樂事誰家院?”(湯顯祖詩句)

“Time and landscape so pleasant! Which is the courtyard with such delights? ”

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1995. Assemblage.

§1. INTRODUCTION TO CHINESE POETRY

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

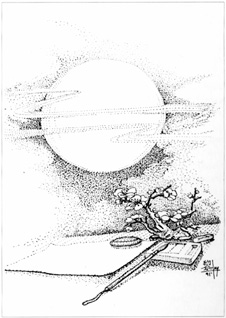

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

Both Chinese and Western poetry are the deepest feelings and sublime expressions of human beings' minds. Without analysing any particular cases, it can be said that Chinese poetry in general followed the pattern of most other worldwide civilisations, literary poems being foremost structured to accompany musical tunes. This concept is firmly documented by the Shi Jing· (Book of Songs) a collection of three-hundred-and-five ancient traditional poems and archaic song lyrics selected among more than three-thousand by Confucius, six centuries BC.

The prolific Chinese literary production during its forty centuries of history, from the legendary era of the Xia· dynasty (1989-1558BC) until present times is documented to have achieved a so far unsurpassed excellence. Infortunately, from the historically known immensely prolific literary production only a fraction has survived to the present, even less having been translated to Western languages, not because of the 'intellectual distance' between cultures but mainly due to the extreme difficulties which have always arisen from rendering the Chinese ideogrammatic language into another idiom.

The first obstacle to be overcome by any translator is the intrinsic structure of the Chinese written language, which is conceptually remote from the alphabetically structured Western idioms. The Chinese language is ideographically monosyllabic, its written form being ideograms graphically expressed by characters whose suggestiveness is much wider that any diccionary would have been able to cover. Accrued to the immediately interpretative problems are hypothetical grammatical interpretations regarding the intrinsic meaning of the characters (or vocables) which frequently, with the same writing, have distinct dictions thus implying different nouns, adjectives and verbs.

Both Chinese nouns and adjectives are characterized by being devoid of number (singular or plural) of gender (feminine, masculine or neutral), this ambiguity being of foremost difficulty in the translations to languages where nouns and adjectives are inexorably and directly qualified by number and gender.

But once this step is overcome the translator faces the decision of giving a temporality (past, present, future) to the narrative action, something which is equally absent in the Chinese language, where verbs are uniform and invariable thus comprehending the whole range of the declinations of the verbs of the Western alphabetic languages. The notion of time being fundamentally different between an Eastern ideogrammatic language and a Western alphabetic language, the 'correct' interpretation of Chinese written tenses must be extracted from the ideologic structure given by the author to each sentence as a whole.

A further difficulty for the translator is that, in classic Chinese, poetical compositions the verses are devoid of pronouns and only rarely the protagonist of the action in mentioned in the descriptive discourse. Not that these poems are to be understood as detached from the involvement of their authors but simply because rather than it being explicitely determined it is merely implied by the meaningfulness and suggestiveness of the 'verbs'.

From this succint list of problems which are a hindrance to any complete translation from Chinese to any Western language, it can be understood that the rules of syntax from both cultural 'systems' vastly differ, and even more so those of comparative literary interpretation. Chinese figures of style, cultural allusions, historical references, and legendary and mythological allusions are remote from any Western sources such as the Greek and Roman civilisations. The same thing applies with reference to traditional cults and sacred symbolisms, either profane or erotic, which usually result as being incomprehensible to a translator less knowledgeable of the numerous intricacies of the millenary Chinese culture, and which frequently require to be profusely annotated for the sake of the general reader.

But the most difficult problem to be overcome by the tranlators of Chinese classic poetry is the laconic mode of its prose and the apparent simplicity of its structure. As a general rule most Chinese classic poems are quite succint, complying to a prescribed rhythm of verses in rhyme, and with a pre-determined number of either five or seven characters (or syllables) per line (or verse) which aim at comprehensively expliciting the idea or poetical message that the author wants to communicate. Chinese classical poetry is frequently said to be 'sober' and 'succint' althought its succintness is nothing but apparent as the sobriety of its characters imply much more than their intrinsic meaning. Each poem may be compared to a painting which the reader can absorb in a number of ways, sometimes extracting from it joyful and stimulanting comparisons, or sad memories tinted by emotion and tenderness. Equally important is the sonority of the verses' diction which should ideally resemble the percussion of pearls rythmically falling on a jade xylophone and threaded by a raphsodic string, thus constituting an incomparable necklace of exquisite beauty. Such poetic linguistic structure of verses condensing such an ample profusion of assertions is unique in the whole world.

Let us analyse an example, the poem entitled Yesi·(Night Thought) by the Chinese master poet Li Tai Bo.· It is a short poem with only twenty characters, appreciated by all Chinese for its succintness and expressive beauty. Chinese emigrants are particular attached to this poem whose four verses express a tender and sorrowful longing for homeland.

The translation of a Chinese classical poem can not merely follow the alphabetical signifiers given in a dictionary for its constituent characters, but must take into consideration the emotional charge of the poem as a whole as understood by a Chinese native, bearing in mind that the language of a race is the most direct way of expressing and exchanging common factors of its behaviour and lifestyle. The translator of a Chinese poem should foremost attempt to feel and think as a Chinese.

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

The transliteration of the following poem respecting the order of the characters is:

夜思

Ye si (Yesi)

Think Night (Night Think).

1.

床 前 明 月 光

Chuang qian ming yue guang

Bed Before Bright Moon Shine

2.

疑 是 地 上 霜

Yi shi di shang shuang

How To be Frost Over

Ground

3.

舉 頭 望 明 月

Ju tou wang ming yue

Raise Head See Bright Moon

4.

低 頭 思 故 鄉

Di tou si gu xiang.

Lower Hear Think Old Village.

The result of such a literal English translation is so inarticulate and inexpressive that it is quite unpoetical. Besides, this translation is just a figment of the poem's comprehensive meaning, not giving clues to its diction, structure, and suggestiveness that its content conveys to a Chinese reader. From this very simple example it can also be immediately understood that a solution in search of an ideal rendering of a classical Chinese poem in a Western language would not be a literal translation of its original Chinese; and that many of its elements must remain nontranslatable. Among others, the greatests losses of this type of transliterated translation are the rhythm, rhyme, musicality and metric integral to the original. Equally important is the visual expressivity of the poem's written characters as the brushwork calligraphy of written characters are as integral for the appreciation of a Chinese text as the virtuosity of the pictorial media is to the full enjoyment of a Western painting.

Is seems extraordinary to admit that such a short poem might contain such unsurmountable problems to the English translator - and to the Spanish, and Portuguese... - but its original structure encapsulates such intricate, and sometimes disconcerting, complexities that its translation requires great skill and an arduous deliberate procedure.

The method followed by some translators of creating a particular rhythm and rhyme to a Chinese poem according to the 'aesthetic ideals' which apply to traditional Western poetical canons can not be considered as adequate, because the fundament of classical Chinese poetry are altogether different.

The exemplified poem is one of the better known ones of Li Tai Bo. The poet wrote it in exile, distant from his beloved homeland. Because of its succintness it has been felicitously adapted to most Chinese dialects and is known by all Chinese nationals.

The poem pungently expresses the heartfell lament of the poet's tormented soul, claiming his sadness and his desolate situation. The author laconically conveys his bitterness with vividly suggestive and symbolic characters, which in succession imaginatively present bright and colourful 'tableaux' of human life and sensations. The author's expressed feelings are an 'echo' and are deeply in tune with the deepest sentiments of the Chinese people.

For exemple, for the Chinese, the "moon" besides being a symbol of feminine physical beauty is also suggestive of 'conjugal love', of 'happiness at home', of 'a united family', 'the strong friendship between old friends', of 'the deep brotherhood links of consanguineous affiliation', of 'a peaceful and happy abode', of 'the cherished homeplace'... and much more. The image of the 'moon' is a world of abundant imagination to any Chinese: vision of light and shade, memories of bygone times in the company of cherished members of their family and deceased relatives, and the always nostalgic sites of their adolescence.

The unadjectivated "bed" is suggestive of 'times of solitude', 'years of loneliness', 'much hardship' and 'obligatory separation from the beloved consort'. The "frost" symbolises 'much sorrowful and doleful weeping'. "Raised [...] head" figuratively means 'to fully understand the consequences of one's decisions bearing in mind possible anguish and suffering'. "Native land" suggests that one's roots truly are in the place of one's parents and family, both dead and alive; that very special place where one returns when old, aspiring to be buried among one's ancestors and to be later venerated -as all the others of his kin - by future generations.

What has been so far stated implies that no strict rules can be applied to the translation of classic Chinese poetry, rather that it is the exclusive responsibility of each translator to elaborate upon the skeletal translation of an original poem -destitute of most of its untranslatable linguistic and structural 'meat and flesh' - explicating to his/her best abilities the attributes he/she selects to emphasise from the overall meaning of the original.

The described restrictions appended to the translations of Chinese poems do not invalidate the efforts taken in translating them. Taking in consideration that the foremost intention of any Western translation of a Chinese poem is always to render the 'spirit' or its original according to a vision of its author - if only partial and fragmented - it is interesting for any Western language reader incapable of deciphering the Chinese text to compare different translations of the same original - both in the same language and in different languages, i. e., French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, etc. - to obtain the widest possible facets of the poet's compositional virtuosity.

In order to better exemplify this point there follows three examples in English, two in Spanish and one in Portuguese of the same mentioned poem by Li Tai Bo.

"Over my bed the moonlight streams,

Making it look like frost-covered

ground; lifting my head I see

the brightness, then dropping it

and I am filled with thoughts of home."

(Translated by Rewi Alley)

"The moonlight lies bright before my couch

I wonder if it were frost on the ground.

Raised my head and gazed at the bright moon,

I hang my head, thinking of my native land."

(Translated by Sun Yu)

"Before my bed

there is bright moonlight

so that it seems

like frost on the ground.

Lifting my head

I watch the bright moon,

lowering my head

I dream that I'm home."

(Translated by Arthur Cooper)

And in Portuguese:

"Pensando à noite

Os raios do luar em frente do meu leito.

Estará o chão coberto de geada?

Levanto a cabeça, ollho a lua,

Baixo a cabeça, penso no meu lar."

(Translated by António Graça de Abreu)

Although the above four translations closely follow the instrinsic meaning of the characters of the Chinese original, they only remotely convey to the Western reader the feelings experienced by the a Chinese when reading it, or better, reciting it, who imaginatively visualizes the symbolic representation of the ideograms, delighting in the exquisite structure of their composition which precisely expresses the nostalgic pain and the sorrowful sentimentality of those isolated in remote exile.

This enchantment derives from the rememberance that the author prosaically shares with the reader, suggestively describing the desolate scenario where he himself, as protagonist of his verses, wondrously broods over the past. In diction and vision, that is, sonorously and caligraphically, through the succession of the characters the poet paints a scene of solitude with reinforcing imagery: first, a cold empty bed, and then, the paleness of the "moon [glowing on the] ground" resembling shining frost.

In the following two Spanish translations I have attempted to explicit different alternatives that a translator might pursue in order to explicit particular facets which are intrinsic to the contents of the original poem. The first succint version follows, with some minor variants, the structural linguistic composition of the Chinese original and the interpretation of the previous four translations.

"Nocturno

Frente a mi cama estampa su fulgor la luna...

¿ No será escarcha que blanquea el suelo?

Alzo la vista, y miro que la luna brilla;

bajo la vista, y pienso en el hogar que anhelo."

The expanded second version attempts to express much more closely the bitter sentiments of the protagonist that a Chinese reader recreates when remembering the poem, specially when distant from his/her homeland.

"Nocturno

Blanco, el claror de luna se extendía

frente a mi lecho, yerto y desolado,

y pensé, al sentir la noche fría,

que acaso en ese sitio había nevado.

Alcé la vista, y vi que refulgia

la luna con hermosa claridad,

y sentí una letal melancolía

al verme immerso en hosca soledad.

Bajé anonadado la cabeza,

cerré los ojos y quedé a pensar:

recordé con nostálgica tristeza,

mi vieja aldea y mi añorado hogar."

§2. THE SYMBOLISM OF CHINESE POETRY

Most of the time in classical Chinese poetry the author explicits the protagonist or the objects which are the theme of his composition through his own emotions and feelings and, in association with traditional symbolism which is commonly known to average Chinese people, suggestively making reference to the complexities of the theme, leaving up to the reader the pleasure of mentally elaborating the several interpretative levels of the composition.

The intrinsic graphic composition of Chinese characters always contain more interpretations that those listed in the best dictionaries. For instance, the ideogram chou· (sadness) is composed by qiu· (autumn) and san· (heart), meaning that one's heart is distressed by the arrival of autum. This season is considered by the Chinese as the saddest of the year because it is when Nature dies. Let us analyse another example. The ideogram yu (jade) equally expresses the ideas of beauty, finesse, preciousness, youth, etc. Confucius considered jade as the symbol of justice, intelligence, kindness and harmony. For him, a zhen ru· (superior man) should have all the qualities of jade.

With the passing of time jade came to acquire other meanings as, jewellery, perfection, smoothness, beauty, youth, and charm, besides many ther connotations.

Let us consider now the incomparable poem by Li Bo entitled Yu jie yuan·(The Sorrow of Jade Steps). It is a short composition of only twenty characters (or ideograms, or syllables), but so carefully selected that through them the poet evokes a situation full of life, colour and feelings.

The transliteration of this poem respecting the order of the characters is:

玉 階 怨

Yu jie yuan (Yujie yuan)

Jade Steps Sorrow (The Sorrow

Jade Steps)

1.

玉 階 生 白 露

Yue jie sheng bai lu

Jade Staircase Born White Dew

2.

夜 久 侵 羅 襪

Ye jiu qin luo wa

Night Old Wet Silk Stockings

3.

欲 下 水 精 簾

Yue xia shui jing lian

Withdraw Lower Water Crystal Curtain

4.

玲 瓏 望 秋 月

Ling long wang qiu yue.

Beauty Gaze Autumn Moon.

This poem is devoid of pronouns. But neither does it make the slightest reference to the protagonist of the situation. Merely using a small number of conventional symbols, the poem describes the place where the action occurs, quite extensively the emotional condition of the protagonist, her social status, sex and age, and with a few 'master strokes' the summit, the gradual decadence, and the end of a person. Let us attempt a further research subdividing it by subjects [see: p. 124]:

1. THE PLACE: the "jade steps" is a way of suggesting the 'imperial harem', 'jade' symbolically meaning a 'young and beautiful woman'. The alcove where she enters and lowers the "crystal [beaded] curtain" is once again merely suggested as neither the verb 'to enter' nor the noun 'alcove' are explicitely mentioned.

2. THE ENVIRONMENT: Extremely cold, as the "[...] dew [glistened] coldly on the jade steps [...]" although this phrase together with the following "[...] the chillness soaks her silk stockings [...]" equally means the 'indifference of imperial repudiation'.

3. THE TIME: The descriptive "[...] late at night] associated with "glittering autumn moon [...]" symbolically means that the protagonist had been expecting for a long time her sad and inevitable fate.

4. THE PROTAGONIST: It is not mentioned but both "jade steps" and "silk stockings" are feminine attributes. The person is therefore of the female sex.

5. STATE OF SPIRIT OF THE PROTAGONIST: The small sections "[...] white dew glistens coldly" [and] "curtains of glittering crystals [...]" attest her great distress, being consumed by terrible uncertainty, and her sorrowful frozen tears.

6. THE ACTION: The misery of the situation is accentuated by its slow-motion tempo, revealed in the images of "[...] sitting [...] the chillness soaks her silk stockings [and coldly on the jade steps [...]". It is implied that she retires to her alcove and mechanically "lets down the curtains [...] gazing [...] musing [...]" It is possible to recreate the reflective woman contemplating her own image on the mirrored "[...] curtains of glittering crystals [brightly lit by the] glittering autumn moon [...]."

7. THE SOCIAL STATUS OF THE PROTAGONIST: This is undoubtedly expressed in "the curtains of glittering crystal", in ancient China the curtains of the imperial harems were textured with rock crystal beads. This woman ("silk stockings") was therefore a concubine. What makes her so special is that she was not a normal household secondary wife but a concubine who had reached the topmost echelons of the imperial harem by virtue of her beauty and her charms. But gradually, with the passing of time, she started to be out of favour with the emperor ("chilliness") and to descend ("steps") from that privileged position she had once held, to be finally left in complete oblivion ("glistens coldly").

But the courtesan's greatest sorrow was being destitute of all favours and honours. This is expressed by the poet portraying the protagonist as a woman in "silk stockings", even without shoes so much less well dressed with any exquisite garnment with which she had once worn in her days of former glory.

In imperial China, all male members of the nobility as well as all the high ranking officers and military patents wore robes with specific embroidered medallions and jade insignia according to their respective ranks. From the Empress to the most humble concubine all women wore specially coloured silk robes and displayed jewellery and adornments according to their status at Court. [...] The third verse the poem "Yu xia shui jing lian", ("let[s] down the curtains of glittering crystals") symbolically, yet clearly, states that the unfortunate concubine had reached the lowest level of the imperial harem. [...]

So, the author as a painter with just a few brushstrokes, evokes the whole lifestory of an imperial favourite concubine, and not of an "empress" as the great Portuguese poet António Feijó describes her in his extremely personal interpretation of this poem, much less as "[...] a lady of the highest aristocracy who, in vain, waits for her beloved in the cold steps of a jade staircase [...]" of another careless translation made with total disregard for the deep symbolism of Chinese poetry.

8. HER AGE: The symbolic phrase ("white dew") "bai lu" besides meaning 'abundant tears' was also in the old Chinese lunar calendar a median period which presently corresponds in the Gregorian calendar to early September. Another symbolic phrase "qiu yue " ("autumn moon") explains much more precisely her age because 'moon' as has been explained is a figure of speech for 'feminine beauty' and 'autumn' is the decline in years of one's life.

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

The poet, leaving the woman contemplating the splendours of the "autumn moon", closes with admirable succintness his short symbolic poem.

The five characters of the last verse suggest that she had become lost in deep thought on the sweet memories of the past, and at the same time with her heart full of sadness and pain by her fall into oblivion in the imperial harem. "Autumn moon", besides meaning 'memories' and 'remembrance of happy times', equally means 'sadness', and the 'end of something which one holds precious and dear in life'.

The ending: "[...] autumn moon." also signifies in this particular circumstance 'sadness' and 'insecurity', because it was in qiu yue (the autumn months) that in ancient China, the executions of criminals and heavy tribunal sentences took place.

In order to be able to describe so well, physically and sentimentally, this woman and because he was at the service of the Ming Huan emperor for quite a number of years, one may hypothesise that Li Bo most probably knew her personally. During his residence at Court he would certainly notice the state of sadness and insecurity of the concubines of the imperial harem.

In fact, during Li Bo's times, Chinese emperors besides being married to the Empress and having a number of consorts, and a number of favourites, also kept a harem of numerous concubines which reached more than three-thousand women. Because of these excesses there were times when poets and literati voiced these prerrogatives being immoral and against the laws of Nature, and therefore contrary to the teachings of Dao and with serious consequences to good government.

In these circumstances, 'immorality' comprised many young girls who spent most of their adolescence and, sometimes all their entire lives, in seclusion and oblivion, sequestred in the imperial harems; most of them without ever getting an opportunity even to go near the imperial quarters. Many, while still young and beautiful, were given as peace-making gifts to the chiefs of the warring tribes which threatened the Chinese borders, and offered to army officers and high dignataries. But most frequently of all they were sent back to their families or simply 'released' from their duties when another batch of 'fresher' women arrived. There were years when more than five-hundred girls were conscripted from all over the empire to serve in the ruler's harem.

Let us now examine two English translations of the poem:

"The Sorrow Jade Steps

The white dew glistens coldly on the jade steps outside,

Sitting late at night, the chillness soaks her silk stockings,

She lets down the curtains of glittering crystals,

Gazing at the glittering autumn moon, musing..."

(Translated by Sun Yu)

"On the Jade Steps

On the Jade steps

in front of her room,

in the night she stands

with the dew wetting

her socks, so that she

goes back into the house

pulling down the bright

crystal screen through

which she gazes

at the autumn moon."

(Translated by Rewi Alley)

Followed by three translations in Portuguese:

"Escada da Desilusão

O tapete de orvalho, que cobre a escadaria,

Humedece os sapatos de seda, em nossos pés.

Brilha a pálida Lua, atravéz dos cortinados

Que descem, portadores de atróz desilusão."

(Translated by Francisco de Carvalho e Rêgo)

"Queixa das Escadas de Jade

Nas escadas de jade cresce

Ainda o branco orvalho,

O frio que toda a noite

Encharcou umas meias de seda.

Ela desce

A persiana de cristal

E contempla a Lua

- envidraçada - do Outono."

(Translated by Gil de Carvalho)

"Lamento nos Degraus de Jade

Os degraus de jade

cobrem-se de geada branca.

O frio da noite

atravessa suas meias de seda.

Baixa então

a cortina de pérolas de cristal

e, atravéz do límpido painel,

enleia o olhar na Lua do Outono. "

(Translated by António Graça de Abreu)

Five translations, all different, even in their titles.

A curious point is that not one of them makes reference to the ideogram shang • (to be born, to live, to emerge, to grow, to produce), which appears in the first verse and has here as its explicit subject the "jade [steps]" staircase of the imperial harem.

Finally a Spanish version of mine which takes into account the symbolic categories already explained:

"Llanto en el Harén

La escala del harén, por largas noches,

blanqueándose, despacio, relucía,

por la escarcha causada por su llanto,

pues tan sólo ya en medias descendía.

Consciente de que todo terminara

al bajar la cortina de cristal,

anondada queda contemplando,

cual su imagen, la luna otoñal."

To summarise: the poet, with four verses of five ideograms (or syllables) each, describes in powerful symbolic hues a situation of astonishing realism, full of life, movement, luminosity and emotion. It is because of these factors that Chinese classical poetry is so difficult to translate, in effect, virtually untranslatable, if one interprets to its strict parameters the vocable 'translate', bearing in mind that language is the foremost specific method of communicating the feelings, expressiveness and ways of life of a civilisation.

Dictionaries are indeed secondary tools in this arduous task!

Translated from Spanish by: Carlos Gonçalves

Untitled.

ADRIÁN LAY RUIZ

1991. Ink on paper.

* Mexican Sinologist of Chinese origin. Lived in China for twelve years and thirty in Macao. In Macao his poems where published in the periodicals "A Voz de Macau", "Religião e Pátria" and "O Clarim". Back in Mexico he contributed for the periodicals "El Occidental", "Fiesta Brava" and "El Gallo", of Guadalajara; and "El Heraldo", of Mexico City.

start p. 117

end p.