One September evening in 1989, the artist Bartolomeu agreed to answer some questions about his life and work. He had arrived in Macau just a few days before on his first visit to the territory. An exhibition of around fifty of his engravings were on display in the gallery of the Leal Senado (City Council), the focus of great interest within the Portuguese community and of frank admiration from Chinese artists and art-lovers.

A few days previously, the Academy of Visual Arts had been officially opened. On the next day, once the red scraps of paper left over from the firecrackers had been swept away, Bartolomeu rolled up his sleeves, tied an enormous black apron round his waist and launched into what was probably Macau's first ever workshop in copper-plate engraving. Twenty two Chinese and Portuguese students took part in the classes.

Since this first visit, Bartolomeu has returned to Macau twice to continue his work of teaching engraving in the Academy. The studio is now excellently equipped and has a dedicated number of students who use it every day. The people of Macau have been able to visit view exhibitions of their work and a third is due to be held in London and Lisbon.

Interviewing Bartolomeu dos Santos is a delight: he is a great conversationalist and in addition to discussing any questions he pours forth analogies and asides. He is an endless source of stories about engraving, Portugal, books, the cinema, history and travel, to which he introduces his own shades of contrast and mysterious coincidences.

Few artists that I know of can provide so many clues as to the origins of their work. Bartolomeu will remember how a certain idea came to mind, how it developed and blended with other ideas through simple observation, reading, or from distant memories. Once he finishes his explanation he invariably says something like "But I shouldn't be talking about these things. The work should speak for itself." And speak it does... even for somebody who has never been to Lisbon or read Borges and Pessoa. All that's needed is a little admiration for the mysteries around us.

The following article consists of excerpts from the conversation Bartolomeu had with Luís Sá Cunha and myself.

Nuno Barreto

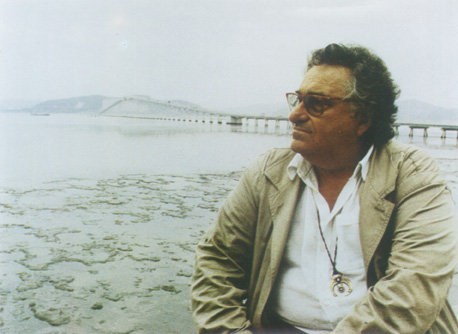

Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos was born in Lisbon in 1931.

He was able to travel from an early age throughout Portugal and abroad in the company of his grandfather Reynaldo dos Santos, one of the most outstanding Portuguese art historians.

By 1961 he had gone to work in London as a lecturer in the Slade School of Fine Art where he had studied print-making with Anthony Gross. He is now head of the same department. Since 1951, he has shown his work in over one hundred and thirty joint exhibitions across the world and in dozens of solo shows. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation's Modem Art Centre organised a major retrospective of his work in October and November 1989.

Photo by Nuno Barreto

Photo by Nuno Barreto

His work is included in some of the world's most famous public and private collections, such as the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Albertina Gallery in Vienna, the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Chicago Art Institute, the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation's Modem Art Centre in Lisbon.

Bartolomeu often visits Portugal where he has a house in Sintra.

At present, he is working on two marble panels engraved with acid which will be used to decorate an underground station in Lisbon.

His representative in Portugal is Galeria 111 in Lisbon.

Nuno Barreto

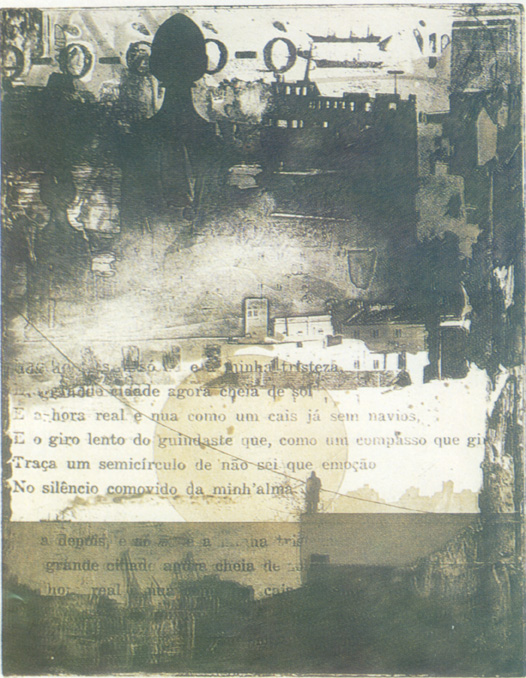

“Ode Marítima VI”, Bartolomen Cid dos Santos, 1988

“Ode Marítima VI”, Bartolomen Cid dos Santos, 1988

You have been living in England for over thirty years and yet your work still reflects strong links with Portugal, not only in its direct literary or geographical references, but also particularly through the emotional atmosphere you convey.

Does this reliance on Portugal have anything to do with a kind of self-defence, a need to maintain your own identity in the fogs of London, with its horizons of red brick and chimneys?

Bartolomeu dos Santos Living in London has given me a view of Portugal which I might not have if I lived there. I lived in Portugal until 1956 when I left to go and study in the Slade School. Long before this trip to England, I had already travelled to many countries throughout Europe with my grandfather Reynaldo dos Santos. I was able to see many things and to find out about all kinds of people. That's why, even before I left for England, I already had enough knowledge to develop a different view of my country from what I would have had if I'd never been out of it. Of course, this view, the ability to compare, is reflected in my work but it is not intended as a way of keeping hold of my identity.

Nuno Barreto

You have mentioned influences and critical distance. But there are also feelings and a sense of nostalgia. If we take a look at the exhibition you are holding in Macau, there are six works in the series "Ode Marítima": one called "On the beach", a Portuguese beach; "Nocturne" which is also in Portugal; "Seven figures waiting" in Lisbon; a "Return home" and a "Farewell" on another beach which is possibly in Portugal too.

Luís Sá Cunha

If you don't mind, I would like to add something to what Nuno has been saying: this series of six works seems to reveal something of the Portuguese collective subconscious which I would tend to associate with the following words: ship or boat, pier or beach, sea, departure, distance, waiting, demand, world, cartography, night, omen, discovery, return, dusk, secret, mystery. This is deeply connected with the animus (typical of Fernando Pessoa and the Portuguese), travelling and nostalgia for travelling implies an unexpressed desire to encounter mystery or a secret, and the environment of revelations themselves, the frontier which lies between day and night and vice versa.

It has already been said that Portugal is a twilight country, the best setting for feeling the twilight is on the beach.

"Girl in studio", 1956 (Bartolomeu's first print)

"Girl in studio", 1956 (Bartolomeu's first print)

BS

They include Portuguese place names, they are based on Portuguese landscapes but in fact they are not Portuguese landscapes. This is the case of the six prints for "Ode Marítima". I read the poems in 1951 when I bought the works of Alvaro de Campos in Tavira. Strangely enough, Alvaro de Campos was 'born' in Tavira. Just as "Ode Marítima" appears to be about boats and the sea and yet isn't, my works are not what they seem to portray. "Ode Marítima" is one of our century's greatest meta-physical poems and since the time I first read it I have always wanted to use it as the starting point for a series of works. It took me many years to achieve this. The other engravings you mention are of beaches and horizons. They are really asking questions about what can't be seen. The "Seven figures waiting" are not in Lisbon, they're waiting just anywhere... but they're not waiting for Dom Sebastião*.

NB

But waiting is a very Portuguese thing, whether it's waiting for Dom Sebastião or anything else.

BS

Yes, but in my case it isn't. It involves a search, trying to resolve an enigma which we know exists but can't really identify. There is a poem by Alvaro de Campos which begins: "E o explendor dos mapas, caminho abstracto para a imaginação concreta" and which ends with "O enigma visível do tempo, o nada vivo em que estamos!' ('The splendour of maps, an abstract path to concrete imagination... the visible enigma of time, the live nothingness in which we find ourselves') which, in a way, I associate with my pictures. But there is still no Dom Sebastião. For me, this figure that we turned into a myth to justify our frustrations is a negative image. Just because many of my pictures invite questions does not mean that they are negative. Quite the opposite. I think I now have a viewpoint, I can read, I can see my past work better. The work I am doing just now is guided by intuition, a kind of lighthouse which leads to the creation of the images. Years later, I can look at these images with the ease of somebody who is looking at work done by another person. I have an understanding which I didn't have when I was producing them.

NB

Anyway, isn't it because you are living abroad that you feel these emotions which are so Portuguese? If you lived in Portugal they may not have come out so strongly...

"Distasters of War", Goya

"Distasters of War", Goya

BS

No, I may not have had them. If I had stayed in Portugal my work would have followed a different path, certainly spiritually. But in Portugal there are many artists who are afraid to look around them and turn this experience into a mirror on the world which surrounds them. There is a fear of not being à la page, which is a pathetic state of cultural provincialism. Metaphorically speaking, people are painting Rauchenbergs in Campo de Ourique and Bacons in Reboleira. In fact it's strange that most Portuguese artists who live abroad use proportionately more Portuguese subjects than those who stay there. I don't mean to defend any kind of cultural parochialism, however, or even 'Portuguese' art. We should be aware of the world around us without ignoring our cultural roots. I think this is very important. I hardly need to say that our Spanish neighbours have the confidence which is so often lacking in us.

LSC

I think we are moving towards Almada's idea that an artists cannot live without his fatherland, I discovered this when I was abroad. Some cultural roots cannot be rejected, they weave their way into our lives through circumstance and the artist's unique tradition. Thus, the universal can be achieved on an individual level. The point of departure could be a beach, for instance.

"Seven Figures Waiting", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

"Seven Figures Waiting", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

BS

That's exactly it. This is a mythical beach, a metaphor. I am not only interested in the visual arts. I'm drawn by any creative form. Most of my books are not about art. They're books on history, travel books, fiction, poetry. My work is inspired by many sources including literature, music and films. There is no artist who has not been influenced by another artist and if an artist does deny external influences he is not being honest. Strangely enough, the creative spirits who have influenced my work during the last few years have not been artists. The poetry of Alvaro de Campos has had a tremendous influence on my work over the last ten years, as have Tarkovsky's films, Schubert's music and the works of Borges. All of their work involves an element of space, time and mystery which I identify with myself.

NB

You said just now that all artists are influenced and then you gave some names, all literary figures, a film director, a composer, who have contributed to your artistic character and your position amongst the arts. Would you care to mention two or three names of artists who have contributed to the way you express yourself through art?

BS

There is a huge number of artists in whom I am interested, including Mannerist painters. Some of my prints from eight years ago reflect this interest. At present, I am interested in some seventeenth century Spanish paintings, for instance Pereda and Valdez Leal's painting "Vanitas". Once again, these are subjects which deal with the passing of time. Caspar David Freidrich portrays figures, always with their backs turned to the spectator, watching over immense spaces. But these names give the impression that I am always looking back in time, which is not true. Many of my prints are based on photo collages made from photos which I take myself. On of the artists of our times who I particularly admire is Rauchenberg but in fact the first artists who influenced my work while I was still young and studying in the School of Fine Arts were the Italian metaphorical painters, Chirico, Morandi and Campigli. The first painting I produced when I started studying at the School of Fine Arts was a copy of a plaster model of, I think Antinous. In the background I painted a Chirico-inspired landscape with some arches and shadows. My teacher admonished me, saying that I was there to study modern art... this was in around 1950. You can see in my prints how still lifes with bottles and other objects turn up from time to time. When I'm not sure what I want to do, I do a still life. They evoke time and this gives me a feeling of restfulness.

NB

In ancient times, engraving was closely linked to books through illustrations, maps and the cover material. Many of your works introduce literary texts which seemed to be inspired by reading. When you were on the boat coming to Macau you were already asking when you would be able to visit the antiquarian book shops in the city! Tell me, are books very important for you?

BS

Yes, they are. Books are the labyrinth of understanding. First of all, when you have a library you have to know how to use it. Borges has a story in which the library is presented as a labyrinth, an enigma in which the words in the books are turned upside down. I don't want to go into it in detail but I am fascinated by the idea of the library as a form of universal knowledge. For Borges, the library is a metaphor for our knowledge or lack of knowledge about the world. I was born into a world of books. My grandfather had a library which covered Art, Literature and History. New books arrived every week! I grew up with this library and when I was sixteen, my grandfather asked me to put it all in order. I spent six months seated on a set of steps putting the books in order and as I didn't know any system for cataloguing books, I had to invent one. I read a huge amount of books, set the library to rights... and failed that year at school. But what I did gain was a passion for books. One of my uncles, Ernesto de Vilhena, had a wonderful library and my father's house had three floors just for books, something getting on for a Borges style labyrinth. Even now, more and more books appear... it's like being surrounded by friends.

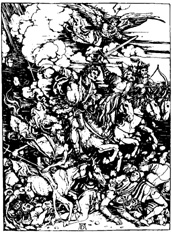

"The Four Knights of the Apocalypse", Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), 1498

"The Four Knights of the Apocalypse", Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), 1498

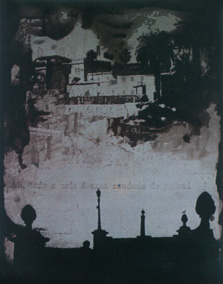

Engraving of the title page of Crónica do Condestável

Engraving of the title page of Crónica do Condestável

LSC

In fact, I can't think of anything other than books which offer such a perfect symbolic representation of Man's work and his dedication to culture. The words contain the spirit of man, the illustrations art, the printing and binding specific techniques. But most of all, the book is a product of printing which, since its earliest stages, has been linked to engraving and engravers. Don't you think that your love of books and contact with them may have been an early influence on your choice as a printmaker?

A NEW WAY OF SEEING

BS

No, I became a printmaker by accident. Before I went to the College of Fine Arts, I had begun to draw, especially landscapes and scenes in Lisbon. I would sometimes produce drawings which made a social, or rather political statement, something that occasionally surfaces in my work. I still have drawings I did when I was seventeen years old which are accompanied by a text. I went to the College of Fine Arts to study sculpture but in the following year I changed to painting. Before enrolling in the college, I had wanted to be an architect but I had never been very good with numbers and so I changed my mind. After studying in the college for four years, the atmosphere in Portugal was so bad and so oppressive that I decided to go abroad. I went to the Slade School where I spent the first three months completely lost. The attitude towards work in the Slade, the British way of thinking and behaving were completely different from what I had experienced in Lisbon and in fact it took me three months to understand this new world. In Lisbon there was a lot of talk and little thought and what thinking did go on was be-hind closed doors. In England I found a world of reserved people, artists with a tremendous capacity for synthesising and observing which was reflected in the kinds of drawings and paintings they produced. Moreover, I should say, in the Slade School there had been a long tradition of looking at the object. During this period, in the Lisbon College of Fine Arts we were trying to escape from the academicism which was overwhelming us by painting Modiglianis. In Britain I met artists and students who drew with tremendous precision and observed with a care that I was not used to. I tried to copy them but with no success. In the Slade all the students have a tutor, a teacher or an artist who is directly responsible for a certain student. My tutor was an artist called William Townsend. He was a man with exceptional perceptiveness and powers of observation where his students' work was concerned. After he had known me for three months, he looked at my work, which was all black and said: "You should do etching. I will take you to Anthony Cross who is a European". Anthony Cross looked like a French peasant with his moustache, shirt and waistcoat but no jacket, and cord trousers. That was the day I met the teacher who would introduce me to engraving. Without his teaching, I would not be what I am today.

"Ode Marítima I", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

"Ode Marítima I", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

LSC

Can you tell us about how you developed from being a student to being a teacher at the Slade School?

BS

I spent two years in England and then I returned to Portugal. My father gave me the kind of assistance that not everybody receives: he gave me a studio which had been designed by an architect. I was married and already had a daughter but even after three years I had still not managed to settle back into the Portuguese way of life. Those two years in England had made me look at things in a different way and I couldn't go back. I spoke another language. My failure to adapt when I returned to Portugal is something that I see happening to a lot of my foreign students. If they spend a year outside their country, then there's no problem, but if they study for two years, or if at the end of one year they ask to stay on for another year I know that many of them are going to ask if there is any way they can stay on in Britain. This is because they have become used to another system. It might be better, it might worse but it's the system they're used to and which, for all its defects, is a good one for working in. After three years in Portugal with scanty information in the newspapers and a lack of freedom of expression, pompous people everywhere and peasants on every corner (I had one on my doorstep who never found what he should have) I said to myself: "I'm off!" and I wrote to the Slade asking them to accept me as a student again. When he received the letter, Anthony Cross read it and said "We have two teaching days free in Printing" and wrote asking me if I wanted to take the post. I replied immediately "Yes, thank you". And so I went to England to teach and work on printmaking. I left my flat, sold the car and lent the studio which I have never used since. I started out in a little room with second hand furniture. At thirty, here I was starting from nothing but I never looked back. Sometimes people in Britain ask me why I don't have a British passport but I always reply that it's because I am Portuguese. Even though my way of thinking has changed over these years, I still behave like a Portuguese. I use my arms and hands to emphasise what I am saying which is a very Latin thing to do, I talk more loudly and get more excited... I sometimes ask myself where I belong, with part of myself in Portugal and part in Britain. It is a dichotomy which is reflected in my half expressionist, half classical work.

BORGES, ALVARO DE CAMPOS, GOYA AND BUÑUEL

NB

When I first saw your prints, you were deep in the labyrinth. It was 1960 something, I think.

BS

In the late sixties and early seventies.

NB

Those were some labyrinths! There was one at least which looked like a landscape of London but from close up you could see it was a labyrinth. How did you find the labyrinth?

BS

I can tell you. I went to America to teach, to give a printing workshop in the summer of 1969. I was in the University of Wisconsin, in Madison where Jorge de Sena was. We used to sit out on the verandah having long conversations in the warm evenings. But to get back to the labyrinths: before leaving for America, Paula Rego told me: "You should read Jorge Luis Borges, I'm sure you'll like him". Along with the labyrinths there was a film which was also behind this which I saw recently and found very dated: Kubrik's "2001". I had seen the film in London before leaving for the States. One afternoon in Madison I was looking at the window display in the university bookshop when I saw Borges' two books Labirintos and Ficciones. I remembered Paula's recommendation and decided to go in and buy them. The combination of "2001" and Borges' work is behind my labyrinths. When I returned to England I picked up a print which I had left half-finished and worked on it. The result was a complete departure from my previous work. I divide my work into before and after the labyrinths. There are certain points when everything in the artist is ready to break away from the previous work and to develop in new directions without the artist even being aware of this. It is at these times that an overheard word, a film, a sound, a book, a casual conversation, a picture seen years ago but forgotten, can be the cause of this change. The same thing happened to me with Alvaro de Campos' "Ode Marítima". I was in Tavira in 1951, I think, doing my military service. It was a fairly quiet experience as the wars in Africa had still not begun. I found the complete works of Alvaro de Campos in a little bookshop which still exists. From the very day when I read "Ode Marítima" I have always wanted to do a series based on it, not illustrations but works based on the poems. In the end it took me twenty five years from my first reading to produce an initial series and this only happened because one day, in the fair at Sintra, I bought a postcard with a picture of a ship and on the other side a message written from São Vicente in Cape Verde in the twenties. The combination of time, distance, the image and the anonymity of it all culminated in the six large prints entitled "Ode Marítima" which I produced recently. It just so happened that all these prints which use Pessoa as their theme or which show the poet himself were presented to the public during that period of euphoria about Pessoa, which has now begun to die down. It was pure coincidence.

"Nocturne", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

LSC

You spoke of labyrinths as a frontier in your artistic development and you have discussed the series inspired by Pessoa's "Ode Marítima". Do you want to talk about any other influences, other times?

BS

There is another series of prints in black and white which portrays bishops and petrified figures. They go from '58 to '63. When I was studying at the Slade I saw one of Buñuel's films which made a great impression on me. Usually this film is attributed to Dali because he is attributed with everything! In fact, Dali was only responsible for one scene. The film is called "The Golden Age" and has a famous scene involving bishops and a skeleton on the rocks beside the sea. I have never been able to shake off this image. Some years later this image began to show through in the prints I was making. Another experience which also left a deep impression on my work was an experience which I shall never forget: seeing King Henrique IV of Castile exhumed in the Convent of Guadalupe. It's a long fascinating story how his coffin was found. We know that he and the queen (Joana of Castile, the Portuguese princess who was the daughter of Dom Duarte and Dona Leonor) had been buried in two great bronze tombs. These disappeared and it was thought that they had been melted down. The bodies were found behind the altar in two wooden coffins in a crypt. I was in Madrid with my grandfather who was a member of a committee which was formed at the time to officially open the tombs. I went as a hanger-on. The committee also included Professor Marañon, a doctor and historian, and Gomez Moreno, a small figure dressed in black with a white beard who was director of the National Monuments of Spain. The ceremony took place at night in the great church illuminated with powerful floodlights. Bach was played on the organ. Before the ceremony we visited the sacristy where we admired the Zurbarans. The king in his riding boots and wrapped in a gorgeous velvet cape, was naturally mummified. It was a really Buñuel-like scene. Because they couldn't get him out of the crypt, they handed the head to me and I put it on the altar. Apart from the official photographs, I took two photos with a simple camera I had taken with me. This experience is still very fresh in my mind. The series of bishops grew out my association of this experience with Buñuel's films and the "Vanitas" I mentioned before. Stylistically, although they are reminiscent of Chirico, they also owe a lot to Goya's engravings. I know that now, but at the time I didn't. Once, while I was doing that series, William Townsend was with me at an opening in the Leicester Galleries of an exhibition by a neo-Romantic artist who was very popular at the time but has now virtually been forgotten. William Townsend introduced me to Francis Bacon saying "here's a Portuguese artist who also does Popes". At the time Bacon was painting, or had just finished painting, his series on Pope Innocent as painted by Velasquez. I immediately corrected his introduction by confirming that I was Portuguese but that I didn't paint Popes, but rather engraved them in very small sizes...

I'm just remembering another old series. When I arrived in England, the city was black. You also knew London when it was black, didn't you Nuno? Now they're washing it. It's a new city. But that black was quite nice, the way it contrasted with the white where the Victorian soot had not got in. When I arrived in London in 1956, however, I saw those lucid grey skies for the first time, the complete opposite of the sky I knew in Portugal. Everything stuck into the sky: the chimneys, the railway signals, the steam trains puffing out smoke. At night time the city was like a poem by William Blake. At the time, London always had a nocturnal air. I did a lot of prints with chimneys and signals.

BOATS IN THE BACKGROUND

NB

You have produced around four hundred and fifty prints to date and a lot of them have boats. Boats in the distance, boats in storms, shipwrecks, schooners and steam boats, nautical charts old and new, and even people saying their farewells or waiting for the steam boat to arrive.

BS

They're all boats. The people are still waiting... and the country...

NB

Where do these boats come from? Are they from your memories of Portugal, from the docks in London, the books you have read, or are they from voyages that you would one day like to go on?

"Four Bishops", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1962

BS

No, they don't come from me. Don't ask me why because I don't know the reason but I've been fascinated by boats since I was a child. I remember when I was around five or six years old going to see the boats in the docks with my great uncle and my godfather, João de Vilhena, an eccentric who collected the bottle label and books covers which he tore off and then flattened out on pieces of card like butterflies. I remember seeing a boat in the Rocha docks during the sailors' revolution which was completely wrecked.

LSC

Throughout time, the boat appears as a symbol in every tradition. What does it mean to you?

BS

I don't know. I'd like to know. My house in Sintra is full of boats. Models of old sailing boats and steamships; books about boats as well as travel books and maps. Here in Macau I visited the Maritime Museum and found it fascinating. These are autonomous inner worlds which have their own lives. A boat has its own character, its own personality. For me it's as if it were alive. Maybe that's why I use it as a kind of metaphor. It can be taken as a complete unit in a huge expanse of ocean.

"Head of Henry IV of Castile", photo by Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos

NB

Bartolomeu, almost every Portuguese artist has produced the occasional engraving. But there are few engravers of any stature who are working on a continual basis. Would you like to mention a few of the ones you think are more interesting?

BS

Portuguese?

NB

Portuguese

LSC

I would like to suggest that you include some of the history of engraving in Portugal because there has been nothing written on the subject so far.

BS

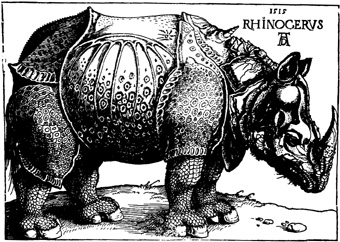

Let's start at the beginning. I don't know why but we have never been a country of engravers, there have been no Mategnas nor Dürers, no Piranesis nor Goyas. If my memory serves me, the first engravings produced in the fifteenth century were done in wood, depicting the "Vita Christi". Engraving in the sixteenth century focussed mostly on books but they were mostly routine pieces. I know little about the seventeenth century except that there is an engraving by Josefa de Obidos for the Statutes of the University of Coimbra. The eighteenth century was more promising with the appearance of Vieira Lusitano and Carneiro da Silva, the founder of the King's Engraving Studio. I have Carneiro's engraving manual, a work by Abraham Bosse which was published in Paris. It is full of handwritten notes and contains his measurements for the printing press he commissioned, which is now held in the College of Fine Arts. It is a fascinating book. I keep it in my drawer at the Slade and refer to it often. It gives me a lot of pleasure to be using a book which belonged to such a great Portuguese engraver. Sequeira must have been the first Portuguese artist to experiment with what was then the newly-created art of lithography. The nineteenth century was also a vacuum for engravers. It's strange when we think that Rodrigo and Brandão, the two Portuguese factors posted in Antwerp, received around a hundred engravings from their friend Dürer (according to his own diaries) which certainly ended up in Portugal.

LSC

The rhinoceros one, which everybody knows...

BS

The rhinoceros, which must have been taken from a drawing by Dürer. It we read his diaries he talks often of Portugal, or rather the Portuguese. There are two great artists' diaries from the sixteenth century: one written by Cellini, the diary of an extrovert who was completely in love with himself. The other is a travel journal kept by Dürer when he visited Holland. It is a mixture of a story book and a report. Whenever he gave or received a present (which happened frequently) he kept a note of its value. He gave a huge number of engravings and drawings to friends. The factors sent him parrots, ostrich eggs and other exotic things and he returned the compliment by giving his drawings. The presence of northern engraving in Portugal did not affect in any way the development of our own art even though four bassreliefs in the church of Santa Cruz in Coimbra were taken from engravings by Dürer. This shows that his engravings were known in Portugal at the time.

"Rhinocerus", Albrecht Dürer, engraving 1515

It is not until the twentieth century that we find the first great Portuguese engraver: Sousa Lopes. He has now been almost completely forgotten by the public and ignored by the critics. Sousa Lopes was a naturalist painter and he produced some very fine work for the Military Museum.

NB

He did etchings of war scenes didn't he?

BS

Yes, he did a series if engravings of scenes of the First World War which are extremely powerful. Out of the many British artists of the period who portrayed scenes of war, there isn't a single one who compares with Sousa Lopes.

NB

He seems to have sprung up from nowhere. I mean, who did he study engraving with?

BS

He must have learnt in France but I don't know with whom. It's time we found out. Diogo de Macedo was in Paris for around twenty years. He was friends with Modigliani and many other artists. He was a great storyteller and he also produced several quality engravings. The same thing applies to Francisco Franco, the sculptor who produced some wood engravings and etchings in Paris. Also Milly Possoz who also did some etchings in Paris on the style of Marie Laurencin. There were a few more but there isn't time to talk about them all. In 1956, I think, the Engraver's Cooperative was created. I was in England. When I returned it was already working and I joined. There were already several artists working in the Cooperative. We were starting from nothing.

NB

Like Pomar

BS

Pomar, Vieira Santos and, in fact one of the real driving forces behind the Cooperative, Sá Nogueira...

NB

Alice Jorge...

BS

Alice Jorge, Jorge Barradas amongst others. I mean that it was this group which launched contemporary engraving in Portugal. They learned at the expense of books and trying new things out.

NB

There was hardly any engraving in Portugal.

BS

Apart from the exceptions I have mentioned, no there wasn't. Just as there wasn't any equipment or the equipment that did exist was useless. I remember that when I was in the College of Fine Arts I saw the huge eighteenth century printing press which I've just talked about along with another two presses, one of them for wood engravings which nobody knew how to use. It's true that there are a lot of engravers working in Portugal now and some of them are very good.

NB

Portugal used to have an institution just for engraving documents, paper money...

LSC

The Royal Press, which had the Royal Playing Card Factory working alongside it.

BS

Yes, it did exist. It must have been where the Mint now stands. I'm not sure, but it wasn't really connected to engraving as an art form. As for the playing card factory you mentioned, I think there was a playing card factory founded during the time of Pombal.

In fact it was the Royal Engraving Studio founded during the reign of Dom Joao VI and directed by Carneiro da Silva which was the forerunner of artistic engraving in Portugal. I think it was located in the Convent of Sao Francisco in Lisbon where the College of Fine Art now stands. I remember when I was a student there that I went into a small room and found hundreds of copper plates piled up. This was the core of the Royal Engraving Studio's material! Now I think they have been included in a national collection of chalcography which is one of those cultural organisations which come onto the scene still-born in Portugal.

NB

Would you like to talk about some contemporary engravers?

BS

No, I don't think I should name names but I can say that nowadays there are some very good engravers working in Portugal using all kinds of techniques and, as in all fields, there are some who are more interesting than others.

LSC

Do you think Portugal is behind the times in this field?

BS

No. Portugal already has its own engraving studios and some artists even have their own presses. But obviously, as we've already said, the major force behind this was engraving itself.

LSC

And now there is a studio in Macau.

BS

Yes, and I would say that it is equal to any good engraving studio in Europe. The interest in engraving apparent in Macau today is the same as there has been in Portugal over recent years although on a smaller scale. Today, many of our engravers are known throughout the world and foreign artists have started to go to Portugal to work.

After the Storm, Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1983

LSC

Which didn't happen before...

BS

And there are a lot of Portuguese who have studied engraving in London, Paris or the United States. One of them who, as far as I know, never worked outside Portugal was João Hogan, a cabinetmaker by profession, a fair drinker and a great engraver as well as painter.

FROM WOOD TO LASER

LSC

Could you tell us something about the future of engraving, taking into account the introduction of photography, the progress which has been made in printing and the new materials available. What are the implications of all these techniques on engraving and printing?

BS

It's a strange thing that all the engraving techniques used by artists up to the present were not in fact invented by engravers but rather by printing technicians who were trying to improve reproduction methods and the speed of printing. We should also recognise that in the early stages of printing there was little difference between the craftsman and the artist. The first engravings which appeared were done with wood blocks. These were the first mass-produced reproductions to be made and thousands of proofs could be run off a single block. The subjects were usually religious, for instance pictures of saints. There were also political themes at times, however, such as attacks on the Pope during the Reformation. Wood block engravings were easy to print but they did not allow for great detail. The burin, another technique, was used by gold and silversmiths to decorate their work with engraved designs. Mantegna in Italy and Dürer in Germany were the first to adapt this technique to the art of engraving. Dürer was also one of the first artist to use etching which was a technique originally used by armourers for engraving designs on the suits of armour they made. They put ink over the designs and took paper proofs to include in catalogues which they could show to their customers. It was only a short step from this to the technique being use by artists. Etching and the burin were excellent techniques for copying pictures. This was how many of the great Renaissance artist came to be known in other countries. This also marked the beginning of engraving as a means of reproduction as opposed to creating works of art. This use of engraving disappeared when Photography was invented. If you look at a copy of the Illustrated London News from the nineteenth century, you can see it is completely illustrated with engravings done from photographs. When photolithography was invented, there was no more work for copiers and the profession just died out. Photolithography was the development of lithography on stone which was invented in the early nineteenth century by Sennefelder and allowed works of art to be copied quickly. Towards the end of his life, Goya pioneered its use as a form of art. Nowadays, all of these techniques and others which I haven't mentioned are only kept alive so long as artists use them. Screen printing is another technique which artist have adapted for their own use. Photography too. Artist are even using xeroxes, lasers and faxes to make art. These new techniques are absorbed without the old one being dismissed.

"Sintra", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1988

NB

Can you tell us something about your studio, the space you use for working. Is it closed or open? Do people visit you there? Do you work when friends are around?

BS

I always worked in the Slade's teaching studio. I have never been able to go through whole days just teaching. My teaching methods are more empirical, in other words I give demonstrations, practical examples. This is how I actually managed to change the Slade studios into a huge engraving workshop where the teachers (seven of us) work alongside the students. I've got used to working like that, surrounded by people, and it doesn't disturb me at all. There are also people who go to visit studios and this can sometimes create certain problems but if we didn't have such a stable reputation then nobody would come to visit. If I want to work in peace, however, I can work in the studio at the weekend, which I often do. What we must understand is that for an art school to be alive, it has to be a place where communication can take place and where the only difference between the teachers and the students is that the former have been at it for longer.

"On the Beach", Bartolomeu Cid dos Santos, 1987

NB

So being with young people, students, is important, stimulating for you?

BS

Of course it is. It is fascinating to see the work of young artists coming to life before our eyes. And just as I criticise their work, they too criticise mine and I'm very grateful to them.

NB

And what now?

BS

I'm thinking of setting up a studio in Portugal. One of these days I'll retire from teaching in the Slade. Of course I'll not retire as an artist because artists never retire. But when I do leave the Slade I'll need somewhere to work. I know I could always carry on working in the Slade but it couldn't be forever because one must give way to younger people and not interfere with them. Whatever happens, whether it's in Britain or in Portugal or anywhere else, I will still carry on doing engravings and also painting as my engravings seem to be heading that way at the moment.

start p. 176

end p.