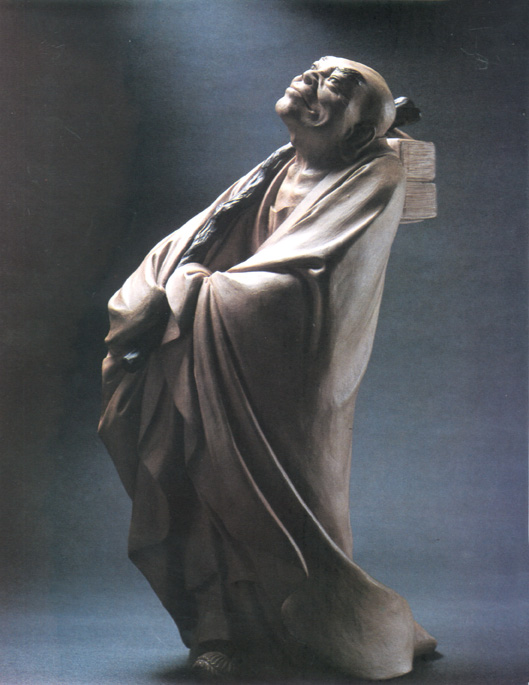

Lo Han,the Saint Fired Clay 28cm high (Shek Wan)

Lo Han,the Saint Fired Clay 28cm high (Shek Wan)

The Leal Senado of Macau held two exhibitions of Portuguese Pottery, one of XIX Century Portuguese Pottery and the other of Contemporary Portuguese Pottery, in the Luís de Camões Museum between the 20th of March and the 6th of May to "continue the dynamic intercultural relationship which has existed for so many years and to disseminate information on the cultures represented in the territory as well as to encourage mutual understanding between Portugal and the People's Republic of China" (António Conceição Júnior, Exhibition Catalogue, Introduction).

In view of the fact that there is a surprising similarity between the ceramic styles of Caldas da Rainha and Shek Wan to the extent that even the manufacturing process is similar, the question then arises of whether the two "schools" influenced each other and, if so, how?

I shall not attempt to answer the above question in this short article for there is but scanty evidence to do so. I intend to do no more than offer the reader a description of the first stages in the evolution of pottery, in particular Chinese pottery, the invention of porcelain, developments in manufacturing, the perfecting of these techniques and the subsequent dissemination throughout Europe which was initiated by the Portuguese who took it to Portugal in their ships.

THE INVENTION OF POTTERY

None of the opinions on the origins of pottery is anything more than pure conjecture. It may be the case that Man, having watched the effect of fire when it came into contact with wet earth, tried to "cook" some kind of dampened earth, Maybe he dried clay in the sun, perhaps as adobe, and made some objects impermeable by smearing them with fatty materials.

Others explain the origins of pottery as the "proofing" of rush objects by coating them with mud and drying them in the sun.

After repeated experiments, Man produced the first kitchen objects as a substitute for stone which was heavy, hard and impractical. The first kilns must have been buried in the ground just as the ones which are used nowadays for firing earthenware.

Chance, want and necessity all played a part in Man achieving the paste which would be used to mould the first receptacles: a flattened paste which was possibly used to construct the first habitations.

Gourd-shaped bottle

Decorated in high relief with a lizard

curved round the belly. White glass dyed

with indigo, lizard in green and brown.

Hgt: 340mm

Cat: MC 116.

Mark: M. G. Bordalo Pinheiro, 1906.

Workshop: Fábr, Bordalo Pinheiro, 1907.

Gourd-shaped bottle

Decorated in high relief with a lizard

curved round the belly. White glass dyed

with indigo, lizard in green and brown.

Hgt: 340mm

Cat: MC 116.

Mark: M. G. Bordalo Pinheiro, 1906.

Workshop: Fábr, Bordalo Pinheiro, 1907.

Whatever its origins, the invention of pottery is definitely one of Man's greatest cultural achievements and the manufacture of bowls, jars, tea-cups and clay pots must be regarded as the beginning of science for the potter has to make a precise calculation as to the proportions of the various substances to be mixed with the clay and the temperature at which the objects must be fired to make them resistent and waterproof without exploding.

In China, the start of pottery as an industry began in the third millenium B.C. with the production of cooking receptacles, cups for wine, and later sacrificial urns. The emperors were linked to the progress of this industry right from the very beginning. Huang-ti, the semi-legendary Yellow Emperor, appointed the potter Kun-Wu as "pottery superintendent". Yu Ti Shuen, regarded by the Chinese as a "great and good emperor" held pottery in high regard and the emperor Shun himself made objects from clay in Hopin before ascending the throne.

It is thanks to the support of successive emperors that Chinese pottery was able to develop so extraordinarily, attaining a peak of perfection in the Zhou Dynasty (1122 - 225 B.C.) The oldest known pieces have been found in graves. With the aid of archeaological techniques we now know that in the Zhou Dynasty the Chinese placed three clay receptacles containing meat preserved in brine, dried meat and sliced meat respectively, two glasses of wine and other alcoholic drinks as well as clothes, weapons, mirrors and jade objects in the graves of the dead. It is thanks to the "pottery of the dead" that we can now reconstruct the evolution of pottery.

Nowhere in the world are the dead abandoned. Even when they are thrown into the sea, there is an overriding belief in their survival: this is the return to the waters of the uterus, the first experience of the maternal womb, the waters of rebirth in which all the secrets of life are held. In the case of throwing the body into the sea, other objects which the deceased would need in the next world were also thrown in. All practices related to the burial of the dead, whether at sea or on land, are witness to a belief in their survival in an afterlife identical to that which they had on land.

For the Chinese, life in the next world was a continuation of life on earth. In Paradise, the deceased experienced the same desires and same needs as during life on earth: eating, dressing, drinking and socialising. As the luck of the living depended on the happiness and comfort of the dead, wooden, bronze or clay models of horses, servants, dancers, cups and pans were placed in the deceased's grave in order to satisfy their needs. Everyday life continued into death along with class distinctions: there were those who ruled and those who obeyed, lords and slaves, rich and poor. The house of the dead man had to be a reflection of the house he had while living. This is why there are models of servants, camels loaded with goods, horses and sumptuously decorated homes in the graves.

The cult of the ancestors made an extraordinary contribution to the manufacture and perfection of pottery. This was true to the extent that in the reign of Emperor Tai Kung (627 - 649 A. D.) competition started up in the production of "furniture" and other objects destined for the graves and the emperor was forced to announce an imperial decree limiting the quantity and size of the items which could be sent to the grave with the body.

Closely linked to the development of pottery, most of all in the industrialization of the craft, is the potter's wheel. The Chinese claim that it was they who invented it.

There is no evidence to prove this claim. It may have been discovered at around the same time in several different parts of the world and in some cases long before China. It is almost definite that Egyptian potters from the Fourth Dynasty (3200 B.C.) used the wheel and it was certainly used for Minoan pottery in Crete dating from 3000 B.C.. Chinese documents from the Zhou Dynasty allow us to conclude that during this period there was a professional distinction between the craftsmen who modelled with clay and those who worked with a wheel.

The ceramic tradition developed gradually over the centuries and as early as the Zhou Dynasty potters were applying a non-porous glaze on clay objects. Objects, such as models of houses, animals and people, partly covered with a greenish-grey glaze have been found in tombs dating from the 3rd century B.C..

The way had been opened for the invention of porcelain.

It is here that there is the greatest difference between Chinese civilization and the other civilizations which preceeded it in Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoa, Jomon. While the latter disappeared, Chinese civilization stretches as far back as the fourth millenium B.C. with an ever-developing artistic tradition which has continued unbroken over the centuries right up to the present.

The 1920 discovery of "Peking Man" (reckoned to be between three hundred thousand and five hundred thousand years old) in a cave heaped with stone tools and burnt bones; the discovery of "LanTien Man" (around six hundred thousand years old), found near Shian in 1963 and 1964; the recent discovery of several specimens of Neanderthal Man in various parts of the People's Republic of China all confirm the belief that Chinese civilization nowadays is the result of a continuous historical process.

PORCELAIN

Just as the case is with pottery, there is no unanimous agreement as to a date for the invention of porcelain. Some European specialists doubt that there was porcelain before the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A. D.) but nobody disputes the fact that it was the Chinese who first produced it.

In Chinese "porcelain" is expressed by the character 瓷 (tzu) which dates from the third century A. D.. but the first pieces of porcelain must have been produced some hundreds of years prior to this, during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. - 220 A. D.) for early porcelain is classified as "Yueh" (formerly Yueh - Chou in Shaoshin) this being the place where a primitive kiln for producing the porcelain was found. Writings of the period note that the pieces were "as translucent as jade" and "as resonant as a musical instrument".

The oldest dictionaries define tzu as "fine, compact pottery", a description which does not concord entirely with the European notion that porcelain must be made from kaolin and feldspar and be translucent.

According to S. Bushell, the Chinese call "any thick, opaque piece tzu, if it gave out a clear, resonant note on percussion, this being the practical test by which they distinguish porcelain". This means that "there is considerable difficulty in distiguishing glazed vases of Chinese pottery from true porcelain". (1)

In Europe it was the Portuguese who coined the word "porcelana" ("porcelain"). In 1516, Edoardo Barbosa returned from a voyage to China and, on explaining the techniques and materials used for making it, he compared it to the cowrie, also called "porcelana" in Portuguese.

Many experiments were needed before porcelain could be produced. The two main substances required to make it are kaolin and pentutse, The word "kaolin" is derived from the name of the mountains where it was discovered, Kao-ling near Ching-Te-Chen. Pentutse is similar to kaolin but the feldspar is less decomposed and it turns into a kind of glass when it is fired.

"Mofina Mendes"

Standing on a rectangular base with

concave corners. Raised arms hold a

hood blown by the wind.

On the base, a broken pot and moss.

Inscription: "Que todo o humano

deleite/como o meu pore de azeite/Há-de

dar contigo em terra" (“That every man

who rejoices/like my pot of oil/shall end in

the soil) Gil Vicente/1534".

Glazed polychrome on a brown base.

Arms and face unglazed.

Hgt: 295 mm.

Cat: MC 278.

Mark: M, G. Bordalo Pinheiro, 1916.

Workshop: Fátbr. Bordalo Pinheiro.

"Mofina Mendes"

Standing on a rectangular base with

concave corners. Raised arms hold a

hood blown by the wind.

On the base, a broken pot and moss.

Inscription: "Que todo o humano

deleite/como o meu pore de azeite/Há-de

dar contigo em terra" (“That every man

who rejoices/like my pot of oil/shall end in

the soil) Gil Vicente/1534".

Glazed polychrome on a brown base.

Arms and face unglazed.

Hgt: 295 mm.

Cat: MC 278.

Mark: M, G. Bordalo Pinheiro, 1916.

Workshop: Fátbr. Bordalo Pinheiro.

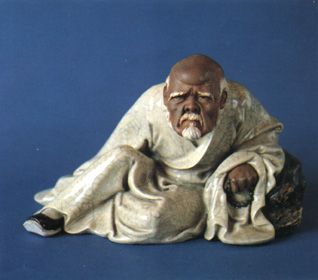

Lo Han with the expression of a lynx

Glazed clay, 1949.

Hgt: 140 mm.

(Shek Wan)

The quantity of each substance had to be carefully measured, dissolved in water with small amounts of other materials and left to settle for a long time as if it were fermenting. Only after this process was the clay kneaded like a dough so as to attain a dense, uniform paste, free from any 'lumps and impurities to prepare it for firing. Otherwise the kiln would destroy the piece which had been so lovingly prepared and created. Before going into the kiln, the objects which had been modelled or turned were left to dry out for a long time and when they were completely dry they were given a coating of glaze and then fired at an extremely high temperature which varied according to size, complexity and decoration. Firing took between thirty six hours and a maximum of twenty days after which the kilns were cooled very slowly.

It is astonishing to think of the level of technical knowledge of resistance, weight, measurements and temperature needed to make the first porcelain objects.

During the Tang Dynasty, the art of porcelain took a great step forward with the help of support from successive emperors. The founder of the dynasty ordered that porcelain should be produced in Chang-nan-chen located on the southern banks of the River Chang. From there it was to be sent to the Capital for the use of the Palace. An Arab writer who visited China in the 9th century described porcelain in the following manner: "There is in China a very fine clay with which they make vases which are transparent as glass; water is seen through them." (2)

In China itself, official reports from the same period describe porcelain objects as being made of fine white clay, the best being of as brilliant and pure a colour as jade, so that they were known as "false jade vessels".

As time went on, Chang-nan-chen became the greatest ceramics centre in China receiving imperial protection from around 1400 up to the Republic (1912). A large number of private kilns were built alongside the imperial kilns.

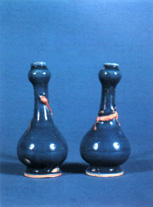

Pottery vase with reptile curved around it

Jia Qing Era (Ming Dynasty)

Jing De Zhen, Jiang Xi Province.

Hgt: 141 mm.

Top diameter: 18 mm.

Base diameter: 46 mm.

(Donated to the Luís de Camões Museum

by China)

Bobbing Figure - "Zé Povinho"

Standing on a semi-spherical base.

Inscription on his stomach: "Taxes".

Glazed polichrome. Hands and face

Unglazed.

Hgt: 245mm.

Cat: MC232.

Workshop: F. F. C. R. 1895.

(Caldas da Rainha)

The porcelain was taken by boat from Chang-nan-chen to Lake Po-Yang and then along the River Yang-tzi as far as Kinkiang. From this port the goods were distributed to all the regions of the huge Middle Empire. Nevertheless,some porcelain was produced for the exclusive use of the emperor and this was packed and sent to the capital along the Grand Canal.

Porcelain was also produced for export. Some of it reached countries in the Middle East by the two silk routes (Canton - Ceylon -the Persian Gulf or the Tartar route via Mongolia - the Caspian Sea - Poland). 14th and 15th century pieces have been found in the Persian Sanctuary in Ardebil, Topkapu Serai (Istanbul).

While the Chinese were developing porcelain production, other peoples (the Arabs, Byzantines, Persians) were perfecting the manufacture of faience.

After the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, the Arabs perfected their techniques for producing colourful, translucent, glazed faience, and decorative "azulejos" which were predominantly used in palaces and temples.

PORCELAIN FOR EUROPE

Portuguese traders were the first people to introduce Chinese porcelain into Europe. The Chinese produced the first pieces of blue and white porcelain for them, the most famous being a vase decorated with the armillary sphere, King Manuel's coat of arms. The finest porcelain was first bought in Neng-Po for a very small price. Some of it was sent to Japan together with cargoes of silks and it was sold in exchange for silver.

The remainder of the porcelain was taken to Lisbon which at this time was the "warehouse of all the marvels to come from the Orient", What space in the Rua Nova and the Rua dos Ferros which was not taken up with goldsmiths and jewellers was "crowded with sumptuous establishments selling books, porcelain, velvet, silks and many other articles mainly from Japan and China". (3)

After the massacre of all the Christians in Neng-Po in 1545, the Portuguese who managed to escape from there searched for a spot further south, coming ashore on Lampacow and Sanchow Islands where they did business with the coastal traders until they finally settled on Amacao (Macau) in 1553.

The porcelain destined for Lisbon left from Macau in carracks. From Lisbon it was then sent on to other European countries where it was known as "carrack ware" in virtue of the means of transportation.

Meanwhile, the Dutch had decided to trade directly with China and they began to attack Portuguese possessions and ships, The carrack Santa Catarina, carrying an almost full cargo of porcelain was taken prisoner and sold in Amsterdam. So, little by little, Europe was inundated with porcelain not only from Portuguese ships but also from the Dutch and English who had formed the East India Company in 1559 although they only arrived in China in 1631.

In the 18th century, the Chinese began to produce pieces with European designs such as palaces, court scenes, coats of arms, landscapes and dancers. Their techniques were so highly developed that they could imitate and faithfully reproduce anything they were shown even though they had no idea of its significance. An example of this were the religious scenes which the Jesuit missionaries gave them, namely, scenes of the crucifiction, Jesus' ascent to Heaven, the Virgin Mary and the Apostles (the famous "Jesuit porcelain").

In the meantime, France and Germany managed to produce the first pieces of porcelain at the beginning of the 18th century. By the second half of this century factories in these countries and also England were producing porcelain on a major scale. As from 1780, exportation of Chinese porcelain to Europe declined because the market was saturated with goods from the European and particularly the English factories.

Why were the Portuguese not the first to produce porcelain in Europe when they had been the first to discover and commercialize it; when they had held the secret to the raw materials, the techniques for glazing and firing it; when, in 1569, Frei Gaspar da Cruz had given a complete description of how to make it? They who had produced Chinese laquer-ware and Chinese furniture in Lisbon almost as perfect as the originals which came from the Orient.

Perhaps it was cheaper for them to import it than to produce it. And because it was easy for them to acquire they went on developing their techniques for producing high quality faience. At the end of the 16th century, Portuguese faience was the best of its kind due to the perfection and excellent quality of the pieces with designs inspired by the Oriental ceramics brought to Lisbon on Portuguese ships.

While China was developing and perfecting porcelain and diversifying the range of models and designs, Portugal was developing faience and "azulejos" to the extent that in the 19th century Portugal was, according to some writers, a "Country dressed in azulejos".

The meeting of Portuguese and Chinese culture, the exchange of products, the discovery of different values, the different lights in which the world and life were regarded, changed some aspects of the European and Asian continents.

The exchange of ceramics which is nowadays promoted by business, fairs, exhibitions, visits from artists and an understanding of new tendencies in terms of materials, techniques and designs will further the friendship and mutual understanding between these two peoples.

The Leal Senado is hoping to promote contact between China and Portugal by holding these exhibitions and, like so many times in the past, it is Macau which is the contact point between the two countries,

BIBLIOGRAPHY

•Boulay, Anthony du: Chinese Porcelain, London, ed. Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1967.

•Brown, Roxana M.: The Ceramics of South-East Asia, Selangor, Malaysia, ed. Oxford Univ. Press, 1977.

•Bushell, Stephen W: Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Selangor, Malaysia, Oxford Univ. Press. 1977.

•Capon, Edmund: Art and Archaeology in China, Australia, Macmillan Company, 1977.

• Enciclopédia Luso-Brasileira de Cultufa, Lisbon, ed. Verbo.

•França, José Augusto: A Arte em Portugal no Seculo XIX, vol II, Lisbon, ed. Libraria Bertrand.

A Arte Portuguesa de Oitocentos, Lisbon, ed. ICALP.

•Mauss, Marcel: Manuel d'Etnographie, Paris, ed. Payot.

•Morin, Edgar: O Homem e a Morte, Lisbon, ed. Publicações Europa-America.

•Munsterberg, Hugo: The Arts of China, Tokyo, ed. Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1972.

•Portuguese Institute of Archaeology, History and Ethnography: A Arte Popular, 2nd edition, Oporto, ed. Portucalense Editora, 1959.

•Titiev, Misha: Introducão a Antropologia Cultural, Lisbon, ed. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation

•Treitsman, Judith: The Pre-History of China, Great Britain, ed. David and Charles, 1972.

•Yap Yong and Cotterell, Arthur: Chinese Civilization, London, ed. Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1977.

NOTES

(1) - Stephen Bushell: Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, Selangor, Malaysia. ed. Oxford Univ. Press, 1977, p. XII.

(2) - Idem, p. XIV.

(3) -Freire de Oliveira: "Elementos para a História do Município de Lisboa" 1st Part, Vol 9, p. 249 in José Queirós: Cerâmica Portuguese, vol 2, 2nd edition, ed. José Ribeiro, Aveiro.

* Anthropologist; researcher for the Luís Camões Museum.

start p. 83

end p.