An interpretation to this poem has just been proposed. However, in the poem, the narrative elements are no more that a few neutral action verbs, while the words describing feelings such as 'solitude', 'deception', 'frustration', 'regret', the 'desire of the encounter', etc., are totally absent. The personal noun, as prescribed by Chinese poetical tradition is equally absent. Who speaks? A 'she' or an 'I'? The reader is invited to reenact the feelings of the protagonist 'from the inside'; although these sentiments are only suggested by gestures and a few objects.

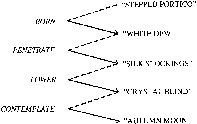

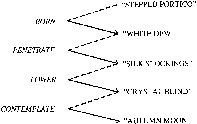

The poem presents itself as a sequence of images: "Jade stepped portico", "white dew", "silk stockings", "crystal blind", 'ling-long'· ("through transparency"), "autumn moon". A reader aware of the Chinese poetical symbolism will have no problem in extracting its connotative meaning:

"JADE [STEPPED] PORTICO" = cold night, lonely time, tears; and a certain erotic nuance as well;

Although initially evoking the jingling sound of the jade pendants, it is also used to qualify precious and sparkling objects, as well as faces of women and children. In this context it stands for a double meaning: for the woman who stares at the "moon" and for the "moon" which lights the woman's face. From a phonal point of view the sequence of words contained in the preceding verses, are words which successively start with the letter '1' and stand for 'shining' and 'transparent objects': lu. ("dew"), luo• ("silk"), and lien• ("crystal blind"); and "AUTUMN MOON" = distant presence and desire of reunion (distant lovers may look at the moon, at the same time; and because of this, the full moon symbolizes the 'reunion of loved beings').

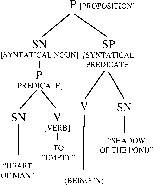

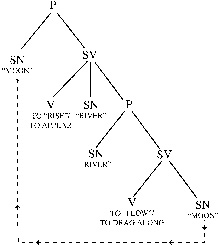

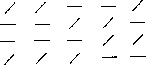

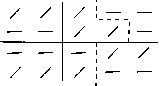

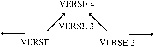

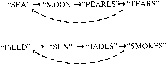

Through this sequences of images the poet creates a coherent world. The linear progression is sustained at a metaphorical level. What all these images have in common is that they all represent 'shining' and 'transparent objects'. Each one of them seems to derive from the precedent, in a regular sequence. This sensation of regularity is confirmed in the syntactical level by the regularity of the phrases of identical typology. The four phrases which constitute the poem can all be analyzed by the same diagram:

Such a regularity imprints the poem with nuances of an inexorable order: in each of the four phrases, the verb is situated at the centre, is determined by a complement and leads to an object. Bearing in mind the omission of the personal subject, the poem stands as part of a process of chained connections and where, successively, one image progresses to the next, from the first to the last.

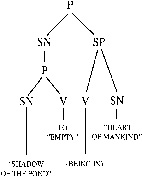

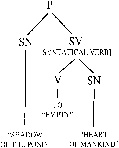

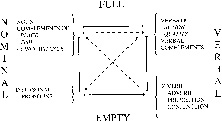

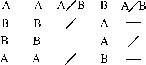

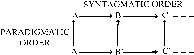

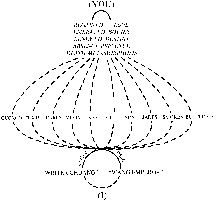

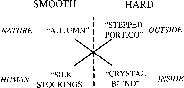

This diagram suggests a linear progression in a single direction. But from an imaginary 'viewpoint', the last image ("moon" light) could be connected to the first ("stepped portico") passing through all the others:

This diagram suggests a linear progression in a single direction. But from an imaginary 'viewpoint', the last image ("moon" light) could be connected to the first ("stepped portico") passing through all the others:

"Ling-long " is at the same time the 'face of the woman who stares' and the "moon" seen through the "crystal blind"; and this "moon" is at the same time 'a distant presence' and 'an intimate feeling', which provokes in each of its associations with the mentioned objects a new sensation.

"Ling-long " is at the same time the 'face of the woman who stares' and the "moon" seen through the "crystal blind"; and this "moon" is at the same time 'a distant presence' and 'an intimate feeling', which provokes in each of its associations with the mentioned objects a new sensation.

.

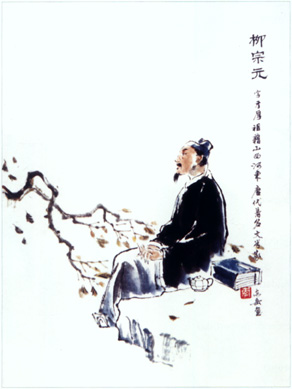

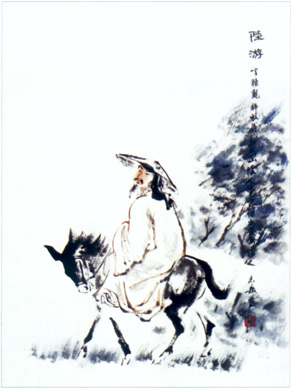

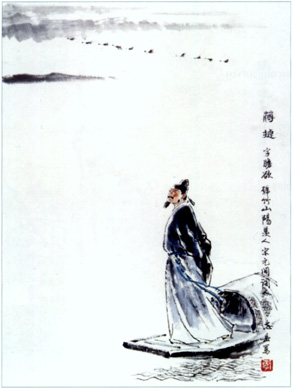

Aliases: Sheng Yu 勝欲, Zhushan 竹山.

<I>Ci </I>poet of the Song (960-1279) and Yuan [1279-1368] dynasties.

LEI CHI NGOK 李志岳 LI ZHIYUE

1995. Colour inks on rice paper. 23.0 cm x 33.0 cm. </figcaption></figure>

<p>

Making use of a metaphorical language, we could perhaps say that beyond a )

Translated from the French original by: Dominique Audart

** Revised reprint from: CHENG, François, L'Écriture Poétique Chinoise Suivi d'une Anthologie des poèmes des T'ang Èdition révisée em 1982, Paris, Èditions du Seuil, 1982, pp.11-191 [lst edition: 1977].

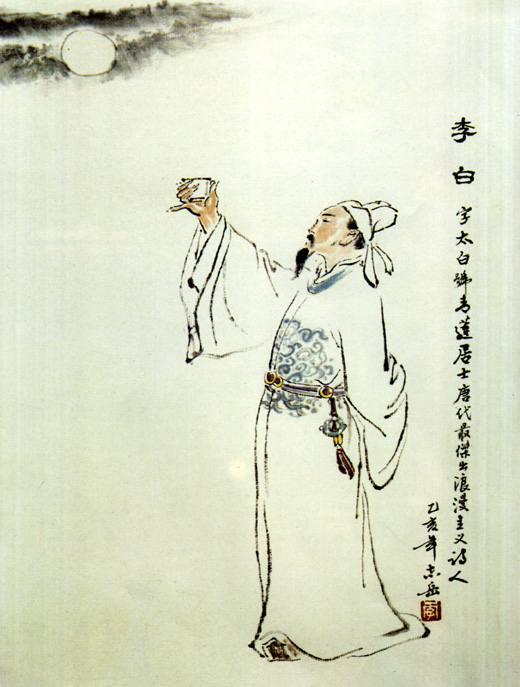

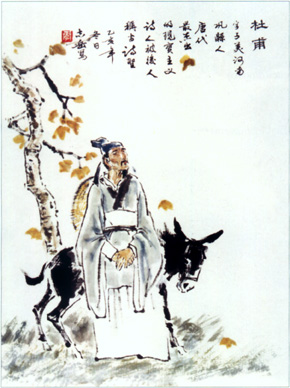

** In this collection of "Chinese Poets"'s ink drawings, each English subtitle follow the text of the original Chinese colophon pertaining to the respective illustration.

NOTES

Translator's introductory note:

TEXT: In a number of cases, the impossibility of coherently reverting into English both the supporting French transliterations/translations of Chinese poems/extracts of poems/titles of poems in the TEXT and their respective and their basic explanatory TEXT, due to grammar and syntax discrepancies between the French and the English languages, led to the overall standardization of including the French transliterations/translations of Chinese poems/extracts of poems/ titles of poems followed by their respective English transliteration/translation.

NOTES: Discrepancies between French transliterations/ translations of Chinese poems/extracts of poems/titles of poems in the TEXT and in the respective NOTES were kept according to the basic French edition. For comparative reference, whenever possible, an English version of the same poem/extract of poem/title of poem follows its respective French version.

Extracts of poems quoted by the author in the TEXT and repertoried in the NOTES, are underlined and contextualised in each corresponding poem, in full, according to their respective French version. English version of poems/extracts of poems/titles of poems in the NOTES are respectively complementary and not coincidental to their respective poems/extracts of poems/titles of poems in the TEXT.

1 The first known specimens of Chinese writing are divination texts on bones and tortoise shells. Archaich bronze ritual vessels also display inscriptions. These two types of writing were practised during the Shang• period (XVIII-XI centuries BC).

2 The Shih-ching (Book of Songs) was the first compilation of 'canticles' of Chinese literature. It contains works dating as far back as the first millenium BC.

3 We are not dealing here with a presentation exclusively based on etymology. Basically, our viewpoint is semiological: above all, what is here attempted is to explicate the signific graphic connections which exist between the signs.

4 Regarding the way in which are understood - either explicitely or implicitely, and according to traditional Chinese rhetoric - the linguistic signs and their functions (a problem which going beyond the parameters of this research, deserves to be systematically studied), the following works should be consulted: the Wen-fu by Lu Chi (AD°261-†303), and the Wen-hsin tiao-long. by Liu Hsieh. (AD°465-+522). What must be here, above all, underlined is the affirmation of mankind as an element of the universe. Mankind together with the sky [Heaven] and the Earth constitute the San-t'ai• (Three Geniuses). These have between them an interrelationship of complementarity and correspondence. The role of mankind consists not only to inhabit the universe but to interiorise all matters, recreating them so that mankind may reassert itself within the the universe. In the process of 'co-creation', the central element of of the literary realm, is the notion of wen •. This concept was to become part of numerous characters meaning 'language', 'style', 'literature', 'civilization',-etc. Originally wen meant the 'imprint' left by some animals, the 'grain' of wood and the 'veins' of stones, an ensemble of harmonious and rhythmic 'traces'; signifiers of Nature. The creation of language signs (equally called wen) derives from the image of these 'traces'. In a certain way, this double origin of wen, constitutes a guarantee to mankind in the unravelling of the mysteries of Nature, and through these, of the 'nature' of mankind itself. This 'vital flow' which animates and reconstitutes the relationships between all matter certainly is a masterpiece!

5 詩成泣鬼神 Shicheng qi guishen.

6 The image of the 'eye' is of foremost importance in Chinese artistic conception. Regarding painting, it is pertinent to remember the anecdote of the painter who always drew eyeless dragons. To all those who questioned him about this strange practise he would invariably reply: - "Because at the moment I add the eyes the dragon would immediately take flight!"

7 Concerning this notion, we give the example of a verse by Li Ho: 筆補造化天無功 Bibu zaohua tian wugong ("When the brush perfects Creation, Heaven is not totally meritorious!").

8 Wang Wei: Hsin-i wu.

9 These two ideograms intrinsically mean the 'lotus' flower. The poet borrows them here suggesting the image of a 'magnolia' flower which is visually similar to that of a 'lotus'.

10 Tu Fu: Je san-shou.•

Chang Jo-shü: Ch'un-chiang-hua-yüeh-ye.· This poem is studied in detail in my text: Analyse formelle de l'oeuvre poétique d'un auteur des T'ang: Zhang Ruo-xu (Formal analysis of the poetical work of a T'ang author: Zhang Ruo-xu).

12 The theory of the 'primary brushstroke' already expostulated by Chang Yen-yuan (AD°810-†ca880) in his Laiti ming-hua, by was to be developed by other painters, namely Shi T'ao(°1671-†1719) in his Hua-yu lu.

13 Ch'i-yün ('vital flow').

14 Regarding literature, it is apt to remember Ts'ao P'ei's· (AD°187-†225) phrase in his Tien-lun lun-wen:• 文以氣爲主 "Wen I Ch'i wei chu" ("In literature: The primacy of the flow."). This work is generally considered a pioneer of Chinese literary critique. Also in Liu Hsieh (AD°465-†552) Wen-hsin tiao-long's· 養氣"Yang Ch'i" ("Nourishing The flow") chapter.

Regarding painting, we are just adding Hsieh He's (active AD500) famous phrase: "Ch'i-yün sheng-tong"• ("To animate the rhythmic flow.").

15 More specifically, pertaining to Taoist philosophy.

16 The division of words in these two major categories vary according to works and epochs. Although all the major Shih-hua·('On Poetry') consistently debated this problem, it is also true that their authors do not specifically determine categories, these being only defined through the numerous examples that they quote in order to support their arguments.

See: CHENG Tei -MAI Mei-ch'iao's,· Ku-han-yü yu-fahsüeh hui-pien· ―For a comprehensive study on this subject.

17 See: II, pp. 31-32

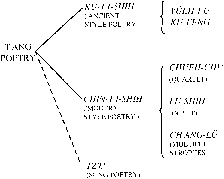

18 The historical situation which conditioned the production of this type of poetry may be resumed as follows: after centuries of internal alliances and the [foreign] invasions which followed the Han dynasty, China was reunified during the T'ang dynasty. Thanks to an efficient administration, the imperial government was able to control the whole nation. However, the archaich structure of a feudal society was shaken by the creation of large scale urban conglomerations, the development of an expanded communication network, and a vast commercial implementation. On the other hand, the recruitment of civil servants through official examinations developed an increasing social mobility. On the cultural level, if the unity of the nation brought again to China the lost consciousness of an internal identity, it also opened the country to multiple external influences, mainly from India and Central Asia. The capital of Ch'ang-an· became a cosmopolitain metropolis where were exchanged numerous intellectual ideologies, thus giving rise to a society concomitantly respectful of order yet effervescent with an extraordinary creative drive.

Despite all, a major event which took place during the years 755-763 came to shake the foundations of the dynasty: the rebellion commanded by a barbarian general called Lu-shan, which caused a great number of deaths and gave rise to all sorts of abuses and injustices. This rebellion brought the dynasty to its end. The poets who lived during this tragic period and those who followed it, produced works which no longer eulogised 'confidence' but expressed a 'deep dramatic state of consciousness'. The theme of their works became centred on the reenactment of survival dramas rather than in the affluent description of social realities. Their works suffered the influence of the evolution of society.

19 This essay being also addressed to those without much knowledge of Sinology, has adapted - among the several transcription systems currently in use - the Wade-Giles system, which remains to the present the most popular and commonly used in the West. On the other hand, we decided to transcribe the words according to the present pronunciation.

[Translator's note: Throughout the text all transliterations were kept according to the French original edition. For a pinyin romanisation of these transliterations see the "Comprehensive Chinese Glossary" at the end of this issue. Entries of this text are made for all words indexed with a superciliary dot (·) according to the transliteration originally given by the author.].

20 We quote [the marquis d'] Hervey Saint-Denys on the difficulty of translating Chinese verses: "In most cases, a literal translation of the Chinese is impossible. Certain characters frequently express a tableau (mood) which can only be expressed by a periphrase. […] In order to be interpreted with validity, certain characters absolutely require a whole phrase. Any Chinese vers (verse) must be first [attentively] read; and in order to be able to grasp its prevailing trait (mood) and to retain [in the translation] its force (strength) or couleur (hue) [the reader] must become imbued by the image or thought in contains. It is a dangerous task: pityful as well, when [the translator is] fully aware of the intrinsic beauties [of a verse] that no European language is able to express."

21 Following the May Fourth Movement (1911), the literary 'revolution' being strictly connected with the political and social 'revolution', questions once again not only the traditional ideology but also the 'instrument' of literary expression.

22 This genre will be analysed in the following chapter.

23 [See: Part. II, p.112]

WANG WEI 王維

鹿柴

空山不見人

但聞人語聲

返景入紳林

復照青苔上

Clos au cerfs

Montagne vide/ ne percevoir personne

Seulement entendre / voix humaine résonner

Ombre-retournée / pénétrer forêt profonde

Encore luire / sur la mousse verte

In: CHENG, François, l'écriture poétique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poémes des T'ang, Paris. Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.112.

Deer Park

Hills empty, no one to be seen

We only hear voices echoed -

With light coming back into the deep wood

The top of the green moss is lit again.

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1973, p.28.

24 [See: Part. II, p.171].

WANG WEI 王維

終南山

太乙近天都

連山到海隅

白雲迴望合

青霭入看無

分野中峰變

陰陽衆壑殊

欲投人宿處

隔水問樵夫

Le mont Chung-nan

Suprême faîte / proche de la Citadelle-céleste

Reliant monts/jusqu'au bord de lamer

Nuages blancs / se retourner comtempler s'unir

Rayon vert / pénétrer chercher s'anéantir

Divisant étoiles / pic central se transformer

Sombre-clair / vallons multiples varier

Désirer descendre / logis humain passer la nuit

Par-delà eau / s'addresser à bûcheron

In: CHENG, François, l'écriture poétique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poèmes des T'ang, Paris. Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.170.

The Chungnan Mountains

T'ai-i nearly touching the Citadel of Heaven

Chain of hills down the edge of the sea

White clouds closing over the distance

Blue haze - nothing comes into view

The central peak transforms the whole tract

Dark and light valleys, each way distinct -

If I want a lodging for the night here

Across the river there's a woodman I may ask.

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1973, p.69.

25 [See: Part II, p.110].

MENG HAO-JAN 孟浩然

春曉

春眠不覺曉

處處聞啼鳥

夜來風雨聲

花落知多少

Matin de printemps

Sommeil printanier / ignorer aube

Tout autour entendre / chanter oiseaux

Nuit passée bruissement / de vent de pluie

Pétales tombées / qui sait combien...

In: CHENG, François, l'écriture poétique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poèmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.110.

The Dawn of Spring

Spring dreams that went on

well past dawn; and I felt

that all around me was the sound

of birds singing; but really

night was full of the noise

of rain and wind, and now I wonder

how many blossoms have fallen.

In: ALLEY, Rewi, trans., Selected Poems of the Tang & Song Dynasties, Hong Kong, Hai Feng Publishing Company, 1981, p.7.

26 [See: Part II, p.207].

LIU CH'ANG-CH'ING 劉長卿

尋南溪敘道士

一路經行處

莓苔見履痕

白雲依靜渚

春草閉閑門

過雨看松色

隨山到水源

溪花與禪意

相對亦忘言

En cherchant le moine taoїste Ch'ang du ruisseau du Sud

Le long chemin / traverser maints endroits

Mousses tendres / percevoir traces de sabots

Nuages blancs / entourer оlot calme

Herbes folles / enfermer porte oisive

Pluie passйe / contempler couleur de pin

Colline longйe / atteindre source de riviиre

Fleurs de l'eau / rйvйler esprit de Ch 'an

Face а face / dejа hors de la parole

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.206.

A Visit to Ch'ang, the Taoist recluse of Nan Ch'i

All my way along the road (to your cottage)

On the mosses I see footprints of your wooden shoes.

White clouds lie low upon the quiet island,

Sweet grasses grow right up to your idle door.

A passing shower brings out the colour of the pines.

Following the hills I come to the source of the stream.

In: JENYNS, Soame, trans., Selections from the Three Hundred Poems of the T'ang Dynasty, London, John Murray, 1940, p. 105.

27 [See: Part II, p. 193].

TU FU 杜甫

又呈吳郎

堂前撲棗任西鄰

無食無兒一婦人

不爲困窮寜有此

只緣恐懼轉須親

即防遠客雖多事

便插疏離卻甚真

已訴徵求貧到骨

正思戎馬淚盈巾

Second envoi а mon neveu Wu-lang

Devant chaumiиre secouer jujubier / voisine de l'ouest

Sans nourriture sans enfant/une femme esseulйe

Si n'кtre pas dans la misиre / pourquoi recourir а ceci

A cause de honte-crainte/au contraire кtre bienveillant

Se mйfier de l'hфte йtranger / bien que superflu

Planter haies clairsemйes / nйanmoins trop rйel

Se plaindre corvйes-impфts / dйpouillйe jusqu'aux os

Penser flammes de guerre / larmes mouiller habits

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.193.

Asking of Wu Lang Again

Couldn't let her filch dates from your garden?

She's a neighbor. Childless and without food,

Alone - only desperation could bring her to this.

We must be gentle, if only to ease her shame.

People from far away frighten her. She knows us

Now - a fence would be too harsh. Tax collectors

Hound her, she told me, keeping her bone poor...

How quickly thoughts of war become falling tears.

In: HINTON, David, trans., The selected poems of Tu Fu,

New York, New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1989, p.97.

28 [See: Part II, p.213].

WANG WEI 王維

月下獨酌

花間一壺酒

獨酌無相親

舉杯邀明月

對影成三人

月既不解飲

影徒隨我身

暫伴月將影

行樂須及春

我歌月徘徊

我舞影零亂

醒時同交歡

醉後各分散

永结無情逰

相期邈雲漢

Buvant seul sous la lune

Pichet de vin, au milieu de fleurs.

Seul а boire, sans un compagnon,

Levant ma coupe, je salue la lune:

Avec mon ombre, nous sommes trois.

La lune pourtant ne sait point boire.

C'est en vain que l'ombre me suit.

Honorons cependant ombre et lune:

La joie ne dure qu'un printemps!

Je chante et la lune musarde,

Je danse et mon ombre s'йbat.

Йveillйs, nous jouissons l'un de l'autre.

Ivres, chacun va son chemin...

Retrouvailles sur la Voie lactйe:

А jamais, randonnйe sans attaches!

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poйmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.213.

Drinking alone with the Moon

A pot of wine among the flowers.

I drink alone, no friend with me.

I raise my cup to invite the moon.

He and my shadow and I make three.

The moon does not know how to drink;

My shadow mimes my capering;

But I'll make merry with them both -

And soon enough it will be Spring.

I sing - the moon move to and fro.

I dance - my shadow leaps and sways.

Still sober, we exchange our joys.

Drunk - and we'll go our separate ways.

Let's pledge - beyond human ties - to be friends,

And meet where the Silver River ends.

In: SETH, Vikram, Three Chinese Poets: Translations of poems by Wang Wei, Li Bai and Du Fu, London - Boston, Faber and Faber, 1992, p.27.

29 麻鞋見天子, Maxie jian Tianzi (Tu Fu: Shu huai·).

30 眼枯即見骨,天地終無情 yanku ji jian gu, tiandi zhong wuqing (Tu Fu: Si-an li·).

31 嵗晚或相逢,青天騎白龍 Suiwan huo xiangfeng, qingtian qi bailong (Li Po: Song Yang-shan-jen kui Songshan·).

32 青天碧於水,畫船聼雨鳴 Qingtian bi yu tian, huanchuan ting yu ming (Wei Chuang: Pu-sa man·).

33 誰家今夜扁舟子,何處相思明月樓 Shuijia jinye bianzhouzi, hechu xiangsi mingyuelou. It is relevant to give here the translations of these two verses. The marquis d'Hervey Saint-Denis: "Nul ne sait mкme qui je suis, sur cette barque voyageuse /Nul ne sait si cette mкme lune йclaire, au loin, un pavillon oщ on songe а moi. ";in the Anthologie de la poйsie chinoise classique: "A qui donc appartient la petite barque qui vogue en cette nuit? / Oщ donc retrouver la maison dans le clair de lune oщ l'on songe а l'absent?"; by Charles Budel: "In yonder boat some traveller sails tonight / Beneath the moon which links his thoughts with home."; and by W. J. B. Fletcher: "To-night who floats upon the tiny skiff? / from what high tower yeans out upon the night / the dear beloved in the pale moonlight…".

34 [See: Part II, p.205].

CH'ANG CHIEN 常建

破山寺後禪院

清晨入古寺

初日照高林

曲徑通幽處

禪房花木紳

山光悦鳥性

潭影空人心

萬籁此俱寂

惟餘鐘磬音

Au monastиre de Po-shan

Matin clair / pйnйtrer temple antique

Soleil naissant / йclairer hauts arbres

Sentier sinueux / communiquer lieu secret

Chambre de Ch'an / fleurs-plantes profondes

Lumiиre de montagne /jouir humeur des oiseaux

Ombre de l'йtang / vider cœur de l'homme

Dis mille bruits/а la fois silencieux

Seul rester/son de pierre musicale

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.205.

At the Hall of Silence in the Monastery of the Broken Hill Zen Temple

I set out to enter the old monastery in the freshness of early morning.

The early sun shines down upon high woods,

A winding path leads to this place of quiet.

Here deep among the flowers and trees is the cell of contemplation;

In the sunlight behind the monastery the birds are enjoying themselves,

The shadows on the pool purge the mind,

All the noise of the world is stilled;

All I hear are the sounds of the Ch'ing and the monastery bell.

In: JENYNS, Soame, trans., A Further Selection from the Three Hundred Poems of the T'ang Dynasty, London, John Murray, 1944, pp.58-59.

35 It is relevant to give here the translations of these two verses. The marquis d' Hervey Saint-Denis : "Dиs que la montagne s'illumine, les oiseaux, tout а la nature, se rйveillaient joyeux: / l'oeil contemple des eaux limpides et profondes, comme les pensйes de l 'homme dont le cњur s 'est йpurй."; H. A. Giles: "Around these hills sweet birds their pleasure take / Man's heart as free from shadow as this lake."; W. Brynner: "'Here birds are alive with mountain-light / And the mind of man touches peace in a pool."; W. J. B. Fletcher: "Hark! The birds rejoicing in the mountain light / Like one'sdim reflection on a pool at night / Lo! The heart is melted wav'ring out of sight."; R. Payne: "The mountain colours have made the birds sing / the shadows in the pool empty the hearts of men."

36 [See: Part II, p.198].

TU FU 杜甫

旅夜書懷

細草微風岸

危檣獨夜舟

星垂平野闊

月湧大江流

名豈文章著

官應老病休

飄飄何所似

天地一沙鷗

Pensйe d'une nuit en voyage

Herbes menues / brise lйgиre berge

Mat vacillant / nuit solitaire barque

Astres tombant / vaste plaine s' йlargir

Lune surgissant / grand fleuve couler

Renom oщ donc / œuvres йcrites s'imposer

Mandarin devoir/vieux malade se retirer

Flottant flottant /а quoi ressembler

Ciel-terre / une mouette de sable

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.198.

Night Thoughts Afloat

By bent grasses

in a gentle wind

Under straight mast

I'm alone tonight,

And the stars hang

above the broad plain

But the moon's afloat

in this Great River:

Oh, where's my name

among the poets?

Official rank?

'Retired for ill-health.'

Drifting, drifting,

what am I more than

A single gull

between sky and earth?

In: LI Po - TU Fu, COOPER, Arthur, trans, intro. and anot., Li Po and Tu Fu, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1988, p.237.

37 It is relevant to give here the translations of these two verses. J. Liu: "The stars drooping, the wild plane is vast / the moon rushing, the great river flows."; W. J. B. Fletcher: "The wide-flung stars overhang all vasty space / the moonbeams with the Yangtze's current race."; K. Rexroth: "Stars blossom over the vast desert waters / Moonlight flows on the surging rivers."

38 See: III, pp. 60-64 - For the analysis of this poem.

39 [See: Part. II, p.203].

LI SHAN-YIN 李商隱

馬嵬

海外徒聞更九州

他生未卜此生休

空閑虎旅傳宵柝

無復雞人報曉籌

此日六軍同駐馬

當时七夕笑牽牛

如何四紀爲天子

不及盧家有莫愁

Ma-wei

Per delб les mers en vain apprendre / Neuf contrйes changer

L'autre vie non prйdite / cette vie arrкtйe

En vain entendre gardes-tigres/ battre cloches de bois

Ne plus revenir homme-coq / annoncer arrivйe de l'aube

Aujourd'hui Six armйes / ensemble arrкter chevaux

L'autre nuit Double Sept/rire Bouvier-Tisserande

Pourquoi donc quatre dкcades / кtre Fils du Ciel

Ne valoir point fils de Lu / avec Sans-Souci

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.203.

Ma-wei

An empty rumour, that second world beyond the seas

Other lives we cannot divine, this life is finished.

In vain she hears the Tiger Guards sound the night rattle,

Never again shall the Cock Man come to report the sunrise.

This is the day when six armies conspire to halt their horses:

The Seventh Night of another year mocked the Herdboy Star.

What matter that for decades he was the Son of Heaven?

He is less than Lu who married Never Grieve.

In: GRAHAM, A. C., trans. and intro., Poems of the Late T'ang, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1965, p. pp.163-164.

40 This is the term used by R. Jakobson in his work: Shifters, verbal categories and the russian verb.

41 [See: Part II, p. 179].

LI PO李白

送友人

青山横北郭

白水遶東城

此地一爲别

孤蓬萬里征

浮雲游子意

落日故人情

揮手自茲去

蕭蕭班馬鳴

Adieu а un ami qui part

Mont vert/border rempart du Nord

Eau blanche / entourer muraille de I'Est

De ce lieu/un fois se sйparer

Herbe solitaire /sux dix mille li errer

Nuages flottants /humeur du vagabond

Soleil couchant/sentiment de l'ami ancient

Agiter mains/en cet instant partir

Hsiao-hsiao/chevaux seuls hennir

In: CHENG, Franзois, I'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.179.

Taking Leave of a Friend

Blue mountains lie beyond the north wall;

Round the city's eastern side flows the white water.

Here we part, friend, once forever.

You go ten thousand miles, drifting away

Like an unrooted water-grass.

Oh, the floating clouds and the thoughts of a wanderer!

Oh, the sunset and the longing of an old friend!

We ride away from each other, waving our hands,

While our horses neigh softly, softly...

In: OBATA, Shigeyoshi, The Works of Li Po the Chinese Poet done into English verse by hi Obata with an introduction and biographical and critical matter translated from the Chinese, New York City, E. P. Dutton & Co., 1922, p.94.

42 明月籠中鳥,乾坤水上萍 Riyue longzhong niao, qiankun shuishang ping (Tu Fu: Heng-chou song Li taifu•).

43 [See: Part. II, p.163].

LI SHAN-YIN 李商隱

嫦娥

雲母屏風燭影紳

長河漸落曉星沈

嫦娥應悔偷靈藥

碧海青天夜夜心

Ch'ang O

Mica paravent /ombre de chandelle s'obscurcir

Long Fleuve peu а peu s'incliner/йtoile du matin sombrer

Ch'ang 0 devoir regretter / dйrober drogue d'immortalitй

Mer йmeraude ciel azur / nuit-nuit cœur

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.203.

The Lady in the Moon (I) Ch'ang O

The lamp glows deep in the mica screen.

The long river descends, the morning star drowns.

Is Ch'ang O sorry that she stole the magic herb,

Between the blue sky and the emerald sea, thinking night after night?

In: GRAHAM, A. C., trans. and intro., Poems of the Late T'ang, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1965, p.155.

44 [See: Part. II, p.210].

WEN T'ING-YЬN 溫庭筠

商山早行

晨起動征鐸

客行悲故鄉

雞聲茅店月

人跡板橋霜

槲葉落山路

枳花明驛

因思杜陵夢

凫鳬雁滿迴塘

Dйpart а l'aube sur le mont Shang

Se lever а l'aube / agiter grelots de mulets

Hommes en voyage / regretter pays natal

Chant de coq / auberge de chaumes lune

Traces de pas /pont de bois givre

Feuilles de hu / tomber route de montagne

Fleurs de chih /йclairer mur de relais

Encore penser / rкve de Tu-ling

Oies sauvages / parsemer йtang en mйandres

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.170.

Setting out Early from Mount Shang

At dawn I rise, stirring my carriage bells.

This traveler goes on, grieving for his home.

Cry of the cock, moon on the thatched inn;

Tracks of someone, frost on the plank bridge.

Oak leaves fall on the mountain road;

Orange blossoms brighten the post-station wall.

And I long for my Dulin dream;

Ducks and geese fill the curving pool.

In: ROUZER, Paul F., Writing Another's Dream: The Poetry of Wen Tingyun, Standford/California, Standford University Press, 1993, p. 18.

45 星河秋一雁,砧杵夜秋家 Xinghe qiu yiyan, zhanchu ye qiujia

46 五湖三畝宅,萬里一歸人 Wuhu san mu zhai, wanli yi gui (Wang Wei: Song Chiu Wei lui-ti·).

47 老年復道路,遲日復山川 Laonian fu daolu, chiri fu shanchuan (Tu Fu: Hsing-ts'u ku-ch'eng·).

48 黃葉乃風雨,青樓自管弦 Huangye nai fengyu, qinglou zi guanxian (Li Shang-yin: Feng yь·).

49 幽薊餘蛇豕,乾坤尚虎狼 Youji yu sheshi, qiankun shang hulang (Tu Fu: You kan·).

50 生理何顏面,憂端且嵗時 Shengli he yanmian, youduan qie suishi (Tu Fu: Te ti hsiao-hsi·).

51 [See: Part. II, p.197].

TU FU 杜甫

江漢

江漢思歸客

乾坤一腐儒

片雲天共遠

永夜月同孤

落日心猶壮

秋風病欲蘇

古來存老馬

不必取長途

Yang-tse et Han

Yang-tse et Han/ voyageur rкvant de retour

Ciel-terre / un lettrй dйmuni

Nuage mince/ciel avec lointain

Nuit longue / lune ensemble solitaire

Soleil sombrant / cœur encore ardent

Vent automnal / maladie presque guйrie

Depuis l'antiquitй / conserver vieux cheval

Pas nйcessairement / mйriter longue route

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 197.

Chiang-han

Traveling Chiang-han, love savant spent

Between Heaven and Earth, I dream return.

A flake of cloud sky's distance, night

Remains timeless in the moon's solitude.

My heart grows still at dusk.

In autumn wind, I am nearly healed. Long ago,

Old horses were given refuge, not sent out.

The long road is not all they're good for.

In: HINTON, David, The selected poems of Tu Fu, New York, New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1989, p.106.

52 [See: Part. II, p.175].

WANG WEI 王維

過香積寺

不知香積寺

數里入雲峰

古木無人徑

紳山何處鐘

泉聲咽危石

日色冷青松

薄暮空潭曲

安禪制毒龍

En passant par le temple au Parfum-Cachй

Ne point connaоtre /temple au Parfum-Cachй

Plusieurs li/pйnйtrer pic nuageux

Bois antique / nulle trace sentier

Montagne profonde / quel lieu cloche

Bruit de source/sangloter rochers dresses

Couleur du soleil / fraоchir pins verts

Vers le soir / lac vide au dйtour

Mйditant Ch 'an / dompter dragon venimeux

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.175.

Visting Hsiangchi Temple

I didn't know Hsiangchi Temple

And went miles into cloudy peaks

Between ancient trees, no tracks of man-

Where was that bell deep in the hills?

Sound of a stream choking on sharp rocks

Sun cool coloured among green pines -

At dusk beside a deserted pool, a monk

Meditating to subdue the poisonous dragon.

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1973, p.94.

53 [See: Part. II, p.195].

TU FU 杜甫

詠懷古跡

群山萬壑赴荆門

生長明妃尚有村

一去紫臺連朔漠

獨留青塚向黃昏

畫圖省識春風面

環珮空歸月下魂

千年琵琶作胡語

分明怨恨曲中論

Sites anciens

Multiples montagnes dix-mille vallйes / parvenir а Ching-men,

Naоtre grandir Dame lumineuse /encore y avoir village

Une fois quitter Terrasse Pourpre / а mкme dйsert nordique

Seul rester Tombeau Vert/face au crйpuscule jaune

Tableau peint mal reconnaоtre / visage de brise printaniиre

Amulettes de jade en vain retourner / вme de nuit lunaire

Mille annйes p 'i-p'a /chargй d 'accents barbares

Clairs distincts griefs-regrets/en son chant rйsonner

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 195.

Thoughts on an Ancient Site

Flock-mountains myriad-valleys arrive Ching-men

Bore-bred Ming-fei still there-is village

Once departed purple-terrace continuous northern-desert

Only leave Green-grave face twilight

Portraits have recorded spring-wind face

Girdle-jade vainly returns moon-light soul

Thousand years guitar makes Hunnish talk

Just-like resentment tune-in discussed

In: HAWKES, David, A Little Primer of Tu Fu, Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong - The Oxford University Press, 1994, pp.176-177.

54 This can be verified in the modern oral language, still presently spoken.

55 [See: Part. II, pp.182-183]

TU FU 杜甫

春望

國破山河在

城春草木紳

感時花濺淚

恨别鳥驚心

烽火連三月

家書抵萬金

白頭搔更短

渾欲不勝簪

Printemps catif

Pays briser / mont-fleuve demeurer

Ville printemps / herbes-plantes foisonner

Regretter йpoque /fleurs verser larmes

Maudire sйparation /oiseaux sursauter cњur

Flammes de guerre / continuer trois mois

Lettres de famille / valoir mille onces d'or

Cheveux blanchis / gratter plus rares

A tel point / ne plus supporter йpingle

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 182.

Looking at Springtime

In fallen States hills and streams are found,

Cities have Spring, grass and leaves abound;

Though at such times flowers might drop tears

Parting from mates, birds have hidden fears:

The beacon fires have now linked three moons,

Making home news worth ten thousand coins;

An old grey head scratched at each mishap

Has dwindling hair, does not fit its cap!

In: LI Po - TU Fu, COOPER, Arthur, trans, intro. and anot., Li Po and Tu Fu, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1988, p. 171.

56 [See: Part. II, p.114]

WANG WEI 王維

鳥鳴澗

人閒桂花落

夜靜春山空

月出驚山鳥

時鳴春澗中

Torrent au chant d'oiseau

Homme au repos / fleurs de cannelier tomber

Nuit calme /montagne printaniиre кtre vide

Lune surgissant / effrayer oiseau du mont

Parfois crier/dans le torrent de printemps

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.114.

Birds calling in the valley

Men at rest, cassia flowers falling

Night still, spring hills empty

The moon rises, rouses birds in the hills

And sometimes they cry in the spring valley

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1973, p.55.

57 Well before the definition of the 'four tones' by Shen Yue· (AD°441-†513), the poets instinctively made use of tonal distinctions.

58 According to Wang Li• in his Han-yь shih-lь hsьeh.•

59 The following diagrams correspond solely to the first half of a pentasyllabic lь-shih - the second half being identical to the first.

60 See: JAKOBSON, R., Le dessin prosodique dans le vers rйgulier chinois. [sic]

61 See: DOWNER, G. B. - GRAHAM, A. C., Tone patterns in chinese poetry. [sic] - Where this diagram was first proposed.

62 See: III., pp. 50-54 - Regarding the metaphorical images.

[Also see: Part II, p. 132].

LI PO 李白

玉階怨

玉階生白露

夜久侵羅襪

卻下水晶簾

玲瓏望秋月

Complainte du perron de jade

Perron de jade / naоtre rosйe blanche

Tard dans la nuit / pйnйtrer bas de soie

Cependant baisser / store de erystal

Par transparence / regarder lune d'automne

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 132.

Marble Stairs Grievance

On Marble Stairs still grows the white dew

That has all night soaked her silk slippers,

But she lets down her crystal blind now

And sees through glaze the moon of autumn

In: Li Po-TU Fu, COOPER, Arthur, trans., intro., anot., Li Po and Tu Fu, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1988, p.112.

63 Corresponds to Li Yь's first strophe of his Lang-t'aosha.·

See: Anthologie de la poйsie chinoise classique: "Derriиre rideaux, la pluie sans fin clapote. /La vertu du printemps s'йpuise./Sous la housse de soie, l'intolйrable froid de la cinquiиme veille! / Quand je rкve j'oublie que se suis en exil. /Doux rйconfort tant attendu!"

64 Han Yu: T'ing Ying-shih t'an-ch'in.•

65 Li Ch'ing-chao: Sheng-sheng man.•

66 [See: Part. II, p.186].

TU FU 杜甫

聞官軍收河南河北

劍外忽傳收薊北

初聞涕淚滿衣裳

卻看妻子愁何在

漫卷詩書喜欲狂

白日放歌須緃酒

青春作伴好還鄉

即從巴峽穿巫峡

便下襄陽向洛陽

En apprenant que l'armйe impйriale a repris le Ho-nan et le Ho-pei [74]

Par delа l'Йpйe soudain rapporter/ rйcupйrer Chi-pei[83]

А peine entendre flots de larmes /inonder habits

Cependant regarder femme-enfants / tristesse oщ setrouver

Fйbrilement enrouler poиmes-йcrits /joie а rendre fou

Jour clair chanter а pleine voix / de plus boire sans retenue

Printemps vert se tenir compagnier /pour retourner au pays

Alors depuis gorges de Pa / enfiler gorges de Wu

Et puis descendre Hsiang-yang / vers Luo-yang [66]

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 186.

On learning of the Recovery of Honan and Hopei by the Imperial Army

Chien-beyond suddenly is-reported recovering Chi-pei

First hear tears cover clothing

Turn-back look-at wife-children sorrow where is

Carelessly roll poems-writings glad about-to-become crazy

White-sun let-go-singing must give-way-twine

Green-spring act-as companion good-to returnhome

Immediately from Pa-gorge traverse Lu-gorge.

Then down-to Hsiang-yang on-to Lo-yang

In: HAWKES, David, A Little Primer of Tu Fu, Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong-The Oxford University Press, 1994, pp. 176-177.

67 See: II, p. 38 [and Part. II, p.205]. The diagonal dash (/) corresponds to the caesura. See: Note 34.

68 [See: Part. II, p. 172].

WANG WEI 王維

山居秋暝

空山新雨後

天氣晚來秋

明月松間照

清泉石上流

竹喧歸浣女

蓮動下漁舟

隨意春芳歇

王孫自可留

Soir d'automne en montagne

Montagne dйserte /aprиs pluie nouvelle

Air du ciel / vers le soir automne

Lune claire / parmi les pins luire

Source limpide / sur les rochers couler

Bambous bruire / rentrer lavandiиres

Lotus agiter / descendre barque de pкcheur

Ici ou lб / fragance printaniиre au repos

Noble seigneur/en soi pouvoir rester

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 172.

In the hills at nightfall in autumn

In the empty hills just after the rain

The evening air is autumn now

Bright moon shining between pines

Clear stream flowing over stones

Bamboos clatter - the washerwoman goes home

Lotuses shift - the fisherman's boat floats down

Of course spring scents must fail

But you, my friend, you must stay.

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1973, p.75.

69 [See: Part. II, p.173].

WANG WEI 王維

使至塞上

單車欲問邊

屬国過居延

征蓬出漢塞

歸鴈入胡天

大漠孤煙直

長河落日圓

簫關逢候騎

都護在燕然

En mission а la frontiиre

Carrosse seul / se rendre а la frontiиre

Pays dйpendant / par-delа Chь-yan

Herbe-errante /sortir dйfenses des Han

Oies de retour / pйnйtrer ciel barbare

Immense dйsert / solitaire fumйe droite

Long fleuve / sombrant soleil rond

Passe de Hsiao / rencontrant patrouille

Quartier gйnйral / au mont des Hirondelles

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise/suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 173.

On a mission to the frontier

Off in a single carriage on my mission to the frontier

For dependencies beyond Chьyen now

I am carried like thistledown out from the Han defenses

And wild geese are flying back to the savage waste

From the Gobi one trail of smoke straight up

In the long river the falling sun is round

At Hsiao Pass I meet our patrols

Headquarters are on Mount Yenjan.

In: WANG Wei, ROBINSON, G. W. trans. and intro., Wang Wei: Poems, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1973, p.75.

70 江流天地外,山色有無中 Jiangliu tiandi wai, shanse youwu zhong (Wang Wei: Han-chiang lin fan·).

71 [See: Part II, p.107].

WANG CHIH-HUAN 王之渙

登鸛雀樓

白日依山盡

黃河入海流

欲窮千里目

更上一層樓

Du haut du pavillon des Cigognes

Soleil blanc / le long des monts disparaоtre

Fleuve Jaune /jusqu'а lamer couler

Dйsirer йpuiser / mile li vue

Encore monter / un йtage

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 107.

An Ascent to Stork Hall

The setting sun behind the mountain glows,

The muddy Yellow River reawards flows.

If more distant views are what you desire,

You simply climb up a storey higher.

In: XU Zhongjie, trans., ed., 200 Chinese Tang Poems in English Verse, Beijing, Beijing Languages College Publishers, 1990, p.32.

72 WANG Li, Hanyu shih-kao•-- For a lenghty discussion of this problem.

73 It is impossible to progress at any length on the problem of syntactical transgressions allowed by 'parallelism' without making a hiatus on the discussion of the lь-shih. For those who read Chinese we strongly recommend the relevant sections of Wang Li's Han-yь shih-lь hsьeh. The following is a very succint explanation of the three typologies in which can be classified the T'ang poets' researches struggling to invent other ordres verbaux (verbal sequences).

1. Ordre Perceptif (Perceptive Sequence):

The poet organises words not according to the usual syntax but in a sequence which attempts to be the explicit reflection of his succession of perceptive images (of a landscape, a sensation, etc.). The following verses are an example of an excursion by the poet Tu Shen-yen· to the southern shore of the mouth of the Yang-tze River, at dawn. The sequence of the words suggests the images gradually seen by the poet as he moves along: images of the rising sun, and of vegetation which turning colours announces the passing a seasonal transition - on both sides of the river:

雲霞出海曙 Yunxia chu haishu

梅柳渡春江 Meiliu du chunjiang

"Nuages lumiиre apparaоtre mer aurore

Pruniers saules franchir fleuve printemps "

("Clouds light appears sea dawn

Plum trees willow trees cross river spring")

Without any previous warning, sometimes the poet selects a striking image as his starting point in the phrase: a scenario, a colour, a flavour which 'provokes' sensations and rememberances - as if all erupts from this striking image. The following examples are from different poems by Tu Fu:

1.1. 寺憶曾游處 Si yi ceng you chu

橋憐再度時 Qiao lian zai du shi

"Temple se rappeler jadis visiter lieu

Pont aimer а nouveau traverser moment"

("Temple remember long ago visit place

Bridge love again go across moment")

1.2. 青惜峰巒過 Qing xi fengluan guo

黃知橘柚來 Huang zhi juyou lai

"Vert regretter monts et collines dйpasser

Jaune pressentir forкt d'orangers approcher"

("Green regret mountains and hills go beyond Yellow foresense forest of orange trees come close")

1.3. 滑憶彫胡飯 hua yi diaohu fan

香聞錦帶羹 xiang wen jindai geng

"Veloutй savourer riz aux champignons "torsadйs"

Parfum humer soupe aux herbes "brodйes""

("Velvety taste "spiralling" mushrooms' rice

Perfume inhale "embroidered" herb soup")

In other cases what the poet attempts to establish is a still condition rather than a succession of images:

白花簷外朵 Baihua yanwai duo

青柳檻前梢 Qingliu kanqian shao

" Saules tendres branches

branches

Fleurs blanches calices"

calices"

("Gentle willows  branches

branches

White flowers  calixes")

calixes")

In these two verses the elements outside the box [before and after]  constitute discontinued signifiers. Between them, the poet integrates the images of "doorstep" and the "canopy" in order to visually define the intrusion of human presence in Nature (or inversely, the invasion of the human 'territory' by Nature). Through a deliberate placing of words the poet reconstitutes a situation as it is actually seen by him.

constitute discontinued signifiers. Between them, the poet integrates the images of "doorstep" and the "canopy" in order to visually define the intrusion of human presence in Nature (or inversely, the invasion of the human 'territory' by Nature). Through a deliberate placing of words the poet reconstitutes a situation as it is actually seen by him.

2. Ordre inversй (Inverted Sequence):

Here, the sequence is built by inverting, in one phrase, the subject and the object. More than the immediate achievement of a figure of style, one can sense in this procedure • the desire to disturb the order of the world and to create a further relationship between things.

香稻啄餘鸚鵡粒 Xiangdao zhuoyu yingwu li

碧桐棲老鳳凰枝 Nitong qilao fenghuang zhi

"Riz parfumй picoter finir perroquet graines

Platane vert percher vieilli phйnix branches "

("Rice perfumed peck finish parrot seeds

Green banana tree perch aged phoenix branches")

Reading this very famous distich by Tu Fu, the reader rapidly understands that it is not the "rice" that "pecks" the "parrot" nor is the "banana tree" that is "perched" on the "phoenix". It should be underlined that, most frequently, poets 'dare' to attempt this type of distortion in 'parallel' verses, as the mutual justification between the verses removes what might seem to be 'fortuitous' or 'arbitrary'.

客病留因藥 Kebing liu yin hua

春深買爲花 Chunshen mai wei hua

"Voyageur malade conserver en raison des mйdicaments,

Printemps tardif acheter а cause des fleurs"

("Ill traveller preserve due to medicaments,

"Late spring buy because of flowers")

The verses mean: "Being frequently ill in my exile, I conserve the medicaments; I buy flowers in an attempt to arrest the passing of spring". The inversion of the subject and the object gives to the verses a disillusioned nuance laced with humour.

永憶江湖歸白髪 Yongyi jianghu gui baifa

欲迴天地入扁舟 Yuhui tiandi ru bianzhou

"Longtemps regretter fleuve-lac retourner cheveux blancs

Toujours errer ciel-terre pйnйtrer barque lйgиre"

("For a long time regret river-lake turn white hair Always wander Heaven-Earth penetrate light boat")

Instead of the "white hair" (exiled) images which are 'scattered' between a "river" and a "lake", and the "light boat" lost between "Heaven" and "Earth", the poet Li Shang-yin, through an inversion procedure, strongly defines the action of Nature over mankind.

3. Ordre dйsagrйgй (Desaggregated Sequence)

In this type of sequence the poet attempts to create a 'total' image by mixing 'cause' and 'effect' in an apparently arbitrary way, and where all elements are confused or anihilated as if in a priviliged manner. Each dynamic phrase where a sign is part of a network in incessant transformation, acquires a new meaning after each change.

地侵山影掃 Di qin shanying sao

葉帶露痕畫 Ye dai luhen hua

"Terrain pйnйtrer montagne ombre balayer

Feuilles entacher rosйe traces inscrire "

("Land penetrate mountain shadow sweep

Leaves spots dew traces inscribe")

In order to give meaning to these verses by Chia Tao·, we provoke a chained transformation to the first verse:

Land penetrate mountain shadow sweep →

Penetrate mountain shadow sweep land →

Mountain shadow sweep land penetrate →

Shadow sweep land penetrate mountain →

Sweep land penetrate mountain shadow →

The moral tone of the last phrase throws light on what the poet attempts to convey: "sweeping" the "land" in front of his abode he "penetrates" onto the "shadow" projected by the "mountain". Applying the same procedure to the second verse, we will arrive at:

Inscribe leaves spots dew traces

The poet "inscribes" verses of "leaves" (of a banana tree, probably) all "spoted" with "dew". In the same spirit, in an attempt to describe a landscape ["green"] where a strong "wind" destroys ["break"] tender "bamboo" shoots drooping ("hanging") their leaves and where drenched "prunus" tree flowers "blossom", their pink ["red"] petals (and we draw attention to the erotic connotation of the situation), Tu Fu changes the 'natural' sequence of the words in order to destroy all connotations with 'past' and 'future', thus establishing an immediate and total image:

綠垂風折筍 Lь chui feng zhe sun

紅綻雨肥梅 Hong zhan yu fei mei

"Vert suspendre vent se casser bambous

Rouge йclater pluie s 'йpanouir prunus "

("Green hanging wind break bamboos

Red burst rain blossom prunus")

74 [See: Part. II, p.186].

See: Note 66.

75 [See: Part. II, p.195].

See: Notes 53 and 95.

76 [See: Part. II, p.168].

TS'UI HAO 崔顥

黃鶴樓

昔人已乘黃鶴去

此地空餘黃鶴樓

黃鶴一去不復返

白雲千載空悠悠

晴川歷歷漢陽樹

芳草萋萋鸚鵡洲

日暮鄉關何處是

煙波江上使人愁

Le pavillon de la Grue jaune

Les Ancients dйjа chevauchant / Grue Jaune partir

Ce lieu en vain rester / pavillon de la Grue Jaune

Grue Jaune une fois partie / ne plus revenir

Nuages blancs mille annйes / planer lointain-lointain

Fleuve ensoleillй distinct-distinct / arbres de Han-yang

Herbe parfumйe, foisonnante-foisonnante / Ile des Perroquets

Soleil couchant pays natal/oщ donc est-ce

Vagues brumeuses sur le fleuve / accabler de tristesse homme

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 168.

The Yellow Crane Hall

The sage, astride the Yellow Crane, flew away.

A singular void, the whole place now betray.

The Yellow Crane has, for certain, gone for good.

White clouds have long o'espread the Hall, like a hood.

This fine weather, trees in Hanyang can be seen.

Grass on Parrot Isle is growing rank and green.

Where is my hometown at this approach of eve!

At the mist o'er the stream, I cannot but grieve.

In: Xu Zhongjie, trans., ed., 200 Chinese Tang Poems in English Verse, Beijing, Beijing Languages College Publishers, 1990, p.51.

77 [See: Part. II, pp.226-227].

TU FU 杜甫

石壕吏

暮投石壕村

有吏夜捉人

老翁踰 走

老婦出門看

吏呼一何怒

婦啼一何苦

聼婦前致詞

三男鄴城戍

一男附書至

二男新戰死

存者且偷生

死者長已矣

室中更無人

惟有乳下孫

有孫母未去

出入無完裙

老嫗力雖衰

請從吏夜歸

急應河陽役

猶得備晨炊

夜久語聲絕

如聞泣幽咽

天明登前途

獨與老翁别

Le recruteur de Shih-hao

Je passe la nuit au village de Shih-hao.

Un recruteur vient s'emparer des gens.

Escaladant le mur, le vieillard s'enfuit,

Sa vieille femme va ouvrir la porte:

Cris d'officier, colйreux,

Pleurs de femme, amers.

Elle parle enfin. Je prкte l'oreille:

"Mes trois fils sont partis pour Yeh-ch'eng.

L'un d'eux а pu envoyer un message:

Les deus autres sont morts au combat.

Le survivant tentera de survivre,

Les morts sont morts, hйlas, pour toujours!

Dans la maison, il n'y а plus personne,

A part le petit qu'on allaite encore.

C'est pour lui que sa mиre est restйe:

Pas une jupe entiиre pour sortir!

Moi, je suis vieille, j'ai l'air faible,

Mais je demande de vous suivre

A la corvйe de Ho-yang. Dйjа

Je peux faire le repas du matin."

Au milieu de la nuit, les bruits cessent

On entend comme un sanglot cachй...

Le jour pointe, je reprends ma route:

Au vieillard, seul, j'ai pu dire adieu.

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, pp.226-227.

The Conscription Officer at Shih-hao

It was late, but out in the night

when I arrived, he was collaring men.

Her husband, the old inn-keeper, slipped

over the wall, and she went to the gate.

The officer cursed loud and long, lost in

his rage. And lost in grief, an old woman

palsied with tears, she began offering

regrets: My three sons left for Yeh.

Then finally, from one, a letter arrived

full of news: two dead now. Living

a stolen life, my last son can't last,

and those dead now are forever dead and

gone. Not a man left, only my little

grandson still at his mother's breast.

Coming ang going, hardly half a remnant

skirt to put on, she can't leave him

yet. I'm old and weak, but I could hurry

to Ho-yang with you tonight. If you 'd

let me, I could be there in time,

cook an early meal for our brave boys.

Later, in the long night, voices fade.

I almost hear crying hush - silence...

And morning, come bearing my farewells,

I find no one but the old man to leave.

In: HINTON, David, The selected poems of Tu Fu, New York, New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1989, pp.36-37.

78 We use the terms 'metaphors' and 'symbolic imagery' in a general sense. (See the examples given in the following paragraph). The intention is not to extricate isolated figurations but to analyse how images successively unfold and what is the working system of the language derived from this succession.

79 [See: Part II, p.185].

TU FU 杜甫

月夜

今夜鄜州月

閨中只獨看

遥憐小兒女

未解憶長安

香霧雲鬟濕

清輝玉臂寒

何時倚虚幌

雙照淚痕乾

Nuit de lune

Cette nuit / lune sur Fu-chou

Dans le gynйcйe / seule а regarder

De loin chйrir / petits fils-filles

Non encore capables de / se rapeller Longue-paix

Brume parfumйe / chignon de nuage mouiller

Clartй pure /bras de jade fraоchir

Quel moment / s'appuyer contre rideau

Йclairer а deux / traces de larmes sйcher

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.185.

Moonlit night

To-night Fu-chou moon

My-wife can-only alone watch

distant sorry-for little sons-daughters

Not-yet understand remember Ch'ang-an

Fragant mist cloud-hair wet

Clear light jade-arms cold

What-time lean empty curtain

Double-shine tear-marks dry

In: HAWKES, David, A Little Primer of Tu Fu, Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong-The Oxford University Press, 1994, pp.31-32.

80朱門酒肉臭,路有凍死骨 Zhumen jiurou chou, luyou dongsi gu (Tu Fu: Tsu ching fu Feng-hsien-hsien yong-huai wu-pai tsu).

In these two verses the images of "red doors" and "winemeat" are to be taken as synecdoches while that of "roads" is to be assimilated to a metonym. But... once again, we would like to make it clear that we are concerned in classifying matters.

81[See: Part. II, p.192].

TU FU 杜甫

春夜喜雨

好雨知時詳

當春乃發生

隨風潛入夜

潤物細無聲

野徑雲俱黑

江船火獨明

曉看紅濕處

花重錦官城

Bonne pluie, une nuit de printemps

Bonne pluie /connaоtre saison propice

Au printemps /alors favoriser vie

Suivre vent/furtive pйnйtrer nuit

Humecter objects/dйlicate sans bruit

Sentiers sauvages / nuages tout noirs

Barque fluviale /fanal seul lumineux

А l'aube regarder/ endroit rouge mouillй

Fleurs alourdies / Mandarin-en-robe-de-brocart

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.192.

Spring Night, Delighted by Rain

Lovely rains, knowing their season,

Always appear in spring. Entering night

Secretly on the wind, they silently

Bless things with such delicate abundance.

Clouds fill country lanes with darkness,

The one light a riverboat lamp. Then

Dawn's view opens: all bathed reds, our

Blossom-laden City of Brocade Officers.

In: HINTON, David, The selected poems of Tu Fu, New York, New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1989, p.61.

82 [See: Part. II, p.185].

See: Note 79.

83 [See: Part. II, pp.186-187].

See: Note 66.

84 See: Anthologie de la poйsie chinoise classique - for a [French] translation of this long poem.

85 襄王雲雨今何在,江水東流猿夜啼 Xiangwang yunyu jin hezai, jiangshui dongliu yuan yeti (Li Po: Hs iang-yang ke·).

86 [See: Part. II, p.153].

TU MU 杜牧

遣懷

落魄江南載酒行

楚腰腸斷掌中輕

十年一覺揚州夢

赢得青樓薄倖名

Aveu

Ame sombrйe fleuve-lac / portant vin balader

Taille de Ch'u entrailles brisйes / corps lйger dans la paume

Dix annйes un sommeil / rкve de Yang-chou

Gagner parmi les pavillons-verts / renom de l'homme sans cœur

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.153.

In Idle Meditation

Down and out I wander over the waters with a supply of wine,

The girls here are like the wasp-waisted beauties of Ch'u,

So light that they could dance on the palm of one's hand.

For ten years I have lived besotted in Yang Chou,

And now all that I have to show for it is the reputation for a night-of-love in the houses of ill fame.

In: JENYNS, Soame, trans., Selections from the Three Hundred Poems of the T'ang Dynasty, London, John Murray, 1940, pp.44-45.

87 誰驚一行雁,衝斷過江雲 Shui jing yi hang yan, chong duan guo jiang yun (Tu Mu: Chiang lou·).

88 [See: Part. II. p.125].

WANG CH'ANG-LING 王昌齡

宮怨

閨中少婦不知愁

春日凝妝上翠樓

忽見陌頭楊柳色

悔教夫婿覓封侯

Complainte du palais

Dans le gynйcйe jeune femme / ne pas connaоtre chagrin

Jour printanier se parer / monter йtage en bleu

Soudain apercevoir sur le chemin /couleur de saules

Regretter avoir laissй йpoux / chercher titre nobiliaire

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p. 125.

Grief in the Ladies' Apartments

In the women's apartments is a young woman who does not know sorrow.

On a spring day she paints her face and goes up to the kingfisher tower.

Suddenly she notices the willow buds are bursting along the paths

And she regrets she has sent away her husband in search of military glory.

In: JENYNS, Soame, trans., Selections from the Three Hundred Poems of the T'ang Dynasty, London, John Murray, 1940, p.46.

89 IV-VI centuries BC [220-589BC].

90 The meaning is indeed quite vast, comprising, for instance the "mйtaphores filйes " ("knitted metaphors") defined by M. Riffaterre.

91 There are several English translations of this poem, notably that by J. D. Frodsham [not available].

[See: Part. II, p.242].

LI HO 李賀

李慿箜篌引

吳絲蜀桐張高秋

空白凝雲颓不流

江娥啼竹素女愁

李憑中國彈箜篌

崑山玉碎鳳凰叫

芙蓉泣露香蘭笑

十二門前融冷光

二十三絲動紫皇

女媧煉石補天處

石破天驚逗秋雨

夢入神山叫神嫗

老魚跳波瘦蛟舞

吳質不眠倚桂樹

露腳斜飛濕寒兔

Le k'ung-hou

Soie de Wu platane de Shu /dresser automne haut

Ciel vide nuages figйs / choyant et ne coulant plus

Dйesse du fleuve pleurer bamboos /Fille Blanche se lamenter

Li P'ing au Milieu du Pays / pincer le k'ung-hou

Mont K'un-lunn jades se briser / couple de phoenix s'interpeller

Fleurs de lotus verser rosйes / orchidйes parfumйes rire Douze portiques par devant / fondre lumiиres froides Vingt-trois cordes de soie /йmouvoir Empereur-Pourpre Nь-wa transformant rochers / rйparer voыte cйleste Pierres fendues ciel йclatй /ramener pluie automnale Rкvant pйnйtrer Mont Magique / initier la chamane Poissons vieillis soulever vagues / long dragon danser Wu Chih hors du sommeil /s'appuyer contre cannelier Rosйes ailйes obliquement s'envolant / mouiller liиvre frissonant

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise / suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.242.

Li P'ing on the K'ung-hou Harp

Wu silk, Shu paulownia wood, streching high Autumn;

Sky white, congealed clouds crumbling, not floating;

The Ladies of the River Hsiang shedding tears on the bamboo, the White-silk Girl sorrowful;

Li P'ing playing the k'ung-hou harp in the capital of China.

Mount K'un-lun jade shatters, phoenixes scream,

Lotuses weep dew, fragant orchids smile.

In front of the twelve city gates the cold light melts;

Twenty-three strings move the Purple Emperor.

Where the goddess Nь Wa with smelted stones mended the sky,

Stones break, and the sky astonished, induces the Autumn rains.

In dreams, entering the Mythic Mountains to teach the Mythic Sorceress;

Aged fish leap the waves, scraggy dragons dance.

Wu Kang, sleepless, leans on the cassia tree;

A trail of dew flies aslant, wets the shivering hare.

In: TU, Kuo-ch'ing, Li Ho, Boston, Twayne Publishers, 1979, pp.76-77.

92 [See: Part II, pp.201 (poem and commentary), 204].

LI SHAN-YIN 李商隱

錦瑟

錦瑟無端五十絃

一絃一柱思華年

莊生曉夢迷蝴蝶

望帝春心託杜鵑

滄海月明珠不淚

桑田日暖玉生煙

此情可待成追憶

只是當時已惘然

Cithare ornйe de brocart

Cithare ornйe pur hasard / voici cinquante cordes

Chaque corde chaque chevalet / dйsirer annйes fleuries

Lettrй Chuang rкve matinal / s'illusioner papillon

Empereur Wang cњur printanier / se confier tu-chьan

Mer sans fond lune claire/perles avoir larmes

Champ Bleu soleil ardent/jades naоtre fumйe

Cette passion pouvant durer / devenir poursuite-souvenir

Seulement au moment mкme / dйjа dй-possйdй

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise/ suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.204.

The patterned lute

Mere chance that the patterned lute has fifty strings.

String and fret, one by one, recall the blossoming years.

Chuang-tzu dreams at sunrise that a butterfly lost its way,

Wang-ti bequeathed his spring passion to the nightjar.

The moon is full on the vast sea, a tear on the pearl.

On Blue Mountain the sun warms, a smoke issues from the jade.

Did it wait, this mood, to mature with hindsight?

In a trance from the beginning, then as now.

In: GRAHAM, A. C., trans. and intro., Poems of the Late T'ang, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1965, 171.

For the use of metaphors in Li Shang-yi it is also interesting to read the poem (Sans titre) Untitled with our respective commentaries.

LI SHAN-YIN 李商隱

無題

相見時難别亦難

東風無力百花殘

春蠶到死絲方盡

蠟炬成灰淚始乾

曉鏡但愁雲鬢改

夜吟應覺月光寒

蓬萊此去無多路

青鳥殷勤爲探看

Sans titre

Se voir bien difficile /se sйparer davantage

Vent d'est perdre force / cent fleurs faner

Vers а soie jusqu' а la mort/soies alors йpuiser

Flamme de bougie devenir cendres / larmes seulement sйcher

Miroir du matin s 'attrister/chignon de nuage changer

Chant de nuit ressentir / clartй lunaire froidir

Mont P'eng d'ici aller / sans aucun chemin

Oiseau Vert sans relвche /pour surveiller

In: CHENG, Franзois, l'йcriture poйtique Chinoise /suivi d'une anthologie des poиmes des T'ang, Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1982, p.200.

Untitled poems (vi)

For ever hard to meet, and as hard to part.

Each flower spoils the failing East wind.

Spring's silkworms wind till death their heart's threads:

The wick of the candle turns to ash before its tears dry.

Morning mirror's only care, a change at her cloudy temples:

Saying over a poem in the night, does she sense the chill in the moonbeams?

Not far from here to Fairy Hill.

Bluebird [sic], be quick now, spy me out the road.

In: GRAHAM, A. C., trans. and intro., Poems of the Late T'ang, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books (Classics), 1965, p. 150.

* Translator's note: this commentary is addressed to the author's French translation of the poem supporting his discourse in the main text, and not to the above English translation. See: III, p. 60

The Green Bird. [sic]The messenger of Hsi-wang-mu· (the Queen Mother of the West, daughter of the Celestial Sovereign and master of all sun setting lands).

In a series of poems of extremely allusive mood Li Shan-yin sang of the secret loves held by him with a court lady or with a Taoist nun. In this poem written in a 'spoken style' (except the first verse) unfolds a love theme (love and a parting drama) in a network of images and metaphors frequently based in phonal connections. In the third verse ts'an· ("silkworm") is homonymous [sic]with the expression ts'an mien ('amorous links', 'amorous encounters'), while ssu· ("silk" "threads") is homonymous with the word ssu· ('[amorous] thoughts', 'desire'). Also 'silk thread' is part of ch'ing ssu· ('green threads') which also means 'black hair' from which derives the image of "chignon" in the fifth verse. In the fourth verse hui· ("ashes") is part of the expression hsin-hui· ('broken heart') which prolongs the idea of a frustrated love, explicated in the previous verses. Furthermore hui· also stands for the colour 'gray', which is related to the image of the hair ["chignon"] colour "change" in the fifth verse. Once again in the fourth verse, the image of the "flame of candle" refers to both the image of the "wind" in the second verse, and to the image of the "brightness [of the] moon" in the sixth verse. At another level, the image of the "moon" brings to mind the identity of the solitary Goddess Ch'ang O which, in turn, recalls the thought of the distant lover and the eventuality of both lovers being forever reunited beyond death, in a land of bliss and eternal fulfillment.

The poem is thus transformed in a drama by the ensemble of images and metaphors which maintain in reciprocity the essential connections. The verses are not to be read as a descriptive narrative but to be savoured as a 'tragic performance'. In the second verse the images of the "wind" and "flowers" make allusion to a frustrated love at the same time suggesting the realization of the sexual act. The parallelism of the third and fourth verses continue this idea of the sexual copulation ("silkworms" and "candle") veiled under the theme of an 'oath of fidelity'. The fifth and sixth verses narrate the lovers separation subtly implying that the destiny of the lovers is that of Nature itself, a Nature in constant transfiguration. Moreover, this transformation is the essential condition which makes dreaming a reality. Unfolding through a series of phases indestructible by the passing of time, the poem opens up to infinity. See: Note 92.

93 滄海桑田 Canghai sangtian

94 Our translation and analysis are not meant to wrongly convey that the poem is nothing other but a conglomeration of images. It is in fact a tune where the absence of words expressing feelings is accentuated by the poignancy of the musicality. To a Chinese ear the verses are not less melodious than, for instance, the deliverance of Ariel in Shakespeare's The Tempest: "Full fathom five thy father lies / Of his bones are coral made / Those are pearls that were his eyes / Nothing of him that doth fade / But doth suffer a sea-change / Into something rich and strange / [...]", or less 'telling' that in Maurice Scиve complaints: "En moy je vis, oщ que tu sois absente, /En moy je meurs, oщ que soye present. / Tant loing sois tu, toujours tu es present,/Pour pres que soye, encore suis je absent/[...]."

95 [See: Part. II, p.132].

See: Note 62.

* Lecturer at the Institut National de Langues et Civilisations Orientales, Universitй de Paris III, (National Institutes for Oriental Languages and Civilizations, University of Paris III), Paris.

*** Qi Bu Shi, · meaning 'Seven-Step Poem'. The story goes that Cao Zhi· was forced to compose a poem with a limit limit set by his power-thirsty brother Cao Pei, · who was jaelous of poet's literary gift and achievement and thus bent on finding an excuse to kill him. Cao Zhi wrote this poem while walking and just finished it at the count-down of seven steps.

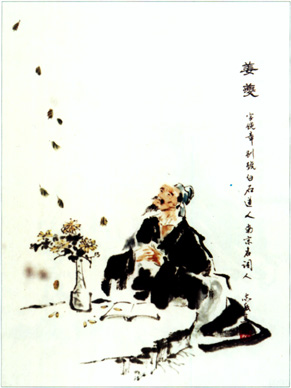

SA DUCI薩都刺(°1308- †13??)

Aliases: Tian Shi天賜, Zhizhai 直齋.

LEI CHI NGOK 李志岳LI ZHIYUE

1995. Colour inks on rice paper. 23.0 cm x 33.0 cm.

§1.

Signs engraved in tortoise bones and buffalo's scapulae. Signs which sacred vases and bronze utensils carry on their flanks. 1 Divinatory or utilitarian, they manifest themselves as traceries, emblems, immovable manners, visualized rhythms. Regardless of its utterance, constituting a unity by itself, each sign has the potential to remain sovereign, and thus to become everlasting. So, since its origins, it has been a writing that refuses to be a mere support of oral language: its development has been a long struggle aimed at achieving autonomy as well freedom of arrangement. Ever since its origin it has stood up to this contradictory and dialectical relationship between the pronounced sounds and the physical presence, with a tendency towards gestures, between the exigency of linearity and the desire of a spatial evasion. Can it be said that this is 'crazy defiance' from the Chinese to maintain as such this 'contradiction', for about forty centuries?

What cannot be denied is that it was a most extraordinary adventure, thus enabling it to be said that through their writing the Chinese accepted a challenge, a unique challenge, which came to be the great benefice of the poets.

Thanks to this writing, in effect since slightly longer than three-thousand years ago, an uninterrupted melody was passed on to us.2 This melody that, at its inception, was intimately connected with sacred dance and with agrarian field work regulated by seasonal rhythms, came to eventually suffer considerable metamorphoses. One the elements which determined the origin of these metamorphoses was exactly this writing which has developed into an extremely original poetical language. All T'ang poetry is a written melody as well musical writing. Through these signs, complying with a primordial rhythm, a word has exploded and expanded beyond and from everywhere its signifier's act. First of all to define the reality of these signs, the Chinese ideograms, their specific nature, their connections with other significant practices (such are the intentions of this article) it is essential to explain certain facets of Chinese poetry.

It is usual when speaking of Chinese characters to evoke their imagistic representations. Those who are ignorant of this writing easily take it as an aggregate of 'small squiggles'. It is true that in its oldest known configuration, it is possible to pick out an important number of pictograms such as the 'sun' (⊙, then stylized as 日), the 'moon' ( , then stylized in 月), and 'man'/'homo' (

, then stylized in 月), and 'man'/'homo' ( , then stylized in 人); but also next to them are represented characters more abstract which can already be qualified as ideograms, such as 'king' (王: that which connects the 'sky', the 'earth' and 'mankind'), 'centre' (中: a space crossed by a line at the centre), and 'to return' (

, then stylized in 人); but also next to them are represented characters more abstract which can already be qualified as ideograms, such as 'king' (王: that which connects the 'sky', the 'earth' and 'mankind'), 'centre' (中: a space crossed by a line at the centre), and 'to return' ( , stylized in 反: a hand describing a turning gesture towards oneself). From a limited number of simple characters later arose the complex characters: those are the ones which constitute most of the Chinese ideograms which are currently in use. A complex character is a compound of two simple characters; thus the word 'clarity'明 is formed by the 'sun' and the 'moon'. But the common example of a complex character is that of the type 'radical + phonetic sign', that is, a radical made of a simple character (equally named 'key', because it is the radical which determines the category to which belongs the word; being the compound of all Chinese words subdivided into two hundred and fourteen types, that two hundred and fourteen 'keys': the 'water' 'key', the 'wood' 'key', the 'man' 'key', etc.) and of another section equally made by a simple character which acts as a phonetic sign: this one by its own pronunciation, gives the pronunciation to the word (that is, the simple character acting as a phonetic sign and the complex character which is also its constituent have the same pronunciation). Let us cite, for instance, the word 'companion'·伴 which is a complex character, It is formed by a 'key', the 'man' 'key' 亻, and of another simple character 半 which is pronounced pan· and which indicates that the complex character 'companion' is also pronounced pan. (This obviously gave rise to numerous homonymous cases of which we will later explain the implications). It must be noted that the choice of a simple character which therefore does not have other function than that of being a phonetic sign is not always gratuitous. Of the example we just mentioned, the simple character pan 半 means 'half '· which combined with the 'key' for 'man' evoke the idea of 'another half' or of 'the man who shares' thus contributing to underline the precise meaning of the complex character 伴· which is its 'companion'. This example make us notice an important factor: if the simple characters whose function is to act as 'self-signifiers' work by their gestural and emblematic looks, in this case, even if it is a purely phonal audible element, one still strives to link it to a meaning. To suppress the gratuitous and the arbitrary at all levels of a semiotic system founded on an intimate relationship with reality, in such a way as to prevent all future ruptures between signs and the world and thus between mankind and the universe: this always seems to have been the tendency of the Chinese. This suggestion enables us to proceed further into the reflection on the specific nature of the ideograms.